Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Illegal Activities From

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace Sculptures of Abomey

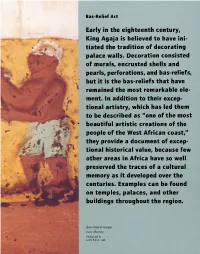

Bas-Relief Art Early in the eighteenth century, King Agaja is believed to have ini tiated the tradition of decorating palace walls. Decoration consisted of murals, encrusted shells and pearls, perfo rations, and bas-reliefs, , but it is the bas-reliefs that have remained the most remarkable ele ment. In addition to their excep tional artistry, which has led them to be described as "one of the most " beautiful artistic creations of the people of the West African coast, rr they provide a document of excep tional historical value, because few other areas in Africa have so well preserved the traces of a cultural · . memory as it developed over the centuries. Exa mples can be found on temples, palaces, and other buildings throughout the region. Bas-relief at temple near Abomey. Photograph by Leslie Railler, 1996. BAS-RELIEF ART 49 Commonly called noudide in Fon, from the root word meaning "to design" or "to portray," the bas-reliefs are three-dimensional, modeled- and painted earth pictograms. Early examples of the form, first in religious temples and then in the palaces, were more abstract than figurative. Gradually, figurative depictions became the prevalent style, illustrating the tales told by the kings' heralds and other Fon storytellers. Palace bas-reliefs were fashioned according to a long-standing tradition of The original earth architectural and sculptural renovation. used to make bas Ruling monarchs commissioned new palaces reliefs came from ter and artworks, as well as alterations of ear mite mounds such as lier ones, thereby glorifying the past while this one near Abomey. bringing its art and architecture up to date. -

Obtaining World Heritage Status and the Impacts of Listing Aa, Bart J.M

University of Groningen Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing Aa, Bart J.M. van der IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Aa, B. J. M. V. D. (2005). Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 Appendix 4 World heritage site nominations Listed site in May 2004 (year of rejection, year of listing, possible year of extension of the site) Rejected site and not listed until May 2004 (first year of rejection) Afghanistan Península Valdés (1999) Jam, -

S a Rd in Ia

M. Mandarino/Istituto Euromediterraneo, Tempio Pausania (Sardinia) Land07-1Book 1.indb 97 12-07-2007 16:30:59 Demarcation conflicts within and between communities in Benin: identity withdrawals and contested co-existence African urban development policy in the 1990s focused on raising municipal income from land. Population growth and a neoliberal environment weakened the control of clans and lineages over urban land ownership to the advantage of individuals, but without eradicating the importance of personal relationships in land transactions or of clans and lineages in the political structuring of urban space. The result, especially in rural peripheries, has been an increase in land aspirations and disputes and in their social costs, even in districts with the same territorial control and/or the same lines of nobility. Some authors view this simply as land “problems” and not as conflicts pitting locals against outsiders and degenerating into outright clashes. However, decentralization gives new dimensions to such problems and is the backdrop for clashes between differing perceptions of territorial control. This article looks at the ethnographic features of some of these clashes in the Dahoman historic region of lower Benin, where boundaries are disputed in a context of poorly managed urban development. Such disputes stem from land registries of the previous but surviving royal administration, against which the fragile institutions of the modern state seem to be poorly equipped. More than a simple problem of land tenure, these disputes express an internal rejection of the legitimacy of the state to engage in spatial structuring based on an ideal of co-existence; a contestation that is put forward with the de facto complicity of those acting on behalf of the state. -

