Overview of Hawaiian Dry Forest Propagation Techniques

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Ala'alahua, Mahoe

Plants ʹAlaʹalahua, mahoe Alectryon macrococcus var. auwahiensis SPECIES STATUS: Federally Listed as Endangered Genetic Safety Net Species IUCN Red List Ranking ‐ CR B2ab(i,ii,iii,iv,v) Hawai‘i Natural Heritage Ranking ‐ Critically Imperiled (G1T1) Endemism ‐ Maui Kim and Forest Starr, USGS Critical Habitat ‐ Designated SPECIES INFORMATION: Alectryon macrococcus of the soapberry family (Sapindaceae) is a tree up to 36 ft (11 m) tall with reddish brown branches. The leaves are usually 8 to 22 in (20 to 55 cm) long, typically with two to five pairs of egg‐shaped, slightly asymmetrical leaflets. Glossy and smooth above, the leaves have a conspicuous netted pattern of veins. A dense covering of rust‐colored hairs persists on the lower surfaces of mature leaves of A. macrococcus var. auwahiensis, whereas the mature leaves of A. macrococcus var. macrococcus lack hairs or are only slightly hairy. In both varieties, the flowers, which may be either bisexual or male, are borne in branched clusters up to l2 in (30 cm) long and lack petals. The fruit of this tree provided food for the early Hawaiians, as both the seed and the scarlet‐colored, fleshy aril around it have mild but slightly sweet flavors. The two varieties recognized for this species are Federally Listed as Endangered. The first, variety macrococcus, is found on four Hawaiian islands. The second, discussed here, is variety auwahiensis, found only on the island of Maui, and is much rarer. DISTRIBUTION: A. macrococcus var. auwahiensis is found only on the island of Maui, on the south slope of the volcano Haleakalā, at elevations of 1,017 and 3,562 m (1,168 and 3,337 ft). -

(Rattus Spp. and Mus Musculus) in The

CHAPTER SIX: CONCLUSIONS Aaron B. Shiels Department of Botany University of Hawaii at Manoa 3190 Maile Way Honolulu, HI. 96822 173 Along with humans, introduced rats (Rattus rattus, R. norvegicus, and R. exulans) and mice (Mus musculus) are among the most invasive and widely distributed mammals on the planet; they occur on more than 80% of the world‘s islands groups (Atkinson 1985; Towns 2009). By incorporating modern technology, such as aerial broadcast of rodenticides, the number of islands where invasive rodents can be successfully removed has recently increased (Howald et al. 2007). However, successful rat and mouse eradication on relatively large (> 5000 ha) or human-inhabited islands such as the main Hawaiian Islands rarely occurs (Howald et al. 2007) despite large sums of money and research efforts annually to combat invasive rodent problems (see Chapter 1 section ―Rat history in Hawaii‖; Tobin et al. 1990). Therefore, it is highly unlikely that invasive rats and mice will be eradicated from relatively large, human-occupied islands such as Oahu in the near or distant future (Howald et al. 2007); and accepting this may be a first step towards increasing the likelihood of native species conservation in archipelagos like Hawaii where introduced rodents have established. Determining which invasive rodent species are present at a given site is important because the risks that some rodent species pose to particular (prey) species and/or habitats differ from those posed by other rodent species. Two sympatric species cannot occupy the same niche indefinitely, in a stable environment (Gause 1934), which may partly explain why some rodent species may not occur where others are present (Harper 2006). -

Pu'u Wa'awa'a Biological Assessment

PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A, NORTH KONA, HAWAII Prepared by: Jon G. Giffin Forestry & Wildlife Manager August 2003 STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF FORESTRY AND WILDLIFE TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE ................................................................................................................................. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. ii GENERAL SETTING...................................................................................................................1 Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Land Use Practices...............................................................................................................1 Geology..................................................................................................................................3 Lava Flows............................................................................................................................5 Lava Tubes ...........................................................................................................................5 Cinder Cones ........................................................................................................................7 Soils .......................................................................................................................................9 -

