Benin Youth Assessment Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Palace Sculptures of Abomey

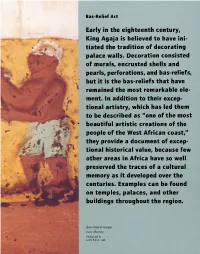

Bas-Relief Art Early in the eighteenth century, King Agaja is believed to have ini tiated the tradition of decorating palace walls. Decoration consisted of murals, encrusted shells and pearls, perfo rations, and bas-reliefs, , but it is the bas-reliefs that have remained the most remarkable ele ment. In addition to their excep tional artistry, which has led them to be described as "one of the most " beautiful artistic creations of the people of the West African coast, rr they provide a document of excep tional historical value, because few other areas in Africa have so well preserved the traces of a cultural · . memory as it developed over the centuries. Exa mples can be found on temples, palaces, and other buildings throughout the region. Bas-relief at temple near Abomey. Photograph by Leslie Railler, 1996. BAS-RELIEF ART 49 Commonly called noudide in Fon, from the root word meaning "to design" or "to portray," the bas-reliefs are three-dimensional, modeled- and painted earth pictograms. Early examples of the form, first in religious temples and then in the palaces, were more abstract than figurative. Gradually, figurative depictions became the prevalent style, illustrating the tales told by the kings' heralds and other Fon storytellers. Palace bas-reliefs were fashioned according to a long-standing tradition of The original earth architectural and sculptural renovation. used to make bas Ruling monarchs commissioned new palaces reliefs came from ter and artworks, as well as alterations of ear mite mounds such as lier ones, thereby glorifying the past while this one near Abomey. bringing its art and architecture up to date. -

B E N I N Benin

Birnin o Kebbi !( !( Kardi KANTCHARIKantchari !( !( Pékinga Niger Jega !( Diapaga FADA N'GOUMA o !( (! Fada Ngourma Gaya !( o TENKODOGO !( Guéné !( Madécali Tenkodogo !( Burkina Faso Tou l ou a (! Kende !( Founogo !( Alibori Gogue Kpara !( Bahindi !( TUGA Suroko o AIRSTRIP !( !( !( Yaobérégou Banikoara KANDI o o Koabagou !( PORGA !( Firou Boukoubrou !(Séozanbiani Batia !( !( Loaka !( Nansougou !( !( Simpassou !( Kankohoum-Dassari Tian Wassaka !( Kérou Hirou !( !( Nassoukou Diadia (! Tel e !( !( Tankonga Bin Kébérou !( Yauri Atakora !( Kpan Tanguiéta !( !( Daro-Tempobré Dammbouti !( !( !( Koyadi Guilmaro !( Gambaga Outianhou !( !( !( Borogou !( Tounkountouna Cabare Kountouri Datori !( !( Sécougourou Manta !( !( NATITINGOU o !( BEMBEREKE !( !( Kouandé o Sagbiabou Natitingou Kotoponga !(Makrou Gurai !( Bérasson !( !( Boukombé Niaro Naboulgou !( !( !( Nasso !( !( Kounounko Gbangbanrou !( Baré Borgou !( Nikki Wawa Nambiri Biro !( !( !( !( o !( !( Daroukparou KAINJI Copargo Péréré !( Chin NIAMTOUGOU(!o !( DJOUGOUo Djougou Benin !( Guerin-Kouka !( Babiré !( Afekaul Miassi !( !( !( !( Kounakouro Sheshe !( !( !( Partago Alafiarou Lama-Kara Sece Demon !( !( o Yendi (! Dabogou !( PARAKOU YENDI o !( Donga Aledjo-Koura !( Salamanga Yérémarou Bassari !( !( Jebba Tindou Kishi !( !( !( Sokodé Bassila !( Igbéré Ghana (! !( Tchaourou !( !(Olougbé Shaki Togo !( Nigeria !( !( Dadjo Kilibo Ilorin Ouessé Kalande !( !( !( Diagbalo Banté !( ILORIN (!o !( Kaboua Ajasse Akalanpa !( !( !( Ogbomosho Collines !( Offa !( SAVE Savé !( Koutago o !( Okio Ila Doumé !( -

