Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

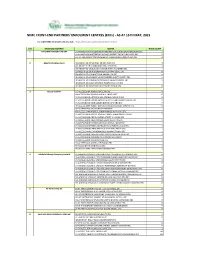

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (Ercs) - AS at 15TH MAY, 2021

NIMC FRONT-END PARTNERS' ENROLMENT CENTRES (ERCs) - AS AT 15TH MAY, 2021 For other NIMC enrolment centres, visit: https://nimc.gov.ng/nimc-enrolment-centres/ S/N FRONTEND PARTNER CENTER NODE COUNT 1 AA & MM MASTER FLAG ENT LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGBABIAKA STR ILOGBO EREMI BADAGRY ERC 1 LA-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG AGUMO MARKET OKOAFO BADAGRY ERC 0 OG-AA AND MM MATSERFLAG BAALE COMPOUND KOFEDOTI LGA ERC 0 2 Abuchi Ed.Ogbuju & Co AB-ABUCHI-ED ST MICHAEL RD ABA ABIA ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED BUILDING MATERIAL OGIDI ERC 2 AN-ABUCHI-ED OGBUJU ZIK AVENUE AWKA ANAMBRA ERC 1 EB-ABUCHI-ED ENUGU BABAKALIKI EXP WAY ISIEKE ERC 0 EN-ABUCHI-ED UDUMA TOWN ANINRI LGA ERC 0 IM-ABUCHI-ED MBAKWE SQUARE ISIOKPO IDEATO NORTH ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AFOR OBOHIA RD AHIAZU MBAISE ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UGBA AMAIFEKE TOWN ORLU LGA ERC 1 IM-ABUCHI-ED UMUNEKE NGOR NGOR OKPALA ERC 0 3 Access Bank Plc DT-ACCESS BANK WARRI SAPELE RD ERC 0 EN-ACCESS BANK GARDEN AVENUE ENUGU ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA WUSE II ERC 0 FC-ACCESS BANK LADOKE AKINTOLA BOULEVARD GARKI II ABUJA ERC 1 FC-ACCESS BANK MOHAMMED BUHARI WAY CBD ERC 0 IM-ACCESS BANK WAAST AVENUE IKENEGBU LAYOUT OWERRI ERC 0 KD-ACCESS BANK KACHIA RD KADUNA ERC 1 KN-ACCESS BANK MURTALA MOHAMMED WAY KANO ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ACCESS TOWERS PRINCE ALABA ONIRU STR ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADEOLA ODEKU STREET VI LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ADETOKUNBO ADEMOLA STR VI ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK IKOTUN JUNCTION IKOTUN LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK ITIRE LAWANSON RD SURULERE LAGOS ERC 1 LA-ACCESS BANK LAGOS ABEOKUTA EXP WAY AGEGE ERC 1 LA-ACCESS -

The Cholera Risk Assessment in Kano State, Nigeria: a Historical Review, Mapping of Hotspots and Evaluation of Contextual Factors

PLOS NEGLECTED TROPICAL DISEASES RESEARCH ARTICLE The cholera risk assessment in Kano State, Nigeria: A historical review, mapping of hotspots and evaluation of contextual factors 1 2 2 2 Moise Chi NgwaID *, Chikwe Ihekweazu , Tochi OkworID , Sebastian Yennan , 2 3 4 5 Nanpring Williams , Kelly ElimianID , Nura Yahaya Karaye , Imam Wada BelloID , David A. Sack1 1 Department of International Health, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland, United States of America, 2 Nigeria Centre for Disease Control, Abuja, Nigeria, 3 Department of a1111111111 Microbiology, University of Benin, Nigeria, 4 Department of Public Health and Disease Control, Kano State a1111111111 Ministry of Health, Kano, Nigeria, 5 Department of Public Health and Disease Control, Ministry of Health a1111111111 Kano, Kano, Nigeria a1111111111 a1111111111 * [email protected] Abstract OPEN ACCESS Nigeria is endemic for cholera since 1970, and Kano State report outbreaks annually with Citation: Ngwa MC, Ihekweazu C, Okwor T, Yennan high case fatality ratios ranging from 4.98%/2010 to 5.10%/2018 over the last decade. How- S, Williams N, Elimian K, et al. (2021) The cholera ever, interventions focused on cholera prevention and control have been hampered by a risk assessment in Kano State, Nigeria: A historical lack of understanding of hotspot Local Government Areas (LGAs) that trigger and sustain review, mapping of hotspots and evaluation of contextual factors. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 15(1): yearly outbreaks. The goal of this study was to identify and categorize cholera hotspots in e0009046. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal. Kano State to inform a national plan for disease control and elimination in the State. -

