A Bitter Truth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Phylogenetic Classification of Trametes

TAXON 60 (6) • December 2011: 1567–1583 Justo & Hibbett • Phylogenetic classification of Trametes SYSTEMATICS AND PHYLOGENY Phylogenetic classification of Trametes (Basidiomycota, Polyporales) based on a five-marker dataset Alfredo Justo & David S. Hibbett Clark University, Biology Department, 950 Main St., Worcester, Massachusetts 01610, U.S.A. Author for correspondence: Alfredo Justo, [email protected] Abstract: The phylogeny of Trametes and related genera was studied using molecular data from ribosomal markers (nLSU, ITS) and protein-coding genes (RPB1, RPB2, TEF1-alpha) and consequences for the taxonomy and nomenclature of this group were considered. Separate datasets with rDNA data only, single datasets for each of the protein-coding genes, and a combined five-marker dataset were analyzed. Molecular analyses recover a strongly supported trametoid clade that includes most of Trametes species (including the type T. suaveolens, the T. versicolor group, and mainly tropical species such as T. maxima and T. cubensis) together with species of Lenzites and Pycnoporus and Coriolopsis polyzona. Our data confirm the positions of Trametes cervina (= Trametopsis cervina) in the phlebioid clade and of Trametes trogii (= Coriolopsis trogii) outside the trametoid clade, closely related to Coriolopsis gallica. The genus Coriolopsis, as currently defined, is polyphyletic, with the type species as part of the trametoid clade and at least two additional lineages occurring in the core polyporoid clade. In view of these results the use of a single generic name (Trametes) for the trametoid clade is considered to be the best taxonomic and nomenclatural option as the morphological concept of Trametes would remain almost unchanged, few new nomenclatural combinations would be necessary, and the classification of additional species (i.e., not yet described and/or sampled for mo- lecular data) in Trametes based on morphological characters alone will still be possible. -

Diospyros Virginiana: Common Persimmon1 Edward F

ENH390 Diospyros virginiana: Common Persimmon1 Edward F. Gilman, Dennis G. Watson, Ryan W. Klein, Andrew K. Koeser, Deborah R. Hilbert, and Drew C. McLean2 Introduction Uses: fruit; reclamation; specimen; urban tolerant; highway median; bonsai An excellent small to medium tree, common persimmon is an interesting, somewhat irregularly-shaped native tree, for possible naturalizing in yards or parks. Bark is grey or black and distinctly blocky with orange in the valleys between the blocks. Fall color can be a spectacular red in USDA hardiness zones 4 through 8a. It is well adapted to cities, but presents a problem with fruit litter, attracting flies and scavengers, such as opossums and other mammals. Its mature height can be 60 feet, with branches spreading from 20 to 35 feet and a trunk two feet thick, but it is commonly much shorter in landscapes. The trunk typically ascends up through the crown in a curved but very dominant fashion, rarely producing double or multiple leaders. Lateral branches are typically much smaller in diameter than the trunk. General Information Scientific name: Diospyros virginiana Pronunciation: dye-OSS-pih-ross ver-jin-nee-AY-nuh Common name(s): common persimmon Family: Ebenaceae USDA hardiness zones: 4B through 9B (Figure 2) Origin: native to the southern two-thirds of the eastern United States UF/IFAS Invasive Assessment Status: native Figure 1. Full Form—Diospyros virginiana: common persimmon 1. This document is ENH390, one of a series of the Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date November 1993. Revised December 2018. Visit the EDIS website at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu for the currently supported version of this publication. -

