Direct Interference with Rhamnogalacturonan I Biosynthesis in Golgi Vesicles1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

METACYC ID Description A0AR23 GO:0004842 (Ubiquitin-Protein Ligase

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for Integrative Biology This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2012 Heat Stress Responsive Zostera marina Genes, Southern Population (α=0. -

Supplemental Information to Mammadova-Bach Et Al., “Laminin Α1 Orchestrates VEGFA Functions in the Ecosystem of Colorectal Carcinogenesis”

Supplemental information to Mammadova-Bach et al., “Laminin α1 orchestrates VEGFA functions in the ecosystem of colorectal carcinogenesis” Supplemental material and methods Cloning of the villin-LMα1 vector The plasmid pBS-villin-promoter containing the 3.5 Kb of the murine villin promoter, the first non coding exon, 5.5 kb of the first intron and 15 nucleotides of the second villin exon, was generated by S. Robine (Institut Curie, Paris, France). The EcoRI site in the multi cloning site was destroyed by fill in ligation with T4 polymerase according to the manufacturer`s instructions (New England Biolabs, Ozyme, Saint Quentin en Yvelines, France). Site directed mutagenesis (GeneEditor in vitro Site-Directed Mutagenesis system, Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France) was then used to introduce a BsiWI site before the start codon of the villin coding sequence using the 5’ phosphorylated primer: 5’CCTTCTCCTCTAGGCTCGCGTACGATGACGTCGGACTTGCGG3’. A double strand annealed oligonucleotide, 5’GGCCGGACGCGTGAATTCGTCGACGC3’ and 5’GGCCGCGTCGACGAATTCACGC GTCC3’ containing restriction site for MluI, EcoRI and SalI were inserted in the NotI site (present in the multi cloning site), generating the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. The SV40 polyA region of the pEGFP plasmid (Clontech, Ozyme, Saint Quentin Yvelines, France) was amplified by PCR using primers 5’GGCGCCTCTAGATCATAATCAGCCATA3’ and 5’GGCGCCCTTAAGATACATTGATGAGTT3’ before subcloning into the pGEMTeasy vector (Promega, Charbonnières-les-Bains, France). After EcoRI digestion, the SV40 polyA fragment was purified with the NucleoSpin Extract II kit (Machery-Nagel, Hoerdt, France) and then subcloned into the EcoRI site of the plasmid pBS-villin-promoter-MES. Site directed mutagenesis was used to introduce a BsiWI site (5’ phosphorylated AGCGCAGGGAGCGGCGGCCGTACGATGCGCGGCAGCGGCACG3’) before the initiation codon and a MluI site (5’ phosphorylated 1 CCCGGGCCTGAGCCCTAAACGCGTGCCAGCCTCTGCCCTTGG3’) after the stop codon in the full length cDNA coding for the mouse LMα1 in the pCIS vector (kindly provided by P. -

Supplementary Materials

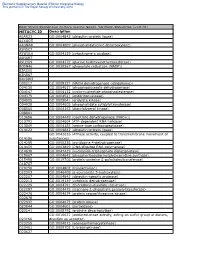

1 Supplementary Materials: Supplemental Figure 1. Gene expression profiles of kidneys in the Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice. (A) A heat map of microarray data show the genes that significantly changed up to 2 fold compared between Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice (N=4 mice per group; p<0.05). Data show in log2 (sample/wild-type). 2 Supplemental Figure 2. Sting signaling is essential for immuno-phenotypes of the Fcgr2b-/-lupus mice. (A-C) Flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes isolated from wild-type, Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice at the age of 6-7 months (N= 13-14 per group). Data shown in the percentage of (A) CD4+ ICOS+ cells, (B) B220+ I-Ab+ cells and (C) CD138+ cells. Data show as mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001). 3 Supplemental Figure 3. Phenotypes of Sting activated dendritic cells. (A) Representative of western blot analysis from immunoprecipitation with Sting of Fcgr2b-/- mice (N= 4). The band was shown in STING protein of activated BMDC with DMXAA at 0, 3 and 6 hr. and phosphorylation of STING at Ser357. (B) Mass spectra of phosphorylation of STING at Ser357 of activated BMDC from Fcgr2b-/- mice after stimulated with DMXAA for 3 hour and followed by immunoprecipitation with STING. (C) Sting-activated BMDC were co-cultured with LYN inhibitor PP2 and analyzed by flow cytometry, which showed the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IAb expressing DC (N = 3 mice per group). 4 Supplemental Table 1. Lists of up and down of regulated proteins Accession No. -

