Administration of Insulin Patents by the University of Toronto Maurice Cassier, Christiane Sinding

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernization This Ispublic Health: Acanadianhistory

Table of Contents Endnotes – Glossary Credits Profiles Contact CPHA 1920This is Public Health: A Canadian1929 History CHAPTER 3 printable version of this chapter Modernization and Growth . 3 .1 Maternal and Child Health . 3 .2 Public Health Nurses . 3 .4 Full-Time Health Units . 3 .5 Services for Indigenous Communities . 3 .7 Venereal Disease . 3 .8 Charitable Organizations . 3 .9 Lapses in Oversight: Smallpox and Typhoid . 3 .11 Toronto’s School of Hygiene and Connaught Laboratories . 3 .14 Poliomyelitis . 3 .15 Depression and the End of Expansion . 3 .16 Table of Contents Endnotes – Glossary Credits Profiles Contact CPHA 1920This is Public Health: A Canadian1929 History 3.1 CHAPTER 3 Dominion Council of Health Modernization The .Dominion .Council .of .Health . was .chaired .by .the .federal .Deputy . Minister .of .Health .and .made .up .of . and Growth the .chief .provincial .officers .of .health . and .representatives .of .urban .and . A .new .public .health .order .emerged .in .the .aftermath .of .World .War .I, .represented .at .the . rural .women, .labour, .agriculture .and . universities, .the .latter .representing . international .level .by .the .development .of .the .Health .Organization .of .the .League .of .Nations . academic .and .scientific .expertise .in . In .Canada, .this .new .order .was .symbolized .by .the .Dominion .Council .of .Health .(DCH), .which . medicine, .public .health .and .laboratory . was .created .to .develop .policies .and .advise .the .new .federal .Department .of .Health . .Initially, . research . .The .Council .provided .a . the .Department .was .primarily .focused .on .collecting .and .distributing .information, .with .some . twice-yearly .forum .to .openly .discuss, . lesser .effort .to .develop .federal .laboratory .research .capacity . compare .and .co-ordinate .strategies .on . the .major .public .health .concerns .of .the . -

Latent Dangers in a Patent Pool: the European Commission's Approval of the 3G Wireless Technology Licensing Agreements

Latent Dangers in a Patent Pool: The European Commission's Approval of the 3G Wireless Technology Licensing Agreements Michael R. Franzingert TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................1695 I. B ackground .....................................................................................1698 A. The Evolution of Standards in the Wireless Communications Indu stry .....................................................................................1698 1. The 2G Mobile Telephone Standards .................................1698 2. The 3G Mobile Communication Standards ........................1699 B. Europe's Past Efforts at Standardization ..................................1700 C. Licensing of Essential Patents for 3G Standards ......................1702 II. The European Commission's Competition Law .............................1708 A. Article 81: The Foundation of European Antitrust Doctrine ...1709 B. New Block Exemptions, Individual Exemptions, and "C om fort L etters". ....................................................................1710 1. The Technology Transfer Block Exemption ......................1711 2. Exceptions Developed in Individual Cases ........................1712 III. A nalysis ...........................................................................................17 14 A. The Japanese Fair Trade Commission's Early Clearance of the Platform ..........................................................................1714 Copyright © 2003 -

