Thesis I. Seed Dispersal by the Critically Endangered Alala

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Urera Kaalae

Plants Opuhe Urera kaalae SPECIES STATUS: Federally Listed as Endangered Genetic Safety Net Species J.K.Obata©Smithsonian Inst., 2005 IUCN Red List Ranking – Critically Endangered (CR D) Hawai‘i Natural Heritage Ranking ‐ Critically Imperiled (G1) Endemism – O‘ahu Critical Habitat ‐ Designated SPECIES INFORMATION: Urera kaalae, a long‐lived perennial member of the nettle family (Urticaceae), is a small tree or shrub 3 to 7 m (10 to 23 ft) tall. This species can be distinguished from the other Hawaiian species of the genus by its heart‐shaped leaves. DISTRIBUTION: Found in the central to southern parts of the Wai‘anae Mountains on O‘ahu. ABUNDANCE: The nine remaining subpopulations comprise approximately 40 plants. LOCATION AND CONDITION OF KEY HABITAT: Urera kaalae typically grows on slopes and in gulches in diverse mesic forest at elevations of 439 to 1,074 m (1,440 to 3,523 ft). The last 12 known occurrences are found on both state and privately owned land. Associated native species include Alyxia oliviformis, Antidesma platyphyllum, Asplenium kaulfusii, Athyrium sp., Canavalia sp., Charpentiera sp., Chamaesyce sp., Claoxylon sandwicense, Diospyros hillebrandii, Doryopteris sp., Freycinetia arborea, Hedyotis acuminata, Hibiscus sp., Nestegis sandwicensis, Pipturus albidus, Pleomele sp., Pouteria sandwicensis, Psychotria sp., Senna gaudichaudii (kolomona), Streblus pendulinus, Urera glabra, and Xylosma hawaiiense. THREATS: Habitat degradation by feral pigs; Competition from alien plant species; Stochastic extinction; Reduced reproductive vigor due to the small number of remaining individuals. CONSERVATION ACTIONS: The goals of conservation actions are not only to protect current populations, but also to establish new populations to reduce the risk of extinction. -

Field Instructions for The

FIELD INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE INVENTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS 2013 Hawaii Edition Forest Inventory and Analysis Program Pacific Northwest Research Station USDA Forest Service THIS MANUAL IS BASED ON: FOREST INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS NATIONAL CORE FIELD GUIDE FIELD DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES FOR PHASE 2 PLOTS VERSION 5.1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................ 1 1.1 PURPOSES OF THIS MANUAL ................................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 ORGANIZATION OF THIS MANUAL .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2.1 UNITS OF MEASURE ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 1.2.2 GENERAL DESCRIPTION ............................................................................................................................................................ 2 1.2.3 PLOT SETUP .............................................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.2.4 PLOT INTEGRITY ...................................................................................................................................................................... -

Auwahi: Ethnobotany of a Hawaiian Dryland Forest

AUWAHI: ETHNOBOTANY OF A HAWAIIAN DRYLAND FOREST. A. C. Medeiros1, C.F. Davenport2, and C.G. Chimera1 1. U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Haleakala Field Station, P.O. Box 369, Makawao, HI 96768 2. Social Sciences Department, Maui Community College, 310 Ka’ahumanu Ave., Kahului, HI 96732 ABSTRACT Auwahi district on East Maui extends from sea level to about 6800 feet (1790 meters) elevation at the southwest rift of leeward Haleakal¯a volcano. In botanical references, Auwahi currently refers to a centrally located, fairly large (5400 acres) stand of diverse dry forest at 3000-5000 feet (915- 1525 meters) elevation surrounded by less diverse forest and more open-statured shrubland on lava. Auwahi contains high native tree diversity with 50 dryland species, many with extremely hard, durable, and heavy wood. To early Hawaiians, forests like Auwahi must have seemed an invaluable source of unique natural materials, especially the wide variety of woods for tool making for agriculture and fishing, canoe building, kapa making, and weapons. Of the 50 species of native trees at Auwahi, 19 species (38%) are known to have been used for medicine, 13 species (26%) for tool-making, 13 species (26%) for canoe building 13 species (26%) for house building, 8 species (16%) for tools for making kapa, 8 species (16%) for weapons 8 species (16%) for fishing, 8 species (16%) for dyes, and 7 species (14 %) for religious purposes. Other miscellaneous uses include edible fruits or seeds, bird lime, cordage, a fish narcotizing agent, firewood, a source of "fireworks", recreation, scenting agents, poi boards, and h¯olua sled construction. -

