As Early As 1946, a Year Before Independence, the Government Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernization This Ispublic Health: Acanadianhistory

Table of Contents Endnotes – Glossary Credits Profiles Contact CPHA 1920This is Public Health: A Canadian1929 History CHAPTER 3 printable version of this chapter Modernization and Growth . 3 .1 Maternal and Child Health . 3 .2 Public Health Nurses . 3 .4 Full-Time Health Units . 3 .5 Services for Indigenous Communities . 3 .7 Venereal Disease . 3 .8 Charitable Organizations . 3 .9 Lapses in Oversight: Smallpox and Typhoid . 3 .11 Toronto’s School of Hygiene and Connaught Laboratories . 3 .14 Poliomyelitis . 3 .15 Depression and the End of Expansion . 3 .16 Table of Contents Endnotes – Glossary Credits Profiles Contact CPHA 1920This is Public Health: A Canadian1929 History 3.1 CHAPTER 3 Dominion Council of Health Modernization The .Dominion .Council .of .Health . was .chaired .by .the .federal .Deputy . Minister .of .Health .and .made .up .of . and Growth the .chief .provincial .officers .of .health . and .representatives .of .urban .and . A .new .public .health .order .emerged .in .the .aftermath .of .World .War .I, .represented .at .the . rural .women, .labour, .agriculture .and . universities, .the .latter .representing . international .level .by .the .development .of .the .Health .Organization .of .the .League .of .Nations . academic .and .scientific .expertise .in . In .Canada, .this .new .order .was .symbolized .by .the .Dominion .Council .of .Health .(DCH), .which . medicine, .public .health .and .laboratory . was .created .to .develop .policies .and .advise .the .new .federal .Department .of .Health . .Initially, . research . .The .Council .provided .a . the .Department .was .primarily .focused .on .collecting .and .distributing .information, .with .some . twice-yearly .forum .to .openly .discuss, . lesser .effort .to .develop .federal .laboratory .research .capacity . compare .and .co-ordinate .strategies .on . the .major .public .health .concerns .of .the . -

The Spanish Flu and Canadian Influenza Vaccine Initiatives

DefiningMomentsCanada.ca THE SPANISH FLU AND CANADIAN INFLUENZA VACCINE INITIATIVES Christopher J. Rutty, Ph.D. significant but sometimes overlooked element in the history of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-19 A was the experimental production, distribution and wide use of influenza vaccines. Since the vaccines were based on an erroneous view that influenza was caused by a bacteria (the influenza virus would not be isolated until 1933) such vaccines were ineffective and thus of little importance to the course of the pandemic from a medical or public health perspective. However, the story of the vaccines produced to prevent pandemic influenza, particularly in Canada, reveals much about the application of uncertain knowledge in the face of an unprecedented public health emergency. It also reveals the changing state of Canadian biotechnology capacity at the end of World War I. Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories of the University of Toronto led the most significant initiative to produce an influenza vaccine.1 Connaught’s flu vaccine initiative coincided with a significant production effort by the Ontario Provincial Laboratories, along with various smaller scale and more local efforts, particularly in Kingston and Winnipeg.2 Canadian vaccine efforts were also linked to emergency vaccine preparation in New York City, Boston, and at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.3 Influenza vaccines were similarly prepared in other countries in the face of the global pandemic. In 1919, Dr. John G. FitzGerald, Director of Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories, began his summary of Connaught’s influenza vaccine work by observing: “almost coincident with the end of the war a great emergency arose in which the laboratories were provided with an opportunity of doing public service work of a national character.”4 Connaught had been established in May, 1914, as the Antitoxin Laboratory in the Department of Hygiene, 1 Online resources about the history of Connaught Laboratories include: http://connaught.research.utoronto.ca/history/; http:// thelegacyproject.ca 2 J.W.S. -