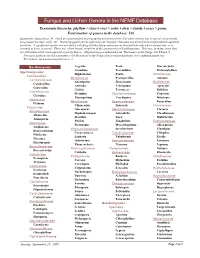

9B Taxonomy to Genus

Fungus and Lichen Genera in the NEMF Database Taxonomic hierarchy: phyllum > class (-etes) > order (-ales) > family (-ceae) > genus. Total number of genera in the database: 526 Anamorphic fungi (see p. 4), which are disseminated by propagules not formed from cells where meiosis has occurred, are presently not grouped by class, order, etc. Most propagules can be referred to as "conidia," but some are derived from unspecialized vegetative mycelium. A significant number are correlated with fungal states that produce spores derived from cells where meiosis has, or is assumed to have, occurred. These are, where known, members of the ascomycetes or basidiomycetes. However, in many cases, they are still undescribed, unrecognized or poorly known. (Explanation paraphrased from "Dictionary of the Fungi, 9th Edition.") Principal authority for this taxonomy is the Dictionary of the Fungi and its online database, www.indexfungorum.org. For lichens, see Lecanoromycetes on p. 3. Basidiomycota Aegerita Poria Macrolepiota Grandinia Poronidulus Melanophyllum Agaricomycetes Hyphoderma Postia Amanitaceae Cantharellales Meripilaceae Pycnoporellus Amanita Cantharellaceae Abortiporus Skeletocutis Bolbitiaceae Cantharellus Antrodia Trichaptum Agrocybe Craterellus Grifola Tyromyces Bolbitius Clavulinaceae Meripilus Sistotremataceae Conocybe Clavulina Physisporinus Trechispora Hebeloma Hydnaceae Meruliaceae Sparassidaceae Panaeolina Hydnum Climacodon Sparassis Clavariaceae Polyporales Gloeoporus Steccherinaceae Clavaria Albatrellaceae Hyphodermopsis Antrodiella -

Notes on Persimmons, Kakis, Date Plums, and Chapotes by STEPHEN A

Notes on Persimmons, Kakis, Date Plums, and Chapotes by STEPHEN A. SPONGBERG The genus Diospyros is not at present an important genus of orna- mental woody plants in North America, and while native persimmons once were valuable fruits in the eastern United States, the fruits pro- duced by Diospyros species no longer are important food items in the American home. In the countries of eastern Asia at least two species of Diospyros are among the most common trees encountered in door- yard gardens and orchards, where they are cultivated for their edible fruits as well as for other uses and for their ornamental beauty. J. J. Rein, a German traveler and author, wrote in 1889 that Diospyros kaki Linnaeus f. was "undeniably the most widely distributed, most important, and most beautiful fruit-tree in Japan, Corea, and North- ern China." And in Japan, where D. kaki is second in importance as an orchard crop only to citrus fruit, the kaki often is referred to as the national fruit (Childers, 1972). The rarity with which species of Diospyros are found in cultivation in cool-temperate North America is partially due to the fact that most are native to regions of tropical and subtropical climate and are not hardy in areas of temperate climate. A member of the Ebenaceae or Ebony Family, the genus contains upwards of 400 species that occur Stephen A. Spongberg is a horticultural taxonomist at the Arnold Arbore- tum. He participated in the Arboretum’s collecting trip to Japan and Korea in the fall of 1977, an experience which intensifted his interest in persim- mons. -

SELECTED NATIVE PLANTS for BIRDS and POLLINATORS in THE

SELECTED NATIVE PLANTS FOR BIRDS and POLLINATORS IN THE PIEDMONT AREA OF NORTH CAROLINA 12/31/2020 NC NC Wild Tend to # of Sun/ Soil Flower & fruit Drought Benefit to Audubon Flower of Common name Scientific name Height Width be deer caterpillars Special Notes Shade moisture dates tolerant Wildlife plant of the Year resistant supported the year Trees Maples Acer spp. NE,SE, LH 254 Red A. rubrum 40-75' 20-50' s-ps w,m Jan-Mar; Apr-Jul x x Southern Sugar A.floridanum 40-60' 40-60' s-ps m Apr-May; Jun-Oct 2018 Northern Sugar A. saccarum 60-80 25-60' s-ps m Apr-Jun; Jun-Sep 2018 Northern is drought sensitive Chalk A. leucoderme (native) 20-30' 15-25' s-ps m, d Mar-Apr; Apr-Sep x Pawpaws Asimina spp. BE, LH 12 Need more than one Common A. triloba, 8-35' 6-10' ps-sh m Mar-May; Aug-Oct x genetic strain for best fruit set. Dwarf A. parviflora 3-12' 2-6' s-ps m,d Apr–May; Jul–Sep x Species is drought sensitive. River birch Betula nigra 40-80' 15-25' s-ps w, m Mar-Apr; May-Jun x x LH, SE 299 Ironwood, Carpinus caroliniana 15-35' 12-18' s-sh w, m Mar-Apr; Sep-Oct SE, LH 71 Drought sensitive American hornbeam Size, growing conditions vary by Hickories Carya spp. 60-100' s-ps w, m, d Apr-May; Oct SE, LH 242 species Hackberries Celtis spp NE,BE,LH 47 Southern C. -

