Designing an Oak Savanna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grassland & Shrubland Vegetation

Grassland & Shrubland Vegetation Missoula Draft Resource Management Plan Handout May 2019 Key Points Approximately 3% of BLM-managed lands in the planning area are non-forested (less than 10% canopy cover); the other 97% are dominated by a forested canopy with limited mountain meadows, shrublands, and grasslands. See table 1 on the following page for a break-down of BLM-managed grassland and shrubland in the planning area classified under the National Vegetation Classification System (NVCS). The overall management goal of grassland and shrubland resources is to maintain diverse upland ecological conditions while providing for a variety of multiple uses that are economically and biologically feasible. Alternatives Alternative A (1986 Garnet RMP, as Amended) Maintain, or where practical enhance, site productivity on all public land available for livestock grazing: (a) maintain current vegetative condition in “maintain” and “custodial” category allotments; (b) improve unsatisfactory vegetative conditions by one condition class in certain “improvement” category allotments; (c) prevent noxious weeds from invading new areas; and, (d) limit utilization levels to provide for plant maintenance. Alternatives B & C (common to all) Proposed objectives: Manage uplands to meet health standards and meet or exceed proper functioning condition within site or ecological capability. Where appropriate, fire would be used as a management agent to achieve/maintain disturbance regimes supporting healthy functioning vegetative conditions. Manage surface-disturbing activities in a manner to minimize degradation to rangelands and soil quality. Mange areas to conserve BLM special status species plants. Ensure consistency with achieving or maintaining Standards of Rangeland Health and Guidelines for Livestock Grazing Management for Montana, North Dakota, and South Dakota. -

Appendix L: Oak Savanna Definition

Appendix L: Oak Savanna Definition Appendix L: Oak Savanna Definition Working Definition of “Savanna” for shaded environments under trees, shifting as the tree canopy becomes more open or closed. Herba- Restoration Efforts at Crane Meadows ceous species typical of prairie and forest co-occur; NWR in addition to a set of very specific savanna species (see lists below) that have high fidelity to this com- General Definition of Southern Dry Savanna: munity type (Texler Personal commun., Drobney Personal commun. (Buchanan 1996). This spatial Savanna habitat at Crane Meadows NWR, like variation within the understory is a function of the savanna across its range, is a fire-dependent, varying degrees of species tolerance to shade and dynamic community characterized by scattered sun. Forbs are an essential component of the under trees or groves of trees, mostly comprised of oaks - story. Another important component of savanna (Quercus sp.) with a canopy cover ranging from 10– 70%, but more typically between 25-50%; and a understory is the shrub layer. The understory of basal area (BA) of 5-50 sq ft / acre. A wide range is savanna on the Anoka Sandplain, including those at Crane Meadows NWR, can be present with or with- used because canopy cover is not the most impor- tant characteristic that defines savanna and also out shrubs. The extent of shrub density is depen- because savanna ecosystems are dynamic and are dent on the subtype savanna classification and the frequency of fire (Law et al. 1994, Swanson 2008, associated with a natural range of variation through space and time. -

Key Points for Sustainable Management of Northern Great Plains Grasslands

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange Natural Resource Management Faculty Publications Department of Natural Resource Management 2019 Looking to the Future: Key Points for Sustainable Management of Northern Great Plains Grasslands Lora B. Perkins Marissa Ahlering Diane L. Larson Follow this and additional works at: https://openprairie.sdstate.edu/nrm_pubs Part of the Ecology and Evolutionary Biology Commons, and the Environmental Sciences Commons REVIEW ARTICLE Looking to the future: key points for sustainable management of northern Great Plains grasslands Lora B. Perkins1,2 , Marissa Ahlering3, Diane L. Larson4 The grasslands of the northern Great Plains (NGP) region of North America are considered endangered ecosystems and priority conservation areas yet have great ecological and economic importance. Grasslands in the NGP are no longer self-regulating adaptive systems. The challenges to these grasslands are widespread and serious (e.g. climate change, invasive species, fragmentation, altered disturbance regimes, and anthropogenic chemical loads). Because the challenges facing the region are dynamic, complex, and persistent, a paradigm shift in how we approach restoration and management of the grasslands in the NGP is imperative. The goal of this article is to highlight four key points for land managers and restoration practitioners to consider when planning management or restoration actions. First, we discuss the appropriateness of using historical fidelity as a restoration or management target because of changing climate, widespread pervasiveness of invasive species, the high level of fragmentation, and altered disturbance regimes. -

