The Tanks of Tammuz and the Seventh

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aliya Chalutzit from America, 1939-48

1 Aliya of American Pioneers By Yehuda Sela (Silverman) From Hebrew: Arye Malkin A) Aliya1 Attempts During WW II The members of the Ha‟Shomer Ha‟Tzair2 Zionist Youth Movement searched a long time for some means to get to the shores of the Land of Israel (Palestine). They all thought that making Aliya was preferable to joining the Canadian or the American Army, which would possibly have them fighting in some distant war, unrelated to Israel. Some of these efforts seem, in retrospect, unimaginable, or at least naïve. There were a number of discussions on this subject in the Secretariat of Kibbutz Aliya Gimel (hereafter: KAG) and the question raised was whether individual private attempts to make Aliya should be allowed. The problems were quite complicated, and rather than deciding against the effort to make Aliya, it was decided to allow these efforts in special cases. Later on the Secretariat decided against these private individual efforts. The members attempted several ways to pursue this goal, but none were successful. Some applied for a truck driver position with a company that operated in Persia, building roads to connect the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea. Naturally, holding a driving license that did not qualify one for heavy vehicles did not help. Another way was to volunteer to be an ambulance driver in the Middle East, an operation that was being run by the Quakers; this was a pacifist organization that had carried out this sort of work during the First World War. An organization called „The American Field Service‟ recruited its members from the higher levels of society. -

Introduction Really, 'Human Dust'?

Notes INTRODUCTION 1. Peck, The Lost Heritage of the Holocaust Survivors, Gesher, 106 (1982) p.107. 2. For 'Herut's' place in this matter, see H. T. Yablonka, 'The Commander of the Yizkor Order, Herut, Shoa and Survivors', in I. Troen and N. Lucas (eds.) Israel the First Decade, New York: SUNY Press, 1995. 3. Heller, On Struggling for Nationhood, p. 66. 4. Z. Mankowitz, Zionism and the Holocaust Survivors; Y. Gutman and A. Drechsler (eds.) She'erit Haplita, 1944-1948. Proceedings of the Sixth Yad Vas hem International Historical Conference, Jerusalem 1991, pp. 189-90. 5. Proudfoot, 'European Refugees', pp. 238-9, 339-41; Grossman, The Exiles, pp. 10-11. 6. Gutman, Jews in Poland, pp. 65-103. 7. Dinnerstein, America and the Survivors, pp. 39-71. 8. Slutsky, Annals of the Haganah, B, p. 1114. 9. Heller The Struggle for the Jewish State, pp. 82-5. 10. Bauer, Survivors; Tsemerion, Holocaust Survivors Press. 11. Mankowitz, op. cit., p. 190. REALLY, 'HUMAN DUST'? 1. Many of the sources posed problems concerning numerical data on immi gration, especially for the months leading up to the end of the British Mandate, January-April 1948, and the first few months of the state, May August 1948. The researchers point out that 7,574 immigrant data cards are missing from the records and believe this to be due to the 'circumstances of the times'. Records are complete from September 1948 onward, and an important population census was held in November 1948. A parallel record ing system conducted by the Jewish Agency, which continued to operate after that of the Mandatory Government, provided us with statistical data for immigration during 1948-9 and made it possible to analyse the part taken by the Holocaust survivors. -

Project Aim and Objectives

1 MICROZONING OF THE EARTHQUAKE HAZARD IN ISRAEL PROJECT 9 SITE SPECIFIC EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS ASSESSMENT USING AMBIENT NOISE MEASUREMENTS IN HADERA, PARDES HANNA, BINYAMINA AND NEIGHBORING SETTLEMENTS November, 2009 Job No 526/473/09 Principal Investigator: Dr. Yuli Zaslavsky Collaborators G. Ataev, M. Gorstein, M. Kalmanovich, D. Giller, I. Dan, N. Perelman, T. Aksinenko, V. Giller, and A. Shvartsburg Submitted to: Earth Sciences Research Administration National Ministry of Infrastructures Contract Number: 28-17-054 2 CONTENT LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................... 4 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 7 Empirical approaches implemented in the analysis of site effect ................................................ 8 GEOLOGICAL OUTLINE ............................................................................................................ 10 Quaternary sediments ................................................................................................................. 12 Tertiary rocks ............................................................................................................................ -

The Land of Israel Symbolizes a Union Between the Most Modern Civilization and a Most Antique Culture. It Is the Place Where