![A Label-Free Cellular Proteomics Approach to Decipher the Antifungal Action of Dimiq, a Potent Indolo[2,3- B]Quinoline Agent, Against Candida Albicans Biofilms](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9827/a-label-free-cellular-proteomics-approach-to-decipher-the-antifungal-action-of-dimiq-a-potent-indolo-2-3-b-quinoline-agent-against-candida-albicans-biofilms-409827.webp)

A Label-Free Cellular Proteomics Approach to Decipher the Antifungal Action of Dimiq, a Potent Indolo[2,3- B]Quinoline Agent, Against Candida Albicans Biofilms

A Label-Free Cellular Proteomics Approach to Decipher the Antifungal Action of DiMIQ, a Potent Indolo[2,3- b]Quinoline Agent, against Candida albicans Biofilms Robert Zarnowski 1,2*, Anna Jaromin 3*, Agnieszka Zagórska 4, Eddie G. Dominguez 1,2, Katarzyna Sidoryk 5, Jerzy Gubernator 3 and David R. Andes 1,2 1 Department of Medicine, School of Medicine & Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA; [email protected] (E.G.D.); [email protected] (D.R.A.) 2 Department of Medical Microbiology, School of Medicine & Public Health, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, WI 53706, USA 3 Department of Lipids and Liposomes, Faculty of Biotechnology, University of Wroclaw, 50-383 Wroclaw, Poland; [email protected] 4 Department of Medicinal Chemistry, Jagiellonian University Medical College, 30-688 Cracow, Poland; [email protected] 5 Department of Pharmacy, Cosmetic Chemicals and Biotechnology, Team of Chemistry, Łukasiewicz Research Network-Industrial Chemistry Institute, 01-793 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (R.Z.); [email protected] (A.J.); Tel.: +1-608-265-8578 (R.Z.); +48-71-3756203 (A.J.) Label-Free Cellular Proteomics of Candida albicans biofilms treated with DiMIQ Identified Proteins Accession # Alternate ID Gene names (ORF ) WT DIMIQ Z SCORE Proteins induced by DiMIQ Arginase (EC 3.5.3.1) A0A1D8PP00 CAR1 CAALFM_C504490CA 0.000 6.648 drug induced Glucan 1,3-beta-glucosidase BGL2 (EC 3.2.1.58) (Exo-1Q5AMT2 BGL2 CAALFM_C402250CA -