Correspondence, Research Notes and Papers, Articles

MS BANTING (FREDERICK GRANT, SIR) PAPERS COLL Papers 76 Chronology Correspondence, research notes and papers, articles, speeches, travel journals, drawings, and sketches, photographs, clippings, and other memorabilia, awards and prizes. Includes some papers from his widow Henrietta Banting (d. 1976). 1908-1976. Extent: 63 boxes (approx. 8 metres) Part of the collection was deposited in the Library in 1957 by the “Committee concerned with the Banting Memorabilia”, which had been set up after the death of Banting in 1941. These materials included papers from Banting’s office. At the same time the books found in his office (largely scientific and medical texts and journals) were also deposited in the University Library. These now form a separate collection in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. The remainder of the collection was bequeathed to the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library by Banting’s widow, Dr. Henrietta Banting, in 1976. This part of the collection included materials collected by Henrietta Banting for her projected biography of F.G. Banting, as well as correspondence and memorabilia relating to her won career. Researchers who wish to publish extensively from previously unpublished material from this collection should discuss the question of literary rights with: Mrs. Nancy Banting 12420 Blackstock Street Maple Ridge, British Columbia V2X 5N6 (1989) Indicates a letter of application addressed to the Director, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, is needed due to fragility of originals or confidential nature of documents. 1 MS BANTING (FREDERICK GRANT, SIR) PAPERS COLL Papers 76 Chronology 1891 FGB born in Alliston, Ont. To Margaret (Grant) and William Thompson Banting. -

Mvx List.Pdf

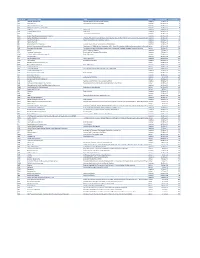

MVX_CODE manufacturer_name Notes status last updated date manufacturer_id AB Abbott Laboratories includes Ross Products Division, Solvay Inactive 16-Nov-17 1 ACA Acambis, Inc acquired by sanofi in sept 2008 Inactive 28-May-10 2 AD Adams Laboratories, Inc. Inactive 16-Nov-17 3 ALP Alpha Therapeutic Corporation Inactive 16-Nov-17 4 AR Armour part of CSL Inactive 28-May-10 5 AVB Aventis Behring L.L.C. part of CSL Inactive 28-May-10 6 AVI Aviron acquired by Medimmune Inactive 28-May-10 7 BA Baxter Healthcare Corporation-inactive Inactive 28-May-10 8 BAH Baxter Healthcare Corporation includes Hyland Immuno, Immuno International AG,and North American Vaccine, Inc./acquired somInactive 16-Nov-17 9 BAY Bayer Corporation Bayer Biologicals now owned by Talecris Inactive 28-May-10 10 BP Berna Products Inactive 28-May-10 11 BPC Berna Products Corporation includes Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute Berne Inactive 16-Nov-17 12 BTP Biotest Pharmaceuticals Corporation New owner of NABI HB as of December 2007, Does NOT replace NABI Biopharmaceuticals in this codActive 28-May-10 13 MIP Emergent BioSolutions Formerly Emergent BioDefense Operations Lansing and Michigan Biologic Products Institute Active 16-Nov-17 14 CSL bioCSL bioCSL a part of Seqirus Inactive 26-Sep-16 15 CNJ Cangene Corporation Purchased by Emergent Biosolutions Inactive 29-Apr-14 16 CMP Celltech Medeva Pharmaceuticals Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 17 CEN Centeon L.L.C. Inactive 28-May-10 18 CHI Chiron Corporation Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 19 CON Connaught acquired by Merieux Inactive 28-May-10 21 DVC DynPort Vaccine Company, LLC Active 28-May-10 22 EVN Evans Medical Limited Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 23 GEO GeoVax Labs, Inc. -

Chronological Introduction of Types of Vaccine Products That Are Still Licensed in the United States