5-YEAR REVIEW Short Form Summary Species Reviewed: Pteralyxia Kauaiensis (Kaulu) Curre Nt Classification: Endangered

5-YEAR REVIEW Short Form Summary Species Reviewed: Pteralyxia kauaiensis (kaulu) Curre nt Classification: Endangered Federal Register Notice announcing initiation of this review: [USFWS] U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2008. Endangered and threatened wildlife and plants; initiation of 5-year status reviews of 70 species in Idaho, Montana, Oregon, Washington, and the Pacific Islands. Federal Register 73(83):23264- 23266. Lead Region/Field Office: Re gio n 1 /Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, Honolulu, Hawaii Name of Reviewer(s): Marie Bruegmann, Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, Plant Recovery Coordinator Marilet A. Zablan, Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, Assistant Field Supervisor for Endangered Species Jeff Newman, Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office, Acting Deputy Field Supervisor Methodology used to complete this 5-year review: This review was conducted by staff of the Pacific Islands Fish and Wildlife Office of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), beginning on April 29, 2008. The review was based on the final critical habitat designation for Pteralyxia kauaiensis and other species from the island of Kauai (USFWS 2003), as well as a review of current, available information. The National Tropical Botanical Garden provided an initial draft of portions of the review and recommendations for conservation actions needed prior to the next five-year review. The evaluation of Samuel Aruch, biological consultant, was reviewed by the P lant Recovery Coordinator. The document was then reviewed by the Assistant Field Supervisor for Endangered Species and Acting Deputy Field Supervisor before submission to the Field Supervisor for approval. Background: For information regarding the species listing history and other facts, please refer to the Fish and Wildlife Service’s Environmental Conservation On-line System (ECOS) database for threatened and endangered species (http://ecos.fws.gov/tess_public). -

Delissea Subcordata

Plants ‘Oha Delissea subcordata SPECIES STATUS: Federally Listed as Endangered Genetic Safety Net Species John K. Obata © Smithsonian Inst., 2005 Hawai‘i Natural Heritage Ranking ‐ Critically Imperiled (G1) Endemism – O‘ahu Critical Habitat ‐ Designated SPECIES INFORMATION: Delissea subcordata, a member of the bellflower family (Campanulaceae), is a branched or unbranched shrub 1 ‐ 3 m tall. Leaves ovate or ovate‐ lanceolate, blades 12 ‐ 30 cm long, 6 ‐ 17 cm wide, margins crenate, denticulate, serrate, or doubly serrate, the teeth incurved, or occasionally irregularly laciniate with 1 ‐ 6 triangular lobes 10 ‐ 18 mm long toward the base, apex obtuse, acute, or acuminate, base cordate, subcordate, or truncate, petioles 6 ‐ 18 cm long. Inflorescences 6 ‐ 18 flowered, glabrous, peduncles 40 ‐ 100 mm long, pedicels 13 ‐ 18 mm long; hypanthium ovoid to cylindrical; calyx lobes subulate, 0.5 ‐ 1 mm long; corolla white or greenish white, curved, 45 ‐ 60 mm long, with 1 dorsal knob; anthers glabrous. Berries ovoid, 12 ‐16 mm long, 8 ‐ 12 mm in diameter. Seeds ca. 1 mm long. Occurring in diverse mesic forest, 250 ‐ 400 m, Ko‘olau Mountains, and 450 ‐ 550 m, Wai‘anae Mountains, O‘ahu. DISTRIBUTION: The persistence of this plant in the Wai‘anae Mountains is well documented. However, it has not been collected in the Ko‘olau Mountains since 1934 and may be extinct there. ABUNDANCE: Currently 60‐70 plants observed. Delissea subcordata is now known only from the Wai‘anae Mountains in nine populations distributed from Kawaiu Gulch in the Kealia land section in the northern Wai‘anae Mountains to the north branch of North Palawai Gulch about 20 km (12 mi) to the south. -

