Serrasalmus Rhombeus) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

13914444D46c0aa91d02e31218

2 Breeding of wild and some domestic animals at regional zoological institutions in 2013 3 РЫБЫ P I S C E S ВОББЕЛОНГООБРАЗНЫЕ ORECTOLOBIFORMES Сем. Азиатские кошачьи акулы (Бамбуковые акулы) – Hemiscyllidae Коричневополосая бамбуковая акула – Chiloscyllium punctatum Brownbanded bambooshark IUCN (NT) Sevastopol 20 ХВОСТОКОЛООБРАЗНЫЕ DASYATIFORMES Сем. Речные хвостоколы – Potamotrygonidae Глазчатый хвостокол (Моторо) – Potamotrygon motoro IUCN (DD) Ocellate river stingray Sevastopol - ? КАРПООБРАЗНЫЕ CYPRINIFORMES Сем. Цитариновые – Citharinidae Серебристый дистиход – Distichodusaffinis (noboli) Silver distichodus Novosibirsk 40 Сем. Пираньевые – Serrasalmidae Серебристый метиннис – Metynnis argenteus Silver dollar Yaroslavl 10 Обыкновенный метиннис – Metynnis schreitmuelleri (hypsauchen) Plainsilver dollar Nikolaev 4; Novosibirsk 100; Kharkov 20 Пятнистый метиннис – Metynnis maculatus Spotted metynnis Novosibirsk 50 Пиранья Наттерера – Serrasalmus nattereri Red piranha Novosibirsk 80; Kharkov 30 4 Сем. Харацидовые – Characidae Красноплавничный афиохаракс – Aphyocharax anisitsi (rubripinnis) Bloodfin tetra Киев 5; Perm 10 Парагвайский афиохаракс – Aphyocharax paraquayensis Whitespot tetra Perm 11 Рубиновый афиохаракс Рэтбина – Aphyocharax rathbuni Redflank bloodfin Perm 10 Эквадорская тетра – Astyanax sp. Tetra Perm 17 Слепая рыбка – Astyanax fasciatus mexicanus (Anoptichthys jordani) Mexican tetra Kharkov 10 Рублик-монетка – Ctenobrycon spilurus (+ С. spilurusvar. albino) Silver tetra Kharkov 20 Тернеция (Траурная тетра) – Gymnocorymbus -

Serrasalmus Geryi Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Serrasalmus geryi (a piranha, no common name) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, April 2012 Revised, July 2018 Web Version, 8/22/2019 Photo: greyloch. Licensed under Creative Commons BY-NC-ND 2.0. Available: https://www.flickr.com/photos/greyloch/26981441525. (July 2018). 1 Native Range and Status in the United States Native Range From Froese and Pauly (2018): “South America: Tocantins River Basin in Brazil.” 1 Status in the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the wild in the United States. This species is in trade in the United States. For example: From AquaScapeOnline (2018): “Violet Line Piranha 4"-6" (Serrasalmus Geryi [sic]) […] Special $300.00 Reg. Price $400.00” Possession or importation of fish of the genus Serrasalmus, or fish known as “piranha” in general, is banned or regulated in many States. Every effort has been made to list all applicable State laws and regulations pertaining to this species, but this list may not be comprehensive. From Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (2019): “No person, firm, corporation, partnership, or association shall possess, sell, offer for sale, import, bring, release or cause to be brought or imported into the State of Alabama any of the following live fish or animals: […] Any Piranha or any fish of the genera Serrasalmus, Pristobrycon, Pygocentrus, Catorprion, or Pygopristus; […]” From Alaska State Legislature (2019): “Except as provided in (b) - (d) of this section, no person may import any live fish into the state for purposes of stocking or rearing in the waters of the state. -

Freshwater Ornamental Fish Commonly Cultured in Florida 1 Jeffrey E

Circular 54 Freshwater Ornamental Fish Commonly Cultured in Florida 1 Jeffrey E. Hill and Roy P.E. Yanong2 Introduction Unlike many traditional agriculture industries in Florida which may raise one or only a few different species, tropical Freshwater tropical ornamental fish culture is the largest fish farmers collectively culture hundreds of different component of aquaculture in the State of Florida and ac- species and varieties of fishes from numerous families and counts for approximately 95% of all ornamentals produced several geographic regions. There is much variation within in the US. There are about 200 Florida producers who and among fish groups with regard to acceptable water collectively raise over 800 varieties of freshwater fishes. In quality parameters, feeding and nutrition, and mode of 2003 alone, farm-gate value of Florida-raised tropical fish reproduction. Some farms specialize in one or a few fish was about US$47.2 million. Given the additional economic groups, while other farms produce a wide spectrum of effects of tropical fish trade such as support industries, aquatic livestock. wholesalers, retail pet stores, and aquarium product manufacturing, the importance to Florida is tremendous. Fish can be grouped in a number of different ways. One major division in the industry which has practical signifi- Florida’s tropical ornamental aquaculture industry is cance is that between egg-laying species and live-bearing concentrated in Hillsborough, Polk, and Miami-Dade species. The culture practices for each division are different, counties with additional farms throughout the southern requiring specialized knowledge and equipment to succeed. half of the state. Historic factors, warm climate, the proxim- ity to airports and other infrastructural considerations This publication briefly reviews the more common groups (ready access to aquaculture equipment, supplies, feed, etc.) of freshwater tropical ornamental fishes cultured in Florida are the major reasons for this distribution. -

