Just Like in Colonial Times? Administrative Practice and Local Reflections on ‘Grassroots Neocolonialism’ in Autonomous and Postcolonial Dahomey, –

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace Sculptures of Abomey

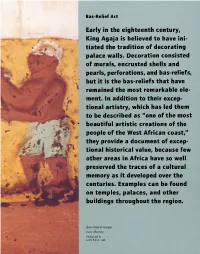

Bas-Relief Art Early in the eighteenth century, King Agaja is believed to have ini tiated the tradition of decorating palace walls. Decoration consisted of murals, encrusted shells and pearls, perfo rations, and bas-reliefs, , but it is the bas-reliefs that have remained the most remarkable ele ment. In addition to their excep tional artistry, which has led them to be described as "one of the most " beautiful artistic creations of the people of the West African coast, rr they provide a document of excep tional historical value, because few other areas in Africa have so well preserved the traces of a cultural · . memory as it developed over the centuries. Exa mples can be found on temples, palaces, and other buildings throughout the region. Bas-relief at temple near Abomey. Photograph by Leslie Railler, 1996. BAS-RELIEF ART 49 Commonly called noudide in Fon, from the root word meaning "to design" or "to portray," the bas-reliefs are three-dimensional, modeled- and painted earth pictograms. Early examples of the form, first in religious temples and then in the palaces, were more abstract than figurative. Gradually, figurative depictions became the prevalent style, illustrating the tales told by the kings' heralds and other Fon storytellers. Palace bas-reliefs were fashioned according to a long-standing tradition of The original earth architectural and sculptural renovation. used to make bas Ruling monarchs commissioned new palaces reliefs came from ter and artworks, as well as alterations of ear mite mounds such as lier ones, thereby glorifying the past while this one near Abomey. bringing its art and architecture up to date. -

S a Rd in Ia

M. Mandarino/Istituto Euromediterraneo, Tempio Pausania (Sardinia) Land07-1Book 1.indb 97 12-07-2007 16:30:59 Demarcation conflicts within and between communities in Benin: identity withdrawals and contested co-existence African urban development policy in the 1990s focused on raising municipal income from land. Population growth and a neoliberal environment weakened the control of clans and lineages over urban land ownership to the advantage of individuals, but without eradicating the importance of personal relationships in land transactions or of clans and lineages in the political structuring of urban space. The result, especially in rural peripheries, has been an increase in land aspirations and disputes and in their social costs, even in districts with the same territorial control and/or the same lines of nobility. Some authors view this simply as land “problems” and not as conflicts pitting locals against outsiders and degenerating into outright clashes. However, decentralization gives new dimensions to such problems and is the backdrop for clashes between differing perceptions of territorial control. This article looks at the ethnographic features of some of these clashes in the Dahoman historic region of lower Benin, where boundaries are disputed in a context of poorly managed urban development. Such disputes stem from land registries of the previous but surviving royal administration, against which the fragile institutions of the modern state seem to be poorly equipped. More than a simple problem of land tenure, these disputes express an internal rejection of the legitimacy of the state to engage in spatial structuring based on an ideal of co-existence; a contestation that is put forward with the de facto complicity of those acting on behalf of the state. -

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

Ficha País De Benin

OFICINA DE INFORMACIÓN DIPLOMÁTICA FICHA PAÍS Benín República de Benín La Oficina de Información Diplomática del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores, Unión Europea y de Cooperación pone a disposición de los profesionales de los me- dios de comunicación y del público en general la presente ficha país. La información contenida en esta ficha país es pública y se ha extraído de diversos medios no oficiales. La presente ficha país no defiende posición política alguna ni de este Ministerio ni del Gobierno de España respecto del país sobre el que versa. AGOSTO 2021 1. DATOS BÁSICOS Benín 1.1. Características generales NIGER Situación: La República de Benín está situada en África Occidental, entre el Sahel y el Golfo de Guinea, a 6-12º latitud N y 2º longitud Este. Limita con el Océano Atlántico en una franja costera de 121 km. Malanville BURKINA FASO Población: 12,1 millones (UNDP, 2020) Nombre oficial: República de Benín Superficie: 112.622 km² Ségbana Límites: Benin limita al norte con Burkina Faso y Níger, al sur con el Océano Atlántico al este con Nigeria y al oeste con Togo (1.989 km de fronteras). Banikoara Capital: Porto Novo es la capital oficial, sede de la Asamblea Nacional Kandi (268.000 habitantes); Cotonú es la sede del Gobierno y la ciudad más po- blada (750.000). Otras ciudades: Abomey – Calavi la ciudad más antigua (600.000); Parakou, Tanguieta Djougou, Bohicon y Kandi, las ciudades con más de 100.000 habitantes. Natitingou Idioma: Francés (lengua oficial); lenguas autóctonas: fon, bariba, yoruba, Bokoumbé adja, houeda y fulfulde. Religión y creencias: Cristianos católicos, evangélicos, presbiterianos (50%), Nikki Ndali musulmanes (30%), tradicional (animistas, vudú, 20%). -