Honolulu, Hawaii 96822

COOPERATNE NATIONAL PARK FEmFas SIUDIES UNIT UNIVERSI'IY OF -1 AT MANQA Departmerrt of Botany 3190 Maile Way Honolulu, Hawaii 96822 (808) 948-8218 --- --- 551-1247 IFIS) - - - - - - Cliffod W. Smith, Unit Director Professor of Botany ~echnicalReport 64 C!HECXLI:ST OF VASaTLAR mANIS OF HAWAII VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK Paul K. Higashino, Linda W. Cuddihy, Stephen J. Anderson, and Charles P. Stone August 1988 clacmiIST OF VASCULAR PLANrs OF HAWAII VOLCANOES NATIONAL PARK The following checMist is a campilation of all previous lists of plants for Hawaii Volcanoes National Park (HAVO) since that published by Fagerlund and Mitchell (1944). Also included are observations not found in earlier lists. The current checklist contains names from Fagerlund and Mitchell (1944) , Fagerlund (1947), Stone (1959), Doty and Mueller-Dambois (1966), and Fosberg (1975), as well as listings taken fram collections in the Research Herbarium of HAVO and from studies of specific areas in the Park. The current existence in the Park of many of the listed taxa has not been confirmed (particularly ornamentals and ruderals). Plants listed by previous authors were generally accepted and included even if their location in HAVO is unknown to the present authors. Exceptions are a few native species erroneously included on previous HAVO checklists, but now known to be based on collections from elsewhere on the Island. Other omissions on the current list are plant names considered by St. John (1973) to be synonyms of other listed taxa. The most recent comprehensive vascular plant list for HAVO was done in 1966 (Ihty and Mueller-Dombois 1966). In the 22 years since then, changes in the Park boundaries as well as growth in botanical knowledge of the area have necessitated an updated checklist. -

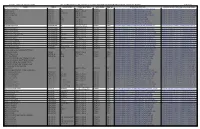

Mapping Plant Species Ranges in the Hawaiian Islands—Developing A

Filename: of2012-1192_appendix-table.pdf Note: An explanation of this table and its contents is available at http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/of2012-1192_appendix-table-guide.pdf Page 1 of 22 NAME FAMILY Common Name Conservation Status Native Status Map Type DOWNLOAD JPG FILES DOWNLOAD GIS FILES (shapefiles, in zip format) Abutilon eremitopetalum Malvaceae n/a Endangered Endemic Model http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/jpgs/Abutilon_eremitopetalum.jpg http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/shapefiles/abuerem.zip Abutilon incanum Malvaceae Ma‘o Apparently Secure Indigenous Model http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/jpgs/Abutilon_incanum.jpg http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/shapefiles/abuinca.zip Abutilon menziesii Malvaceae Ko‘oloa ‘ula Endangered Endemic Model http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/jpgs/Abutilon_menziesii.jpg http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/shapefiles/abumenz.zip Abutilon sandwicense Malvaceae n/a Endangered Endemic Model http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/jpgs/Abutilon_sandwicense.jpg http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/shapefiles/abusand.zip Acacia koa Fabaceae Koa Apparently Secure Endemic Model http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/jpgs/Acacia_koa.jpg http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/shapefiles/acakoa.zip Acacia koaia Fabaceae Koai‘a Vulnerable Endemic Model http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/jpgs/Acacia_koaia.jpg http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/shapefiles/acakoai.zip Acaena exigua Rosaceae Liliwai Endangered Endemic Model http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/jpgs/Acaena_exigua.jpg http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1192/shapefiles/acaexig.zip -

Revised List of Hawaiian Names of Plants Native and Introduced with Brief Descriptions and Notes As to Occurrence and Medicinal Or Other Values