Rootstocks for the Oriental Persimmon

California Avocado association 1940 Yearbook 25: 43-44 Rootstocks for the Oriental Persimmon Robert W. Hodgson University of California, Los Angeles, Calif, From Proc. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci. Vol. 37, 1939. Prior to 1919, when the federal plant quarantine went into effect, most of the Oriental persimmon (Diospyros kaki) trees planted in California were imported from Japan and were on the kaki rootstock. While extensive planting of this fruit did not occur until after that period, many of the old trees still remain in a condition of good vigor and a few are known which are now between 50 and 60 years old. Though at least a dozen varieties were introduced in these importations, no evidence of a rootstock problem seems to have been reported. For the past two decades, however, the only rootstock employed commercially has been the lotus persimmon (Diospyros lotus). It is not altogether clear why California nurserymen chose this rootstock, though the difficulty of obtaining seed of the Oriental persimmon was probably an important reason. For the Hachiya variety, which has comprised probably 98 per cent of the trees propagated, the results appear to be satisfactory thus far, though the characteristic vigor of the young trees seems to be associated with excessive shedding of the immature fruits. However, it early became evident that Fuyu, a non-astringent variety of Japanese origin, did not behave like Hachiya on this rootstock. The graft-union was usually poor, and most of the trees grew slowly, came into bearing early, and declined within a few years. Although some thousands of trees have been propagated, it is difficult to find good trees more than 10 years old, and the general experience has been that most of the trees have declined before attaining that age. -

Common Persimmon

Ir,: Silvics of North America. Hardwoods. Agric. Handb. 654. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Agriculture: 294-298. Vol. 2. Diospyros virginiana L. Common Persimmon Ebenaceae Ebony family Lowell K. Halls Common persimmon (Diospyros uirginiana), also Soils and Topography called simmon, possumwood, and Florida persim- mon, is a slow-growing tree of moderate size found Common persimmon grows in a tremendous range on a wide variety of soils and sites. Best growth is of conditions from very dry, sterile, sandy woodlands in the bottom lands of the Mississippi River Valley. to river bottoms to rocky hillsides and moist or very The wood is close grained and sometimes used for dry locations. It thrives on almost any type of soil special products requiring hardness and strength. but is most frequently found growing on soils of the Persimmon is much better known for its fruits, how- orders Alfisols, Ultisols, Entisols, and Inceptisols. ever. They are enjoyed by people as well as many species of wildlife for food. The glossy leathery leaves Associated Forest Cover make the persimmon tree a nice one for landscaping, but it is not easily transplanted because of the Common persimmon is a key species in the forest taproot. cover type Sassafras-Persimmon (Society of American Foresters Type 64) (3) and is an associated species in the following cover types: Southern Scrub Habitat Oak (Type 721, Loblolly Pineshortleaf Pine (Type BO), Loblolly Pine-Hardwood (Type 82), Sweetgum- Native Range Willow Oak (Type 921, Sugarberry-American Elm- Green Ash (Type 931, Overcup Oak-Water Hickory Common persimmon (figs. 1, 2) is found from (Type 96), Baldcypress (Type 1011, and Baldcypress- southern Connecticut and Long Island to southern Tupelo (Type 102). -