Pdf Projdoc.Pdf

Tanguieta Toucountouna Benin Natitingou Perma Intervention areas: child protection, hunger and health Abomey Condji - Lokossa Cotonou Project “Nurse Me” This project stems from the need to support the children hosted in three of our accommodation centres in Benin, through the supply of powder milk. ‘Nurse me’ involves undernourished, motherless, neglected children or whose mothers are HIV positive, and who for these reasons can’t be breastfed during the first months of their lives. The project develops in the regions of Zou and Atacora, two areas in which inhabitants live mainly in rural villages. The health situation in these regions is alarming: childbirth mortality rate is extremely high and newborns are often underweight. Moreover, breastfeeding without blood ties is not contemplated in Benin’s culture. This factor, together with malnutrition, lack of hygiene, and the rampant plague of AIDS, causes several deceases. In addition to this, international aid has decreased, because of two issues: 1) the global economic crisis has led governments to reduce the aid to the countries of the South; 2) the World Food Programme has diminished the food aid in favour of Benin, in order to allocate more in support of countries at war. Insieme ai bambini del mondo Project objectives - Promote the right to life and health; - Prevent babies’ premature death caused by the impossibility of breastfeeding. Project beneficiaries - Undernourished, motherless, neglected children or whose mothers are HIV positive, who are hosted in our accommodation centres or monitored by the nutritional centre; - Families living in rural areas around our accommodation centres, which can benefit from a free health and nutritional service for their children. -

Les 6 Articles Du BRAB N° 48 Juin 2005

Bulletin de la Recherche Agronomique du Bénin Numéro 48 – Juin 2005 Identification et caractérisation des stations forestières pour un aménagement durable de la forêt classée de Toffo (Département du plateau ; sud–est du Bénin) O. S. N. L. DOSSA 10 , C. J. GANGLO 10 , V. ADJAKIDJÈ 11 , E. AGBOSSOU 10 et B. DE FOUCAULT 12 Résumé L’étude s’est déroulée dans la forêt classée de Toffo située entre 6°59’-7°01’ lat. Nord et 2°37-2°39’ long. Est. Elle a pour objectif d’asseoir les bases d’un aménagement et d’une gestion durable de la forêt. La végétation a été étudiée suivant l’approche synusiale ; les facteurs écologiques à travers la mesure des pentes, l’appréciation de la texture tactile, la description des profils pédologiques complétée par des analyses d’échantillons de sol au laboratoire. Les paramètres dendrométriques ont été mesurés dans des placettes circulaires de 14 m de rayon pour la forêt naturelle et de 10 m de rayon pour les plantations. Au total 16 synusies végétales ont été identifiées et intégrées en six phytocoenoses dont deux pionnières et quatre non pionnières. Des mesures d’aménagement ont été proposées à chacune des quatre stations forestières correspondant aux biotopes des phytocoenoses non pionnières. Mots clés : phytosociologie, stations forestières, aménagement, Toffo, Bénin. Identification and characterization of forest sites for sustainable management of Toffo forest reserve (Plateau Department ; south-east Benin) Abstract The study has been done in Toffo forest reserve (6°59-7°01’of North latitude and 2°37’-2°39’ of East longitude). Its purpose is to yield data on phytodiversity to help sustainable management of the forest. -

Inadequacy of Benin's and Senegal's Education Systems to Local and Global Job Markets: Pathways Forward; Inputs of the Indian and Chinese Education Systems

