The Discovery of Insulin Revisited: Lessons for the Modern Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernization This Ispublic Health: Acanadianhistory

Table of Contents Endnotes – Glossary Credits Profiles Contact CPHA 1920This is Public Health: A Canadian1929 History CHAPTER 3 printable version of this chapter Modernization and Growth . 3 .1 Maternal and Child Health . 3 .2 Public Health Nurses . 3 .4 Full-Time Health Units . 3 .5 Services for Indigenous Communities . 3 .7 Venereal Disease . 3 .8 Charitable Organizations . 3 .9 Lapses in Oversight: Smallpox and Typhoid . 3 .11 Toronto’s School of Hygiene and Connaught Laboratories . 3 .14 Poliomyelitis . 3 .15 Depression and the End of Expansion . 3 .16 Table of Contents Endnotes – Glossary Credits Profiles Contact CPHA 1920This is Public Health: A Canadian1929 History 3.1 CHAPTER 3 Dominion Council of Health Modernization The .Dominion .Council .of .Health . was .chaired .by .the .federal .Deputy . Minister .of .Health .and .made .up .of . and Growth the .chief .provincial .officers .of .health . and .representatives .of .urban .and . A .new .public .health .order .emerged .in .the .aftermath .of .World .War .I, .represented .at .the . rural .women, .labour, .agriculture .and . universities, .the .latter .representing . international .level .by .the .development .of .the .Health .Organization .of .the .League .of .Nations . academic .and .scientific .expertise .in . In .Canada, .this .new .order .was .symbolized .by .the .Dominion .Council .of .Health .(DCH), .which . medicine, .public .health .and .laboratory . was .created .to .develop .policies .and .advise .the .new .federal .Department .of .Health . .Initially, . research . .The .Council .provided .a . the .Department .was .primarily .focused .on .collecting .and .distributing .information, .with .some . twice-yearly .forum .to .openly .discuss, . lesser .effort .to .develop .federal .laboratory .research .capacity . compare .and .co-ordinate .strategies .on . the .major .public .health .concerns .of .the . -

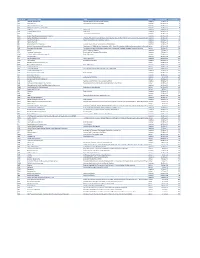

Osler Library of the History of Medicine Osler Library of the History of Medicine Duplicate Books for Sale, Arranged by Most Recent Acquisition

Osler Library of the History of Medicine Osler Library of the History of Medicine Duplicate books for sale, arranged by most recent acquisition. For more information please visit: http://www.mcgill.ca/osler-library/about/introduction/duplicate-books-for-sale/ # Author Title American Doctor's Odyssey: Adventures in Forty-Five Countries. New York: W.W. Norton, 1936. 2717 Heiser, Victor. 544 p. Ill. Fair. Expected and Unexpected: Childbirth in Prince Edward Island, 1827-1857: The Case Book of Dr. 2716 Mackieson, John. John Mackieson. St. John's, Newfoundland: Faculty of Medicine, Memorial University of Newfoundland, 1992. 114 p. Fine. The Woman Doctor of Balcarres. Hamilton, Ontario: Pathway Publications, 1984. 150 p. Very 2715 Steele, Phyllis L. good. The Diseases of Infancy and Childhood: For the Use of Students and Practitioners of Medicine. 2714 Holt, L. Emmett [New York: D. Appleton and Company, 1897.] Special Edition: Birmingham, Alabama: The Classics of Medicine Library, 1980. 1117 p. Ex libris: McGill University. Very Good. The Making of a Psychiatrist. New York: Arbor House, 1972. 410 p. Ex libris: McGill University. 2712 Viscott, David S. Good. Life of Sir William Osler. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1925. 2 vols. 685 and 728 p. Ex libris: McGill 2710 Cushing, Harvey. University. Fair (Rebound). Microbe Hunters. New York: Blue Ribbon Books, 1926. 363 p. Ex Libris: Norman H. Friedman; 2709 De Kruif, Paul McGill University. Very Good (Rebound). History of Medicine: A Scandalously Short Introduction" Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2708 Duffin, Jacalyn. 2000. Soft Cover. Condition: good. Stedman's Medical Dictionary. Baltimore: The Williams & Wilkins Company, 1966. -