Governance of Protected Areas from Understanding to Action

Governance of Protected Areas From understanding to action Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend, Nigel Dudley, Tilman Jaeger, Barbara Lassen, Neema Pathak Broome, Adrian Phillips and Trevor Sandwith Developing capacity for a protected planet Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No.20 IUCN WCPA’s BEST PRACTICE PROTECTED AREA GUIDELINES SERIES IUCN-WCPA’s Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines are the world’s authoritative resource for protected area managers. Involving collaboration among specialist practitioners dedicated to supporting better implementation in the field, they distil learning and advice drawn from across IUCN. Applied in the field, they are building institutional and individual capacity to manage protected area systems effectively, equitably and sustainably, and to cope with the myriad of challenges faced in practice. They also assist national governments, protected area agencies, non- governmental organisations, communities and private sector partners to meet their commitments and goals, and especially the Convention on Biological Diversity’s Programme of Work on Protected Areas. A full set of guidelines is available at: www.iucn.org/pa_guidelines Complementary resources are available at: www.cbd.int/protected/tools/ Contribute to developing capacity for a Protected Planet at: www.protectedplanet.net/ IUCN PROTECTED AREA DEFINITION, MANAGEMENT CATEGORIES AND GOVERNANCE TYPES IUCN defines a protected area as: A clearly defined geographical space, recognised, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, -

Big Cats in Africa Factsheet

INFORMATION BRIEF BIG CATS IN AFRICA AFRICAN LION (PANTHERA LEO) Famously known as the king of the jungle, the African lion is the second largest living species of the big cats, after the tiger. African lions are found mostly in savannah grasslands across many parts of sub-Saharan Africa but the “Babary lion” used to exist in the North of Africa including Tunisia, Morocco and Algeria, while the “Cape lion” existed in South Africa. Some lions have however been known to live in forests in Congo, Gabon or Ethiopia. Historically, lions used to live in the Mediterranean and the Middle East as well as in other parts of Asia such as India. While there are still some Asian Lions left in India, the African Lion is probably the largest remaining sub species of Lions in the world. They live in large groups called “prides”, usually made up of up to 15 lions. These prides consist of one or two males, and the rest females. The females are known for hunting for prey ranging from wildebeest, giraffe, impala, zebra, buffalo, rhinos, hippos, among others. The males are unique in appearance with the conspicuous mane around their necks. The mane is used for protection and intimidation during fights. Lions mate all year round, and the female gives birth to three or four cubs at a time, after a gestation period of close to 4 months (110 days). Lions are mainly threatened by hunting and persecution by humans. They are considered a threat to livestock, so ranchers usually shoot them or poison carcasses to keep them away from their livestock. -

Science in Africa: UNESCO's Contribution to Africa's Plan For

Contents Foreword 1 Biodiversity, Biotechnology and Indigenous Knowledge 2 Conservation and sustainable use of Information and Communication biodiversity 2 Technologies and Space Science and Technologies 15 Safe development and application of biotechnology 5 Information and communication technologies 15 Securing and using Africa’s indigenous knowledge 6 Establishing the African Institute of Space Science 17 Energy, Water and Desertification 7 Improving Policy Conditions and Building Building a sustainable energy base 7 Innovation Mechanisms 19 Securing and sustaining water 9 African Science, Technology and Innovation Indicators Initiative 19 Combating drought and desertification 12 Improving regional cooperation in science and technology 20 Building a public understanding of science and technology 23 Building science and technology policy capacity 25 Annexes 26 Annex I: Microbial Resource Centres in Africa 26 Annex II: UNESCO Chairs in Science and Technology in Africa 26 Annex III: World Heritage Sites in Africa 27 Annex IV: Biosphere Reserves in Africa 28 Published by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) with the support of the UK Permanent Delegation to UNESCO and UK Department for International Development Edited by Susan Schneegans and Anne Candau This brochure has been possible thanks to the contributions of UNESCO staff at Headquarters and in the field. Graphic design by Maro Haas Printed in France © UNESCO 2007 Download a copy from: www.unesco.org/science Request a copy from UNESCO: (Paris): [email protected]; [email protected] (Nairobi): [email protected] (Cairo): [email protected] Or write to: Mustafa El-Tayeb, Director, Division for Science Policy and Sustainable Development, Natural Sciences Sector, UNESCO, 1 rue Miollis, 75732 Paris Cédex 15, France Foreword Koïchiro Matsuura Director-General of UNESCO January 2007 The Year 2007 promises to be a year of great opportunity for science in Africa. -

Monographie Des Communes Des Départements De L'atlantique Et Du Li

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des communes des départements de l’Atlantique et du Littoral Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes Monographie départementale _ Mission de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin _ 2019 1 Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Monographie départementale _ Mission de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin _ 2019 2 Tables des matières LISTE DES CARTES ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS DE L’ATLANTIQUE ET DU LITTORAL ................................................ 7 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LE DEPARTEMENT DE L’ATLANTIQUE ........................................................................................ 7 1.1.1.1. Présentation du Département de l’Atlantique ...................................................................................... -