Monographie Des Communes Des Départements De L'atlantique Et Du Li

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des communes des départements de l’Atlantique et du Littoral Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes Monographie départementale _ Mission de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin _ 2019 1 Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Monographie départementale _ Mission de spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin _ 2019 2 Tables des matières LISTE DES CARTES ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 SIGLES ET ABREVIATIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS DE L’ATLANTIQUE ET DU LITTORAL ................................................ 7 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LE DEPARTEMENT DE L’ATLANTIQUE ........................................................................................ 7 1.1.1.1. Présentation du Département de l’Atlantique ...................................................................................... -

Water Supply and Waterbornes Diseases in the Population of Za- Kpota Commune (Benin, West Africa)

International Journal of Engineering Science Invention (IJESI) ISSN (Online): 2319 – 6734, ISSN (Print): 2319 – 6726 www.ijesi.org ||Volume 7 Issue 6 Ver II || June 2018 || PP 33-39 Water Supply and Waterbornes Diseases in the Population of Za- Kpota Commune (Benin, West Africa) Léocadie Odoulami, Brice S. Dansou & Nadège Kpoha Laboratoire Pierre PAGNEY, Climat, Eau, Ecosystème et Développement LACEEDE)/DGAT/FLASH/ Université d’Abomey-Calavi (UAC). 03BP: 1122 Cotonou, République du Bénin (Afrique de l’Ouest) Corresponding Auther: Léocadie Odoulami Summary :The population of the common Za-kpota is subjected to several difficulties bound at the access to the drinking water. This survey aims to identify and to analyze the problems of provision in drinking water and the risks on the human health in the township of Za-kpota. The data on the sources of provision in drinking water in the locality, the hydraulic infrastructures and the state of health of the populations of 2000 to 2012 have been collected then completed by information gotten by selected 198 households while taking into account the provision difficulties in water of consumption in the households. The analysis of the results gotten watch that 43 % of the investigation households consume the water of well, 47 % the water of cistern, 6 % the water of boring, 3% the water of the Soneb and 1% the water of marsh. However, the physic-chemical and bacteriological analyses of 11 samples of water of well and boring revealed that the physic-chemical and bacteriological parameters are superior to the norms admitted by Benin. The consumption of these waters exposes the health of the populations to the water illnesses as the gastroenteritis, the diarrheas, the affections dermatologic,.. -

Monographie Des Départements Du Zou Et Des Collines

Spatialisation des cibles prioritaires des ODD au Bénin : Monographie des départements du Zou et des Collines Note synthèse sur l’actualisation du diagnostic et la priorisation des cibles des communes du département de Zou Collines Une initiative de : Direction Générale de la Coordination et du Suivi des Objectifs de Développement Durable (DGCS-ODD) Avec l’appui financier de : Programme d’appui à la Décentralisation et Projet d’Appui aux Stratégies de Développement au Développement Communal (PDDC / GIZ) (PASD / PNUD) Fonds des Nations unies pour l'enfance Fonds des Nations unies pour la population (UNICEF) (UNFPA) Et l’appui technique du Cabinet Cosinus Conseils Tables des matières 1.1. BREF APERÇU SUR LE DEPARTEMENT ....................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1. INFORMATIONS SUR LES DEPARTEMENTS ZOU-COLLINES ...................................................................................... 6 1.1.1.1. Aperçu du département du Zou .......................................................................................................... 6 3.1.1. GRAPHIQUE 1: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DU ZOU ............................................................................................... 7 1.1.1.2. Aperçu du département des Collines .................................................................................................. 8 3.1.2. GRAPHIQUE 2: CARTE DU DEPARTEMENT DES COLLINES .................................................................................... 10 1.1.2. -