Serrasalmus Elongatus (Slender Piranha) Ecological Risk Screening Summary

Slender Piranha (Serrasalmus elongatus) Ecological Risk Screening Summary U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, April 2012 Revised, July 2018 and August 2019 Web Version, 8/21/2019 Photo: Clinton & Charles Robertson. Licensed under Creative Commons BY 2.0. Available: https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=16042555. (July 2018). 1 Native Range and Status in the United States 1 Native Range From Eschmeyer et al. (2018): “Amazon and Orinoco River basins: Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela.” Status in the United States This species has not been reported as introduced or established in the wild in the United States. This species is in trade in the United States, for example: From AquaScapeOnline (2018): “Elongatus Piranha 5"-6" (Serrasalmus Elongatus [sic]) […] Our Price: $125.00” “Elongatus black mask 6"-7" (Serrasalmus Elongatus [sic]) […] Our Price: $150.00” Possession or importation of fish of the genus Serrasalmus, or fish known as “piranha” in general, is banned or regulated in many States. Every effort has been made to list all applicable State laws and regulations pertaining to this species, but this list may not be comprehensive. From Alabama Department of Conservation and Natural Resources (2019): “No person, firm, corporation, partnership, or association shall possess, sell, offer for sale, import, bring, release or cause to be brought or imported into the State of Alabama any of the following live fish or animals: […] Any Piranha or any fish of the genera Serrasalmus, Pristobrycon, Pygocentrus, Catorprion, or Pygopristus; […]” From Alaska State Legislature (2019): “Except as provided in (b) - (d) of this section, no person may import any live fish into the state for purposes of stocking or rearing in the waters of the state. -

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S

Summary Report of Freshwater Nonindigenous Aquatic Species in U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 4—An Update April 2013 Prepared by: Pam L. Fuller, Amy J. Benson, and Matthew J. Cannister U.S. Geological Survey Southeast Ecological Science Center Gainesville, Florida Prepared for: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Southeast Region Atlanta, Georgia Cover Photos: Silver Carp, Hypophthalmichthys molitrix – Auburn University Giant Applesnail, Pomacea maculata – David Knott Straightedge Crayfish, Procambarus hayi – U.S. Forest Service i Table of Contents Table of Contents ...................................................................................................................................... ii List of Figures ............................................................................................................................................ v List of Tables ............................................................................................................................................ vi INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................................. 1 Overview of Region 4 Introductions Since 2000 ....................................................................................... 1 Format of Species Accounts ...................................................................................................................... 2 Explanation of Maps ................................................................................................................................ -

Translocation of Trapped Bolivian River Dolphins (Inia Boliviensis)

J. CETACEAN RES. MANAGE. 21: 17–23, 2020 17 Translocation of trapped Bolivian river dolphins (Inia boliviensis) ENZO ALIAGA-ROSSEL1,3AND MARIANA ESCOBAR-WW2 Contact e-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT The Bolivian river dolphin, locally known as the bufeo, is the only cetacean in land-locked Bolivia. Knowledge about its conservation status and vulnerability to anthropogenic actions is extremely deficient. We report on the rescue and translocation of 26 Bolivian river dolphins trapped in a shrinking segment of the Pailas River, Santa Cruz, Bolivia. Several institutions, authorities and volunteers collaborated to translocate the dolphins, which included calves, juveniles, and pregnant females. The dolphins were successfully released into the Río Grande. Each dolphin was accompanied by biologists who assured their welfare. No detectable injuries occurred and none of the dolphins died during this process. If habitat degradation continues, it is likely that events in which river dolphins become trapped in South America may happen more frequently in the future. KEYWORDS: BOLIVIAN RIVER DOLPHIN; HABITAT DEGRADATION; CONSERVATION; STRANDINGS; TRANSLOCATION; SOUTH AMERICA INTRODUCTION distinct species, geographically isolated from the boto or Small cetaceans are facing several threats from direct or Amazon River dolphin (I. geoffrensis) (Gravena et al., 2014; indirect human impacts (Reeves et al., 2000). The pressure Ruiz-Garcia et al., 2008). This species has been categorised on South American and Asian river dolphins is increasing; by the Red Book of Wildlife Vertebrates of Bolivia as evidently, different river systems have very different problems. Vulnerable (VU), highlighting the need to conserve and Habitat degradation, dam construction, modification of river protect them from existing threats (Aguirre et al., 2009). -