The Medical & Scientific Library of W. Bruce

The Medical & Scientific Library of W. Bruce Fye New York I March 11, 2019 The Medical & Scientific Library of W. Bruce Fye New York | Monday March 11, 2019, at 10am and 2pm BONHAMS LIVE ONLINE BIDDING IS INQUIRIES CLIENT SERVICES 580 Madison Avenue AVAILABLE FOR THIS SALE New York Monday – Friday 9am-5pm New York, New York 10022 Please email bids.us@bonhams. Ian Ehling +1 (212) 644 9001 www.bonhams.com com with “Live bidding” in Director +1 (212) 644 9009 fax the subject line 48 hrs before +1 (212) 644 9094 PREVIEW the auction to register for this [email protected] ILLUSTRATIONS Thursday, March 7, service. Front cover: Lot 188 10am to 5pm Tom Lamb, Director Inside front cover: Lot 53 Friday, March 8, Bidding by telephone will only be Business Development Inside back cover: Lot 261 10am to 5pm accepted on a lot with a lower +1 (917) 921 7342 Back cover: Lot 361 Saturday, March 9, estimate in excess of $1000 [email protected] 12pm to 5pm REGISTRATION Please see pages 228 to 231 Sunday, March 10, Darren Sutherland, Specialist IMPORTANT NOTICE for bidder information including +1 (212) 461 6531 12pm to 5pm Please note that all customers, Conditions of Sale, after-sale [email protected] collection and shipment. All irrespective of any previous activity SALE NUMBER: 25418 with Bonhams, are required to items listed on page 231, will be Tim Tezer, Junior Specialist complete the Bidder Registration transferred to off-site storage +1 (917) 206 1647 CATALOG: $35 Form in advance of the sale. -

The Spanish Flu and Canadian Influenza Vaccine Initiatives

DefiningMomentsCanada.ca THE SPANISH FLU AND CANADIAN INFLUENZA VACCINE INITIATIVES Christopher J. Rutty, Ph.D. significant but sometimes overlooked element in the history of the Spanish Flu pandemic of 1918-19 A was the experimental production, distribution and wide use of influenza vaccines. Since the vaccines were based on an erroneous view that influenza was caused by a bacteria (the influenza virus would not be isolated until 1933) such vaccines were ineffective and thus of little importance to the course of the pandemic from a medical or public health perspective. However, the story of the vaccines produced to prevent pandemic influenza, particularly in Canada, reveals much about the application of uncertain knowledge in the face of an unprecedented public health emergency. It also reveals the changing state of Canadian biotechnology capacity at the end of World War I. Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories of the University of Toronto led the most significant initiative to produce an influenza vaccine.1 Connaught’s flu vaccine initiative coincided with a significant production effort by the Ontario Provincial Laboratories, along with various smaller scale and more local efforts, particularly in Kingston and Winnipeg.2 Canadian vaccine efforts were also linked to emergency vaccine preparation in New York City, Boston, and at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota.3 Influenza vaccines were similarly prepared in other countries in the face of the global pandemic. In 1919, Dr. John G. FitzGerald, Director of Connaught Antitoxin Laboratories, began his summary of Connaught’s influenza vaccine work by observing: “almost coincident with the end of the war a great emergency arose in which the laboratories were provided with an opportunity of doing public service work of a national character.”4 Connaught had been established in May, 1914, as the Antitoxin Laboratory in the Department of Hygiene, 1 Online resources about the history of Connaught Laboratories include: http://connaught.research.utoronto.ca/history/; http:// thelegacyproject.ca 2 J.W.S. -

The Science of Defence: Security, Research, and the North in Cold War Canada

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2017 The Science of Defence: Security, Research, and the North in Cold War Canada Matthew Shane Wiseman Wilfrid Laurier University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Wiseman, Matthew Shane, "The Science of Defence: Security, Research, and the North in Cold War Canada" (2017). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1924. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1924 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Science of Defence: Security, Research, and the North in Cold War Canada by Matthew Shane Wiseman B.A. (Hons) and B.Ed., Lakehead University, 2009 and 2010 M.A., Lakehead University, 2011 DISSERTATION Submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Degree in Doctor of Philosophy in History Wilfrid Laurier University Waterloo, Ontario, Canada © Matthew Shane Wiseman 2017 Abstract This dissertation examines the development and implementation of federally funded scientific defence research in Canada during the earliest decades of the Cold War. With a particular focus on the creation and subsequent activities of the Defence Research Board (DRB), Canada’s first peacetime military science organization, the history covered here crosses political, social, and environmental themes pertinent to a detailed analysis of defence-related government activity in the Canadian North. -