Dynamics of the Inter Tropical Front and Rainy Season Onset in Benin

Current Journal of Applied Science and Technology 24(2): 1-15, 2017; Article no.CJAST.36832 Previously known as British Journal of Applied Science & Technology ISSN: 2231-0843, NLM ID: 101664541 Dynamics of the Inter Tropical Front and Rainy Season Onset in Benin Julien Djossou1,2*, Aristide B. Akpo1,2, Jules D. Afféwé3, Venance H. E. Donnou1,2, Catherine Liousse4, Jean-François Léon4, Fidèle G. Nonfodji1,2 and Cossi N. Awanou1,2 1Département de Physique (FAST), Formation Doctorale Sciences des Matériaux (FDSM), Université d’Abomey-Calavi, Bénin. 2Laboratoire de Physique du Rayonnement LPR, FAST-UAC, 01 BP 526 Cotonou, Bénin. 3Institut National de L’eau (INE), Université d’Abomey-Calavi, Bénin. 4Laboratoire d’Aérologie (LA), Toulouse, France. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Author ABA designed the study and wrote the protocol. Authors JD and JDA performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Authors CL, JFL and CNA managed the analyses of the study. Authors VHED and FGN managed the literature searches. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/CJAST/2017/36832 Editor(s): (1) Ndongo Din, Department of Botany, Faculty of Science, University of Douala, Cameroon, Africa. Reviewers: (1) Eresanya Emmanuel Olaoluwa, Federal University of Technology, Nigeria. (2) Brigadier Libanda, The University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom. (3) J. S. Ojo, Federal University of Technology, Nigeria. (4) Mojolaoluwa Daramola, Federal University of Technology Akure, Nigeria. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history/21496 Received 19th September 2017 Accepted 13th October 2017 Original Research Article Published 20th October 2017 ABSTRACT Rainfall onset in Benin is one of the major problems that the farmers face. -

Rapport Définitif De La Sélection Des 70 Formations Sanitaires (FS) Témoins Pour Les FS Du Projet FBR Du Bénin Par Joseph FLENON, Consultant

Rapport définitif de la sélection des 70 formations sanitaires (FS) témoins pour les FS du Projet FBR du Bénin par Joseph FLENON, Consultant. Dans la première partie du point n°1 de ce contrat en cours d’exécution, j’ai sélectionné de manière aléatoire simple 8 Zones Sanitaires (ZS) témoins (au lieu de 5 ou 6) pour les 8 ZS du projet FBR du Bénin et j’en ai fait un rapport Dans cette deuxième partie du point n°1, j’ai procédé à la sélection de 70 formations sanitaire (FS) dans 10 ZS témoins (au lieu de 8ZS témoins) car suivant les critères de sélection de ces FS, les 8ZS sélectionnées dans la première partie du point n°1, m’ont permis de sélectionner à leur tour 47 FS témoins au lieu de 70 FS témoins. La Sélection aléatoire simple d’une ZS contrôle dans chacun des 8 listes a donné les 8 ZS contrôles suivantes : 1.ZS Bohicon-Zakpota-Zogbodomey : ZS contrôle : ZS Djidja-Abomey-Agbangnizoun 2.ZS Covè-Ouinhi-Zangnanado : ZS contrôle : ZS Pobè-Ketou-Adja-Ouèrè 3.ZS Lokossa-Athiémé : ZS contrôle : ZS Aplahoué-Djakotomè-Dogbo 4.ZS Ouidah-Kpomassè-Tori-Bossito : ZS contrôle : ZS Allada-Toffo-Zê 5.ZS Porto-Novo-Aguégués-Sèmè-Podji : ZS contrôle : ZS Cotonou 6 6.ZS Adjohoun-Bonou-Dangbo : ZS contrôle : ZS Abomey-Calavi-Sô-Ava 7.ZS Banikoara : ZS contrôle : ZS Kandi-Gogounou-Ségbana 8.ZS Kouandé-Ouassa-Péhunco-Kérou : ZS contrôle : ZS Tanguiéta-Cobly-Matéri Les critères de sélections des FS témoins proposés dans les TDR peuvent être classés en critères exclusifs (être à moins de 15 km de la frontière d’une ZS du Projet FBR et avoir moins de 2 personnels qualifiés) et en critères non exclusifs (certaines FS témoins doivent avoir au moins 15 CPN par jour). -