Tropical Deciduous Forests and Savannas

2/1/17 Tropical Coastal Communities Relationships to other tropical forest systems — specialized swamp forests: Tropical Coastal Forests Mangrove and beach forests § confined to tropical and & subtropical zones at the interface Tropical Deciduous Forests of terrestrial and saltwater Mangrove Forests Mangrove Forests § confined to tropical and subtropical § stilt roots - support ocean tidal zones § water temperature must exceed 75° F or 24° C in warmest month § unique adaptations to harsh Queensland, Australia environment - convergent Rhizophora mangle - red mangrove Moluccas Venezuela 1 2/1/17 Mangrove Forests Mangrove Forests § stilt roots - support § stilt roots - support § pneumatophores - erect roots for § pneumatophores - erect roots for O2 exchange O2 exchange § salt glands - excretion § salt glands - excretion § viviparous seedlings Rhizophora mangle - red mangrove Rhizophora mangle - red mangrove Xylocarpus (Meliaceae) & Rhizophora Mangrove Forests Mangrove Forests § 80 species in 30 genera (20 § 80 species in 30 genera (20 families) families) § 60 species OW& 20 NW § 60 species OW& 20 NW (Rhizophoraceae - red mangrove - Avicennia - black mangrove; inner Avicennia nitida (black mangrove, most common in Neotropics) boundary of red mangrove, better Acanthaceae) drained Rhizophora mangle - red mangrove Xylocarpus (Meliaceae) & Rhizophora 2 2/1/17 Mangrove Forests § 80 species in 30 genera (20 families) § 60 species OW& 20 NW Four mangrove families in one Neotropical mangrove community Avicennia - Rhizophora - Acanthanceae Rhizophoraceae -

Understanding the Causes of Bush Encroachment in Africa: the Key to Effective Management of Savanna Grasslands

Tropical Grasslands – Forrajes Tropicales (2013) Volume 1, 215−219 Understanding the causes of bush encroachment in Africa: The key to effective management of savanna grasslands OLAOTSWE E. KGOSIKOMA1 AND KABO MOGOTSI2 1Department of Agricultural Research, Ministry of Agriculture, Gaborone, Botswana. www.moa.gov.bw 2Department of Agricultural Research, Ministry of Agriculture, Francistown, Botswana. www.moa.gov.bw Keywords: Rangeland degradation, fire, indigenous ecological knowledge, livestock grazing, rainfall variability. Abstract The increase in biomass and abundance of woody plant species, often thorny or unpalatable, coupled with the suppres- sion of herbaceous plant cover, is a widely recognized form of rangeland degradation. Bush encroachment therefore has the potential to compromise rural livelihoods in Africa, as many depend on the natural resource base. The causes of bush encroachment are not without debate, but fire, herbivory, nutrient availability and rainfall patterns have been shown to be the key determinants of savanna vegetation structure and composition. In this paper, these determinants are discussed, with particular reference to arid and semi-arid environments of Africa. To improve our current under- standing of causes of bush encroachment, an integrated approach, involving ecological and indigenous knowledge systems, is proposed. Only through our knowledge of causes of bush encroachment, both direct and indirect, can better livelihood adjustments be made, or control measures and restoration of savanna ecosystem functioning be realized. Resumen Una forma ampliamente reconocida de degradación de pasturas es el incremento de la abundancia de especies de plan- tas leñosas, a menudo espinosas y no palatables, y de su biomasa, conjuntamente con la pérdida de plantas herbáceas. En África, la invasión por arbustos puede comprometer el sistema de vida rural ya que muchas personas dependen de los recursos naturales básicos. -