Revised List of Hawaiian Names of Plants Native and Introduced with Brief Descriptions and Notes as to Occurrence and Medicinal or Other Values by Joseph F. Rock Consulting Botanist, Board of Agriculture and Forestry Honolulu, Hawai‘i, 1920 Transcribed and annotated by Samuel M. ‘Ohukani‘ōhi‘a Gon III Introduction to the 1920 Manuscript In 1913, the writer compiled a list of Hawaiian names of knowledge of the Hawaiian language the writer will leave plants, which was published as Botanical Bulletin No. for Hawaiian scholars, such as Mr. T.C. Thrum and Mr. 2 of the Board of Agriculture and Forestry. The above Joseph Emerson, and it is hoped that in the compilation mentioned list comprised simply the Hawaiian names of the new Hawaiian Dictionary, provision for which was and the corresponding scientific names of plants both made by the Hawaiian Legislature, the Hawaiian names native and introduced. Owing to the popularity of, and the given in this publication will not only be used, but their demand for, the bulletin it was soon out of print, and the original meaning explained in order to preserve the historic suggestion was made by the Superintendent of Forestry value connected with them. No name was inserted for that the list be reprinted. Since 1913, the writer has added which the writer did not have the actual corresponding quite a number of new names to the old list and it was plant before him. Some of the plants brought to him by thought advisable to incorporate these in the present kahunas were fragmentary and a specific diagnosis could publication, which gives in addition a short popular not be made owing to the polymorphic character of many description of the plants and such facts and notes as are of the Hawaiian plants, especially such as belong to of ethnological and historical interest. -

Maui County Planting Plan Third Edition

MAUI COUNTY PLANTING PLAN THIRD EDITION Maui County Arborist Committee MAUI COUNTY PLANTING PLAN—THIRD EDITION IT’S ALL ABOUT SHADE! UH Maui College Science Parking Lot, E. H. Rezents photograph, taken January 2011. This document has been researched, written and coordinated for the Maui County Arborist Committee By Ernest H. Rezents Professor Emeritus Agriculture, University of Hawaii Maui College Certified Arborist, International Society of Arboriculture Registered Consulting Arborist, American Society of Consulting Arborists September 1, 1991, First Edition July 20, 1994, Second Edition December 2000, Second Edition Reprinted March 9, 2016, Third Edition Maui County Planting Plan—Third Edition MAUI COUNTY ARBORIST COMMITTEE – 2016 Kimberly Thayer, Chair Heather A. K. Heath, Vice Chair Jackie Brainard Casey A. Foster, ISA* Certified Arborist Alex Haller William G. Jacintho, ISA* Certified Arborist William R. Myrter Jean A. Pezzoli, PhD Chris Reynolds Ex-Officio Members Maui County Corporation Council Maui County Parks and Recreation Department Maui County Planning Department Maui County Public Works Department Maui County Water Department Maui County Arborist *International Society of Arboriculture Maui County Planting Plan—Third Edition MAYOR'S MESSAGE Maui County Planting Plan—Third Edition ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author wishes to thank the following individuals and organizations for their support and contributions that made possible the publication of the Maui County Planting Plan. Robert (Bob) Hobdy for his assistance with plant scientific names and characteristics, exceptional tree research, and the Maui County Island maps with planting zones. Philip Thomas, a former Database Administrator with the Hawaii Ecosystems at Risk project (HEAR), for assisting with plant database storage and formatting chapter tables. -

PACIFIC ISLANDS PNW-FIADB User's Manual

PACIFIC ISLANDS PNW-FIADB User’s Manual A data dictionary and user guide for the Pacific Islands PNW-FIADB database Inventory Data for the Pacific Islands The Pacific Northwest Forest Inventory and Analysis Database The database includes data for: America Samoa Guam Palau Hawaii (documented here; data to be compiled in 2015) For more information or help, please contact : Olaf Kuegler 503-808-2028 [email protected] Jane Reid 907-743-9411 [email protected] Ashley Lehman 907-743-9415 [email protected] Sharon Stanton 503-808-2019 [email protected] Forest Inventory and Analysis Pacific Northwest Research Station Portland, Oregon This documentation is based on the National FIADB manual A customized version for the Pacific Northwest FIA program Foreword The mission of Forest Inventory and Analysis (FIA) is to determine the status and trend in forest resources. FIA is a continuing endeavor mandated by Congress in the Forest and Rangeland Renewable Resources Planning Act of 1974 and the McSweeney‐McNary Forest Research Act of 1928. The USDA Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station is responsible for conducting inventories in the U.S. affiliated Pacific Islands. Specifically, the Forest Inventory and Analysis program within the Resource Monitoring and Assessment Program (known as RMA‐FIA), collects data in cooperation and collaboration with Island governments, land owners, and citizens; compiles data and creates databases for distribution to the public; and publishes summary reports to document and interpret the information. The island groups inventoried by RMA‐FIA include American Samoa, Guam, Hawaii, the Republic of Palau, the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and the Republic of the Marshall Islands. -