The Spanish Flu and Canadian Influenza Vaccine Initiatives

DefiningMomentsCanada.ca THE SPANISH FLU AND CANADIAN INFLUENZA VACCINE INITIATIVES Christopher J. Rutty, Ph.D. significant but sometimes overlooked element in the history of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-19 A was the experimental production, distribution and wide use of influenza vaccines. Since the vaccines were based on an erroneous view that influenza was caused by a bacteria (the influenza virus would not be isolated until 1933) such vaccines were ineffective and thus of little importance to the course of the pandemic from a medical or public health perspective. However, the story of the vaccines produced to prevent pandemic influenza, particularly in Canada, reveals much about the application of uncertain knowledge in the face of an unprecedented public health emergency. It also reveals the changing state of Canadian biotechnology capacity at the end of World War I. Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories of the University of Toronto led the most significant initiative to produce an influenza vaccine.1 Connaught’s flu vaccine initiative coincided with a significant production effort by the Ontario Provincial Laboratories, along with various smaller scale and more local efforts, particularly in Kingston and Winnipeg.2 Canadian vaccine efforts were also linked to emergency vaccine preparation in New York City, Boston, and at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.3 Influenza vaccines were similarly prepared in other countries in the face of the global pandemic. In 1919, Dr. John G. FitzGerald, Director of Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories, began his summary of Connaught’s influenza vaccine work by observing: “almost coincident with the end of the war a great emergency arose in which the laboratories were provided with an opportunity of doing public service work of a national character.”4 Connaught had been established in May, 1914, as the Antitoxin Laboratory in the Department of Hygiene, 1 Online resources about the history of Connaught Laboratories include: http://connaught.research.utoronto.ca/history/; http:// thelegacyproject.ca 2 J.W.S. -

Research Versus Development: Patent Pooling, Innovation and Standardization in the Software Industry

RESEARCH VERSUS DEVELOPMENT: PATENT POOLING, INNOVATION AND STANDARDIZATION IN THE SOFTWARE INDUSTRY DANIEL LIN ABSTRACT Despite the impressive pace of modern invention, a certain "patent thicket" effect that may be impeding what has become an increasingly difficult road to the commercialization of new technologies. Specifically, as new technologies build upon old technologies, they necessarily become increasingly complex, and as a result, are often subject to the protection of multiple patents, covering both the new cumulative technologies as well as old foundational technologies. The difficulties of acquiring licenses (e.g. hold-out problems) for all such patents has the potential to stifle the development and commercialization of these new technologies. As such, patent pooling, once condemned as facilitating antitrust violations in past eras, has been reintroduced as a practice that, if properly structured, has potentially strong pro-competitive benefits. Patent pooling has the potential to reduce the level of research and invention in new technologies that can compete with an incumbent standard. Recent patent jurisprudence and lenient federal antitrust agency of recent patent pooling proposals seem to create an environment that encourages the resurgence of patent pooling. Copyright © 2002 The John Marshall Law School Cite as 1 J. MARSHALL REV. INTELL. PROP. L. 274 RESEARCH VERSUS DEVELOPMENT: PATENT POOLING, INNOVATION AND STANDARDIZATION IN THE SOFTWARE INDUSTRY DANIEL LIN* The master programmer stared at the novice. "And what would you do to remedy this state of affair?" he asked. The novice thought for a moment. "I will design a new editing program," he said, "a program that will replace all these others." Suddenly, the master struck the novice on the side of his head. -

U.S. Chamber of Commerce 2018 Special 301 Submission

By electronic submission Sung Chang Director for Innovation and IP Office of the U.S. Trade Representative Washington, DC U.S. CHAMBER OF COMMERCE 2018 SPECIAL 301 SUBMISSION Submitted electronically to USTR via http://www.regulations.gov, docket number USTR- 2017-0024. 1 February 8, 2018 Sung Chang Director for Innovation and IP Office of the U.S. Trade Representative 600 17th Street, NW Washington, DC 20508 Re: 2018 Special 301 Identification of Countries Under Section 182 of the Trade Act of 1974: Request for Public Comment and Announcement of Public Hearing, Office of the U.S. Trade Representative Dear Mr. Chang: The U.S. Chamber of Commerce’s (“U.S. Chamber” or “Chamber”) Global Innovation Policy Center (GIPC) is pleased to provide you with our submission for the U.S. Trade Representative’s Identification of Countries Under Section 182 of the Trade Act of 1974: Request for Public Comment. The Chamber has participated in this annual exercise to analyze the global intellectual property (IP) environment for many years and is encouraged that the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR) has prioritized its commitment to promote property rights as a way to foster development and prosperity. We urge the U.S. government to continue to use all available means to work with our trading partners to address these challenges. The Chamber is the world’s largest business federation representing the interests of more than three million businesses of all sizes, sectors, and regions, as well as state and local chambers and industry associations. It also houses the largest international staff within any business association, providing global coverage to advance the many policy interests of our members. -