Summary of Temperature Metrics for Aquatic Invasive Fish Species in the Prairie Region

Summary of Temperature Metrics for Aquatic Invasive Fish Species in the Prairie Region Theresa E. Mackey, Caleb T. Hasler, and Eva C. Enders Fisheries and Oceans Canada Ecosystems and Oceans Science Central and Arctic Region Freshwater Institute Winnipeg, MB R3T 2N6 2019 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 3308 1 Canadian Technical Report of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences Technical reports contain scientific and technical information that contributes to existing knowledge but which is not normally appropriate for primary literature. Technical reports are directed primarily toward a worldwide audience and have an international distribution. No restriction is placed on subject matter and the series reflects the broad interests and policies of Fisheries and Oceans Canada, namely, fisheries and aquatic sciences. Technical reports may be cited as full publications. The correct citation appears above the abstract of each report. Each report is abstracted in the data base Aquatic Sciences and Fisheries Abstracts. Technical reports are produced regionally but are numbered nationally. Requests for individual reports will be filled by the issuing establishment listed on the front cover and title page. Numbers 1-456 in this series were issued as Technical Reports of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. Numbers 457-714 were issued as Department of the Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service, Research and Development Directorate Technical Reports. Numbers 715-924 were issued as Department of Fisheries and Environment, Fisheries and Marine Service Technical Reports. The current series name was changed with report number 925. Rapport technique canadien des sciences halieutiques et aquatiques Les rapports techniques contiennent des renseignements scientifiques et techniques qui constituent une contribution aux connaissances actuelles, mais qui ne sont pas normalement appropriés pour la publication dans un journal scientifique. -

Caudal Fin-Nipping by Serrasalmus Maculatus (Characiformes: Serrasalmidae) in a Small Water Reservoir: Seasonal Variation and Prey Selection

ZOOLOGIA 32 (6): 457–462, December 2015 http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-46702015000600004 Caudal fin-nipping by Serrasalmus maculatus (Characiformes: Serrasalmidae) in a small water reservoir: seasonal variation and prey selection André T. da Silva1,*, Juliana Zina2, Fabio C. Ferreira3, Leandro M. Gomiero1 & Roberto Goitein1 1Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de Biociências, Universidade Estadual Paulista. Avenida 24A, 1515, Bela Vista, 13506-900 Rio Claro, SP, Brazil. 2Departamento de Ciências Biológicas, Universidade Estadual do Sudoeste da Bahia. Rua José Moreira Sobrinho, 45206-000 Jequié, BA, Brazil. 3Departamento de Ciências do Mar, Universidade Federal de São Paulo. Rua Silva Jardim, 136, Edifício Central, 11015-020 Santos, SP, Brazil. *Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT. We evaluated how seasonality affects the frequency and intensity of fin-nipping, as well as the fish prey preferences of Serrasalmus maculatus Kner, 1858. The study took place in a small reservoir of the Ribeirão Claro River basin, state of São Paulo, southeastern Brazil. Fish were sampled monthly from July 2003 to June 2004, using gillnets. Sampling consisted of leaving 50 m of gillnets in the water for approximately 24 hours each month. No seasonal variation in the frequency and intensity of fin-nipping was observed. Among six prey species, piranhas displayed less damage in their fins, possibly due to intraspecific recognition. Under natural conditions, the caudal fins of Cyphocharax modestus (Fernández- Yépez, 1948) were the most intensively mutilated, which suggests multiple attacks on the same individual. The size of individuals in this species was positively correlated with the mutilated area of the fin, whereas no such correlation was observed for Astyanax altiparanae Garutti & Britski, 2000 and Acestrorhynchus lacustris (Lütken, 1875). -