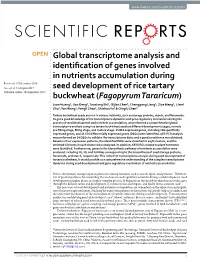

Global Transcriptome Analysis and Identification of Genes Involved In

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Global transcriptome analysis and identification of genes involved in nutrients accumulation during Received: 19 December 2016 Accepted: 31 August 2017 seed development of rice tartary Published: xx xx xxxx buckwheat (Fagopyrum Tararicum) Juan Huang1, Jiao Deng1, Taoxiong Shi1, Qijiao Chen1, Chenggang Liang1, Ziye Meng1, Liwei Zhu1, Yan Wang1, Fengli Zhao2, Shizhou Yu3 & Qingfu Chen1 Tartary buckwheat seeds are rich in various nutrients, such as storage proteins, starch, and flavonoids. To get a good knowledge of the transcriptome dynamics and gene regulatory mechanism during the process of seed development and nutrients accumulation, we performed a comprehensive global transcriptome analysis using rice tartary buckwheat seeds at different development stages, namely pre-filling stage, filling stage, and mature stage. 24 819 expressed genes, including 108 specifically expressed genes, and 11 676 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified. qRT-PCR analysis was performed on 34 DEGs to validate the transcriptome data, and a good consistence was obtained. Based on their expression patterns, the identified DEGs were classified to eight clusters, and the enriched GO items in each cluster were analyzed. In addition, 633 DEGs related to plant hormones were identified. Furthermore, genes in the biosynthesis pathway of nutrients accumulation were analyzed, including 10, 20, and 23 DEGs corresponding to the biosynthesis of seed storage proteins, flavonoids, and starch, respectively. This is the first transcriptome analysis during seed development of tartary buckwheat. It would provide us a comprehensive understanding of the complex transcriptome dynamics during seed development and gene regulatory mechanism of nutrients accumulation. Seed is the primary storage organ in plants for storing nutrients such as starch, lipids, and proteins1. -

Supplementary Information

Supplementary Information Table S1. Pathway analysis of the 1246 dwf1-specific differentially expressed genes. Fold Change Fold Change Fold Change Gene ID Description (dwf1/WT) (XL-5/WT) (XL-6/WT) Carbohydrate Metabolism Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis POPTR_0008s11770.1 Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase −1.7382 0.512146 0.168727 POPTR_0001s47210.1 Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, class I 1.599591 0.044778 0.18237 POPTR_0011s05190.3 Probable phosphoglycerate mutase −2.11069 −0.34562 −0.9738 POPTR_0012s01140.1 Pyruvate kinase −1.25054 0.074697 −0.16016 POPTR_0016s12760.1 Pyruvate decarboxylase 2.664081 0.021062 0.371969 POPTR_0012s08010.1 Aldehyde dehydrogenase (NAD+) −1.41556 0.479957 −0.21366 POPTR_0014s13710.1 Acetyl-CoA synthetase −1.337 0.154552 −0.26532 POPTR_0017s11660.1 Aldose 1-epimerase 2.770518 0.016874 0.73016 POPTR_0010s11970.1 Phosphoglucomutase −1.25266 −0.35581 0.074064 POPTR_0012s14030.1 Phosphoglucomutase −1.15872 −0.68468 −0.93596 POPTR_0002s10850.1 Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (ATP) 1.489119 0.967284 0.821559 Citrate cycle (TCA cycle) 2-Oxoglutarate dehydrogenase E2 component POPTR_0014s15280.1 −1.63733 0.076435 0.170827 (dihydrolipoamide succinyltransferase) POPTR_0002s26120.1 Succinyl-CoA synthetase β subunit −1.29244 −0.38517 −0.3497 POPTR_0007s12750.1 Succinate dehydrogenase (ubiquinone) flavoprotein subunit −1.83751 0.519356 0.309149 POPTR_0002s10850.1 Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (ATP) 1.489119 0.967284 0.821559 Pentose phosphate pathway POPTR_0008s11770.1 Glucose-6-phosphate isomerase −1.7382 0.512146 0.168727 POPTR_0013s00660.1 Glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase −1.26949 −0.18314 0.374822 POPTR_0015s00960.1 6-Phosphogluconolactonase 2.022223 0.168877 0.971431 POPTR_0010s11970.1 Phosphoglucomutase −1.25266 −0.35581 0.074064 POPTR_0012s14030.1 Phosphoglucomutase −1.15872 −0.68468 −0.93596 POPTR_0001s47210.1 Fructose-bisphosphate aldolase, class I 1.599591 0.044778 0.18237 S2 Table S1. -

Recent Progress Toward Understanding the Role of Starch Biosynthetic Enzymes in the Cereal Endosperm