Appendix 2.3 CHRONOLOGICAL INTRODUCTION OF TYPES OF VACCINE PRODUCTS THAT ARE STILL LICENSED IN THE UNITED STATES The year of introduction of each of 49 of the 51 shown in table 2.3B, American pharmaceutical com- types of vaccine prducts currently licensed in the panies were issued 37 (89 percent) of the original United States, alolng with the manufacturing estab- licenses for these 42 products. New or improved lishment with the oldest license still in effect for each types of products that are currently licensed have product, is shown in table 2.3 A.] For 42 (86 percent) been introduced at a fairly consistent rate of three to of these 49 products, the establishment that received seven products per each 5-year interval since 1940.2 the original product license still holds this license. As Ten of the currently licensed products were licensed before 1940. Table 2.3A—Chronological Introduction of Types of Vaccine Products Still Licensed in the United States Year Type of vaccine product Establishment with oldest product license still in effecta 1903 Dlphtherla antitoxin Massachusetts Public Health Biologic Laboratories (191 7) 1907 Tetanus antitoxin Parke. Davis and Company (191 5) 1914 Pertussis vaccine Lederle Laboratories Typhoid vaccine Massachusetts Public Health Biologic Laboratories (191 7) Rabies vaccine . Eli Lilly and Company* 1917 Cholera vaccine Eli Lilly and Company* 1926 Diphtheria toxoid Parke, Davis and Company (1927) 1933 Staphylococcus toxoid Lederle Laboratories* Tetanus toxoid Merck Sharp and Dohme 1941 Typhus vaccine Eli Lilly and Company 1942 Plague vaccine .., . Cutter Laboratories* Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever vaccine. Lederle Laboratories* 1945 InfIuenza virus vaccine Lederle Laboratories Merck Sharp and Dohme Parke, Davis and Company * 1946 Parke, Davis and Company ● 1947 Parke, Davis and Company (1949) 1948 Parke, Davis and Company (1952) Parke. -

Smallpox Vaccine and Vaccination in the Intensified Smallpox Eradication Programme

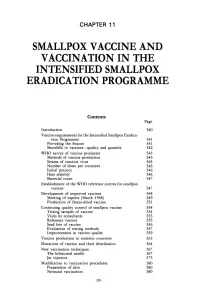

CHAPTER 11 SMALLPOX VACCINE AND VACCINATION IN THE INTENSIFIED SMALLPOX ERADICATION PROGRAMME Contents Page Introduction 540 Vaccine requirements for the Intensified Smallpox Eradica- tion Programme 541 Providing the finance 541 Shortfalls in vaccines-quality and quantity 542 WHO survey of vaccine producers 543 Methods of vaccine production 543 Strains of vaccinia virus 545 Number of doses per container 545 Initial potency 546 Heat stability 546 Bacterial count 547 Establishment of the WHO reference centres for smallpox vaccine 547 Development of improved vaccines 548 Meeting of experts (March 1968) 549 Production of freeze-dried vaccine 551 Continuing quality control of smallpox vaccine 554 Testing samples of vaccine 554 Visits by consultants 555 Reference vaccine 555 Seed lots of vaccine 556 Evaluation of testing methods 557 Improvements in vaccine quality 559 Vaccine production in endemic countries 563 Donations of vaccine and their distribution 564 New vaccination techniques 567 The bifurcated needle 567 Jet injectors 573 Modification to vaccination procedures 580 Preparation of skin 580 Neonatal vaccination 580 539 5 40 SMALLPOX AND ITS ERADICATION Page The search for new vaccines 580 Selection of vaccinia virus strains of low patho- genicity 581 Attenuated strains 583 Inactivated vaccines 587 Production of vaccine in eggs and tissue culture 588 Silicone ointment vaccine 590 Efficacy of vaccination 590 INTRODUCTION In May 1980 the Thirty-third World Health Assembly, after it had declared that Vaccination against smallpox had been smallpox had been eradicated throughout the practised in virtually every country of the world, recommended that smallpox vacci- world, and in many on a large scale, when the nation should be discontinued, except for in- Intensified Smallpox Eradication Programme vestigators at special risk . -

Fifty Years of Insulin

24 Ju1ie 1971 S.-A. MEDIESE TYDSKRIF 815 Fifty Years of Insulin Emaciation, weakness, coma and death. The VlctlffiS were of sugar and other carbohydrates. He would then inject the children. The outcome was always the same. Only deliberate extract into a second dog who had diabetes. On 30 July 1921 starvation could slow the lethal course of the disease. Banting performed the experiment that con.firmed the existence This is a picture of juvenile diabetes in 1921. In that year, of insulin. He removed the pancreas of the dog Marjorie and an obscure Canadian physician, Frederick Banting, made then kept her alive and active for 76 days with injections of an medical history when he discovered the hormone insulin and extract made from the pancreas glands of other animals. He later provided its ability to control diabetes. Insulin, of course, finally sacrificed her on 14 October to check for possible has since saved millions of lives throughout the world. The internal damage from the extract. He found no evidence of year 197 I is the 50th anniversary of Banting's historic discovery. injury. The story of insulin actually began on the night of 30 October An impaired ability to utilize carbohydrates is, of course, 1920. Young Dr Banting, then a demonstrator in physiology the basic problem in the disease. Juvenile diabetics, especially, at the University of Western Ontario, arose at two in the have a severe impairment. morning to jot down procedures for an experiment that would Because of limited laboratory facilities at Western Ontario, eventually reveal the life-saving hormone. -