Clark University Clark Digital Commons International Development, Community and Master’s Papers Environment (IDCE) 5-2016 INADEQUACY OF BENIN'S AND SENEGAL'S EDUCATION SYSTEMS TO LOCAL AND GLOBAL JOB MARKETS: PATHWAYS FORWARD; INPUTS OF THE INDIAN AND CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEMS. Kpedetin Mignanwande [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers Part of the Higher Education Commons, International and Comparative Education Commons, Medicine and Health Sciences Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Mignanwande, Kpedetin, "INADEQUACY OF BENIN'S AND SENEGAL'S EDUCATION SYSTEMS TO LOCAL AND GLOBAL JOB MARKETS: PATHWAYS FORWARD; INPUTS OF THE INDIAN AND CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEMS." (2016). International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE). 24. https://commons.clarku.edu/idce_masters_papers/24 This Research Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Master’s Papers at Clark Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Development, Community and Environment (IDCE) by an authorized administrator of Clark Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. INADEQUACY OF BENIN'S AND SENEGAL'S EDUCATION SYSTEMS TO LOCAL AND GLOBAL JOB MARKETS: PATHWAYS FORWARD; INPUTS OF THE INDIAN AND CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEMS. Kpedetin S. Mignanwande May, 2016 A MASTER RESEARCH PAPER Submitted to the faculty of Clark University, Worcester, Massachusetts, in partial fulfill- ment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Arts in the department of International Development, Community, and Environment And accepted on the recommendation of Ellen E Foley, Ph.D. Chief Instructor, First Reader ABSTRACT INADEQUACY OF BENIN'S AND SENEGAL'S EDUCATION SYSTEMS TO LOCAL AND GLOBAL JOB MARKETS: PATHWAYS FORWARD; INPUTS OF THE INDIAN AND CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEMS. -

S a Rd in Ia

M. Mandarino/Istituto Euromediterraneo, Tempio Pausania (Sardinia) Land07-1Book 1.indb 97 12-07-2007 16:30:59 Demarcation conflicts within and between communities in Benin: identity withdrawals and contested co-existence African urban development policy in the 1990s focused on raising municipal income from land. Population growth and a neoliberal environment weakened the control of clans and lineages over urban land ownership to the advantage of individuals, but without eradicating the importance of personal relationships in land transactions or of clans and lineages in the political structuring of urban space. The result, especially in rural peripheries, has been an increase in land aspirations and disputes and in their social costs, even in districts with the same territorial control and/or the same lines of nobility. Some authors view this simply as land “problems” and not as conflicts pitting locals against outsiders and degenerating into outright clashes. However, decentralization gives new dimensions to such problems and is the backdrop for clashes between differing perceptions of territorial control. This article looks at the ethnographic features of some of these clashes in the Dahoman historic region of lower Benin, where boundaries are disputed in a context of poorly managed urban development. Such disputes stem from land registries of the previous but surviving royal administration, against which the fragile institutions of the modern state seem to be poorly equipped. More than a simple problem of land tenure, these disputes express an internal rejection of the legitimacy of the state to engage in spatial structuring based on an ideal of co-existence; a contestation that is put forward with the de facto complicity of those acting on behalf of the state. -

Projet De Vulgarisation De L'aquaculture Continentale En République Du Bénin Quatrième Session Ordinaire Du Comité De Suiv

Projet de Vulgarisation de l’Aquaculture Continentale en République du Bénin Bureau du Projet / Direction des Pêches Tel: 21 37 73 47 No 004 Le 22 Juillet 2011 Email: [email protected] Un an après son démarrage en juin 2011, le Projet de Vulgarisation de l’Aquaculture Continentale en République du Bénin (PROVAC), a connu un bilan positif meublé d’activités diverses mais essentiellement axées sur les formations de pisciculteurs ordinaires par l’approche « fermier à fermier »démarré au début du mois de juin 2010, poursuit ses activités et vient d’amor‐ cer le neuvième mois de sa mise en œuvre. Quatrième session ordinaire du Comité de Suivi Le Mercredi 18 Mai 2011 s’est tenue, dans la salle de formation de la Direction des Pêches à Cotonou, la quatrième session ordinaire du Comité de Suivi du Projet de Vulgarisation de l’Aqua‐ culture Continentale en République du Bénin (PROVAC). Cette rencontre a connu la participation des membres du Comité de Suivi désignés par les quatre Centres Régionaux pour la Promotion Agricole (CeRPA) impliqués dans le Projet sur le terrain et a été rehaussée par la présence de la Représentante Résidente de la JICA au Bénin. A cette session, les CeRPA Ouémé/Plateau, Atlantique/Littoral, Zou/Collines et Mono/Couffo ont fait le point des activités du Projet sur le terrain, d’une part, et le Plan de Travail Annuel (PTA) 4e session ordinaire approuvé à Tokyo par la JICA au titre de l’année japonaise 2011 a été exposé, d’autre part, par le du Comité du Suivi Chef d’équipe des experts. -