Water Supply and Waterbornes Diseases in the Population of Za- Kpota Commune (Benin, West Africa)

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention (IJESI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ||Volume 7 Issue 6 Ver II || June 2018 || PP 33-39 Water Supply and Waterbornes Diseases in the Population of Za- Kpota Commune (Benin, West Africa) Léocadie Odoulami, Brice S. Dansou & Nadège Kpoha Laboratoire Pierre PAGNEY, Climat, Eau, Ecosystème et Développement LACEEDE)/DGAT/FLASH/ Université d’Abomey-Calavi (UAC). 03BP: 1122 Cotonou, République du Bénin (Afrique de l’Ouest) Corresponding Auther: Léocadie Odoulami Summary :The population of the common Za-kpota is subjected to several difficulties bound at the access to the drinking water. This survey aims to identify and to analyze the problems of provision in drinking water and the risks on the human health in the township of Za-kpota. The data on the sources of provision in drinking water in the locality, the hydraulic infrastructures and the state of health of the populations of 2000 to 2012 have been collected then completed by information gotten by selected 198 households while taking into account the provision difficulties in water of consumption in the households. The analysis of the results gotten watch that 43 % of the investigation households consume the water of well, 47 % the water of cistern, 6 % the water of boring, 3% the water of the Soneb and 1% the water of marsh. However, the physic-chemical and bacteriological analyses of 11 samples of water of well and boring revealed that the physic-chemical and bacteriological parameters are superior to the norms admitted by Benin. The consumption of these waters exposes the health of the populations to the water illnesses as the gastroenteritis, the diarrheas, the affections dermatologic,.. -

Magnoliophyta, Arly National Park, Tapoa, Burkina Faso Pecies S 1 2, 3, 4* 1 3, 4 1

ISSN 1809-127X (online edition) © 2011 Check List and Authors Chec List Open Access | Freely available at www.checklist.org.br Journal of species lists and distribution Magnoliophyta, Arly National Park, Tapoa, Burkina Faso PECIES S 1 2, 3, 4* 1 3, 4 1 OF Oumarou Ouédraogo , Marco Schmidt , Adjima Thiombiano , Sita Guinko and Georg Zizka 2, 3, 4 ISTS L , Karen Hahn 1 Université de Ouagadougou, Laboratoire de Biologie et Ecologie Végétales, UFR/SVT. 03 09 B.P. 848 Ouagadougou 09, Burkina Faso. 2 Senckenberg Research Institute, Department of Botany and molecular Evolution. Senckenberganlage 25, 60325. Frankfurt am Main, Germany 3 J.W. Goethe-University, Institute for Ecology, Evolution & Diversity. Siesmayerstr. 70, 60054. Frankfurt am Main, Germany * Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Biodiversity and Climate Research Institute (BiK-F), Senckenberganlage 25, 60325. Frankfurt am Main, Germany. Abstract: The Arly National Park of southeastern Burkina Faso is in the center of the WAP complex, the largest continuous unexplored until recently. The plant species composition is typical for sudanian savanna areas with a high share of grasses andsystem legumes of protected and similar areas toin otherWest Africa.protected Although areas wellof the known complex, for its the large neighbouring mammal populations, Pama reserve its andflora W has National largely Park.been Sahel reserve. The 490 species belong to 280 genera and 83 families. The most important life forms are phanerophytes and therophytes.It has more species in common with the classified forest of Kou in SW Burkina Faso than with the geographically closer Introduction vegetation than the surrounding areas, where agriculture For Burkina Faso, only very few comprehensive has encroached on savannas and forests and tall perennial e.g., grasses almost disappeared, so that its borders are even Guinko and Thiombiano 2005; Ouoba et al. -