Urera Kaalae

Plants Opuhe Urera kaalae SPECIES STATUS: Federally Listed as Endangered Genetic Safety Net Species J.K.Obata©Smithsonian Inst., 2005 IUCN Red List Ranking – Critically Endangered (CR D) Hawai‘i Natural Heritage Ranking ‐ Critically Imperiled (G1) Endemism – O‘ahu Critical Habitat ‐ Designated SPECIES INFORMATION: Urera kaalae, a long‐lived perennial member of the nettle family (Urticaceae), is a small tree or shrub 3 to 7 m (10 to 23 ft) tall. This species can be distinguished from the other Hawaiian species of the genus by its heart‐shaped leaves. DISTRIBUTION: Found in the central to southern parts of the Wai‘anae Mountains on O‘ahu. ABUNDANCE: The nine remaining subpopulations comprise approximately 40 plants. LOCATION AND CONDITION OF KEY HABITAT: Urera kaalae typically grows on slopes and in gulches in diverse mesic forest at elevations of 439 to 1,074 m (1,440 to 3,523 ft). The last 12 known occurrences are found on both state and privately owned land. Associated native species include Alyxia oliviformis, Antidesma platyphyllum, Asplenium kaulfusii, Athyrium sp., Canavalia sp., Charpentiera sp., Chamaesyce sp., Claoxylon sandwicense, Diospyros hillebrandii, Doryopteris sp., Freycinetia arborea, Hedyotis acuminata, Hibiscus sp., Nestegis sandwicensis, Pipturus albidus, Pleomele sp., Pouteria sandwicensis, Psychotria sp., Senna gaudichaudii (kolomona), Streblus pendulinus, Urera glabra, and Xylosma hawaiiense. THREATS: Habitat degradation by feral pigs; Competition from alien plant species; Stochastic extinction; Reduced reproductive vigor due to the small number of remaining individuals. CONSERVATION ACTIONS: The goals of conservation actions are not only to protect current populations, but also to establish new populations to reduce the risk of extinction. -

Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service

Thursday, February 27, 2003 Part II Department of the Interior Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Final Designation or Nondesignation of Critical Habitat for 95 Plant Species From the Islands of Kauai and Niihau, HI; Final Rule VerDate Jan<31>2003 13:12 Feb 26, 2003 Jkt 200001 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 4717 Sfmt 4717 E:\FR\FM\27FER2.SGM 27FER2 9116 Federal Register / Vol. 68, No. 39 / Thursday, February 27, 2003 / Rules and Regulations DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR units designated for the 83 species. This FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Paul critical habitat designation requires the Henson, Field Supervisor, Pacific Fish and Wildlife Service Service to consult under section 7 of the Islands Office at the above address Act with regard to actions carried out, (telephone 808/541–3441; facsimile 50 CFR Part 17 funded, or authorized by a Federal 808/541–3470). agency. Section 4 of the Act requires us SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION: RIN 1018–AG71 to consider economic and other relevant impacts when specifying any particular Background Endangered and Threatened Wildlife area as critical habitat. This rule also and Plants; Final Designation or In the Lists of Endangered and determines that designating critical Nondesignation of Critical Habitat for Threatened Plants (50 CFR 17.12), there habitat would not be prudent for seven 95 Plant Species From the Islands of are 95 plant species that, at the time of species. We solicited data and Kauai and Niihau, HI listing, were reported from the islands comments from the public on all aspects of Kauai and/or Niihau (Table 1). -

Recovery Plan for Tyoj5llllt . I-Bland Plants

Recovery Plan for tYOJ5llllt. i-bland Plants RECOVERY PLAN FOR MULTI-ISLAND PLANTS Published by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon Approved: Date: / / As the Nation’s principal conservation agency, the Department of the Interior has responsibility for most ofour nationally owned public lands and natural resources. This includes fostering the wisest use ofour land and water resources, protecting our fish and wildlife, preserving the environmental and cultural values ofour national parks and historical places, and providing for the enjoyment of life through outdoor recreation. The Department assesses our energy and mineral resources and works to assure that their development is in the best interests ofall our people. The Department also has a major responsibility for American Indian reservation communities and for people who live in island Territories under U.S. administration. DISCLAIMER PAGE Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, sometimes prepared with the assistance ofrecovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Costs indicated for task implementation and/or time for achievement ofrecovery are only estimates and are subject to change. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval ofany individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, otherthan the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position ofthe U.S. -

