World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace Sculptures of Abomey

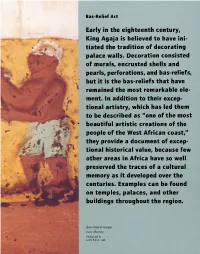

Bas-Relief Art Early in the eighteenth century, King Agaja is believed to have ini tiated the tradition of decorating palace walls. Decoration consisted of murals, encrusted shells and pearls, perfo rations, and bas-reliefs, , but it is the bas-reliefs that have remained the most remarkable ele ment. In addition to their excep tional artistry, which has led them to be described as "one of the most " beautiful artistic creations of the people of the West African coast, rr they provide a document of excep tional historical value, because few other areas in Africa have so well preserved the traces of a cultural · . memory as it developed over the centuries. Exa mples can be found on temples, palaces, and other buildings throughout the region. Bas-relief at temple near Abomey. Photograph by Leslie Railler, 1996. BAS-RELIEF ART 49 Commonly called noudide in Fon, from the root word meaning "to design" or "to portray," the bas-reliefs are three-dimensional, modeled- and painted earth pictograms. Early examples of the form, first in religious temples and then in the palaces, were more abstract than figurative. Gradually, figurative depictions became the prevalent style, illustrating the tales told by the kings' heralds and other Fon storytellers. Palace bas-reliefs were fashioned according to a long-standing tradition of The original earth architectural and sculptural renovation. used to make bas Ruling monarchs commissioned new palaces reliefs came from ter and artworks, as well as alterations of ear mite mounds such as lier ones, thereby glorifying the past while this one near Abomey. bringing its art and architecture up to date. -

S a Rd in Ia

M. Mandarino/Istituto Euromediterraneo, Tempio Pausania (Sardinia) Land07-1Book 1.indb 97 12-07-2007 16:30:59 Demarcation conflicts within and between communities in Benin: identity withdrawals and contested co-existence African urban development policy in the 1990s focused on raising municipal income from land. Population growth and a neoliberal environment weakened the control of clans and lineages over urban land ownership to the advantage of individuals, but without eradicating the importance of personal relationships in land transactions or of clans and lineages in the political structuring of urban space. The result, especially in rural peripheries, has been an increase in land aspirations and disputes and in their social costs, even in districts with the same territorial control and/or the same lines of nobility. Some authors view this simply as land “problems” and not as conflicts pitting locals against outsiders and degenerating into outright clashes. However, decentralization gives new dimensions to such problems and is the backdrop for clashes between differing perceptions of territorial control. This article looks at the ethnographic features of some of these clashes in the Dahoman historic region of lower Benin, where boundaries are disputed in a context of poorly managed urban development. Such disputes stem from land registries of the previous but surviving royal administration, against which the fragile institutions of the modern state seem to be poorly equipped. More than a simple problem of land tenure, these disputes express an internal rejection of the legitimacy of the state to engage in spatial structuring based on an ideal of co-existence; a contestation that is put forward with the de facto complicity of those acting on behalf of the state. -

Monographie Des Communes Des Départements De L'atlantique Et Du Li

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des communes des départements de l’Atlantique et du Littoral Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes Monographie départementale _ Mission de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin _ 2019 1 Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Monographie départementale _ Mission de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin _ 2019 2 Tables des matières LISTE DES CARTES ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS DE L’ATLANTIQUE ET DU LITTORAL ................................................ 7 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LE DEPARTEMENT DE L’ATLANTIQUE ........................................................................................ 7 1.1.1.1. Présentation du Département de l’Atlantique ...................................................................................... -

Water Supply and Waterbornes Diseases in the Population of Za- Kpota Commune (Benin, West Africa)

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention (IJESI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ||Volume 7 Issue 6 Ver II || June 2018 || PP 33-39 Water Supply and Waterbornes Diseases in the Population of Za- Kpota Commune (Benin, West Africa) Léocadie Odoulami, Brice S. Dansou & Nadège Kpoha Laboratoire Pierre PAGNEY, Climat, Eau, Ecosystème et Développement LACEEDE)/DGAT/FLASH/ Université d’Abomey-Calavi (UAC). 03BP: 1122 Cotonou, République du Bénin (Afrique de l’Ouest) Corresponding Auther: Léocadie Odoulami Summary :The population of the common Za-kpota is subjected to several difficulties bound at the access to the drinking water. This survey aims to identify and to analyze the problems of provision in drinking water and the risks on the human health in the township of Za-kpota. The data on the sources of provision in drinking water in the locality, the hydraulic infrastructures and the state of health of the populations of 2000 to 2012 have been collected then completed by information gotten by selected 198 households while taking into account the provision difficulties in water of consumption in the households. The analysis of the results gotten watch that 43 % of the investigation households consume the water of well, 47 % the water of cistern, 6 % the water of boring, 3% the water of the Soneb and 1% the water of marsh. However, the physic-chemical and bacteriological analyses of 11 samples of water of well and boring revealed that the physic-chemical and bacteriological parameters are superior to the norms admitted by Benin. The consumption of these waters exposes the health of the populations to the water illnesses as the gastroenteritis, the diarrheas, the affections dermatologic,.. -