The Land of Israel symbolizes a union between the most modern civilization and a most antique culture. It is the place where intellect and vision, matter and spirit meet. Erich Mendelsohn The Weizmann Institute of Science is one of Research by Institute scientists has led to the develop- the world’s leading multidisciplinary basic research ment and production of Israel’s first ethical (original) drug; institutions in the natural and exact sciences. The the solving of three-dimensional structures of a number of Institute’s five faculties – Mathematics and Computer biological molecules, including one that plays a key role in Science, Physics, Chemistry, Biochemistry and Biology Alzheimer’s disease; inventions in the field of optics that – are home to 2,600 scientists, graduate students, have become the basis of virtual head displays for pilots researchers and administrative staff. and surgeons; the discovery and identification of genes that are involved in various diseases; advanced techniques The Daniel Sieff Research Institute, as the Weizmann for transplanting tissues; and the creation of a nanobiologi- Institute was originally called, was founded in 1934 by cal computer that may, in the future, be able to act directly Israel and Rebecca Sieff of the U.K., in memory of their inside the body to identify disease and eliminate it. son. The driving force behind its establishment was the Institute’s first president, Dr. Chaim Weizmann, a Today, the Institute is a leading force in advancing sci- noted chemist who headed the Zionist movement for ence education in all parts of society. Programs offered years and later became the first president of Israel. -

The Memory of the Yom Kippur War in Israeli Society

The Myth of Defeat: The Memory of the Yom Kippur War in Israeli Society CHARLES S. LIEBMAN The Yom Kippur War of October 1973 arouses an uncomfortable feeling among Israeli Jews. Many think of it as a disaster or a calamity. This is evident in references to the War in Israeli literature, or the way in which the War is recalled in the media, on the anniversary of its outbreak. 1 Whereas evidence ofthe gloom is easy to document, the reasons are more difficult to fathom. The Yom Kippur War can be described as failure or defeat by amassing one set of arguments but it can also be assessed as a great achievement by marshalling other sets of arguments. This article will first show why the arguments that have been offered in arriving at a negative assessment of the War are not conclusive and will demonstrate how the memory of the Yom Kippur War might have been transformed into an event to be recalled with satisfaction and pride. 2 This leads to the critical question: why has this not happened? The background to the Yom Kippur War, the battles and the outcome of the war, lend themselves to a variety of interpretations. 3 Since these are part of the problem which this article addresses, the author offers only the barest outline of events, avoiding insofar as it is possible, the adoption of one interpretive scheme or another. In 1973, Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish calendar, fell on Saturday, 6 October. On that day the Egyptians in the south and the Syrians in the north attacked Israel. -

Parries Hanna

637 Parries Hanna Horvitz & Horvitz Book & Nwsppr Agcy Leitner Benjamin Hadar Ins Co Ltd Mossenson Zipora & Amos Ricss Shalom (near Egged Bus Stn) . .70 97 Derech Karkur 74 83 56 Talmei Elazar 73 82 5 Shikun Rassco 72 26 Rifer Hana & Yehoshua Hospital Neve Shalvah Ltd 70 58 Lcnshitzki Shelomo Butchershop.. .72 67 Motro Samuel Car Dealer Rehov Harishonim Karkur 74 33 Levi Hermann & Lucie Rehov Harishonim 74 69 Robeosohn Dr Friedrich Rehov Ha'atzmaut Karkur 73 51 Mozes Walter Farmer Shekhunat Meged 70 30 Levit Abraham Devora & Thiya Rehov Habotnim 71 93 Robinson Abraham Derech Hanadiv71 18 Invalids Home Tel Alon Karkur 73 94 Mueller Sbelomit Rehov Hadekalim .70 34 Roichman Bros (Shomron) Ltd (near Meged) 72 83 Mahzevet Iron 74 43 Inwald F A Rehov Hanassi 73 95 Levy Otto Farmer Rehov Habotnim .72 09 Rosenau Chana Rehov Habotnim .74 79 Inwentash Josef Metal Wks Levy Tclma & Gad N Rosenbaum Dr Julius Phys Rehov Harishonim 74 36 Shechunat Rassco 21 74 24 Nachimovic Hava & Lipa Gan Hashomron 71 75 Iron Co-op Bakery Ltd Karkur .. .70 72 Lewi David Pension Kefar Pines . .73 40 Rehov Hapalmah 73 61 Rotenberg Abraham Agric Machs Lewin Ernst Jehuda Ishaky Dov Fuel & Lubr Stn Nadaf Rashid Mussa Farmer Moshav Talmei Elazar 71 12 Shekhunat Meged 72 56 Shikun Ammami 23 Karkur 73 29 Baqa El Gharbiya 71 53 Rubinstein Ami-Netzah Bet Olim D' .72 58 Liptscher Katricl & Menahem Crpntry Itin Shoshana & Ben-Zion Nattel Jacob Agcy of Carmei Oriental Rubinstein Hayim Derech Hanadiv . .71 50 Rehov Gilad 71 89 Rehov Hadekalim 70 94 Wines & Nesher Beer Lishkat Hammas Karkur 72 94 Itzkovits Aharon Car Elecn Rehov Haharuvim 72 69 S Pardes Hanna Rehov Hadkalim .70 73 Main Rd 74'40 Neumann Miriam & Kurt Local Council Baqa El Gharbiya 72 23 Sachs Dr Yehuda Gan Hashomron. -