Carbon Sequestration in Managed Temperate Coniferous Forests Under Climate Change

Biogeosciences, 13, 1933–1947, 2016 www.biogeosciences.net/13/1933/2016/ doi:10.5194/bg-13-1933-2016 © Author(s) 2016. CC Attribution 3.0 License. Carbon sequestration in managed temperate coniferous forests under climate change Caren C. Dymond1, Sarah Beukema2, Craig R. Nitschke3, K. David Coates1, and Robert M. Scheller4 1Ministry of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, Government of British Columbia, Victoria, Canada 2ESSA Technologies Ltd., Vancouver, Canada 3School of Ecosystem and Forest Sciences, University of Melbourne, Richmond, Australia 4Department of Environmental Science and Management, Portland State University, Portland, USA Correspondence to: Caren C. Dymond ([email protected]) Received: 16 November 2015 – Published in Biogeosciences Discuss.: 21 December 2015 Revised: 11 March 2016 – Accepted: 16 March 2016 – Published: 30 March 2016 Abstract. Management of temperate forests has the poten- 1 Introduction tial to increase carbon sinks and mitigate climate change. However, those opportunities may be confounded by nega- tive climate change impacts. We therefore need a better un- As a global society, we depend on forests and land to take −1 derstanding of climate change alterations to temperate for- up about 2.5 C 1.3 PgC yr , about one-third of our fossil est carbon dynamics before developing mitigation strategies. emissions (Ciais et al., 2013). A reduction in the size of The purpose of this project was to investigate the interac- these sinks could accelerate global change by further increas- tions of species composition, fire, management, and climate ing the accumulation rate of greenhouse gases in the atmo- change in the Copper–Pine Creek valley, a temperate conifer- sphere. -

Shrubl Maritime Juniper Woodland/Shrubland

Maritime Juniper Woodland/ShrublWoodland/Shrublandand State Rank: S1 – Critically Imperiled The Maritime Juniper Woodland/ substrate stability; even Shrubland is a predominantly evergreen in stable situations community within the coastal salt spray community edges may zone; The trees tend to be short (less not be clear. Different than 15 feet) and scattered, with the types of communities tops sculpted by winds and salt spray; grade into and interdigitate with each forests, in areas of continuous changes of other. Very small patches levels of salt spray and substrate types. of any type within The dominant species is eastern red cedar another community (also called juniper), though the should be considered to Maritime Juniper Woodland/Shrubland above a abundance of red cedar is highly variable. be part of the variation of salt marsh. Photo: Patricia Swain, NHESP. It grows in association with scattered trees the main community. Description: Maritime Juniper and shrubs typical of the surrounding Maritime Pitch Pine Woodland/Shrublands occur on and vegetation such as pitch pine, various Woodlands on Dunes are between sand dunes, on the upper edges oaks, black cherry, red maple, blueberries, dominated by pitch pine. Maritime provide habitat for shrubland nesting birds of salt marshes and on cliffs and rocky huckleberries, sumac, and very often, Shrubland communities are dominated by and are important as feeding and resting/ headlands: all areas receiving salt spray poison ivy. Green briar can be abundant in a dense mixture of primarily deciduous roosting areas for migrating birds. from high winds. The maritime juniper more established woodlands, particularly shrubs, but may include red cedar. -

Black Oak Savanna Nature Centres 5 Summer Camp Sign-Up 6 by Kevin Tupman Oak Savanna