Field Instructions for the Periodic Inventory Of

FIELD INSTRUCTIONS FOR THE PERIODIC INVENTORY OF FEDERATED STATES OF MICRONESIA 2016 FOREST INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS RESOURCE MONITORING AND ASSESSMENT PROGRAM PACIFIC NORTHWEST RESEARCH STATION USDA FOREST SERVICE THIS MANUAL IS BASED ON: FOREST INVENTORY AND ANALYSIS NATIONAL CORE FIELD GUIDE VOLUME I: FIELD DATA COLLECTION PROCEDURES VERSION 7.0 Cover image by Gretchen Bracher pg.I Table of Contents CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION . 13 SECTION 1.1 ORGANIZATION OF THIS MANUAL. 13 SECTION 1.2 THE INVENTORY. 14 SECTION 1.3 PRODUCTS . 14 SECTION 1.4 UNITS OF MEASURE . 14 SECTION 1.5 PLOT DESIGN GENERAL DESCRIPTION . 14 SUBSECTION 1.5.1 PLOT LAYOUT . .15 SUBSECTION 1.5.2 DATA ARE COLLECTED ON PLOTS AT THE FOLLOWING LEVELS .15 SECTION 1.6 QUALITY ASSURANCE/QUALITY CONTROL . 16 SUBSECTION 1.6.1 GENERAL DESCRIPTION . .16 SECTION 1.7 SAFETY . 16 SUBSECTION 1.7.1 SAFETY IN THE WOODS. .16 SUBSECTION 1.7.2 SAFETY ON THE ROAD . .17 SUBSECTION 1.7.3 WHAT TO DO IF INJURED. .17 CHAPTER 2 LOCATING THE PLOT . 19 SECTION 2.1 LOCATING AN ESTABLISHED PLOT . 19 SUBSECTION 2.1.1 NAVIGATING WITH PHOTOGRAPHY. .19 SUBSECTION 2.1.2 NAVIGATING WITH GPS . .19 SUBSECTION 2.1.3 NAVIGATING WITH REFERENCE POINT (RP) DATA . .20 SUBSECTION 2.1.4 REVERSE REFERENCE POINT (RP) METHOD . .20 SECTION 2.2 ESTABLISHED PLOT ISSUES . 20 SUBSECTION 2.2.1 DIFFICULTY FINDING ESTABLISHED PLOTS. 20 SUBSECTION 2.2.2 INCORRECTLY INSTALLED PLOT . .21 SUBSECTION 2.2.3 INCORRECTLY INSTALLED SUBPLOT OR MICROPLOT. .21 SUBSECTION 2.2.4 PC STAKE OR SUBPLOT/MICROPLOT PIN MISSING OR MOVED . -

Plants to Control Stream Bank Erosion

WAIMANALO WATERSHED RESTORATION PROJECT plants to control stream bank erosion Is there an erosion problem along your section of the stream? If the erosion problem is not too severe, and your slope is 2:1 or less, planting a combination of shrubs and trees can often help protect stream banks. The Waimanalo Watershed Project has been using native plants with encouraging results on Waimanalo Stream. Check out our plantings next to Weinberg Village (Kahawai Stream) and at the bridge on Saddle City Road (Waimanalo Stream). ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ Sources of Pick the Right Plant Plant Materials Use the table inside for suggestions for native plants for your stream side project. Take into account the sunlight and water conditions of Home Depot your site. Purchase healthy container stock from a local nursery. Hui Ku Maoli Ola Native Hawaiian Plant Specialists Planting Out phone: 259-6580 Make the planting hole twice as wide as the root ball and just as Native Plant Source deep. If the soil is clay-like and drains slowly, mix in some coarse phone: 227-2019 red or black cinder, and coarse perlite or compost. Carefully remove the plant from the container and place it in the BOOKS with More Info hole without bending the roots into a “J” shape. Fill the hole back up on Native Plants so the top of the soil is at the same level as the top of the potting mix. Don’t bury the stem or leave roots exposed to air. Growing Native Hawaiian Water thoroughly after you transplant. Plants by Heidi Bornhorst Mulch A Native Hawaiian Garden Place a layer of mulch around your plants to conserve water, re- by John L.