Monographie Des Départements Du Zou Et Des Collines

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des départements du Zou et des Collines Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes du département de Zou Collines Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Tables des matières 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LE DEPARTEMENT ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS ZOU-COLLINES ...................................................................................... 6 1.1.1.1. Aperçu du département du Zou .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. GRAPHIQUE 1: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DU ZOU ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1.2. Aperçu du département des Collines .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2. GRAPHIQUE 2: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES .................................................................................... 10 1.1.2. -

Rapport Définitif De La Sélection Des 70 Formations Sanitaires (FS) Témoins Pour Les FS Du Projet FBR Du Bénin Par Joseph FLENON, Consultant

Rapport définitif de la sélection des 70 formations sanitaires (FS) témoins pour les FS du Projet FBR du Bénin par Joseph FLENON, Consultant. Dans la première partie du point n°1 de ce contrat en cours d’exécution, j’ai sélectionné de manière aléatoire simple 8 Zones Sanitaires (ZS) témoins (au lieu de 5 ou 6) pour les 8 ZS du projet FBR du Bénin et j’en ai fait un rapport Dans cette deuxième partie du point n°1, j’ai procédé à la sélection de 70 formations sanitaire (FS) dans 10 ZS témoins (au lieu de 8ZS témoins) car suivant les critères de sélection de ces FS, les 8ZS sélectionnées dans la première partie du point n°1, m’ont permis de sélectionner à leur tour 47 FS témoins au lieu de 70 FS témoins. La Sélection aléatoire simple d’une ZS contrôle dans chacun des 8 listes a donné les 8 ZS contrôles suivantes : 1.ZS Bohicon-Zakpota-Zogbodomey : ZS contrôle : ZS Djidja-Abomey-Agbangnizoun 2.ZS Covè-Ouinhi-Zangnanado : ZS contrôle : ZS Pobè-Ketou-Adja-Ouèrè 3.ZS Lokossa-Athiémé : ZS contrôle : ZS Aplahoué-Djakotomè-Dogbo 4.ZS Ouidah-Kpomassè-Tori-Bossito : ZS contrôle : ZS Allada-Toffo-Zê 5.ZS Porto-Novo-Aguégués-Sèmè-Podji : ZS contrôle : ZS Cotonou 6 6.ZS Adjohoun-Bonou-Dangbo : ZS contrôle : ZS Abomey-Calavi-Sô-Ava 7.ZS Banikoara : ZS contrôle : ZS Kandi-Gogounou-Ségbana 8.ZS Kouandé-Ouassa-Péhunco-Kérou : ZS contrôle : ZS Tanguiéta-Cobly-Matéri Les critères de sélections des FS témoins proposés dans les TDR peuvent être classés en critères exclusifs (être à moins de 15 km de la frontière d’une ZS du Projet FBR et avoir moins de 2 personnels qualifiés) et en critères non exclusifs (certaines FS témoins doivent avoir au moins 15 CPN par jour). -