Preserving Israel's Security Through a Two State Solution June 6, 18

Preserving Israel‘s Security through a Two State Solution Just 50 years ago, June 5-10, 1967, the Six-Day War took place, with consequences until today. Two high-ranking military experts of the Israeli Defense Forces - now active in the Peace and Security Association- are working to promote a sustainable political solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. June 6, 18:30h Diplomatic Academy of Vienna Favoritenstraße 15a, 1040 Vienna RSVP: www.da-vienna.ac.at/events Welcome: Amb. Hans Winkler (Director, Diplomatic Academy of Vienna) Keynote: Brig. Gen. (ret.) Gadi Zohar (Council of Peace and Security) Lt. Col. (res.) Ivri Verbin (Council of Peace and Security) Discussion: Gudrun Kramer (Director, Austrian Study Centre for Peace and Conflict Resolution/ASPR) Alan Freeman (New Israel Fund / NIF, Jerusalem) Moderator: Rubina Möhring (Présidente, Reporters Sans Frontières) Organizers: New Israel Fund (NIF), Austrian Chapter Peace and Security Association, Israel Partners and Diplomatic Academy of Vienna Co-Organizers: European Bureau for Policy Consulting and Social Research Vienna ICCR – The European Association for the Advancement of the Social Sciences Preserving Israel‘s Security through a Two State Solution Speaker Biographies Brig. Gen. (ret.) Gadi Zohar is the chairman of the Council for Peace and Security (CPS) since August 2013. Zohar served for more than 30 years in the Israeli Defense Forces. From 1991-1995, he was Head of the Civil Administration in the West Bank and during this time also served as a senior member of the Israeli delegation that negotiated the Gaza-Jericho Agreement. Prior to that, he was an intelligence attaché in the Israeli Embassy in Was- hington, founded and headed the Terror Department of the Intelligence Corp, and other intelligence posts. -

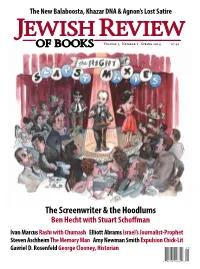

JEWISH REVIEW of BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95

The New Balaboosta, Khazar DNA & Agnon’s Lost Satire JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95 The Screenwriter & the Hoodlums Ben Hecht with Stuart Schoffman Ivan Marcus Rashi with Chumash Elliott Abrams Israel’s Journalist-Prophet Steven Aschheim The Memory Man Amy Newman Smith Expulsion Chick-Lit Gavriel D. Rosenfeld George Clooney, Historian NEW AT THE Editor CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY Abraham Socher Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Associate Editor Amy Newman Smith Administrative Assistant Rebecca Weiss Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Publisher Eric Cohen Associate Publisher & Director of Marketing Lori Dorr NEW SPACE The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, The David Berg Rare Book Room is a state-of- Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication the-art exhibition space preserving and dis- of ideas and criticism published in Spring, Summer, playing the written word, illuminating Jewish Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 165 East 56th Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10022. history over time and place. For all subscriptions, please visit www.jewishreviewofbooks.com or send $29.95 UPCOMING EXHIBITION ($39.95 outside of the U.S.) to Jewish Review of Books, Opening Sunday, March 16: By Dawn’s Early PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834. Please send notifi- cations of address changes to the same address or to Light: From Subjects to Citizens (presented by the [email protected]. -

