Chapter 12 Gordon

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aliya Chalutzit from America, 1939-48

1 Aliya of American Pioneers By Yehuda Sela (Silverman) From Hebrew: Arye Malkin A) Aliya1 Attempts During WW II The members of the Ha‟Shomer Ha‟Tzair2 Zionist Youth Movement searched a long time for some means to get to the shores of the Land of Israel (Palestine). They all thought that making Aliya was preferable to joining the Canadian or the American Army, which would possibly have them fighting in some distant war, unrelated to Israel. Some of these efforts seem, in retrospect, unimaginable, or at least naïve. There were a number of discussions on this subject in the Secretariat of Kibbutz Aliya Gimel (hereafter: KAG) and the question raised was whether individual private attempts to make Aliya should be allowed. The problems were quite complicated, and rather than deciding against the effort to make Aliya, it was decided to allow these efforts in special cases. Later on the Secretariat decided against these private individual efforts. The members attempted several ways to pursue this goal, but none were successful. Some applied for a truck driver position with a company that operated in Persia, building roads to connect the Persian Gulf and the Caspian Sea. Naturally, holding a driving license that did not qualify one for heavy vehicles did not help. Another way was to volunteer to be an ambulance driver in the Middle East, an operation that was being run by the Quakers; this was a pacifist organization that had carried out this sort of work during the First World War. An organization called „The American Field Service‟ recruited its members from the higher levels of society. -

Project Aim and Objectives

1 MICROZONING OF THE EARTHQUAKE HAZARD IN ISRAEL PROJECT 9 SITE SPECIFIC EARTHQUAKE HAZARDS ASSESSMENT USING AMBIENT NOISE MEASUREMENTS IN HADERA, PARDES HANNA, BINYAMINA AND NEIGHBORING SETTLEMENTS November, 2009 Job No 526/473/09 Principal Investigator: Dr. Yuli Zaslavsky Collaborators G. Ataev, M. Gorstein, M. Kalmanovich, D. Giller, I. Dan, N. Perelman, T. Aksinenko, V. Giller, and A. Shvartsburg Submitted to: Earth Sciences Research Administration National Ministry of Infrastructures Contract Number: 28-17-054 2 CONTENT LIST OF FIGURES .......................................................................................................................... 3 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................................... 4 ABSTRACT ..................................................................................................................................... 5 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 7 Empirical approaches implemented in the analysis of site effect ................................................ 8 GEOLOGICAL OUTLINE ............................................................................................................ 10 Quaternary sediments ................................................................................................................. 12 Tertiary rocks ............................................................................................................................ -

Biographies Six Solo Exhibitions at Hagar Art Gallery, Jaffa Tal Ben Zvi Biographies Six Solo Exhibitions at Hagar Art Gallery, Jaffa

Biographies Six Solo Exhibitions at Hagar Art Gallery, Jaffa Tal Ben Zvi Biographies Six Solo Exhibitions at Hagar Art Gallery, Jaffa Curator, editor, text: Tal Ben Zvi Graphic Editing: Dina Shoham Graphic Design: Tal Stern Catalogue Production: Dina Shoham Studio English translation: Daria Kassovsky, Ela Bar-David (pp. E40-E47) Arabic translation: Roaa Translations Structure and language consultant: Gal N. Kusturica Special thanks to Asaf Zippor The curator wishes to thank Sami Abu Shehade and Ihsan Sirri who took part in the Gallery’s activity; the artists participating in this catalogue: David Adika, Anisa Ashkar, Hanna Farah, Tsibi Geva, Gaston Zvi Ickovicz, Khen Shish. Heartfelt thanks to Zahiya Kundos, Sami Buchari, Ela Bar-David, Ruthie Ginsburg, Lilach Hod, Hana Taragan, Tal Yahas, Shelly Cohen, Hadas Maor, Naama Meishar, Faten Nastas Mitwasi and Tali Rosin. Prepress: Kal Press Printing: Kal Press Binding: Sabag Bindery Published by Hagar Association, www.hagar-gallery.com No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, photocopied or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, or otherwise, without prior permission from the publishers. ISBN: 965-90953-1-7 Production of the catalogue was made possible through the support of: Israel National Lottery Council for the Arts The European Union Heinrich Böll Foundation © 2006, Tal Ben Zvi E5 Hagar Art Gallery, Jaffa Forgetting What Cannot be Forgotten Tal Ben Zvi E14 On Hanna Farah’s Distorted E19 On Tsibi Geva’s Lattice E23 On Gaston Zvi Ickowicz’s Buenos Aires E27 On Khen Shish’s Birthday E31 On David Adika’s Portraits: Mother Tongue E35 On Anisa Ashkar’s Barbur 24000 E40 Under the Light of Slumber Or, Hassan Beck’s Private Parking Zahiya Kundos E42 Aber Elr'ol Sami Buchari E48 CVs E51 List of Works Hagar Art Gallery, Jaffa Forgetting What Cannot be Forgotten | Tal Ben Zvi How could you stand life? These days we can stand it because of video; Abu Kamal was right – we’ve become a video nation. -