Paper Download

ECAS 2017 #BidoungChallenge in Cameroon ■ Profile ■ 1972: Born in Osaka, Japan 1994-96: Japanese Embassy to Senegal Political impact of 2000-01:University of Bordeaux (Science Po) 2003: Ph.D. in Political Science (Kobe University, Japan) 2011-12: Centre Emile Durkheim, IEP Bordeaux (Visiting fellow) decentralization 2013- : Associate Prof at Ritsumeikan University, Japan in urbanizing Africa ◆Research subjects (African politics & Int’l relations): Democratization, Decentralization , Power & Symbol, Witchcraft July 1, 2017 and politics, Asia-Africa relations, African studies in Asian countries, Border, Local govt’s int’l cooperation , SNS in Politics, Takuo IWATA Laughter in politics, Eating acts (manducation) in politics etc. (Ritsumeikan Univ, Kyoto, Japan) ◆Field work area: West Africa ( Benin , Burkina Faso , Togo, [email protected] occasionally Ghana, Mali), Asian countries 1 2 Source: Journal du Jeudi (No.1289, June 2-8, 2016) Source: Africa Daily News (@AfricaDNews, Feb 8, 2017) ■ Today’s content ■ 1. Introduction 1. Introduction 1-1. Research question ◆ How decentralization & urbanization affect local political 2. Decentralization Process in African Countries power balance, then national politics in African countries (with[out] ongoing democratization process)? 3. Political Impact of Decentralization 1-2. Research approach & objective 4. Development of Decentralized Cooperation ◆ Focusing on politics in urban local governments ( communes ) 5. Political Turbulences in Decentralizing 1-3. Research topic Local Governance ◆ Politicizing local governance in decentralization reform ◆ Decentralization in urban Africa, decentralized cooperation 6. Conclusion (local diplomacy), Storm of discharges of Mayors ◆ Case studies in Benin & Burkina Faso 3 4 InterviewSource: with Journal Mayor du Jeudi of Abomey (Burkina (Benin)Faso), No.959, [October February 2005, 4-10, 2010.Cotonou] 2. -

Evaluation Design Report for the Benin Power Compact's Electricity Generation Project and Electricity Distribution Project

FINAL REPORT Evaluation Design Report for the Benin Power Compact's Electricity Generation Project and Electricity Distribution Project March 7, 2018 Christopher Ksoll Kristine Bos Arif Mamun Anthony Harris Sarah Hughes Submitted to: Millennium Challenge Corporation 1099 14th Street, NW Suite 700 Washington, DC 20005 Project Monitor: Hamissou Samari Contract Number: MCC-16-CON-0058 Submitted by: Mathematica Policy Research 1100 1st Street, NE, 12th Floor Washington, DC 20002-4221 Telephone: (202) 484-9220 Facsimile: (202) 863-1763 Project Director: Sarah Hughes Reference Number: 50339.01.200.031.000 This page has been left blank for double-sided copying. BENIN ENERGY II: EVALUATION DESIGN REPORT MATHEMATICA POLICY RESEARCH CONTENTS ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... VII I. INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................ 1 II. OVERVIEW OF THE COMPACT, GENERATION ACTIVITY, AND DISTRIBUTION ACTIVITY ......................................................................................................................................... 5 A. Overview of the Benin Power Compact ..................................................................................... 5 B. Overview of the theory of change .............................................................................................. 9 C. Economic rate of return and -

Just Like in Colonial Times? Administrative Practice and Local Reflections on ‘Grassroots Neocolonialism’ in Autonomous and Postcolonial Dahomey, –

Journal of African History, . (), pp. –. © Cambridge University Press . This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/./), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. doi:./S JUST LIKE IN COLONIAL TIMES? ADMINISTRATIVE PRACTICE AND LOCAL REFLECTIONS ON ‘GRASSROOTS NEOCOLONIALISM’ IN AUTONOMOUS AND POSTCOLONIAL DAHOMEY, – Alexander Keese University of Geneva* Abstract In Dahomey (Benin) during the period of autonomy and the first years of independence, the reference to a colonial past was an important instrument and point of debate. Members of a new group of politicians used it to accuse trade union leaders to make unrealistic claims; local peasants mobilized it as their point of reference against infrastruc- ture projects; officials discussed it to make sense of tax refusals, while locals invoked older forms of tax resistance they had practiced under colonial rule. This article follows the dif- ferent relationships with the colonial past, through the regions of Abomey and Porto- Novo, and shows how these experiences were viewed by local residents and by nationalist leaders, such as Justin Ahomadegbé. It also serves as an example and an injunction to make use of the administrative postcolonial archive. Key Words archives, decolonisation, development, labour, taxation. INTRODUCTION In August , a group of youth militia leaders in the southeastern city of Kétou in Benin made a striking claim; they branded the politicians and administrators in the town, includ- ing those installed after Mathieu Kérékou’s ‘revolution’, the coup d’état of ,as‘neo- colonialist’. -

