Aliya Chalutzit from America, 1939-48

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introduction Really, 'Human Dust'?

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Peck, The Lost Heritage of the Holocaust Survivors, Gesher, 106 (1982) p.107. 2. For 'Herut's' place in this matter, see H. T. Yablonka, 'The Commander of the Yizkor Order, Herut, Shoa and Survivors', in I. Troen and N. Lucas (eds.) Israel the First Decade, New York: SUNY Press, 1995. 3. Heller, On Struggling for Nationhood, p. 66. 4. Z. Mankowitz, Zionism and the Holocaust Survivors; Y. Gutman and A. Drechsler (eds.) She'erit Haplita, 1944-1948. Proceedings of the Sixth Yad Vas hem International Historical Conference, Jerusalem 1991, pp. 189-90. 5. Proudfoot, 'European Refugees', pp. 238-9, 339-41; Grossman, The Exiles, pp. 10-11. 6. Gutman, Jews in Poland, pp. 65-103. 7. Dinnerstein, America and the Survivors, pp. 39-71. 8. Slutsky, Annals of the Haganah, B, p. 1114. 9. Heller The Struggle for the Jewish State, pp. 82-5. 10. Bauer, Survivors; Tsemerion, Holocaust Survivors Press. 11. Mankowitz, op. cit., p. 190. REALLY, 'HUMAN DUST'? 1. Many of the sources posed problems concerning numerical data on immi gration, especially for the months leading up to the end of the British Mandate, January-April 1948, and the first few months of the state, May August 1948. The researchers point out that 7,574 immigrant data cards are missing from the records and believe this to be due to the 'circumstances of the times'. Records are complete from September 1948 onward, and an important population census was held in November 1948. A parallel record ing system conducted by the Jewish Agency, which continued to operate after that of the Mandatory Government, provided us with statistical data for immigration during 1948-9 and made it possible to analyse the part taken by the Holocaust survivors. -

Project Aim and Objectives

1 MICROZONING OF THE EARTHQUAKE HAZARD IN ISRAEL PROJECT 9 SITE SPECIFIC EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS ASSESSMENT USING AMBIENT NOISE MEASUREMENTS IN HADERA, PARDES HANNA, BINYAMINA AND NEIGHBORING SETTLEMENTS November, 2009 Job No 526/473/09 Principal Investigator: Dr. Yuli Zaslavsky Collaborators G. Ataev, M. Gorstein, M. Kalmanovich, D. Giller, I. Dan, N. Perelman, T. Aksinenko, V. Giller, and A. Shvartsburg Submitted to: Earth Sciences Research Administration National Ministry of Infrastructures Contract Number: 28-17-054 2 CONTENT LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................... 4 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 7 Empirical approaches implemented in the analysis of site effect ................................................ 8 GEOLOGICAL OUTLINE ............................................................................................................ 10 Quaternary sediments ................................................................................................................. 12 Tertiary rocks ............................................................................................................................ -

Parries Hanna

637 Parries Hanna Horvitz & Horvitz Book & Nwsppr Agcy Leitner Benjamin Hadar Ins Co Ltd Mossenson Zipora & Amos Ricss Shalom (near Egged Bus Stn) . .70 97 Derech Karkur 74 83 56 Talmei Elazar 73 82 5 Shikun Rassco 72 26 Rifer Hana & Yehoshua Hospital Neve Shalvah Ltd 70 58 Lcnshitzki Shelomo Butchershop.. .72 67 Motro Samuel Car Dealer Rehov Harishonim Karkur 74 33 Levi Hermann & Lucie Rehov Harishonim 74 69 Robeosohn Dr Friedrich Rehov Ha'atzmaut Karkur 73 51 Mozes Walter Farmer Shekhunat Meged 70 30 Levit Abraham Devora & Thiya Rehov Habotnim 71 93 Robinson Abraham Derech Hanadiv71 18 Invalids Home Tel Alon Karkur 73 94 Mueller Sbelomit Rehov Hadekalim .70 34 Roichman Bros (Shomron) Ltd (near Meged) 72 83 Mahzevet Iron 74 43 Inwald F A Rehov Hanassi 73 95 Levy Otto Farmer Rehov Habotnim .72 09 Rosenau Chana Rehov Habotnim .74 79 Inwentash Josef Metal Wks Levy Tclma & Gad N Rosenbaum Dr Julius Phys Rehov Harishonim 74 36 Shechunat Rassco 21 74 24 Nachimovic Hava & Lipa Gan Hashomron 71 75 Iron Co-op Bakery Ltd Karkur .. .70 72 Lewi David Pension Kefar Pines . .73 40 Rehov Hapalmah 73 61 Rotenberg Abraham Agric Machs Lewin Ernst Jehuda Ishaky Dov Fuel & Lubr Stn Nadaf Rashid Mussa Farmer Moshav Talmei Elazar 71 12 Shekhunat Meged 72 56 Shikun Ammami 23 Karkur 73 29 Baqa El Gharbiya 71 53 Rubinstein Ami-Netzah Bet Olim D' .72 58 Liptscher Katricl & Menahem Crpntry Itin Shoshana & Ben-Zion Nattel Jacob Agcy of Carmei Oriental Rubinstein Hayim Derech Hanadiv . .71 50 Rehov Gilad 71 89 Rehov Hadekalim 70 94 Wines & Nesher Beer Lishkat Hammas Karkur 72 94 Itzkovits Aharon Car Elecn Rehov Haharuvim 72 69 S Pardes Hanna Rehov Hadkalim .70 73 Main Rd 74'40 Neumann Miriam & Kurt Local Council Baqa El Gharbiya 72 23 Sachs Dr Yehuda Gan Hashomron. -