Female Genital Cutting

DHS Comparative Reports 7 Female Genital Cutting in the Demographic and Health Surveys: A Critical and Comparative Analysis MEASURE DHS+ assists countries worldwide in the collection and use of data to monitor and evaluate population, health, and nutrition programs. Funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), MEASURE DHS+ is implemented by ORC Macro in Calverton, Maryland. The main objectives of the MEASURE DHS+ project are: 1) to provide decisionmakers in survey countries with information useful for informed policy choices, 2) to expand the international population and health database, 3) to advance survey methodology, and 4) to develop in participating countries the skills and resources necessary to conduct high-quality demographic and health surveys. Information about the MEASURE DHS+ project or the status of MEASURE DHS+ surveys is available on the Internet at http://www.measuredhs.com or by contacting: ORC Macro 11785 Beltsville Drive, Suite 300 Calverton, MD 20705 USA Telephone: 301-572-0200 Fax: 301-572-0999 E-mail: [email protected] DHS Comparative Reports No. 7 Female Genital Cutting in the Demographic and Health Surveys: A Critical and Comparative Analysis P. Stanley Yoder Noureddine Abderrahim Arlinda Zhuzhuni ORC Macro Calverton, Maryland, USA September 2004 This publication was made possible through support provided by the U.S. Agency for International Development under the terms of Contract No. HRN-C-00-97-00019- 00. The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Agency for International Development. Editor: Sidney Moore Series design: Katherine Senzee Document production: Justine Faulkenburg Recommended citation: Yoder, P. -

Online Appendix to “Can Informed Public Deliberation Overcome Clientelism? Experimental Evidence from Benin”

Online Appendix to “Can Informed Public Deliberation Overcome Clientelism? Experimental Evidence from Benin” by Thomas Fujiwara and Leonard Wantchekon 1. List of Sample Villages Table A1 provides a list of sample villages, with their experimental and dominant can- didates. 2. Results by Commune/Stratum Table A2.1-A2.3 presents the results by individual commune/stratum. 3. Survey Questions and the Clientelism Index Table A3.1 provides the estimates for each individual component of the clientelism index, while Table A3.2 details the questions used in the index. 4. Treatment Effects on Candidate Vote Shares Table A4 provides the treatment effect on each individual candidate vote share. 5. Estimates Excluding Communes where Yayi is the EC Table A5 reports results from estimations that drop the six communes where Yayi is the EC. Panel A provides estimates analogous from those of Table 2, while Panels B and C report estimates that are similar to those of Table 3. The point estimates are remarkably similar to the original ones, even though half the sample has been dropped (which explains why some have a slight reduction in significance). 1 6. Estimates Including the Commune of Toffo Due to missing survey data, all the estimates presented in the main paper exclude the commune of Toffo, the only one where Amoussou is the EC. However, electoral data for this commune is available. This allows us to re-estimate the electoral data-based treatment effects including the commune. Table A6.1 re-estimates the results presented on Panel B of Table 2. The qualitative results remain the same. -