Correspondence, Research Notes and Papers, Articles

MS BANTING (FREDERICK GRANT, SIR) PAPERS COLL Papers 76 Chronology Correspondence, research notes and papers, articles, speeches, travel journals, drawings, and sketches, photographs, clippings, and other memorabilia, awards and prizes. Includes some papers from his widow Henrietta Banting (d. 1976). 1908-1976. Extent: 63 boxes (approx. 8 metres) Part of the collection was deposited in the Library in 1957 by the “Committee concerned with the Banting Memorabilia”, which had been set up after the death of Banting in 1941. These materials included papers from Banting’s office. At the same time the books found in his office (largely scientific and medical texts and journals) were also deposited in the University Library. These now form a separate collection in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. The remainder of the collection was bequeathed to the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library by Banting’s widow, Dr. Henrietta Banting, in 1976. This part of the collection included materials collected by Henrietta Banting for her projected biography of F.G. Banting, as well as correspondence and memorabilia relating to her won career. Researchers who wish to publish extensively from previously unpublished material from this collection should discuss the question of literary rights with: Mrs. Nancy Banting 12420 Blackstock Street Maple Ridge, British Columbia V2X 5N6 (1989) Indicates a letter of application addressed to the Director, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, is needed due to fragility of originals or confidential nature of documents. 1 MS BANTING (FREDERICK GRANT, SIR) PAPERS COLL Papers 76 Chronology 1891 FGB born in Alliston, Ont. To Margaret (Grant) and William Thompson Banting. -

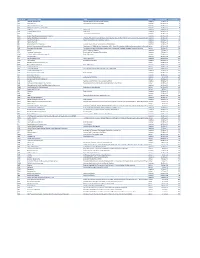

Mvx List.Pdf

MVX_CODE manufacturer_name Notes status last updated date manufacturer_id AB Abbott Laboratories includes Ross Products Division, Solvay Inactive 16-Nov-17 1 ACA Acambis, Inc acquired by sanofi in sept 2008 Inactive 28-May-10 2 AD Adams Laboratories, Inc. Inactive 16-Nov-17 3 ALP Alpha Therapeutic Corporation Inactive 16-Nov-17 4 AR Armour part of CSL Inactive 28-May-10 5 AVB Aventis Behring L.L.C. part of CSL Inactive 28-May-10 6 AVI Aviron acquired by Medimmune Inactive 28-May-10 7 BA Baxter Healthcare Corporation-inactive Inactive 28-May-10 8 BAH Baxter Healthcare Corporation includes Hyland Immuno, Immuno International AG,and North American Vaccine, Inc./acquired somInactive 16-Nov-17 9 BAY Bayer Corporation Bayer Biologicals now owned by Talecris Inactive 28-May-10 10 BP Berna Products Inactive 28-May-10 11 BPC Berna Products Corporation includes Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute Berne Inactive 16-Nov-17 12 BTP Biotest Pharmaceuticals Corporation New owner of NABI HB as of December 2007, Does NOT replace NABI Biopharmaceuticals in this codActive 28-May-10 13 MIP Emergent BioSolutions Formerly Emergent BioDefense Operations Lansing and Michigan Biologic Products Institute Active 16-Nov-17 14 CSL bioCSL bioCSL a part of Seqirus Inactive 26-Sep-16 15 CNJ Cangene Corporation Purchased by Emergent Biosolutions Inactive 29-Apr-14 16 CMP Celltech Medeva Pharmaceuticals Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 17 CEN Centeon L.L.C. Inactive 28-May-10 18 CHI Chiron Corporation Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 19 CON Connaught acquired by Merieux Inactive 28-May-10 21 DVC DynPort Vaccine Company, LLC Active 28-May-10 22 EVN Evans Medical Limited Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 23 GEO GeoVax Labs, Inc. -