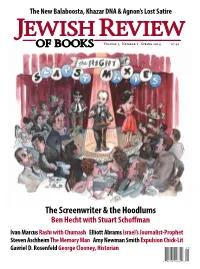

JEWISH REVIEW of BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95

The New Balaboosta, Khazar DNA & Agnon’s Lost Satire JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95 The Screenwriter & the Hoodlums Ben Hecht with Stuart Schoffman Ivan Marcus Rashi with Chumash Elliott Abrams Israel’s Journalist-Prophet Steven Aschheim The Memory Man Amy Newman Smith Expulsion Chick-Lit Gavriel D. Rosenfeld George Clooney, Historian NEW AT THE Editor CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY Abraham Socher Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Associate Editor Amy Newman Smith Administrative Assistant Rebecca Weiss Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Publisher Eric Cohen Associate Publisher & Director of Marketing Lori Dorr NEW SPACE The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, The David Berg Rare Book Room is a state-of- Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication the-art exhibition space preserving and dis- of ideas and criticism published in Spring, Summer, playing the written word, illuminating Jewish Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 165 East 56th Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10022. history over time and place. For all subscriptions, please visit www.jewishreviewofbooks.com or send $29.95 UPCOMING EXHIBITION ($39.95 outside of the U.S.) to Jewish Review of Books, Opening Sunday, March 16: By Dawn’s Early PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834. Please send notifi- cations of address changes to the same address or to Light: From Subjects to Citizens (presented by the [email protected]. -

Hagefen August 11, 2017

Hagefen www.gfn.co.il August 11, 2017 MENASHE SECTION Menashe Regional Council chair Ilan Sadeh signs the plan for the new industrial zone: Menashe Regional Council The Industrial Zone in Menashe: Planning completed for the Iron Industrial Zone The Menashe Regional Council has completed planning for the Iron Industrial Zone, with all approvals in hand Architect Leah Perry, engineer for the Menashe-Alona Regional Planning and Building Committee, noted that the land area chosen – part of the Menashe regional jurisdiction between the Menashe Regional Center and the Barkai intersection – is close to the country’s main transportation network, in proximity to the Iron interchange on Trans-Israel Highway 6 as well as Highway 2, Route 65 and Israel Railways. The location is also consonant with the master plan for Wadi Ara development. The industrial zone has a total area of 1085 dunams (c. 268 acres), with 628,000 square meters for industrial and commercial buildings and another c. 15,000 square meters of public buildings. by Yaniv Golan This week Menashe Regional Council chairman Ilan Sadeh and architect Leah Perry, the council engineer for the Menashe-Alona Regional Planning and Building Committee, signed off on the plans, which were forwarded for registration with the Haifa District Planning and Building Committee, prior to final approval of the plans. The Iron Industrial Zone will be shared by six Jewish and Arab local councils in the northern Sharon area of Wadi Ara. The new industrial zone is an initiative of Menashe Regional Council chairman Ilan Sadeh. Behind this project is a unique Jewish-Arab partnership involving Jewish councils – the Menashe regional council and the Harish local council – alongside a series of Arab councils in Wadi Ara – the Umm al Fahm municipality, the Kfar Qara local council, the Basma local council (comprising Barta’a, Ein a-Sahle and Muawiya) and the Arara local council. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Imagining the Border