The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte D'ivoire, and Togo

Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Public Disclosure Authorized Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon Public Disclosure Authorized 00000_CVR_English.indd 1 12/6/17 2:29 PM November 2017 The Geography of Welfare in Benin, Burkina Faso, Côte d’Ivoire, and Togo Nga Thi Viet Nguyen and Felipe F. Dizon 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 1 11/29/17 3:34 PM Photo Credits Cover page (top): © Georges Tadonki Cover page (center): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Cover page (bottom): © Curt Carnemark/World Bank Page 1: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 7: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 15: © Adrian Turner/Flickr Page 32: © Dominic Chavez/World Bank Page 48: © Arne Hoel/World Bank Page 56: © Ami Vitale/World Bank 00000_Geography_Welfare-English.indd 2 12/6/17 3:27 PM Acknowledgments This study was prepared by Nga Thi Viet Nguyen The team greatly benefited from the valuable and Felipe F. Dizon. Additional contributions were support and feedback of Félicien Accrombessy, made by Brian Blankespoor, Michael Norton, and Prosper R. Backiny-Yetna, Roy Katayama, Rose Irvin Rojas. Marina Tolchinsky provided valuable Mungai, and Kané Youssouf. The team also thanks research assistance. Administrative support by Erick Herman Abiassi, Kathleen Beegle, Benjamin Siele Shifferaw Ketema is gratefully acknowledged. Billard, Luc Christiaensen, Quy-Toan Do, Kristen Himelein, Johannes Hoogeveen, Aparajita Goyal, Overall guidance for this report was received from Jacques Morisset, Elisée Ouedraogo, and Ashesh Andrew L. Dabalen. Prasann for their discussion and comments. Joanne Gaskell, Ayah Mahgoub, and Aly Sanoh pro- vided detailed and careful peer review comments. -

The Family Economy and Agricultural Innovation in West Africa: Towards New Partnerships

THE FAMILY ECONOMY AND AGRICULTURAL INNOVATION IN WEST AFRICA: TOWARDS NEW PARTNERSHIPS Overview An Initiative of the Sahel and West Africa Club (SWAC) Secretariat SAH/D(2005)550 March 2005 Le Seine Saint-Germain 4, Boulevard des Iles 92130 ISSY-LES-MOULINEAUX Tel. : +33 (0) 1 45 24 89 87 Fax : +33 (0) 1 45 24 90 31 http://www.oecd.org/sah Adresse postale : 2 rue André-Pascal 75775 Paris Cedex 16 Transformations de l’agriculture ouest-africaine Transformation of West African Agriculture 0 2 THE FAMILY ECONOMY AND AGRICULTURAL INNOVATION IN WEST AFRICA: TOWARDS NEW PARTNERSHIPS Overview SAH/D(2005)550 March, 2005 The principal authors of this report are: Dr. Jean Sibiri Zoundi, Regional Coordinator of the SWAC Secretariat Initiative on access to agricultural innovation, INERA Burkina Faso ([email protected]). Mr. Léonidas Hitimana, Agricultural Economist, Agricultural Transformation and Sustainable Development Unit, SWAC Secretariat ([email protected]) Mr. Karim Hussein, Head of the Agricultural Transformation and Sustainable Development Unit, SWAC Secretariat, and overall Coordinator of the Initiative ([email protected]) 3 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS Headquarters AAGDS Accelerated Agricultural Growth Development Strategy Ghana ADB African Development Bank Tunisia ADF African Development Fund Tunisia ADOP Appui direct aux opérateurs privés (Direct Support for Private Sector Burkina Faso Operators) ADRK Association pour le développement de la région de Kaya (Association for the Burkina Faso (ADKR) Development of the -

ICT in Education in Benin

SURVEY OF ICT AND EDUCATION IN AFRICA: Benin Country Report ICT in Education in Benin by Osei Tutu Agyeman June 2007 Source: World Fact Book1 Disclaimer Statement Please note: This short Country Report, a result of a larger infoDev-supported Survey of ICT in Education in Africa, provides a general overview of current activities and issues related to ICT use in education in the country. The data presented here should be regarded as illustrative rather than exhaustive. ICT use in education is at a particularly dynamic stage in Africa; new developments and announcements happening on a daily basis somewhere on the continent. Therefore, these reports should be seen as “snapshots” that were current at the time they were taken; it is expected that certain facts and figures presented may become dated very quickly. The findings, interpretations and conclusions expressed herein are entirely those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the view of infoDev, the Donors of infoDev, the World Bank and its affiliated organizations, the Board of Executive Directors of the World Bank or the governments they represent. The World Bank cannot guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply on the part of the World Bank any judgment of the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. It is expected that individual Country Reports from the Survey of ICT and Education in Africa will be updated in an iterative process over time based on additional research and feedback received through the infoDev web site.