THE GRAND STRATEGY NEWSLETTER Volume 15, Number 3 - May-June 2010 Grand River The Grand: Conservation A Canadian Authority Heritage River Feature Fire restores a rare savanna forest 1 Milestones Byng island’s 50th 2 Look Who’s Taking Action Caring for bluebirds 3 Swallow habitat 4 Rotary forest 5 Fire restores a rare forest: What’s happening New programs at black oak savanna nature centres 5 Summer camp sign-up 6 By Kevin Tupman oak savanna. Older oaks now existing within the SWP update 6 Natural Heritage Specialist area are a testament to the vision, progressive for Grand River a grand its time, expressed in the master plan. place to paddle 7 ost people know that some plants and ani- Fire is necessary because this rare ecosystem Water festival photo 7 Mmals are at risk, such as the bald eagle and is sustained by fire. Historically, fire resulted American ginseng, but not many people realize from either lightning or aboriginal inhabitants. Now Available that communities such as forests, can also be at Fire ensures that savanna areas do not turn into Grand new risk. dense forests. Only trees with a high tolerance fishing book 7 It is true that sugar maple woodlots and pine for fire, such as the black oak, are able to sur- plantations are commonplace. However, the vive. European settlers cleared much of the savanna Calendar 8 GRCA is restoring one of the rarest of forests — for agriculture. They also suppressed the fires. a black oak savanna close to Apps’ Mill in Brant This meant that surviving pockets of savanna Cover photo County. -

New York City Approved Street Trees

New York City Approved Street Trees Suggested Tree Species Shape Visual interest Frequency of Preferred Cultivars Notes Scientific Name Common Name Planting Acer rubrum Red Maple Sparingly 'Red Sunset' ALB Host Aesculus hippocastanum Horsechestnut White May flowers Sparingly 'Baumanni' ALB Host Aesculus octandra Yellow Buckeye Yellow May Flowers Sparingly ALB Host ALB Host 'Duraheat' Betula nigra River Birch Ornamental Bark Sparingly Plant Single Stem 'Heritage' Only Celtis occidentalis Hackberry Ornamental Bark Sparingly 'Magnifica' ALB Host ALB Host Cercidiphyllum japonicum Katsura Tree Sparingly Plant Single Stem Only Corylus colurna Turkish Filbert Sparingly LARGE TREES: Mature LARGE TREES: height than greater feet 50 tall Eucommia ulmoides Hardy Rubber Tree Frequently 'Asplenifolia' Fagus sylvatica European Beech Sparingly 'Dawyckii Purple' 'Autumn Gold' Ginkgo biloba Ginkgo Yellow Fall Color Moderately 'Magyar' Very Tough Tree 'Princeton Sentry' 'Shademaster' 'Halka' Gleditsia triacanthos var inermis Honeylocust Yellow Fall Color Moderately 'Imperial' 'Skyline' 'Espresso' Gymnocladus dioicus Kentucky Coffeetree Large Tropical Leaves Frequently 'Prairie Titan' Page 1 of 7 New York City Approved Street Trees Suggested Tree Species Shape Visual interest Frequency of Preferred Cultivars Notes Scientific Name Common Name Planting 'Rotundiloba' Seedless Cultivars Liquidambar styraciflua Sweetgum Excellent Fall Color Frequently 'Worplesdon' Preffered 'Cherokee' Orange/Green June Liriodendron tulipifera Tulip Tree Moderately Flowers Metasequoia -