Chronological Introduction of Types of Vaccine Products That Are Still Licensed in the United States

Appendix 2.3 CHRONOLOGICAL INTRODUCTION OF TYPES OF VACCINE PRODUCTS THAT ARE STILL LICENSED IN THE UNITED STATES The year of introduction of each of 49 of the 51 shown in table 2.3B, American pharmaceutical com- types of vaccine prducts currently licensed in the panies were issued 37 (89 percent) of the original United States, alolng with the manufacturing estab- licenses for these 42 products. New or improved lishment with the oldest license still in effect for each types of products that are currently licensed have product, is shown in table 2.3 A.] For 42 (86 percent) been introduced at a fairly consistent rate of three to of these 49 products, the establishment that received seven products per each 5-year interval since 1940.2 the original product license still holds this license. As Ten of the currently licensed products were licensed before 1940. Table 2.3A—Chronological Introduction of Types of Vaccine Products Still Licensed in the United States Year Type of vaccine product Establishment with oldest product license still in effecta 1903 Dlphtherla antitoxin Massachusetts Public Health Biologic Laboratories (191 7) 1907 Tetanus antitoxin Parke. Davis and Company (191 5) 1914 Pertussis vaccine Lederle Laboratories Typhoid vaccine Massachusetts Public Health Biologic Laboratories (191 7) Rabies vaccine . Eli Lilly and Company* 1917 Cholera vaccine Eli Lilly and Company* 1926 Diphtheria toxoid Parke, Davis and Company (1927) 1933 Staphylococcus toxoid Lederle Laboratories* Tetanus toxoid Merck Sharp and Dohme 1941 Typhus vaccine Eli Lilly and Company 1942 Plague vaccine .., . Cutter Laboratories* Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever vaccine. Lederle Laboratories* 1945 InfIuenza virus vaccine Lederle Laboratories Merck Sharp and Dohme Parke, Davis and Company * 1946 Parke, Davis and Company ● 1947 Parke, Davis and Company (1949) 1948 Parke, Davis and Company (1952) Parke. -

Patent Bullying”

\\jciprod01\productn\N\NDL\90-2\NDL203.txt unknown Seq: 1 30-DEC-14 16:13 THE VONAGE TRILOGY: A CASE STUDY IN “PATENT BULLYING” Ted Sichelman* ABSTRACT This Article presents an in-depth case study of a series of infringement suits filed by “patent bullies.” Unlike the oft-discussed “patent trolls”—which typically sell no products or services and perform no R&D—patent bullies are large, established operating companies that threaten or institute costly patent infringement actions of dubious merit against smaller companies, usually in order to suppress competition or garner licensing fees. In an ideal world of high-quality pat- ents and optimal patent licensing and litigation, infringement suits by aggressive incumbents would have a cleansing, almost Darwinian effect. Yet, defects and distortions in patent exami- nation, licensing, and litigation—the very problems that are raised constantly in the context of patent trolls—generally apply with equal and, often, greater force to patent bullies. Nonetheless, patent bullies have scarcely been discussed in the academic literature or popular press, especially in recent years. This Article examines three patent infringement suits filed by incumbent telecommunica- tions carriers—Sprint, Verizon, and AT&T—against Vonage, then an early-stage company pro- viding consumer telephone services over the Internet. Based on a detailed analysis of the patents- at-issue, prior art, court documents, and news accounts, it shows that the incumbents were able to exploit defects in the patent system in order to prevent disruptive technologies from competing with their outmoded products and services. Because startups like Vonage typically lack the resources to vigorously defend against even weak patent suits, patent bullying can result in severe anticompetitive effects. -