Correspondence, Research Notes and Papers, Articles

MS BANTING (FREDERICK GRANT, SIR) PAPERS COLL Papers 76 Chronology Correspondence, research notes and papers, articles, speeches, travel journals, drawings, and sketches, photographs, clippings, and other memorabilia, awards and prizes. Includes some papers from his widow Henrietta Banting (d. 1976). 1908-1976. Extent: 63 boxes (approx. 8 metres) Part of the collection was deposited in the Library in 1957 by the “Committee concerned with the Banting Memorabilia”, which had been set up after the death of Banting in 1941. These materials included papers from Banting’s office. At the same time the books found in his office (largely scientific and medical texts and journals) were also deposited in the University Library. These now form a separate collection in the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library. The remainder of the collection was bequeathed to the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library by Banting’s widow, Dr. Henrietta Banting, in 1976. This part of the collection included materials collected by Henrietta Banting for her projected biography of F.G. Banting, as well as correspondence and memorabilia relating to her won career. Researchers who wish to publish extensively from previously unpublished material from this collection should discuss the question of literary rights with: Mrs. Nancy Banting 12420 Blackstock Street Maple Ridge, British Columbia V2X 5N6 (1989) Indicates a letter of application addressed to the Director, Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library, is needed due to fragility of originals or confidential nature of documents. 1 MS BANTING (FREDERICK GRANT, SIR) PAPERS COLL Papers 76 Chronology 1891 FGB born in Alliston, Ont. To Margaret (Grant) and William Thompson Banting. -

Uot History Freidland.Pdf

Notes for The University of Toronto A History Martin L. Friedland UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO PRESS Toronto Buffalo London © University of Toronto Press Incorporated 2002 Toronto Buffalo London Printed in Canada ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 National Library of Canada Cataloguing in Publication Data Friedland, M.L. (Martin Lawrence), 1932– Notes for The University of Toronto : a history ISBN 0-8020-8526-1 1. University of Toronto – History – Bibliography. I. Title. LE3.T52F75 2002 Suppl. 378.7139’541 C2002-900419-5 University of Toronto Press acknowledges the financial assistance to its publishing program of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. This book has been published with the help of a grant from the Humanities and Social Sciences Federation of Canada, using funds provided by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. University of Toronto Press acknowledges the finacial support for its publishing activities of the Government of Canada, through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP). Contents CHAPTER 1 – 1826 – A CHARTER FOR KING’S COLLEGE ..... ............................................. 7 CHAPTER 2 – 1842 – LAYING THE CORNERSTONE ..... ..................................................... 13 CHAPTER 3 – 1849 – THE CREATION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO AND TRINITY COLLEGE ............................................................................................... 19 CHAPTER 4 – 1850 – STARTING OVER ..... .......................................................................... -