Checklist of Illinois Native Trees

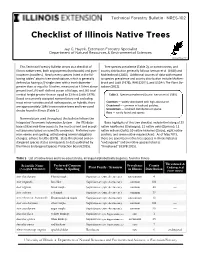

Technical Forestry Bulletin · NRES-102 Checklist of Illinois Native Trees Jay C. Hayek, Extension Forestry Specialist Department of Natural Resources & Environmental Sciences Updated May 2019 This Technical Forestry Bulletin serves as a checklist of Tree species prevalence (Table 2), or commonness, and Illinois native trees, both angiosperms (hardwoods) and gym- county distribution generally follows Iverson et al. (1989) and nosperms (conifers). Nearly every species listed in the fol- Mohlenbrock (2002). Additional sources of data with respect lowing tables† attains tree-sized stature, which is generally to species prevalence and county distribution include Mohlen- defined as having a(i) single stem with a trunk diameter brock and Ladd (1978), INHS (2011), and USDA’s The Plant Da- greater than or equal to 3 inches, measured at 4.5 feet above tabase (2012). ground level, (ii) well-defined crown of foliage, and(iii) total vertical height greater than or equal to 13 feet (Little 1979). Table 2. Species prevalence (Source: Iverson et al. 1989). Based on currently accepted nomenclature and excluding most minor varieties and all nothospecies, or hybrids, there Common — widely distributed with high abundance. are approximately 184± known native trees and tree-sized Occasional — common in localized patches. shrubs found in Illinois (Table 1). Uncommon — localized distribution or sparse. Rare — rarely found and sparse. Nomenclature used throughout this bulletin follows the Integrated Taxonomic Information System —the ITIS data- Basic highlights of this tree checklist include the listing of 29 base utilizes real-time access to the most current and accept- native hawthorns (Crataegus), 21 native oaks (Quercus), 11 ed taxonomy based on scientific consensus. -

Robert Grau Memorial Oak Savanna Trail Guide

Robert Grau Robert Grau was a forester and a true conservationist. He was a charter member of Robert Grau the Clayton County Conservation Board from 1958-1978, and he was one of the first to Memorial Oak reconstruct a prairie in Clayton County in the late 1970's . The reconstruction of Savanna Trail this Oak Savanna is dedicated to his memory. Guide 29862 Osborne Road Elkader, IA 52043 Clayton County (563)-245-1516 Robert Grau with his son and grandsons Conservation Board Welcome! Prairie Reconstruction Oak Savanna Welcome to the Robert Grau Memorial Oak As you make your way up the first hill, you’ll notice a At the top of the hill, you have a good view of the oak Savanna and Trail! Use this brochure to help large open prairie off to the right. Prairie was once savanna. Savannas are open landscapes of widely guide you along the trail. We hope you enjoy common in NE Iowa. The original spaced, broad-crowned trees and a diverse mix of your visit! prairie around the village of Motor shrubs, grasses, and wildflowers. Once common in was turned into farmland when the NE Iowa’s hills and river valleys, savannas are now Limestone Kiln Klink family bought Motor Mill and rare, due to land use change for farming and building. At the beginning of the trail next to the road, just past surrounding buildings in 1903. the Cooperage, is where a lime kiln was once located. Clayton County Conservation Limestone Quarry acquired the site in 1983 and has The kiln would have been used during the late 1860’s Once at the top of the hill, you will notice a large since restored this area to prairie when Motor Mill was being constructed. -

Native Or Suitable Plants City of Mccall

Native or Suitable Plants City of McCall The following list of plants is presented to assist the developer, business owner, or homeowner in selecting plants for landscaping. The list is by no means complete, but is a recommended selection of plants which are either native or have been successfully introduced to our area. Successful landscaping, however, requires much more than just the selection of plants. Unless you have some experience, it is suggested than you employ the services of a trained or otherwise experienced landscaper, arborist, or forester. For best results it is recommended that careful consideration be made in purchasing the plants from the local nurseries (i.e. Cascade, McCall, and New Meadows). Plants brought in from the Treasure Valley may not survive our local weather conditions, microsites, and higher elevations. Timing can also be a serious consideration as the plants may have already broken dormancy and can be damaged by our late frosts. Appendix B SELECTED IDAHO NATIVE PLANTS SUITABLE FOR VALLEY COUNTY GROWING CONDITIONS Trees & Shrubs Acer circinatum (Vine Maple). Shrub or small tree 15-20' tall, Pacific Northwest native. Bright scarlet-orange fall foliage. Excellent ornamental. Alnus incana (Mountain Alder). A large shrub, useful for mid to high elevation riparian plantings. Good plant for stream bank shelter and stabilization. Nitrogen fixing root system. Alnus sinuata (Sitka Alder). A shrub, 6-1 5' tall. Grows well on moist slopes or stream banks. Excellent shrub for erosion control and riparian restoration. Nitrogen fixing root system. Amelanchier alnifolia (Serviceberry). One of the earlier shrubs to blossom out in the spring.