Amylase 2017; 1: 59–74 Review Article Cheng Li, Prudence O. Powell, Robert G. Gilbert* Recent progress toward understanding the role of starch biosynthetic enzymes in the cereal endosperm DOI 10.1515/amylase-2017-0006 Abbreviations: ADPGlc, adenosine 5'-diphosphate Received July 31, 2017; accepted September 22, 2017 glucose; AGPase, ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase; Abstract: Starch from cereal endosperm is a major CBM, carbohydrate-binding module; CLD, chain-length energy source for many mammals. The synthesis of this distribution; DAF, days after flowering; DBE, debranching starch involves a number of different enzymes whose enzyme; D-enzyme, disproportionating enzyme; mode of action is still not completely understood. ADP- DP, degree of polymerization; GBSS, granule bound glucose pyrophosphorylase is involved in the synthesis starch synthase; GH, glycoside hydrolase; GT, glycosyl of starch monomer (ADP-glucose), a process, which transferase; ISA, isoamylase; MOS, maltooligosaccharides; almost exclusively takes place in the cytosol. ADP- 3-PGA, 3-phosphoglyceric acid; Pi, inorganic phosphate; glucose is then transported into the amyloplast and PUL, pullulanase; SBE, starch-branching enzyme; SP, incorporated into starch granules by starch synthase, starch phosphorylase; SS, starch synthases; SuSy, sucrose starch-branching enzyme and debranching enzyme. synthase; UDPGlc, nucleoside diphosphate glucose. Additional enzymes, including starch phosphorylase and disproportionating enzyme, may be also involved in the formation of starch granules, although their exact 1 Introduction functions are still obscure. Interactions between these Starch is a highly branched d-glucose homopolymer enzymes in the form of functional complexes have been with a wide range of uses. It is accumulated in the cereal proposed and investigated, resulting more complicated endosperm as an energy reserve for seed germination, as starch biosynthetic pathways. -

アミロース製造に利用する酵素の開発と改良 Phosphorylase and Muscle Phosphorylase B

125 J. Appl. Glycosci., 54, 125―131 (2007) !C 2007 The Japanese Society of Applied Glycoscience Proceedings of the Symposium on Amylases and Related Enzymes, 2006 Developing and Engineering Enzymes for Manufacturing Amylose (Received December 5, 2006; Accepted January 5, 2007) Michiyo Yanase,1,* Takeshi Takaha1 and Takashi Kuriki1 1 Biochemical Research Laboratory, Ezaki Glico Co., Ltd. (4 ―6 ―5, Utajima, Nishiyodogawa-ku, Osaka 555-8502, Japan) Abstract: Amylose is a functional biomaterial and is expected to be used for various industries. However at present, manufacturing of amylose is not done, since the purification of amylose from starch is very difficult. It has been known that amylose can be produced in vitro by using α-glucan phosphorylases. In order to ob- tain α-glucan phosphorylase suitable for manufacturing amylose, we isolated an α-glucan phosphorylase gene from Thermus aquaticus and expressed it in Escherichia coli. We also obtained thermostable α-glucan phos- phorylase by introducing amino acid replacement onto potato enzyme. α-Glucan phosphorylase is suitable for the synthesis of amylose; the only problem is that it requires an expensive substrate, glucose 1-phosphate. We have avoided this problem by using α-glucan phosphorylase either with sucrose phosphorylase or cellobiose phosphorylase, where inexpensive raw material, sucrose or cellobiose, can be used instead. In these combined enzymatic systems, α-glucan phosphorylase is a key enzyme. This paper summarizes our work on engineering practical α-glucan phosphorylase for industrial processes and its use in the enzymatic synthesis of essentially linear amylose and other glucose polymers. Key words: amylose, glucose polymer, α-glucan phosphorylase, glycogen debranching enzyme, protein engi- neering α-1,4 glucan is the major form of energy reserve from Enzymes for amylose synthesis. -