Mvx List.Pdf

MVX_CODE manufacturer_name Notes status last updated date manufacturer_id AB Abbott Laboratories includes Ross Products Division, Solvay Inactive 16-Nov-17 1 ACA Acambis, Inc acquired by sanofi in sept 2008 Inactive 28-May-10 2 AD Adams Laboratories, Inc. Inactive 16-Nov-17 3 ALP Alpha Therapeutic Corporation Inactive 16-Nov-17 4 AR Armour part of CSL Inactive 28-May-10 5 AVB Aventis Behring L.L.C. part of CSL Inactive 28-May-10 6 AVI Aviron acquired by Medimmune Inactive 28-May-10 7 BA Baxter Healthcare Corporation-inactive Inactive 28-May-10 8 BAH Baxter Healthcare Corporation includes Hyland Immuno, Immuno International AG,and North American Vaccine, Inc./acquired somInactive 16-Nov-17 9 BAY Bayer Corporation Bayer Biologicals now owned by Talecris Inactive 28-May-10 10 BP Berna Products Inactive 28-May-10 11 BPC Berna Products Corporation includes Swiss Serum and Vaccine Institute Berne Inactive 16-Nov-17 12 BTP Biotest Pharmaceuticals Corporation New owner of NABI HB as of December 2007, Does NOT replace NABI Biopharmaceuticals in this codActive 28-May-10 13 MIP Emergent BioSolutions Formerly Emergent BioDefense Operations Lansing and Michigan Biologic Products Institute Active 16-Nov-17 14 CSL bioCSL bioCSL a part of Seqirus Inactive 26-Sep-16 15 CNJ Cangene Corporation Purchased by Emergent Biosolutions Inactive 29-Apr-14 16 CMP Celltech Medeva Pharmaceuticals Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 17 CEN Centeon L.L.C. Inactive 28-May-10 18 CHI Chiron Corporation Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 19 CON Connaught acquired by Merieux Inactive 28-May-10 21 DVC DynPort Vaccine Company, LLC Active 28-May-10 22 EVN Evans Medical Limited Part of Novartis Inactive 28-May-10 23 GEO GeoVax Labs, Inc. -

Chronological Introduction of Types of Vaccine Products That Are Still Licensed in the United States

Appendix 2.3 CHRONOLOGICAL INTRODUCTION OF TYPES OF VACCINE PRODUCTS THAT ARE STILL LICENSED IN THE UNITED STATES The year of introduction of each of 49 of the 51 shown in table 2.3B, American pharmaceutical com- types of vaccine prducts currently licensed in the panies were issued 37 (89 percent) of the original United States, alolng with the manufacturing estab- licenses for these 42 products. New or improved lishment with the oldest license still in effect for each types of products that are currently licensed have product, is shown in table 2.3 A.] For 42 (86 percent) been introduced at a fairly consistent rate of three to of these 49 products, the establishment that received seven products per each 5-year interval since 1940.2 the original product license still holds this license. As Ten of the currently licensed products were licensed before 1940. Table 2.3A—Chronological Introduction of Types of Vaccine Products Still Licensed in the United States Year Type of vaccine product Establishment with oldest product license still in effecta 1903 Dlphtherla antitoxin Massachusetts Public Health Biologic Laboratories (191 7) 1907 Tetanus antitoxin Parke. Davis and Company (191 5) 1914 Pertussis vaccine Lederle Laboratories Typhoid vaccine Massachusetts Public Health Biologic Laboratories (191 7) Rabies vaccine . Eli Lilly and Company* 1917 Cholera vaccine Eli Lilly and Company* 1926 Diphtheria toxoid Parke, Davis and Company (1927) 1933 Staphylococcus toxoid Lederle Laboratories* Tetanus toxoid Merck Sharp and Dohme 1941 Typhus vaccine Eli Lilly and Company 1942 Plague vaccine .., . Cutter Laboratories* Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever vaccine. Lederle Laboratories* 1945 InfIuenza virus vaccine Lederle Laboratories Merck Sharp and Dohme Parke, Davis and Company * 1946 Parke, Davis and Company ● 1947 Parke, Davis and Company (1949) 1948 Parke, Davis and Company (1952) Parke. -