PPP Projects in Israel

PPP Projects in Israel Last update: January, 2021 PPP Projects in Israel 1) General Overview The current scope of infrastructure investment in the State of Israel is significantly lower than comparable PPP in Projects Israel countries around the world. This gap can be seen in traffic congestion and the low percentage of electricity production from renewable energy. Therefore, in 2017, Israel’s Minister of Finance appointed an inter-ministerial team to establish a national strategic plan in order to advance and expand investments in infrastructure projects. According to the team's conclusions, while in OECD countries the stock of economic infrastructure (transportation, water and energy) forms 71% of the GDP; in Israel it constitutes only 50% of the GDP. 1 PPP PROJECTS (Public Private Partnership) One of the main recommendations of the team was to substantially increase the investment in infrastructure by 2030. According to the team's evaluation, Such projects feature long-term where the present scope of infrastructure investments is maintained, the agreements between the State and a concessioner: the public sector existing gap from the rest of the world will further grow; in order to reach transfers to the private sector the the global average, a considerable increase of the infrastructure investments responsibility for providing a public in Israel is required through 2030. infrastructure, product or service, PPP in Projects Israel The team further recommended to, inter alia: develop a national including the design, construction, financing, operation and infrastructure strategy for Israel; improve statutory procedures; establish maintenance, in return for payments new financing tools for infrastructure investments and adjust regulation in based on predefined criteria. -

Parries Hanna

637 Parries Hanna Horvitz & Horvitz Book & Nwsppr Agcy Leitner Benjamin Hadar Ins Co Ltd Mossenson Zipora & Amos Ricss Shalom (near Egged Bus Stn) . .70 97 Derech Karkur 74 83 56 Talmei Elazar 73 82 5 Shikun Rassco 72 26 Rifer Hana & Yehoshua Hospital Neve Shalvah Ltd 70 58 Lcnshitzki Shelomo Butchershop.. .72 67 Motro Samuel Car Dealer Rehov Harishonim Karkur 74 33 Levi Hermann & Lucie Rehov Harishonim 74 69 Robeosohn Dr Friedrich Rehov Ha'atzmaut Karkur 73 51 Mozes Walter Farmer Shekhunat Meged 70 30 Levit Abraham Devora & Thiya Rehov Habotnim 71 93 Robinson Abraham Derech Hanadiv71 18 Invalids Home Tel Alon Karkur 73 94 Mueller Sbelomit Rehov Hadekalim .70 34 Roichman Bros (Shomron) Ltd (near Meged) 72 83 Mahzevet Iron 74 43 Inwald F A Rehov Hanassi 73 95 Levy Otto Farmer Rehov Habotnim .72 09 Rosenau Chana Rehov Habotnim .74 79 Inwentash Josef Metal Wks Levy Tclma & Gad N Rosenbaum Dr Julius Phys Rehov Harishonim 74 36 Shechunat Rassco 21 74 24 Nachimovic Hava & Lipa Gan Hashomron 71 75 Iron Co-op Bakery Ltd Karkur .. .70 72 Lewi David Pension Kefar Pines . .73 40 Rehov Hapalmah 73 61 Rotenberg Abraham Agric Machs Lewin Ernst Jehuda Ishaky Dov Fuel & Lubr Stn Nadaf Rashid Mussa Farmer Moshav Talmei Elazar 71 12 Shekhunat Meged 72 56 Shikun Ammami 23 Karkur 73 29 Baqa El Gharbiya 71 53 Rubinstein Ami-Netzah Bet Olim D' .72 58 Liptscher Katricl & Menahem Crpntry Itin Shoshana & Ben-Zion Nattel Jacob Agcy of Carmei Oriental Rubinstein Hayim Derech Hanadiv . .71 50 Rehov Gilad 71 89 Rehov Hadekalim 70 94 Wines & Nesher Beer Lishkat Hammas Karkur 72 94 Itzkovits Aharon Car Elecn Rehov Haharuvim 72 69 S Pardes Hanna Rehov Hadkalim .70 73 Main Rd 74'40 Neumann Miriam & Kurt Local Council Baqa El Gharbiya 72 23 Sachs Dr Yehuda Gan Hashomron. -