The Birth of the Biotechnology Era: Penicillin in Australia, 1943-1980

MACQUARIE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF MANAGEMENT MGSM CASE STUDIES IN MANAGEMENT The birth of the biotechnology era: Penicillin in Australia, 1943-1980 John A. Mathews MGSM Case 2001-2 April 2001 Disclaimer MGSM Case Studies in Management are produced as a means of stimulating discussion amongst management scholars and students. The facts reported are meant for discussion only, and are not be interpreted as imputing any value judgments on management decisions and actions. Copyright © John A. Mathews Research Office Macquarie Graduate School of Management Macquarie University Sydney NSW 2109 Australia Tel 612 9850 9016 Fax 612 9850 9942 Email [email protected] URL http://www.gsm.mq.edu.au/research Director of Research Professor John A. Mathews Manager, Research Office Ms Kelly Callaghan ISSN 1445-3126 Printed copy 1445-3142 Online copy MGSM Case 2001-2 The birth of the biotechnology era: Penicillin in Australia 1944-1980 Dr John A. Mathews Professor of Management Director Research Macquarie Graduate School of Management Macquarie University Sydney NSW 2109 Australia Tel 61(0)2 9850 6082 Fax 61(0)2 9850 9942 Email [email protected] URL http://www.gsm.mq.edu.au/faculty/home/john.mathews ii Contents Abstract Acknowledgments 1. Introduction 2. What is penicillin? 3. The development of penicillin: an Australian success story 4. The wartime production of penicillin: the “second Manhattan project” 5. Australian involvement in wartime penicillin production: the Commonwealth Serum Laboratories 6. Postwar penicillin and antibiotic production industry in Australia 7. Rundown of the Australian penicillin industry 8. Paths not taken in the Australian penicillin industry 9. -

ADULT IMMUNIZATION a Report by the National

and Prevention (CDC! Atlanta GA 30333 Dear Colleague: Every year in the United States between 50,000 to 70,000 adults die of influenza, pneumococcal infections, and hepatitis B. The cost to society for these and other vaccine-preventable diseases of adults exceeds 10 billion dollars each year. In January 1994, the National Vaccine Advisory Committee (NVAC) adopted the report of its Adult Immunization Subcommittee. The report describes five major goals for adult immunization in the United States, and lists 18 recommendations and 72 strategies for achieving the recommended goals. The National Vaccine Program Office is consulting with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, the Food and Drug Administration, the Health Care Financing Administration, other relevant agencies, and private and voluntary organizations to identify steps each can take to implement the report's recommendations. Enclosed, for your information, is a copy of the report. A synopsis of the report prepared by Dr. David S. Fedson, Chair of the NVAC Subconunittee on Adult Immunization, was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in October 1994 (JAMA October 12, 1994; Vol 272, No. 14). If you have questions about the report, you may contact Chester Robinson at the National Vaccine Program Office, (301) 594-6350, or Joyce Goff at the National Imunization Program, (404) 639-8257. Sincerely yours, 0-< Q-Qk.Walter A. Orenstein. M.D. Director National Immunization Program Enclosure ADULT IMMUNIZATION A Report By -