Patents and Standards

Patents and Standards A modern framework for IPR-based standardization FINAL REPORT A study prepared for the European Commission Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry This study was carried out for the European Commission by and as part of the DISCLAIMER By the European Commission, Directorate-General for Enterprise and Industry The information and views set out in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official opinion of the Commission. The Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this study. Neither the Commission nor any person acting on the Commission’s behalf may be held responsible for the use which may be made of the information contained therein. ISBN 978-92-79-35991-0 DOI: 10.2769/90861 © European Union, 2014. All rights reserved. Certain parts are licensed under conditions to the EU. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged. About ECSIP The European Competitiveness and Sustainable Industrial Policy Consortium, ECSIP Consortium for short, is the name chosen by the team of partners, subcontractors and individual experts that have agreed to work as one team for the purpose of the Framework Contract on ‘Industrial Competitiveness and Market Performance’. The Consortium is composed of Ecorys Netherlands (lead partner), Cambridge Econometrics, CASE, CSIL, Danish Technological Institute, Decision, Eindhoven University of Technology (ECIS), Euromonitor, Fratini Vergano, Frost & Sullivan, IDEA Consult, IFO Institute, MCI and wiiw, together with a group of 28 highly-skilled and specialised individuals. ECSIP Consortium p/a ECORYS Nederland BV Watermanweg 44 3067 GG Rotterdam P.O. Box 4175 3006 AD Rotterdam The Netherlands T. -

Licensing Intellectual Property in China

37 PATENT LITIGATION IN CHINA [Vol. 10 Licensing Intellectual Property in China 1 Lei Mei I. Introduction ........................................................................................... 37 II. Why China? ........................................................................................... 39 III. Current Ip Licensing Models ......................................................... 40 A. Two Types of IP Licensing ........................................................................... 40 B. Patent Licensing Models .............................................................................. 42 C. Deficiencies in Current Licensing Models ............................................. 42 IV. Develop A China-Oriented Strategy ............................................ 44 A. Develop Chinese Patent Portfolios .......................................................... 44 B. Understand the Chinese IP System .......................................................... 45 C. Structure Licensing Deals Creatively ..................................................... 46 V. Conclusion ............................................................................................. 48 I. INTRODUCTION Licensing is a viable method for many intellectual property (“IP”) owners to monetize their IP rights. While IP licensing practice is well developed in the United States, China remains a mysterious frontier for many IP owners. Even for large corporations that have developed successful licensing programs in 1 Lei Mei is the managing partner -

As Early As 1946, a Year Before Independence, the Government Of

Munich Personal RePEc Archive Gaining Technical Know-How in an Unequal World: Penicillin Manufacture in Nehru’s India Tyabji, Nasir April 2004 Online at https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/84236/ MPRA Paper No. 84236, posted 30 Jan 2018 04:51 UTC Gaining Technical Know-How in an Unequal World: Penicillin Manufacture in Nehru's India Nasir Tyabji I. Introduction For the first of the Jawaharlal Nehru Memorial lectures held at New Delhi in 1967, P.M.S. Blackett chose the theme of “Science and Technology in an Unequal World.”1 This was an apt choice of topic. For on the one hand, throughout his active public life, Jawaharlal Nehru had been convinced that the key to initiating a comprehensive process of development lay in the application of the results of scientific and technological enquiry to the problems confronting Indian society.2 Equally, Nehru was aware that India’s own scientific and technological base could not provide more than a small fraction of the effort required to provide the solutions to these problems.3 As the Prime Minister of Independent India, he was thus confronted with the task of identifying, and then accessing, foreign sources of technology. This was a task which raised complex issues, quite distinct from the technical problems of the “transfer of technology” from a foreign source to a local recipient.4 While Nehru’s experience as a nationalist politician might have provided him with an understanding of the power relations underlying the ground realities of international relations, the practical issues that might arise in the course of negotiating technology acquisitions could not be foreseen.