A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan A WAshington institute str Ategic r eport Imagining the Border Options for Resolving the Israeli-Palestinian Territorial Issue z David Makovsky with Sheli Chabon and Jennifer Logan All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2011 The Washington Institute for Near East Policy Published in 2011 in the United States of America by the Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050, Washington, DC 20036. Design by Daniel Kohan, Sensical Design and Communication Front cover: President Barack Obama watches as Israeli prime minister Binyamin Netanyahu and Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas shake hands in New York, September 2009. (AP Photo/Charles Dharapak) Map CREDITS Israeli settlements in the Triangle Area and the West Bank: Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007, 2008, and 2009 data Palestinian communities in the West Bank: Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, 2007 data Jerusalem neighborhoods: Jerusalem Institute for Israel Studies, 2008 data Various map elements (Green Line, No Man’s Land, Old City, Jerusalem municipal bounds, fences, roads): Dan Rothem, S. Daniel Abraham Center for Middle East Peace Cartography: International Mapping Associates, Ellicott City, MD Contents About the Authors / v Acknowledgments / vii Settlements and Swaps: Envisioning an Israeli-Palestinian Border / 1 Three Land Swap Scenarios / 7 Maps 1. -

Front Matter May 8

LINGUISTIC AND SPATIAL PRACTICE IN A DIVIDED LANDSCAPE by Abigail Sone A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of PhD Graduate Department of Anthropology University of Toronto © Copyright by Abigail Sone 2009 LINGUISTIC AND SPATIAL PRACTICE IN A DIVIDED LANDSCAPE Abigail Sone Department of Anthropology University of Toronto PhD 2009 Abstract of Thesis This dissertation demonstrates how changes in spatial boundaries map on to changes in the boundaries of national belonging through an ethnography of linguistic and spatial practice in a divided landscape. In Israel, as in many places around the globe, new forms of segregation have emerged in recent years, as violence and the fear of violence become increasingly bound up with the production of social difference and exclusion. In Wadi Ara, a valley in the north of the country where my fieldwork was based, segregation between Jewish and Palestinian citizens has dramatically increased since the fall of 2000, as the place of Palestinians in a Jewish state is being reconfigured. In this dissertation I focus on the changing movements and interactions of Jewish Israelis in Wadi Ara as they articulate with changes in the ways difference, belonging, and citizenship are organized on a national scale. I examine how increased hostility, fear, and distrust have become spatialized; how narratives of the past shape contemporary geographies; how competing ways of interpreting and navigating the landscape are mediated; and how particular forms of encounter are framed. My central argument is that through daily linguistic and spatial practice people in Wadi Ara do more than just make sense of shifting boundaries; they bring these boundaries into being and, in the process, they enact both self‐definition and exclusion, reflecting and circumscribing ii the changing place of Palestinians in Israel. -

The Old Courtyard at Kibbutz Ein Shemer in Israel, Fun, Attractions, Must See

The old courtyard at Kibbutz Ein Shemer in Israel, fun, attractions, must see... file:///C:/Users/uniqo3/Desktop/WORK/UNiQO/customers/courtyard/N... Tractors in Kibbutz Ein Shemer, Israel Kibbutz Ein Shemer hosts one of the most amazing early and completely restored collection of tractors at the "Michael Hanger". What makes this collection so unique is the amount of detailed work invested by our team to restore the tractors back to their original condition sometimes as early as 1875! Come visit history in the making at Kibbutz Ein Shemer. Please confirm the business hours for both museum and tractor hanger by phone +972-4-637-4237 or by email [email protected]. Motorized plow "Stock" Stock type tractor restoration from (Germany, 1910) 1917 Imported to Israel in 1912. The motorized plow, Developed in 1910 by a German which was called “The Mechanical Mule,” was one engineer named Robert Stock in his stage in the transition from horse-drawn plowing tractor factory. This tractor was to tractor plowing. equipped with gasoline engine with two cylinders gearbox. A standard horse-drawn tractor is attached at the In 1915, two tractors were brought to rear. Instead of the horses, the plow is towed by Israel by German Templars, who puller wheels powered by a gasoline engine. From established a farm near Beit Shean. We the premises of Nira and Yehuda Lerner, Gedera. received the tractor in very poor shape, motor gear was destroyed and the body Stationary threshing machine corn on the cob of the tractor was rusted. USA, 1920) After nearly two years of detailed Corn-threshing machines were imported to Israel restoration this tractor is now displayed at the beginning of the 20th century. -

UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 20-F (Mark One) REGISTRATION STATEMENT PURSUANT TO SECTION 12(b) OR (g) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 OR ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2012 OR TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the transition period from ______ to ______ OR SHELL COMPANY REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 or 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of event requiring this shell company report _________________________ Commission File Number 001-35464 CAESARSTONE SDOT-YAM LTD. (Exact Name of Registrant as specified in its charter) ISRAEL (Jurisdiction of incorporation or organization) Kibbutz Sdot-Yam MP Menashe, 3780400 Israel (Address of principal executive offices) Yosef Shiran Chief Executive Officer Caesarstone Sdot-Yam Ltd. MP Menashe, 3780400 Israel Telephone: +972 (4) 636-4555 Fascimile: +972 (4) 636-4400 (Name, telephone, email and/or facsimile number and address of company contact person) Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Securities Act of 1933 (“Securities Act”): Title of each class Name of each exchange on which registered Ordinary Shares, par value NIS 0.04 per share Nasdaq Global Select Market Securities registered or to be registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Securities for which there is a reporting obligation pursuant to Section 15(d) of the Act: None Indicate -

West Bank Area Is 6,195 Km2 (Includes Shomron Northwest Portion of Dead Sea, One-Half of No Man's Land, and All of 3 East Jerusalem Except Mount Scopus)

Israeli to Palestinian See “Map 5a: Afula Area* Km2 % of Baseline† Triangle Detail” A North 18.7 .30% B Northwest 2.2 .04% C Southwest 25.1 .40% Umm Mt. Gilboa D South 13.3 .21% Al-Fahm E Gaza 87.6 1.41% Kafr Qara H Beit Shean F Chalutzah not included not included G Southwest 2 not included not included Umm Jenin H Triangle 146.2 2.36% Al-Qutuf TOTAL‡ 293.1 4.73 % A Palestinian to Israeli H % of Settler % of Total Bloc Km2 Baseline† Population** Settlers 1 North of Ariel 31.0 .50% 11,621 3.89% 2 Ariel 29.6 .48% 19,737 6.60% 3 Western Edge/ 105.3 1.70% 79,687 26.65% B Modiin Illit†† 4 Expanded Ofra/Bet El 26.1 .42% 20,023 6.70% Tulkarem 5 North of Jerusalem 10.9 .18% 15,866 5.31% Qalansawe 6 East Jerusalem 29.1 .47% not included not included Jewish neighborhoods Tayibe 7 Maale Adumim 10.8 .17% 34,600 11.57% H Kfar Adumim 5.8 .09% 2,800 .94% 8 Betar Illit/Gush Etzion 42.8 .69% 54,012 18.06% Tire Kedumim Nablus 9 Southern Edge 1.7 .03% 900 .30% TOTAL‡ 293.1 4.73% 239,246‡‡ 80.01%*** Qalqiliya 1 * Areas considered unpopulated. Alfe Karne Menashe Immanuel † Baseline figure for total Gaza/West Bank area is 6,195 km2 (includes Shomron northwest portion of Dead Sea, one-half of No Man's Land, and all of 3 east Jerusalem except Mount Scopus). ‡ Totals derived from rounding decimal numbers. -

The PUA English Report 2011-2012

Editor: Nurit Felter-Eitan, Authority Secretary & Spokeswoman All information provided in this report is provided for information purposes only and does not constitute a legal act. The hebrew translation is the current and accurate information. Information in this report is subject to change without prior notice. Greetings, I am delighted to hereby present the Israel Public Utility Authority’s (Electricity) biennial activity report for the years 2012-2011. This report summarizes the Authority’s Assembly’s extensive and meticulous work, assisted by the Authority’s team of professional employees, over the past two years, signifying a turning point in the Israeli electricity and energy markets. Alongside a severe energy crisis that befell the electricity market in the past two years due to the discontinuation of natural gas supply from Egypt and the creation of a gas supply monopoly, these years have seen a historic change in the electricity market, commencing with the admission of private electricity entrepreneurship and clean electricity production in significant capacities (the Authority’s projection for private electricity production is 25% by 2016, and approximately 10% for electricity production using renewable energy by 2020). As a result of the natural gas crisis, which began in 2011 due to recurring explosions in the gas lines leading from Egypt to Israel, the Electricity Authority was faced with a reality that would have forced it to instantly and radically increase in the electricity tariffs for the Israeli consumers in 2012. These circumstances led the Authority to combine forces with government bodies, including the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Energy and Water Resources and the Ministry of Environmental Protection, and lead a comprehensive move which significantly restrained the tariff increase, and furthermore, relieved the electricity consumers’ burden in a manner that enabled spreading the tariff increase over three years.