Monographie Des Départements Du Zou Et Des Collines

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des départements du Zou et des Collines Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes du département de Zou Collines Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Tables des matières 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LE DEPARTEMENT ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS ZOU-COLLINES ...................................................................................... 6 1.1.1.1. Aperçu du département du Zou .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. GRAPHIQUE 1: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DU ZOU ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1.2. Aperçu du département des Collines .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2. GRAPHIQUE 2: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES .................................................................................... 10 1.1.2. -

Rapport Définitif De La Sélection Des 70 Formations Sanitaires (FS) Témoins Pour Les FS Du Projet FBR Du Bénin Par Joseph FLENON, Consultant

Rapport définitif de la sélection des 70 formations sanitaires (FS) témoins pour les FS du Projet FBR du Bénin par Joseph FLENON, Consultant. Dans la première partie du point n°1 de ce contrat en cours d’exécution, j’ai sélectionné de manière aléatoire simple 8 Zones Sanitaires (ZS) témoins (au lieu de 5 ou 6) pour les 8 ZS du projet FBR du Bénin et j’en ai fait un rapport Dans cette deuxième partie du point n°1, j’ai procédé à la sélection de 70 formations sanitaire (FS) dans 10 ZS témoins (au lieu de 8ZS témoins) car suivant les critères de sélection de ces FS, les 8ZS sélectionnées dans la première partie du point n°1, m’ont permis de sélectionner à leur tour 47 FS témoins au lieu de 70 FS témoins. La Sélection aléatoire simple d’une ZS contrôle dans chacun des 8 listes a donné les 8 ZS contrôles suivantes : 1.ZS Bohicon-Zakpota-Zogbodomey : ZS contrôle : ZS Djidja-Abomey-Agbangnizoun 2.ZS Covè-Ouinhi-Zangnanado : ZS contrôle : ZS Pobè-Ketou-Adja-Ouèrè 3.ZS Lokossa-Athiémé : ZS contrôle : ZS Aplahoué-Djakotomè-Dogbo 4.ZS Ouidah-Kpomassè-Tori-Bossito : ZS contrôle : ZS Allada-Toffo-Zê 5.ZS Porto-Novo-Aguégués-Sèmè-Podji : ZS contrôle : ZS Cotonou 6 6.ZS Adjohoun-Bonou-Dangbo : ZS contrôle : ZS Abomey-Calavi-Sô-Ava 7.ZS Banikoara : ZS contrôle : ZS Kandi-Gogounou-Ségbana 8.ZS Kouandé-Ouassa-Péhunco-Kérou : ZS contrôle : ZS Tanguiéta-Cobly-Matéri Les critères de sélections des FS témoins proposés dans les TDR peuvent être classés en critères exclusifs (être à moins de 15 km de la frontière d’une ZS du Projet FBR et avoir moins de 2 personnels qualifiés) et en critères non exclusifs (certaines FS témoins doivent avoir au moins 15 CPN par jour). -

W National Park in Niger—A Case for Urgent Assistance

W National Park for urgent John Grettenberger W National Park is shared by Niger, and infertile with a high iron content, particularly Upper Volta and Benin, and is recog- in the upland areas in the interior. Depressions nised as being one of the most important and stream valleys tend to have deeper, more fertile soils while extensive rock outcroppings are parks in West Africa by virtue of its size— found along the Niger and Mekrou Rivers. The 11,320 sq km—and its diversity of rainy season lasts from May to early October, with habitats and species*. Both its proximity an average rainfall of 700-800 mm, while the dry to the rapidly growing capital of Niamey, season is divided into a cold and a hot season. Niger, and the burgeoning trans-Saraha tourist traffic give it great tourist potential. Infrastructure and facilities The park and its wildlife, however, are W National Park of Niger is administered by the under constantly increasing pressure Direction of Forests and Wildlife, which is part of from poaching, illegal grazing, uncontrol- led bush fires, the possibility of phos- phate mining, and the lack of financial and material means to combat these pro- blems. The author is a US Peace Corps biologist who worked in Niger for four years, for part of the time attached to the IUCN/WWF aridlands project. He describes conditions and problems in the Niger sector of W National Park and discusses possible solutions. The Niger sector of W National Park is situated in the south-west of the country, between 11°55' N and 12°35'N and 2°5' E and 2°50' E.