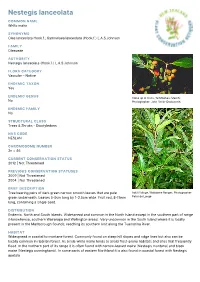

Nestegis Lanceolata

Nestegis lanceolata COMMON NAME White maire SYNONYMS Olea lanceolata Hook.f.; Gymnelaea lanceolata (Hook.f.) L.A.S.Johnson FAMILY Oleaceae AUTHORITY Nestegis lanceolata (Hook.f.) L.A.S.Johnson FLORA CATEGORY Vascular – Native ENDEMIC TAXON Yes ENDEMIC GENUS Close up of fruits, Te Moehau (March). No Photographer: John Smith-Dodsworth ENDEMIC FAMILY No STRUCTURAL CLASS Trees & Shrubs - Dicotyledons NVS CODE NESLAN CHROMOSOME NUMBER 2n = 46 CURRENT CONSERVATION STATUS 2012 | Not Threatened PREVIOUS CONSERVATION STATUSES 2009 | Not Threatened 2004 | Not Threatened BRIEF DESCRIPTION Tree bearing pairs of dark green narrow smooth leaves that are pale Adult foliage, Waitakere Ranges. Photographer: green underneath. Leaves 5-9cm long by 1-2.5cm wide. Fruit red, 8-11mm Peter de Lange long, containing a single seed. DISTRIBUTION Endemic. North and South Islands. Widespread and common in the North Island except in the southern part of range (Horowhenua, southern Wairarapa and Wellington areas). Very uncommon in the South Island where it is locally present in the Marlborough Sounds, reaching its southern limit along the Tuamarina River. HABITAT Widespread in coastal to montane forest. Commonly found on steep hill slopes and ridge lines but also can be locally common in riparian forest. As a rule white maire tends to avoid frost-prone habitats and sites that frequently flood. In the northern part of its range it is often found with narrow-leaved maire (Nestegis montana) and black maire (Nestegis cunninghamii). In some parts of eastern Northland it is also found in coastal forest with Nestegis apetala. FEATURES Stout gynodioecious spreading tree up to 20 m tall usually forming a domed canopy; trunk up to c. -

A Landscape-Based Assessment of Climate Change Vulnerability for All Native Hawaiian Plants

Technical Report HCSU-044 A LANDscape-bASED ASSESSMENT OF CLIMatE CHANGE VULNEraBILITY FOR ALL NatIVE HAWAIIAN PLANts Lucas Fortini1,2, Jonathan Price3, James Jacobi2, Adam Vorsino4, Jeff Burgett1,4, Kevin Brinck5, Fred Amidon4, Steve Miller4, Sam `Ohukani`ohi`a Gon III6, Gregory Koob7, and Eben Paxton2 1 Pacific Islands Climate Change Cooperative, Honolulu, HI 96813 2 U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, Hawaii National Park, HI 96718 3 Department of Geography & Environmental Studies, University of Hawai‘i at Hilo, Hilo, HI 96720 4 U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service —Ecological Services, Division of Climate Change and Strategic Habitat Management, Honolulu, HI 96850 5 Hawai‘i Cooperative Studies Unit, Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, Hawai‘i National Park, HI 96718 6 The Nature Conservancy, Hawai‘i Chapter, Honolulu, HI 96817 7 USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Hawaii/Pacific Islands Area State Office, Honolulu, HI 96850 Hawai‘i Cooperative Studies Unit University of Hawai‘i at Hilo 200 W. Kawili St. Hilo, HI 96720 (808) 933-0706 November 2013 This product was prepared under Cooperative Agreement CAG09AC00070 for the Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center of the U.S. Geological Survey. Technical Report HCSU-044 A LANDSCAPE-BASED ASSESSMENT OF CLIMATE CHANGE VULNERABILITY FOR ALL NATIVE HAWAIIAN PLANTS LUCAS FORTINI1,2, JONATHAN PRICE3, JAMES JACOBI2, ADAM VORSINO4, JEFF BURGETT1,4, KEVIN BRINCK5, FRED AMIDON4, STEVE MILLER4, SAM ʽOHUKANIʽOHIʽA GON III 6, GREGORY KOOB7, AND EBEN PAXTON2 1 Pacific Islands Climate Change Cooperative, Honolulu, HI 96813 2 U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Island Ecosystems Research Center, Hawaiʽi National Park, HI 96718 3 Department of Geography & Environmental Studies, University of Hawaiʽi at Hilo, Hilo, HI 96720 4 U. -

List 01 Hawaiian Names 01 Plants

V\.{). 3 v BOTANICAL BULLETIN NO.2 JUNE. 1913 TERRITORY OF HAWAII BOARD OF AGRICULTURE AND FORESTRY List 01 Hawaiian Names 01 Plants BY JOSEPH F. ROCK Consulting Botanist, Board of Agriculture and Forestry HONOLULU: HAWAIIAN GAZETTE CO., LTD. 1913 ALPHABETICAL LIST OF HAWAIIAN NAMES OF PLANTS. The following list of Hawaiian plant-names has been compiled from various sources. Hillebrand in his valuable Flora of the Hawaiian Islands has given many Hawaiian names, especially of the more common species; these are incorporated in this list with a few corrections. Nearly all Hawaiian plant-names found in this list and not in Hillebrand's Flora were secured from Mr. Francis Gay of the Island of Kauai, an old resident in this Terri tory and well acquainted with its plants from a layman's stand point. It was the writer's privilege to camp with Mr. Gay in the mountains of Kauai collecting botanical material; for almost every species he could give the native name, which he had se cured in the early days from old and reliable natives. Mr. Gay had made spatter prints of many of the native plants in a large record book with their names and uses, as well as their symbolic meaning when occurring in mele (songs) or olioli (chants), at tached to them. For all this information the writer is indebted mainly to Mr. Francis Gay and also to Mr. Augustus F. Knudsen of the same Island. The writer also secured Hawaiian names from old na tives and Kahunas (priests) in the various islands of the group. -