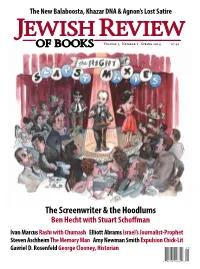

JEWISH REVIEW of BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95

The New Balaboosta, Khazar DNA & Agnon’s Lost Satire JEWISH REVIEW OF BOOKS Volume 5, Number 1 Spring 2014 $7.95 The Screenwriter & the Hoodlums Ben Hecht with Stuart Schoffman Ivan Marcus Rashi with Chumash Elliott Abrams Israel’s Journalist-Prophet Steven Aschheim The Memory Man Amy Newman Smith Expulsion Chick-Lit Gavriel D. Rosenfeld George Clooney, Historian NEW AT THE Editor CENTER FOR JEWISH HISTORY Abraham Socher Senior Contributing Editor Allan Arkush Art Director Betsy Klarfeld Associate Editor Amy Newman Smith Administrative Assistant Rebecca Weiss Editorial Board Robert Alter Shlomo Avineri Leora Batnitzky Ruth Gavison Moshe Halbertal Hillel Halkin Jon D. Levenson Anita Shapira Michael Walzer J. H.H. Weiler Leon Wieseltier Ruth R. Wisse Steven J. Zipperstein Publisher Eric Cohen Associate Publisher & Director of Marketing Lori Dorr NEW SPACE The Jewish Review of Books (Print ISSN 2153-1978, The David Berg Rare Book Room is a state-of- Online ISSN 2153-1994) is a quarterly publication the-art exhibition space preserving and dis- of ideas and criticism published in Spring, Summer, playing the written word, illuminating Jewish Fall, and Winter, by Bee.Ideas, LLC., 165 East 56th Street, 4th Floor, New York, NY 10022. history over time and place. For all subscriptions, please visit www.jewishreviewofbooks.com or send $29.95 UPCOMING EXHIBITION ($39.95 outside of the U.S.) to Jewish Review of Books, Opening Sunday, March 16: By Dawn’s Early PO Box 3000, Denville, NJ 07834. Please send notifi- cations of address changes to the same address or to Light: From Subjects to Citizens (presented by the [email protected]. -

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations

Assessing the Implications of Possible Changes to Women in Service Restrictions: Practices of Foreign Militaries and Other Organizations Annemarie Randazzo-Matsel • Jennifer Schulte • Jennifer Yopp DIM-2012-U-000689-Final July 2012 Photo credit line: Young Israeli women undergo tough, initial pre-army training at Zikim Army Base in southern Israel. REUTERS/Nir Elias Approved for distribution: July 2012 Anita Hattiangadi Research Team Leader Marine Corps Manpower Team Resource Analysis Division This document represents the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the Department of the Navy. Cleared for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Copyright 2012 CNA This work was created in the performance of Federal Government Contract Number N00014-11-D-0323. Any copyright in this work is subject to the Government's Unlimited Rights license as defined in DFARS 252.227-7013 and/or DFARS 252.227-7014. The reproduction of this work for commercial purposes is strictly prohibited. Nongovernmental users may copy and distribute this document in any medium, either commercially or noncommercially, provided that this copyright notice is reproduced in all copies. Nongovernmental users may not use technical measures to obstruct or control the read-ing or further copying of the copies they make or distribute. Nongovernmental users may not accept compensation of any manner in exchange for copies. All other rights reserved. Contents Executive summary . 1 Foreign militaries . 3 Australia . 4 ADF composition . -