1 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 1 2 an Archaeal Symbiont

1 SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION 2 3 An archaeal symbiont-host association from the deep terrestrial subsurface 4 5 Katrin Schwank1, Till L. V. Bornemann1, Nina Dombrowski2, Anja Spang2,3, Jillian F. Banfield4 and 6 Alexander J. Probst1* 7 8 9 1 Group for Aquatic Microbial Ecology (GAME), Biofilm Center, Department of Chemistry, 10 University of Duisburg-Essen, Germany 11 2Department of Marine Microbiology and Biogeochemistry (MMB), Royal Netherlands Institute 12 for Sea Research (NIOZ), and Utrecht University, Den Burg, Netherlands 13 3Department of Cell- and Molecular Biology, Science for Life Laboratory, Uppsala University, SE- 14 75123, Uppsala, Sweden 15 4 Department for Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of California, Berkeley, USA 16 17 *to whom the correspondence should be addressed: 18 Alexander J. Probst 19 University of Duisburg-Essen 20 Universitätsstrasse 4 21 45141 Essen 22 [email protected] 23 24 25 Content: 26 1. Supplementary Methods 27 2. Supplementary Tables 28 3. Supplementary Figure 29 4. References 30 31 32 33 1. Supplementary methods 34 Phylogenetic analysis 35 Hmm profiles of the 37 maker genes used by the phylosift v1.01 software [1, 2] were queried 36 against a representative set of archaeal genomes from NCBI (182) and the GOLD database (3) as 37 well as against the huberarchaeal population genome (for details on genomes please see 38 Supplementary Data file 1) using the phylosift search mode [1, 2]. Protein sequences 39 corresponding to each of the maker genes were subsequently aligned using mafft-linsi v7.407 [3] 40 and trimmed with BMGE-1.12 (parameters: -t AA -m BLOSUM30 -h 0.55) [4]. -

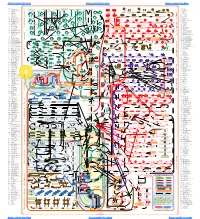

O O2 Enzymes Available from Sigma Enzymes Available from Sigma

COO 2.7.1.15 Ribokinase OXIDOREDUCTASES CONH2 COO 2.7.1.16 Ribulokinase 1.1.1.1 Alcohol dehydrogenase BLOOD GROUP + O O + O O 1.1.1.3 Homoserine dehydrogenase HYALURONIC ACID DERMATAN ALGINATES O-ANTIGENS STARCH GLYCOGEN CH COO N COO 2.7.1.17 Xylulokinase P GLYCOPROTEINS SUBSTANCES 2 OH N + COO 1.1.1.8 Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase Ribose -O - P - O - P - O- Adenosine(P) Ribose - O - P - O - P - O -Adenosine NICOTINATE 2.7.1.19 Phosphoribulokinase GANGLIOSIDES PEPTIDO- CH OH CH OH N 1 + COO 1.1.1.9 D-Xylulose reductase 2 2 NH .2.1 2.7.1.24 Dephospho-CoA kinase O CHITIN CHONDROITIN PECTIN INULIN CELLULOSE O O NH O O O O Ribose- P 2.4 N N RP 1.1.1.10 l-Xylulose reductase MUCINS GLYCAN 6.3.5.1 2.7.7.18 2.7.1.25 Adenylylsulfate kinase CH2OH HO Indoleacetate Indoxyl + 1.1.1.14 l-Iditol dehydrogenase L O O O Desamino-NAD Nicotinate- Quinolinate- A 2.7.1.28 Triokinase O O 1.1.1.132 HO (Auxin) NAD(P) 6.3.1.5 2.4.2.19 1.1.1.19 Glucuronate reductase CHOH - 2.4.1.68 CH3 OH OH OH nucleotide 2.7.1.30 Glycerol kinase Y - COO nucleotide 2.7.1.31 Glycerate kinase 1.1.1.21 Aldehyde reductase AcNH CHOH COO 6.3.2.7-10 2.4.1.69 O 1.2.3.7 2.4.2.19 R OPPT OH OH + 1.1.1.22 UDPglucose dehydrogenase 2.4.99.7 HO O OPPU HO 2.7.1.32 Choline kinase S CH2OH 6.3.2.13 OH OPPU CH HO CH2CH(NH3)COO HO CH CH NH HO CH2CH2NHCOCH3 CH O CH CH NHCOCH COO 1.1.1.23 Histidinol dehydrogenase OPC 2.4.1.17 3 2.4.1.29 CH CHO 2 2 2 3 2 2 3 O 2.7.1.33 Pantothenate kinase CH3CH NHAC OH OH OH LACTOSE 2 COO 1.1.1.25 Shikimate dehydrogenase A HO HO OPPG CH OH 2.7.1.34 Pantetheine kinase UDP- TDP-Rhamnose 2 NH NH NH NH N M 2.7.1.36 Mevalonate kinase 1.1.1.27 Lactate dehydrogenase HO COO- GDP- 2.4.1.21 O NH NH 4.1.1.28 2.3.1.5 2.1.1.4 1.1.1.29 Glycerate dehydrogenase C UDP-N-Ac-Muramate Iduronate OH 2.4.1.1 2.4.1.11 HO 5-Hydroxy- 5-Hydroxytryptamine N-Acetyl-serotonin N-Acetyl-5-O-methyl-serotonin Quinolinate 2.7.1.39 Homoserine kinase Mannuronate CH3 etc. -