Molecular Variations in Lenzites Species Collected from Nigeria And

Microbial Biosystems 3(2): 40–45 (2018) ISSN 2357-0334 http://fungiofegypt.com/Journal/index.htmlMicrobial Biosystems Copyright © 2018 Amrani and Abdel-Azeem Online Edition ARTICLE Molecular variations in Lenzites species collected from Nigeria and other parts of the world using Internal Transcribed Spacers (ITS) regions of Ribosomal RNA Oyetayo OV1* 1 Department of Microbiology, Federal University of Technology, P.M.B. 704, Akure, Nigeria. Oyetayo OV 2018 – Molecular variations in Lenzites species collected from Nigeria and other parts of the world using Internal Transcribed Spacers (ITS) regions of Ribosomal RNA. Microbial Biosystems 3(2), 40-45. Abstract The phylogeny of six specimens of Lenzites species collected from Akure Nigeria was studied using molecular data obtained by sequencing the internal transcribed spacers (ITS) regions of ribosomal RNA using universal primers (ITS4 and ITS5). Preliminary basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) revealed the identity of the specimens from Akure as Lenzites species. The percentage relationship between rRNA gene sequences of Lenzites species from Akure and Lenzites species sequences in NCBI GenBank database showed 99 to 100 similarity. Phylogenetic tree generated using MEGA 4 software strongly supported Lenzites clade that includes most Lenzites species together with species of Trametes and Daedalea which are considered as synonyms of Lenzites species. The rRNA gene sequences of three of the Lenzites species designated specimens 1, 3 and 6 were in the same clade with most of the Lenzites species collected from NCBI GenBank. Generally, specimens 1 to 6 form a monophyletic group with Lenzites species collected from other parts of the world. The results revealed the relationship of Lenzites species collected from Nigeria with Lenzites species with other parts of the world. -

Genera of Corticioid Fungi: Keys, Nomenclature and Taxonomy Article

Studies in Fungi 5(1): 125–309 (2020) www.studiesinfungi.org ISSN 2465-4973 Article Doi 10.5943/sif/5/1/12 Genera of corticioid fungi: keys, nomenclature and taxonomy Gorjón SP BIOCONS – Department of Botany and Plant Physiology, University of Salamanca, 37007 Salamanca, Spain Gorjón SP 2020 – Genera of corticioid fungi: keys, nomenclature, and taxonomy. Studies in Fungi 5(1), 125–309, Doi 10.5943/sif/5/1/12 Abstract A review of the worldwide corticioid homobasidiomycetes genera is presented. A total of 620 genera are considered with comments on their taxonomy and nomenclature. Of them, about 420 are accepted and keyed out, described in detail with remarks on their taxonomy and systematics. Key words – Corticiaceae – Crust fungi – Diversity – Homobasidiomycetes Introduction Corticioid fungi are a diverse and heterogeneous group of fungi mainly referred to basidiomycete fungi in which basidiomes are generally resupinate. Basidiome construction is often simple, and in most cases, only generative hyphae are found. In more structured basidiomes, those with a reflexed margin or with a pileate surface, more or less sclerified hyphae are usually found. Even the basidiome structure is apparently not very complex, hymenophore configuration should be highly variable finding smooth surfaces or different variations to increase the spore production area such as rugose, tuberculate, aculeate, merulioid, folded, or poroid hymenial surfaces. It is often thought that corticioid fungi produce unattractive and little variable forms and, in most cases, they go unnoticed by most mycologists as ungraceful forms that ‘cover sticks and look like a paint stain’. Although the macroscopic variability compared to other fungi is, but not always, usually limited, under the microscope they surprise with a great diversity of forms of basidia, cystidia, spores and other microscopic elements (Hjortstam et al. -