Brief of Petitioner for Bruseeswitz V. Wyeth, Inc., 09-152

No. 09-152 IN THE Supreme Court of the United States ———— RUSSELL BRUESEWITZ AND ROBALEE BRUESEWITZ, PARENTS AND NATURAL GUARDIANS OF HANNAH BRUESEWITZ, A MINOR CHILD, AND IN THEIR OWN RIGHT, Petitioners, v. WYETH, INC. F/K/A WYETH LABORATORIES, WYETH- AYERST LABORATORIES, WYETH LEDERLE, WYETH LEDERLE VACCINES AND LEDERLE LABORATORIES, Respondent. ———— On Writ of Certiorari to the United States Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit ———— BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT ———— DANIEL J. THOMASCH KATHLEEN M. SULLIVAN RICHARD W. MARK Counsel of Record E. JOSHUA ROSENKRANZ FAITH E. GAY LAUREN J. ELLIOT SANFORD I. WEISBURST JOHN L. EWALD WILLIAM B. ADAMS ORRICK, HERRINGTON & QUINN EMANUEL URQUHART SUTCLIFFE LLP & SULLIVAN, LLP 51 W. 52nd Street 51 Madison Ave., 22nd Flr. New York, NY 10019 New York, NY 10010 (212) 506-5000 (212) 849-7000 kathleensullivan@ quinnemanuel.com Counsel for Respondent July 23, 2010 WILSON-EPES PRINTING CO., INC. – (202) 789-0096 – WASHINGTON, D. C. 20002 QUESTION PRESENTED Section 22(b)(1) of the National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act of 1986 provides: “No vaccine manufacturer shall be liable in a civil action for damages arising from a vaccine-related injury or death associated with the administration of a vaccine after October 1, 1988, if the injury or death resulted from side effects that were unavoidable even though the vaccine was properly prepared and was accompanied by proper directions and warnings.” 42 U.S.C. 300aa-22(b)(1). The question presented is: Does Section 22(b)(1) preempt vaccine design- defect claims categorically, or must a vaccine manufacturer also show, case by case, that the side effects at issue could not have been avoided by some differently designed vaccine? (i) ii RULE 29.6 STATEMENT Respondent Wyeth, Inc. -

Leone Farrell

Leone Farrell Research Scientist: Mass Production of Polio Vaccine The production of quantities of the polio vaccine was achieved through a process that became known throughout the world as the Toronto technique. he mystery lady of Connaught Laboratories, or so she seemed to me when I first began probing to find out more about her. Even her name had an air of Tmystery about it. I did know that she was a Canadian scientist who was an important player in the world conquest of the dread disease polio over half a century ago. Yet, no one seemed to know who she was outside of Connaught Labs, where she worked for over 35 years, and the broader community of scientists who knew about the disease. Certainly, she was not famous like hockey players are in Canada, but there is no question she should have been, given the lasting importance of her work. Curiously, there does not even seem to be a simple monument or plaque anywhere to commemorate her accomplish- ments. However, old Knox College, the neo-Gothic building she worked in on Spadina Avenue in Toronto, is miraculously still standing in the middle of a traffic circle north of College Street, and is a monument of sorts. The Toronto Academy of Medicine, I am told, plans to erect a commemorative plaque to Leone Farrell there. Poliomyelitis (or simply polio) is an infectious disease caused by any one of three distinct types of poliovirus. The virus enters the body through the mouth, multiplying in the gut and, if not stopped there or in the bloodstream, invades the central nervous system, targeting the delicate nerves of the spinal cord, disrupting communication between the brain and muscles, and often leading to varying degrees of paralysis and sometimes death. -

INDIANA LAW REVIEW [Vol

. Tort Liability for DPT Vaccine Injury and the Preemption Doctrine Infectious childhood diseases claimed thousands of lives annually in the United States before mass immunization brought the spread of communicable diseases under control. Today, vaccination of infants and young children is routine, and diseases such as pertussis, once a major cause of childhood mortality, are uncommon.' The development of vaccines to combat pertussis and other contagious diseases paralleled the growth of the administrative state during the 1930's and 1940's. The federal government, recognizing the national dimensions of disease control and the public health interest in safe and effective vaccines, implemented a regulatory scheme in 1944 which required licensure of all vaccine products and manufacturing facilities.^ Today, the Food and Drug Ad- ministration (FDA) is responsible for determining safety standards in the vaccine industry. The FDA licenses only one form of pertussis vaccine, which is administered routinely to young children as part of a three-in-one vac- cination program. The FDA-approved DPT vaccine combines three dif- ferent antigens to provide protection against diphtheria ("D"), pertussis CT"), and tetanus C*T"). Despite consistent FDA approval, DPT vaccine has become the subject of controversy in recent years due to increased public awareness of the possibility of serious adverse reactions linked to the pertussis component. Although alternative types of pertussis vaccine currently are available in other countries, manufacturers are not