Host-Parasite Interactions Between the Piranha Pygocentrus Nattereri

Neotropical Ichthyology, 2(2):93-98, 2004 Copyright © 2004 Sociedade Brasileira de Ictiologia Host-parasite interactions between the piranha Pygocentrus nattereri (Characiformes: Characidae) and isopods and branchiurans (Crustacea) in the rio Araguaia basin, Brazil Lucélia Nobre Carvalho*, ***, Rafael Arruda**, *** and Kleber Del-Claro*** In the tropics, studies on the ecology of host-parasite interactions are incipient and generally related to taxonomic aspects. The main objective of the present work was to analyze ecological aspects and identify the metazoan fauna of ectoparasites that infest the piranha, Pygocentrus nattereri. In May 2002, field samples were collected in the rio Araguaia basin, State of Goiás (Brazil). A total of 252 individuals of P. nattereri were caught with fishhooks and 32.14% were infested with ectoparasite crustaceans. The recorded ectoparasites were branchiurans, Argulus sp. and Dolops carvalhoi and the isopods Braga patagonica, Anphira branchialis and Asotana sp. The prevalence and mean intensity of branchiurans (16.6% and 1.5, respectively) and isopods (15.5% and 1.0, respectively) were similar. Isopods were observed in the gills of the host; branchiurans were more frequent where the skin was thinner, and facilitated attachment and feeding. The ventral area, the base of the pectoral fin and the gular area were the most infested areas. The correlations between the standard length of the host and the variables intensity and prevalence of crustaceans parasitism, were significant only for branchiurans (rs = 0.2397, p = 0.0001; χ2 = 7.97; C = 0.19). These results suggest that both feeding sites and body size probably play an important role in the distribution and abundance of ectoparasites. -

Zootaxa, Notarius (Siluriformes: Ariidae)

Zootaxa 1249: 47–59 (2006) ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) www.mapress.com/zootaxa/ ZOOTAXA 1249 Copyright © 2006 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) A new species of Notarius (Siluriformes: Ariidae) from the Colombian Pacific RICARDO BETANCUR-R.1 & ARTURO ACERO P.2 1Department of Biological Sciences, Auburn University, 331 Funchess Hall, Auburn, AL 36849, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 2Universidad Nacional de Colombia (Instituto de Ciencias Naturales), Cerro Punta Betín, A.A. 1016 (INVEMAR), Santa Marta, Colombia. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Notarius armbrusteri n. sp. is described from specimens purchased in the fish market of Buenaventura, Valle del Cauca, Colombia. The species is distinguished from other eastern Pacific species of Notarius by the following combination of features: mouth small, width 11.1–11.8% SL; eye large, diameter 4.3–4.9% SL; distance between anterior nostrils 6.1–6.9% SL, distance between posterior nostrils 5.9–6.9% SL; short maxillary barbels, length 20.5–22.2% SL; and gill rakers on first arch 3–4+8–9 (total 11–13). Based on mitochondrial evidence (cytochrome b and ATP synthase 8/6, total 1937 base pairs), the new species is closely related to N. insculptus, from the Pacific Panama. An updated key to identify the eight described species of Notarius from the eastern Pacific is provided. Key words: Notarius armbrusteri n. sp., Ariidae, sea catfishes, eastern Pacific Introduction The amphiamerican sea catfish genus Notarius Gill was recently revised by Betancur-R. and Acero P. (2004). Notarius includes at least 14 species, with seven distributed in the eastern Pacific (EP). -

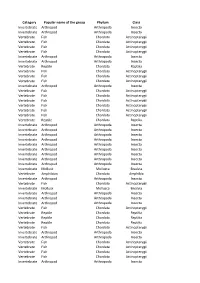

Category Popular Name of the Group Phylum Class Invertebrate

Category Popular name of the group Phylum Class Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Vertebrate Reptile Chordata Reptilia Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Vertebrate Reptile Chordata Reptilia Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Mollusk Mollusca Bivalvia Vertebrate Amphibian Chordata Amphibia Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Vertebrate Fish Chordata Actinopterygii Invertebrate Mollusk Mollusca Bivalvia Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Invertebrate Arthropod Arthropoda Insecta Vertebrate -

Reproductive Characteristics of Characid Fish Species (Teleostei

Reproductive characteristics of characid fish species (Teleostei... 469 Reproductive characteristics of characid fish species (Teleostei, Characiformes) and their relationship with body size and phylogeny Marco A. Azevedo Setor de Ictiologia, Museu de Ciências Naturais, Fundação Zoobotânica do Rio Grande do Sul, Rua Dr. Salvador França, 1427, 90690-000 Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil. ([email protected]) ABSTRACT. In this study, I investigated the reproductive biology of fish species from the family Characidae of the order Characiformes. I also investigated the relationship between reproductive biology and body weight and interpreted this relationship in a phylogenetic context. The results of the present study contribute to the understanding of the evolution of the reproductive strategies present in the species of this family. Most larger characid species and other characiforms exhibit a reproductive pattern that is generally characterized by a short seasonal reproductive period that lasts one to three months, between September and April. This is accompanied by total spawning, an extremely high fecundity, and, in many species, a reproductive migration. Many species with lower fecundity exhibit some form of parental care. Although reduction in body size may represent an adaptive advantage, it may also require evolutionary responses to new biological problems that arise. In terms of reproduction, smaller species have a tendency to reduce the number of oocytes that they produce. Many small characids have a reproductive pattern similar to that of larger characiforms. On the other hand they may also exhibit a range of modifications that possibly relate to the decrease in body size and the consequent reduction in fecundity.