Benin• Floods Rapport De Situation #13 13 Au 30 Décembre 2010

Benin• Floods Rapport de Situation #13 13 au 30 décembre 2010 Ce rapport a été publié par UNOCHA Bénin. Il couvre la période du 13 au 30 Décembre. I. Evénements clés Le PDNA Team a organisé un atelier de consolidation et de finalisation des rapports sectoriels Le Gouvernement de la République d’Israël a fait don d’un lot de médicaments aux sinistrés des inondations La révision des fiches de projets du EHAP a démarré dans tous les clusters L’Organisation Ouest Africaine de la Santé à fait don d’un chèque de 25 millions de Francs CFA pour venir en aide aux sinistrés des inondations au Bénin L’ONG béninoise ALCRER a fait don de 500.000 F CFA pour venir en aide aux sinistrés des inondations 4 nouveaux cas de choléra ont été détectés à Cotonou II. Contexte Les eaux se retirent de plus en plus et les populations sinistrés manifestent de moins en moins le besoin d’installation sur les sites de déplacés. Ceux qui retournent dans leurs maisons expriment des besoins de tentes individuelles à installer près de leurs habitations ; une demande appuyée par les autorités locales. La veille sanitaire post inondation se poursuit, mais elle est handicapée par la grève du personnel de santé et les lots de médicaments pré positionnés par le cluster Santé n’arrivent pas à atteindre les bénéficiaires. Des brigades sanitaires sont provisoirement mises en place pour faire face à cette situation. La révision des projets de l’EHAP est en cours dans les 8 clusters et le Post Disaster Needs Assessment Team est en train de finaliser les rapports sectoriels des missions d’évaluation sur le terrain dans le cadre de l’élaboration du plan de relèvement. -

Nigerian Journal of Rural Sociology Vol. 20, No. 1, 2020 INFORMATION

Nigerian Journal of Rural Sociology Vol. 20, No. 1, 2020 INFORMATION NEEDED WHILE USING ICTS AMONG MAIZE FARMERS IN DANGBO AND ADJOHOUN FARMERS IN SOUTHERN BENIN REPUBLIC 1Kpavode, A. Y. G., 2Akinbile, L. A. and 3Vissoh. P. V. Department of Agricultural Extension and Rural Development, University of Ibadan, Nigeria School of Economics, Socio-anthropology and Communication for Rural Development, University of Abomey Calavi, Benin Republic Correspondence contact details: [email protected] ABSTRACT This study assessed Information needed while using ICTs among maize farmers in Dangbo and Adjohoun in southern Benin Republic. Data were collected from a random sample of 150 maize farmers. The data collected were analysed using descriptive statistics and inferential statistics used were Chi-square, Pearson’s Product Moment Correlation and t-test at p=0.05. The results showed that farmers’ mean age was 43±1 years and were mostly male (88.0 %), married (88.0 %), Christians (67.3%) and 48.7% had no formal education. Prominent constraints to ICTs use were power supply ( =1.80) and high cost of maintenance of ICTs gadget ( =1.58). The most needed information by farmers using ICTs was on availability and cost of fertilisers insecticides and herbicides ( =1.20) and availability and cost of labour ( =1.16). Farmers’ constraints (t=2.832; p=0.005) significantly differed between Dangbo and Adjohoun communes. The information need of farmers in Dangbo and Adjohoun communes (t=0.753; p=0.453) do not significantly differ. The study concluded that the major barriers facing ICTs usage were power supply and high cost of maintenance of ICTs gadget; and there is the need for information on agricultural inputs. -

Malaria Vectors Resistance to Insecticides in Benin

Gnanguenon et al. Parasites & Vectors (2015) 8:223 DOI 10.1186/s13071-015-0833-2 RESEARCH Open Access Malaria vectors resistance to insecticides in Benin: current trends and mechanisms involved Virgile Gnanguenon1,2*, Fiacre R Agossa1,2, Kefilath Badirou1,2, Renaud Govoetchan1,2, Rodrigue Anagonou1,2, Fredéric Oke-Agbo1, Roseric Azondekon1, Ramziath AgbanrinYoussouf1,2, Roseline Attolou1,2, Filemon T Tokponnon4, Rock Aïkpon1,2, Razaki Ossè1,3 and Martin C Akogbeto1,2 Abstract Background: Insecticides are widely used to control malaria vectors and have significantly contributed to the reduction of malaria-caused mortality. In addition, the same classes of insecticides were widely introduced and used in agriculture in Benin since 1980s. These factors probably contributed to the selection of insecticide resistance in malaria vector populations reported in several localities in Benin. This insecticide resistance represents a threat to vector control tool and should be monitored. The present study reveals observed insecticide resistance trends in Benin to help for a better management of insecticide resistance. Methods: Mosquito larvae were collected in eight sites and reared in laboratory. Bioassays were conducted on the adult mosquitoes upon the four types of insecticide currently used in public health in Benin. Knock-down resistance, insensitive acetylcholinesterase-1 resistance, and metabolic resistance analysis were performed in the mosquito populations based on molecular and biochemical analysis. The data were mapped using Geographical Information Systems (GIS) with Arcgis software. Results: Mortalities observed with Deltamethrin (pyrethroid class) were less than 90% in 5 locations, between 90-97% in 2 locations, and over 98% in one location. Bendiocarb (carbamate class) showed mortalities ranged 90-97% in 2 locations and were over 98% in the others locations.