Calendar Is Brought to You By…

A Celebration of Canadian Healthcare Research Healthcare Canadian of Celebration A A Celebration of Canadian Healthcare Research Healthcare Canadian of Celebration A ea 000 0 20 ar Ye ea 00 0 2 ar Ye present . present present . present The Alumni and Friends of the Medical Research Council (MRC) Canada and Partners in Research in Partners and Canada (MRC) Council Research Medical the of Friends and Alumni The The Alumni and Friends of the Medical Research Council (MRC) Canada and Partners in Research in Partners and Canada (MRC) Council Research Medical the of Friends and Alumni The The Association of Canadian Medical Colleges, The Association of Canadian Teaching Hospitals, Teaching Canadian of Association The Colleges, Medical Canadian of Association The The Association of Canadian Medical Colleges, The Association of Canadian Teaching Hospitals, Teaching Canadian of Association The Colleges, Medical Canadian of Association The For further information please contact: The Dean of Medicine at any of Canada’s 16 medical schools (see list on inside front cover) and/or the Vice-President, Research at any of Canada’s 34 teaching hospitals (see list on inside front cover). • Dr. A. Angel, President • Alumni and Friends of MRC Canada e-mail address: [email protected] • Phone: (204) 787-3381 • Ron Calhoun, Executive Director • Partners in Research e-mail address: [email protected] • Phone: (519) 433-7866 Produced by: Linda Bartz, Health Research Awareness Week Project Director, Vancouver Hospital MPA Communication Design Inc.: Elizabeth Phillips, Creative Director • Spencer MacGillivray, Production Manager Forwords Communication Inc.: Jennifer Wah, ABC, Editorial Director A.K.A. Rhino Prepress & Print PS French Translation Services: Patrice Schmidt, French Translation Manager Photographs used in this publication were derived from the private collections of various medical researchers across Canada, The Canadian Medical Hall of Fame (London, Ontario), and First Light Photography (BC and Ontario). -

Sir Frederick Banting MD

Sir Frederick Banting MD October 31, 1920, after preparing for a lecture on the pancreas, Sir Frederick Grant Banting arose from a restless sleep and wrote down words that would forever change his life and the lives of millions suffering from Diabetes: "Diabetus [sic]. Ligate pancreatic ducts of dog. Keep dogs alive till acini degenerate leaving islets. Try to isolate the internal secretion of these and relieve glycosurea [sic]." This 25-word hypothesis would eventually lead to one of the most important medical discoveries of the 20th century and would gain Banting international fame and admiration. Determined to investigate his hypothesis, Banting was recommended to Dr. J.J.R. Macleod at The University of Toronto, where he was hesitantly given laboratory space to conduct experiments on the pancreas using dogs. Dr. Charles Best, a medical student at the time, was assigned to assist Banting’s research. Within a few months, Banting and Best had successfully isolated a protein hormone secreted by the pancreas, which was named insulin. With assistance from Dr. James Collip, the insulin was successfully refined and produced for clinical trials, which were immediately successful. Demonstrating his altruistic commitment to advance medicine, Banting sold the patent rights for insulin to The University of Toronto for $1, claiming that the discovery belonged to the world, not to him. This allowed insulin to be mass-produced, making it widely available to the public for the treatment of Diabetes. Although not a cure, this breakthrough would save millions of lives and, to this day, provides treatment for a disease that was previously considered a death sentence. -

Banting and Best: the Extraordinary Discovery of Insulin

106 Rev Port Endocrinol Diabetes Metab. 2017;12(1):106-115 Revista Portuguesa de Endocrinologia, Diabetes e Metabolismo www.spedmjournal.com Artigo de Revisão Banting and Best: The Extraordinary Discovery of Insulin Luís Cardosoa,b, Dírcea Rodriguesa,b, Leonor Gomesa,b, Francisco Carrilhoa a Department of Endocrinology, Diabetes, and Metabolism, Centro Hospitalar e Universitário de Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal b Faculty of Medicine of the University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal INFORMAÇÃO SOBRE O ARTIGO ABSTRACT Historial do artigo: Diabetes was a feared disease that most certainly led to death before insulin discovery. During the first Recebido a XX de XXXX de 201X two decades of the 20th century, several researchers tested pancreatic extracts, but most of them caused Aceite a XX de XXXX de 201X Online a 30 de junho de 2017 toxic reactions impeding human use. On May 1921, Banting, a young surgeon, and Best, a master’s student, started testing the hypothesis that, by ligating the pancreatic ducts to induce atrophy of the exocrine pancreas and minimizing the effect of digestive enzymes, it would be possible to isolate the Keywords: internal secretion of the pancreas. The research took place at the Department of Physiology of the Diabetes Mellitus University of Toronto under supervision of the notorious physiologist John MacLeod. Banting and Insulin/history Best felt several difficulties depancreatising dogs and a couple of weeks after the experiments had Pancreatic Extracts/history begun most of the dogs initially allocated to the project had succumbed to perioperative complications. When they had depancreatised dogs available, they moved to the next phase of the project and prepared pancreatic extracts from ligated atrophied pancreas.