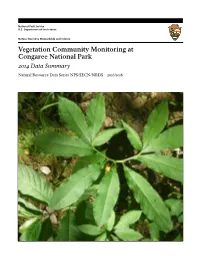

Vegetation Community Monitoring at Congaree National Park: 2014 Data Summary

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Vegetation Community Monitoring at Congaree National Park 2014 Data Summary Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2016/1016 ON THIS PAGE Tiny, bright yellow blossoms of Hypoxis hirsuta grace the forest floor at Congaree National Park. Photograph courtesy of Sarah C. Heath, Southeast Coast Network. ON THE COVER Spiraling compound leaf of green dragon (Arisaema dracontium) at Congaree National Park. Photograph courtesy of Sarah C. Heath, Southeast Coast Network Vegetation Community Monitoring at Congaree National Park 2014 Data Summary Natural Resource Data Series NPS/SECN/NRDS—2016/1016 Sarah Corbett Heath1 and Michael W. Byrne2 1National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network Cumberland Island National Seashore 101 Wheeler Street Saint Marys, GA 31558 2National Park Service Southeast Coast Inventory and Monitoring Network 135 Phoenix Drive Athens, GA 30605 May 2016 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado, publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics. These reports are of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Data Series is intended for the timely release of basic data sets and data summaries. Care has been taken to assure accuracy of raw data values, but a thorough analysis and interpretation of the data has not been completed. -

A Survey of Fungal Diversity in Northeast Ohio1

A Survey of Fungal Diversity in Northeast Ohio1 BRI'IT A. BUNYARD, Biology Department, Dauby Science Center, Ursuline College, Pepper Pike, OH 44124 ABSTRACT. Threats to our natural areas come from several sources; this problem is all too familiar in northeast Ohio. One of the goals of the Geauga County Park District is to protect high quality natural areas from rapidly encroaching development. One measure of an ecosystem's importance, as well as overall health, is in the biodiversity present. Furthermore, once the species diversity is assessed, this can be used to monitor the well-being of the ecosystem into the future. Currently, a paucity of information exists on the diversity of higher fungi in northern Ohio. The purpose of this two-year investigation was to inventory species of macrofungi present within The West Woods Park (Geauga Co., OH) and to evaluate overall diversity among different taxonomic groups of fungi present. Fruit bodies of Basidiomycetous and Ascomycetous fungi were collected weekly throughout the 2000 and 2001 growing seasons, identified using taxonomic keys, and photographed. At least 134 species from 30 families of Basidiomycetous fungi and at least 19 species from 11 families of Ascomycetous fungi were positively identified during this study. The results of this study were more extensive than from those of any previous survey in northeast Ohio. These findings point out the importance of The West Woods ecosystem to biodiversity of fungi in particular, possibly to overall biodiversity in general, and as an invaluable preserve for the northeast Ohio region. OHIO J SCI 103 (2):29-32, 2003 INTRODUCTION need for biodiversity assessment to evaluate the fates Fungi are among the most diverse groups of living of ever-decreasing natural habitats (Hawksworth 1991; organisms on earth, though inadequately studied world- National Research Council 1993; Cannon 1997; Rossman wide (Hawksworth 1991; Cannon 1997; Rossman and and Farr 1997). -

Designing an Oak Savanna

Savanna Information Sheet Conservation Practice Information Sheet (IS-MO643) Designing an Oak Savanna What is an Oak Savanna? Although definitions vary, one common definition is: an oak savanna is a plant community with scattered “open-grown” fire tolerant oak trees. Other terms for these savannas are “oak openings” and “barrens”. In contrast to a forest, which has a closed canopy, the oak savanna canopy ranges from about 10% to 50%. In such a habitat, the ground layer receives sun and shade, which permits growth of a wide diversity of grasses and flowering plants. There is usually enough sun to the ground to permit the growth of typical prairie species, such as big and little bluestem grass, and many goldenrods and asters. Oak savannas have their own characteristic and complex communities of ground-layer grasses, flowering plants, and shrubs. A few examples of flowering plants of the savanna include white wild indigo (Baptisia leucantha), lead plant (Amorpha canescens), purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea), round-headed bush clover (Lespedeza capitata) and blue aster (Aster anomalis). Common savanna shrubs are New Jersey tea (Ceonothus americanus), hazelnut (Corylus americana), and pasture rose (Rosa carolina) . Early settlers to the Midwest described the park-like setting of oak savannas. At one time these savannas and open woodlands were common throughout the landscape of Missouri. An oak savanna is a transitional form between tall grass prairie in the west and deciduous forest in the east. Although there is a continuum from prairie to savanna to forest, oak savannas are still considered a distinct vegetation type. An oak savanna is a fire-controlled vegetation community.