Game Management Plans to Facilitate Effective Program Implementation

Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources Division of Forestry and Wildlife Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Program Game Management Program FY17-FY21 Program Narrative W-22-G, Segments 17-21 1 Table of Contents Hawaii Game Management Program ................................................................................................. 4 Budget Schedule ................................................................................................................................. 7 Job Descriptions ................................................................................................................................. 8 Project 1.W-22-GC-1 State of Hawaii Game Program Planning and Coordination .......................... 8 Project 2.W-23-GL-1 Statewide Game Land Access and Acquisition……………………………..10 Project 3.W-29-GR-1 Game Mammal Research: Accurately Estimate Sheep and Goat Survival Rates, Population Demographics and Habitat Use in the Puu Waawaa Forest Reserve and Puu Anahulu GMA: West Hawaii……………………………………………………………...12 Project 4.W-30-NP Nāpuʻu Conservation Project Hawaii Island..…………………………………13 Project 5.W-24-GO-01 Game Operations and Maintenance: Hawaii County - East Hawaii District .......................................................................................................................................................... 14 Project 6.W-24-GO-02 Game Operations and Maintenance Hawaii County - West Hawaii District ......................................................................................................................................................... -

Bobea Sandwicensis (Gray) Hillebr

Common Forest Trees of Hawaii (Native and Introduced) ‘Ahakea wearability. Modern canoes are often painted yellow at the gunwales to simulate ‘ahakea wood. Also used for Bobea sandwicensis (Gray) Hillebr. poi boards and paddles. Scattered in wet to dry forests and on open lava flows Madder or coffee family (Rubiaceae) at 300–4000 ft (105–1220 m) elevation. Native species (endemic) Range Maui, Lanai, Molokai, and Oahu The genus Bobea, common name ‘ahakea, is known only from the Hawaiian Islands and has 4 or fewer species of Botanical synonym trees distributed through the islands. They have small Bobea hookeri Hillebr. paired pale green leaves with paired small pointed stipules that shed early, 1–7 small flowers at leaf bases, This genus was named in 1830 for M. Bobe-Moreau, with tubular greenish corolla, the four lobes overlap- physician and pharmacist in the French Marine. Three ping in bud, and small round black or purplish fruit other species are found on the large islands of Hawaii. (drupe), mostly dry, with 2–6 nutlets. This species, de- scribed below, will serve as an example. Medium-sized evergreen tree to 33 ft (10 m) high and 1 ft (0.3 m) in trunk diameter. Bark gray, smoothish, slightly warty, fissured, and scaly. Inner bark light brown, bitter. Twig light brown, with tiny pressed hairs and with rings at nodes. Leaves opposite, with pinkish finely hairy leafstalks 3 5 of ⁄8– ⁄8 inch (1 –1. 5 cm) and paired small pointed hairy 1 stipules ⁄8 inch (3 mm) long that form bud and shed 1 early. -

Guidance Document Pohakuloa Training Area Plant Guide

GUIDANCE DOCUMENT Recovery of Native Plant Communities and Ecological Processes Following Removal of Non-native, Invasive Ungulates from Pacific Island Forests Pohakuloa Training Area Plant Guide SERDP Project RC-2433 JULY 2018 Creighton Litton Rebecca Cole University of Hawaii at Manoa Distribution Statement A Page Intentionally Left Blank This report was prepared under contract to the Department of Defense Strategic Environmental Research and Development Program (SERDP). The publication of this report does not indicate endorsement by the Department of Defense, nor should the contents be construed as reflecting the official policy or position of the Department of Defense. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the Department of Defense. Page Intentionally Left Blank 47 Page Intentionally Left Blank 1. Ferns & Fern Allies Order: Polypodiales Family: Aspleniaceae (Spleenworts) Asplenium peruvianum var. insulare – fragile fern (Endangered) Delicate ENDEMIC plants usually growing in cracks or caves; largest pinnae usually <6mm long, tips blunt, uniform in shape, shallowly lobed, 2-5 lobes on acroscopic side. Fewer than 5 sori per pinna. Fronds with distal stipes, proximal rachises ocassionally proliferous . d b a Asplenium trichomanes subsp. densum – ‘oāli’i; maidenhair spleenwort Plants small, commonly growing in full sunlight. Rhizomes short, erect, retaining many dark brown, shiny old stipe bases.. Stipes wiry, dark brown – black, up to 10cm, shiny, glabrous, adaxial surface flat, with 2 greenish ridges on either side. Pinnae 15-45 pairs, almost sessile, alternate, ovate to round, basal pinnae smaller and more widely spaced.