REGULATION of MAIZE (Zea Mays L.) STARCH SYNTHASE Iia by PROTEIN PHOSPHORYLATION

Regulation of Maize (Zea mays L.) Starch Synthase IIa by Protein Phosphorylation by Usha P. Rayirath A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfillment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Molecular and Cellular Biology Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Usha P. Rayirath, May, 2014 ABSTRACT REGULATION OF MAIZE (Zea mays L.) STARCH SYNTHASE IIa BY PROTEIN PHOSPHORYLATION Usha P. Rayirath Advisor: Dr. Michael J. Emes University of Guelph, 2014 Starch is a significant carbohydrate reserve in plants and has enormous use in both food and non-food industries. Biosynthesis of storage starch in maize (Zea mays L.) occurs in the amyloplasts of the developing endosperm, through the coordinated actions of several enzymes, including ADP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (AGPase), starch synthases (SS), starch branching enzymes (SBE) and debranching enzymes (DBE). Starch synthase IIa (SSIIa) catalyzes the synthesis of intermediate glucan chains (DP 12- 25) and plays a significant role in starch biosynthesis. Previous studies indicate that in cereal endosperm, protein phosphorylation plays a major role in regulating the formation of functional multi-enzyme complexes between SSs and SBEs during starch biosynthesis and that SSIIa forms the core of such a functional protein complex, with SSI and SBEIIb. The present study investigated the specific role of protein phosphorylation on the regulation of SSIIa, in the amyloplasts of developing maize endosperm, during starch biosynthesis. In vitro phosphorylation of stromal SSIIa in maize amyloplasts was detected by phosphate affinity Mn2+ Phos-tagTM gel electrophoresis, Pro-Q® Diamond phospho-protein gel staining, and by autoradiography following radio labelling with γ- [32-P] ATP. -

The Analysis of Global Gene Expression Related to Starch, Lipid and Protein Composition

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2006 The na alysis of global gene expression related to starch, lipid and protein composition Ling Li Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Genetics Commons, and the Molecular Biology Commons Recommended Citation Li, Ling, "The na alysis of global gene expression related to starch, lipid and protein composition " (2006). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 1864. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/1864 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The analysis of global gene expression related to starch, lipid and protein composition by Ling Li A dissertation submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Major: Genetics Program of Study Committee: Eve Syrkin Wurtele, Major Professor Martin H. Spalding Mark E. Westgate Dan S. Nettleton Martha G. James Basil J. Nikolau Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2006 Copyright © Ling Li, 2006. All rights reserved. UMI Number: 3243820 Copyright 2007 by Li, Ling All rights reserved. UMI Microform 3243820 Copyright 2007 by ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. This microform edition is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest Information and Learning Company 300 North Zeeb Road P.O.