The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017

The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017 Kenneth S. Brower Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 150 THE BEGIN-SADAT CENTER FOR STRATEGIC STUDIES BAR-ILAN UNIVERSITY Mideast Security and Policy Studies No. 150 The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017 Kenneth S. Brower The Israel Defense Forces, 1948-2017 Kenneth S. Brower © The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies Bar-Ilan University Ramat Gan 5290002 Israel Tel. 972-3-5318959 Fax. 972-3-5359195 [email protected] www.besacenter.org ISSN 0793-1042 May 2018 Cover image: Soldier from the elite Rimon Battalion participates in an all-night exercise in the Jordan Valley, photo by Staff Sergeant Alexi Rosenfeld, IDF Spokesperson’s Unit The Begin-Sadat (BESA) Center for Strategic Studies The Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies is an independent, non-partisan think tank conducting policy-relevant research on Middle Eastern and global strategic affairs, particularly as they relate to the national security and foreign policy of Israel and regional peace and stability. It is named in memory of Menachem Begin and Anwar Sadat, whose efforts in pursuing peace laid the cornerstone for conflict resolution in the Middle East. Mideast Security and Policy Studies serve as a forum for publication or re-publication of research conducted by BESA associates. Publication of a work by BESA signifies that it is deemed worthy of public consideration but does not imply endorsement of the author’s views or conclusions. Colloquia on Strategy and Diplomacy summarize the papers delivered at conferences and seminars held by the Center for the academic, military, official and general publics. -

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations Annemarie Randazzo-Matsel • Jennifer Schulte • Jennifer Yopp DIM-2012-U-000689-Final July 2012 Photo credit line: Young Israeli women undergo tough, initial pre-army training at Zikim Army Base in southern Israel. REUTERS/Nir Elias Approved for distribution: July 2012 Anita Hattiangadi Research Team Leader Marine Corps Manpower Team Resource Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Cleared for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 2012 CNA This work was created in the performance of Federal Government Contract Number N00014-11-D-0323. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in DFARS 252.227-7013 and/or DFARS 252.227-7014. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the read-ing or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. Contents Executive summary . 1 Foreign militaries . 3 Australia . 4 ADF composition . -

Israel and Overseas: Israeli Election Primer 2015 (As Of, January 27, 2015) Elections • in Israel, Elections for the Knesset A

Israel and Overseas: Israeli Election Primer 2015 (As of, January 27, 2015) Elections In Israel, elections for the Knesset are held at least every four years. As is frequently the case, the outgoing government coalition collapsed due to disagreements between the parties. As a result, the Knesset fell significantly short of seeing out its full four year term. Knesset elections in Israel will now be held on March 17, 2015, slightly over two years since the last time that this occurred. The Basics of the Israeli Electoral System All Israeli citizens above the age of 18 and currently in the country are eligible to vote. Voters simply select one political party. Votes are tallied and each party is then basically awarded the same percentage of Knesset seats as the percentage of votes that it received. So a party that wins 10% of total votes, receives 10% of the seats in the Knesset (In other words, they would win 12, out of a total of 120 seats). To discourage small parties, the law was recently amended and now the votes of any party that does not win at least 3.25% of the total (probably around 130,000 votes) are completely discarded and that party will not receive any seats. (Until recently, the “electoral threshold,” as it is known, was only 2%). For the upcoming elections, by January 29, each party must submit a numbered list of its candidates, which cannot later be altered. So a party that receives 10 seats will send to the Knesset the top 10 people listed on its pre-submitted list. -

IDF Special Forces – Reservists – Conscientious Objectors – Peace Activists – State Protection

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: ISR35545 Country: Israel Date: 23 October 2009 Keywords: Israel – Netanya – Suicide bombings – IDF special forces – Reservists – Conscientious objectors – Peace activists – State protection This response was prepared by the Research & Information Services Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. This research response may not, under any circumstance, be cited in a decision or any other document. Anyone wishing to use this information may only cite the primary source material contained herein. Questions 1. Please provide information on suicide bombs in 2000 to January 2002 in Netanya. 2. Deleted. 3. Please provide any information on recruitment of individuals to special army units for “chasing terrorists in neighbouring countries”, how often they would be called up, and repercussions for wanting to withdraw? 4. What evidence is there of repercussions from Israeli Jewish fanatics and Arabs or the military towards someone showing some pro-Palestinian sentiment (attending rallies, expressing sentiment, and helping Arabs get jobs)? Is there evidence there would be no state protection in the event of being harmed because of political opinions held? RESPONSE 1. Please provide information on suicide bombs in 2000 to January 2002 in Netanya. According to a 2006 journal article published in GeoJournal there were no suicide attacks in Netanya during the period of 1994-2000. No reports of suicide bombings in 2000 in Netanya were found in a search of other available sources.