Hagefen August 11, 2017

Hagefen www.gfn.co.il August 11, 2017 MENASHE SECTION Menashe Regional Council chair Ilan Sadeh signs the plan for the new industrial zone: Menashe Regional Council The Industrial Zone in Menashe: Planning completed for the Iron Industrial Zone The Menashe Regional Council has completed planning for the Iron Industrial Zone, with all approvals in hand Architect Leah Perry, engineer for the Menashe-Alona Regional Planning and Building Committee, noted that the land area chosen – part of the Menashe regional jurisdiction between the Menashe Regional Center and the Barkai intersection – is close to the country’s main transportation network, in proximity to the Iron interchange on Trans-Israel Highway 6 as well as Highway 2, Route 65 and Israel Railways. The location is also consonant with the master plan for Wadi Ara development. The industrial zone has a total area of 1085 dunams (c. 268 acres), with 628,000 square meters for industrial and commercial buildings and another c. 15,000 square meters of public buildings. by Yaniv Golan This week Menashe Regional Council chairman Ilan Sadeh and architect Leah Perry, the council engineer for the Menashe-Alona Regional Planning and Building Committee, signed off on the plans, which were forwarded for registration with the Haifa District Planning and Building Committee, prior to final approval of the plans. The Iron Industrial Zone will be shared by six Jewish and Arab local councils in the northern Sharon area of Wadi Ara. The new industrial zone is an initiative of Menashe Regional Council chairman Ilan Sadeh. Behind this project is a unique Jewish-Arab partnership involving Jewish councils – the Menashe regional council and the Harish local council – alongside a series of Arab councils in Wadi Ara – the Umm al Fahm municipality, the Kfar Qara local council, the Basma local council (comprising Barta’a, Ein a-Sahle and Muawiya) and the Arara local council. -

Patterns of Immigration and Absorption

Patterns of Immigration and Absorption Aviva Zeltzer-Zubida Ph.D. [email protected] Director of Research, Evaluation and Measurement, Strategy and Planning Unit The Jewish Agency for Israel Hani Zubida Ph.D. [email protected] Department of Political Science The Max Stern Yezreel Valley College May 2012 1. Introduction Throughout the course of its modern history, Israel has been perceived as an immigration state. From the first days of the ―new Yishuv,‖ at the end of the nineteenth century, the development of the Jewish society in Palestine has been dependent on immigration, first from Eastern European countries, later from Central Europe and, immediately after the establishment of the state in 1948, from the Middle East. The centrality of immigration to the reality of Israel, to the nation, to the Israeli society, and to the Jews who came, can be appreciated from the Hebrew word coined to describe it, ―aliyah,‖ which means ascending, but this is much more than just verbal symbolism. Immigration to Israel, that is, aliyah, in effect implies rising above one‘s former status to assert one‘s Jewish citizenship and identity. Jewish ius sanguinis1 thus trumped all other issues of status and identity (Harper and Zubida, 2010). As such, there are never “immigrants” to Israel, but only Jews returning home, asserting their true identity and, as codified in Israel‘s right of return and citizenship laws, their legitimate claim to residence and citizenship. Thus, by this logic, Israel is not an immigration state, but is rather the homeland of the Jewish People. In this article we start with a survey of the major waves of immigration to Israel dating back to the pre-state era and review the characteristics of the various groups of immigrants based on earlier studies. -