International Journal of Advanced Engineering and Management Research Vol

International Journal of Advanced Engineering and Management Research Vol. 3 Issue 6; 2018 www.ijaemr.com ISSN: 2456-3676 DETERMINATION OF EXPLANATORY FACTORS OF THE DYNAMICS OF LAND OCCUPANCY IN THE COMMUNITY OF DJIDJA Brice SèvègniTCHAOU1, Calixte HOUSSOU1, José Edgard GNELE3et Odile DOSSOU GUEDEGBE1 Laboratoire d’Aménagement du Territoire, d’Environnement et de Développement Durable (LATEDD) / FLASH / Université d’Abomey-Calavi Université de Parakou Abstract The population explosion and the intensification of economic activities have led populations to occupy the land in different ways and for different reasons. The objective of the study is to determine the explanatory factors of the dynamics of the land occupation in the municipality of Djidja. The research methodology is based on data collection, manual and statistical processing of data and analysis of results. Surveys are made from 271 heads or representatives of households and resource persons. From this field work, it appears that the expansion of charcoal and firewood production activities is widespread throughout the municipality of Djidja. The total annual production of wood for the whole commune is 113 91, 2704 m³ of wood which corresponds to 50,889,515 kg equivalent of wood, or 175,203,222 tons of wood equivalent. The factors of land-use dynamics are natural, socio-economic and political. The evaluation of the dynamics of the land occupation in Djidja Commune in 1986, 2000 and 2016 revealed a regression of natural formations in favor of mosaics of fields and fallows and agglomerations even inside the two classified forests of Atcherigbe, Dan and the communal forest of Kolobi which practically no longer exists. -

(Buruli Ulcer) in Rural Hospital, Southern Benin, 1997–2001 Martine Debacker,* Julia Aguiar,† Christian Steunou,† Claude Zinsou,*† Wayne M

Mycobacterium ulcerans Disease (Buruli Ulcer) in Rural Hospital, Southern Benin, 1997–2001 Martine Debacker,* Julia Aguiar,† Christian Steunou,† Claude Zinsou,*† Wayne M. Meyers,‡ Augustin Guédénon,§ Janet T. Scott,* Michèle Dramaix,¶ and Françoise Portaels* Data from 1,700 patients living in southern Benin were Even though large numbers of patients have been collected at the Centre Sanitaire et Nutritionnel Gbemoten, reported, the epidemiology of BU remains obscure, even in Zagnanado, Benin, from 1997 through 2001. In the Zou disease-endemic countries. In 1997, a first report was pub- region in 1999, Buruli ulcer (BU) had a higher detection rate lished on 867 BU patients from the Republic of Benin (21.5/100,000) than leprosy (13.4/100,000) and tuberculo- (West Africa) for 1989–1996 (4). Our study covers the sis (20.0/100,000). More than 13% of the patients had osteomyelitis. Delay in seeking treatment declined from 4 ensuing 5 years (1997 to 2001), during which a collabora- months in 1989 to 1 month in 2001, and median hospital- tive project was initiated to improve detection and control ization time decreased from 9 months in 1989 to 1 month of BU. This study describes BU in Benin and presents in 2001. This reduction is attributed, in part, to implement- demographic trends and epidemiologic data from the four ing an international cooperation program, creating a nation- southern regions of Benin (Zou, Oueme, Mono, and al BU program, and making advances in patient care. Atlantique), as seen in a rural hospital in the Zou Region. uruli ulcer (BU), caused by Mycobacterium ulcerans, Patients and Methods Bis the third most common mycobacterial disease in Our observations are based on 1,700 consecutive humans after tuberculosis and leprosy (1). -

Local Agro-Ecological Condition-Based Food Resources to Promote Infant Food Security: a Case Study from Benin

Local agro-ecological condition-based food resources to promote infant food security: a case study from Benin Flora Josiane Chadare, Nadia Fanou Fogny, Yann Eméric Madode, Juvencio Odilon G. Ayosso, Sèwanou Hermann Honfo, Folachodé Pierre Polycarpe Food Security TheKayodé, Science, Sociology et and Economicsal. of Food Production and Access to Food ISSN 1876-4517 Food Sec. DOI 10.1007/s12571-018-0819-y 1 23 Your article is protected by copyright and all rights are held exclusively by Springer Nature B.V. and International Society for Plant Pathology. This e-offprint is for personal use only and shall not be self-archived in electronic repositories. If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”. 1 23 Author's personal copy Food Security https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-018-0819-y ORIGINAL PAPER Local agro-ecological condition-based food resources to promote infant food security: a case study from Benin Flora Josiane Chadare1,2 & Nadia Fanou Fogny1 & Yann Eméric Madode1 & Juvencio Odilon G. Ayosso1 & Sèwanou Hermann Honfo3 & Folachodé Pierre Polycarpe Kayodé1 & Anita Rachel Linnemann4 & Djidjoho Joseph Hounhouigan 1 Received: 7 July 2017 /Accepted: 19 June 2018 # Springer Nature B.V.