My Life's Story

My Life’s Story By Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz 1915-2000 Biography of Lieutenant Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Z”L , the son of Rabbi Moshe Mordechai Shwartz Z”L , and Rivka Shwartz, née Klein Z”L Gilad Jacob Joseph Gevaryahu Editor and Footnote Author David H. Wiener Editor, English Edition 2005 Merion Station, Pennsylvania This book was published by the Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz Memorial Committee. Copyright © 2005 Yona Shwartz & Gilad J. Gevaryahu Printed in Jerusalem Alon Printing 02-5388938 Editor’s Introduction Every Shabbat morning, upon entering Lower Merion Synagogue, an Orthodox congregation on the outskirts of the city of Philadelphia, I began by exchanging greetings with the late Lt. Colonel Eliyahu Yekutiel Shwartz. He used to give me news clippings and booklets which, in his opinion, would enhance my knowledge. I, in turn, would express my personal views on current events, especially related to our shared birthplace, Jerusalem. Throughout the years we had an unwritten agreement; Eliyahu would have someone at the Israeli Consulate of Philadelphia fax the latest news in Hebrew to my office (Eliyahu had no fax machine at the time), and I would deliver the weekly accumulation of faxes to his house on Friday afternoons before Shabbat. This arrangement lasted for years. Eliyahu read the news, and distributed the material he thought was important to other Israelis and especially to our mutual friend Dr. Michael Toaff. We all had an inherent need to know exactly what was happening in Israel. Often, during my frequent visits to Israel, I found that I was more current on happenings in Israel than the local Israelis. -

'Strategy and Iran Directorate' Under General Staff

MIDDLE EAST, NORTH AFRICA Israel Establishes New ‘Strategy and Iran Directorate’ Under General Staff OE Watch Commentary: On 18 February, the Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) announced the creation of a new directorate within the General Staff, called the “Strategy and Iran Directorate” to address growing Iranian threats and coordinate actions against Iran under one roof. The accompanying passages from local sources discuss this new directorate and subsequent changes to the structure of the IDF. The first article from The Times of Israel describes the design of the new Iran Directorate. Currently, the IDF has Major General Amir Baram leading the Northern Command in overseeing operations and threats stemming from Hezbollah while Major General Herzi Halevi and the Southern Command oversee the fight against Hamas in the Gaza Strip. Similarly, the IDF will now have a major general overseeing operations and threats coming directly from Iran. This means that the responsibility for overseeing threats from and actions towards Israel Defense Forces - Nahal’s Brigade Wide Drill. Iran is split between multiple different sections of the Israeli Military such as Source: Flickr via Wikimedia, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flickr_-_Israel_Defense_Forces_-_Nahal%27s_ Brigade_Wide_Drill_(1).jpg, CC BY 3.0 the Air Force, the Operations Directorate, the Planning Directorate, and Military Intelligence. The second article from The Times of Israel states the Strategy and Iran Directorate will not be responsible for overseeing threats from Iranian proxy forces but only Iran itself, even though Iran has ties to multiple organizations across the region. It reports that the directorate “will be responsible for countering Iran only, not its proxies, like the Hezbollah terror group, which will remain the purview of the IDF Northern Command.” Brigadier General Tal Kalman, currently in charge of the IDF’s Strategic Division, will be promoted to major general and will lead the Strategy and Iran Directorate. -

1948 Arab‒Israeli

1948 Arab–Israeli War 1 1948 Arab–Israeli War מלחמת or מלחמת העצמאות :The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, known to Israelis as the War of Independence (Hebrew ,מלחמת השחרור :, Milkhemet Ha'atzma'ut or Milkhemet HA'sikhror) or War of Liberation (Hebrewהשחרור Milkhemet Hashikhrur) – was the first in a series of wars fought between the State of Israel and its Arab neighbours in the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict. The war commenced upon the termination of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Israeli declaration of independence on 15 May 1948, following a period of civil war in 1947–1948. The fighting took place mostly on the former territory of the British Mandate and for a short time also in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.[1] ., al-Nakba) occurred amidst this warﺍﻟﻨﻜﺒﺔ :Much of what Arabs refer to as The Catastrophe (Arabic The war concluded with the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Background Following World War II, on May 14, 1948, the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end. The surrounding Arab nations were also emerging from colonial rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan, but it remained under heavy British influence. Egypt, while nominally independent, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that included provisions by which Britain would maintain a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal. From 1945 on, Egypt attempted to renegotiate the terms of this treaty, which was viewed as a humiliating vestige of colonialism. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops would not withdraw until 1946, the same year that Syria won its independence from France.