Nigeria Centre for Disease Control Protecting the Health of Nigerians

Nigeria Centre for Disease Control Protecting the health of Nigerians Cholera hotspots mapping in Nigeria Iliya Cheshi - NCDC [email protected] Profile: Nigeria • Nigeria is a federal republic comprising 36 states and the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja • Inhabited by more than 250 ethnic groups with over 500 distinct languages • Nigeria is divided roughly in half between Christians and Muslims 195.9 million (2018) Census 2 NIGERIA CENTRE FOR DISEASE CONTROL Introduction • Cholera remains a global public health problem, disproportionately affecting the tropical and sub-tropical areas of the world, where focal areas or hotspots play a key role in perpetuating the disease transmission • Targeting these hotspots with proven interventions e.g. Water, Sanitation and Hygiene (WaSH), as well as Oral Cholera Vaccines (OCV) could reduce the mean annual incidence of the entire sub-Saharan African region by half (Lessler et al) • The Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC) has thus advocated for a comprehensive cholera control strategy where the use of OCV plays a complementary role to other preventive interventions, chiefly, ensuring access to WaSH 3 NIGERIA CENTRE FOR DISEASE CONTROL • To align its cholera control strategies with the global road map of the GTFCC, the team at the Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) released a document detailing their preparedness and response plans • Assessing cholera transmission dynamics in Nigeria and identifying cholera hotspots were outlined as immediate-term goals. This help to design and implement relevant long term and cost effective solutions to achieve the ultimate goal of cholera elimination 4 NIGERIA CENTRE FOR DISEASE CONTROL Cholera hotspot mapping in Nigeria “Cholera hotspot” is defined as a geographically limited area (e.g. -

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: the Role of Traditional Institutions

Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Edited by Abdalla Uba Adamu ii Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria Past, Present, and Future Proceedings of the National Conference on Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria. Organized by the Kano State Emirate Council to commemorate the 40th anniversary of His Royal Highness, the Emir of Kano, Alhaji Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD, as the Emir of Kano (October 1963-October 2003) H.R.H. Alhaji (Dr.) Ado Bayero, CFR, LLD 40th Anniversary (1383-1424 A.H., 1963-2003) Allah Ya Kara Jan Zamanin Sarki, Amin. iii Copyright Pages © ISBN © All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the editors. iv Contents A Brief Biography of the Emir of Kano..............................................................vi Editorial Note........................................................................................................i Preface...................................................................................................................i Opening Lead Papers Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: The Role of Traditional Institutions...........1 Lt. General Aliyu Mohammed (rtd), GCON Chieftaincy and Security in Nigeria: A Case Study of Sarkin Kano Alhaji Ado Bayero and the Kano Emirate Council...............................................................14 Dr. Ibrahim Tahir, M.A. (Cantab) PhD (Cantab) -

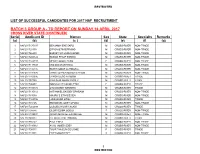

Batch 3 Group A

RESTRICTED LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES FOR 2017 NAF RECRUITMENT BATCH 3 GROUP A - TO REPORT ON SUNDAY 16 APRIL 2017 CROSS RIVER STATE (CONTINUED) Serial Applicant ID Names Sex State Specialty Remarks (a) (b) (c ) (d) (e) (f) (g) 1 NAF2017175197 BENJAMIN ENE EKPO M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 2 NAF201728378 EFFIOM ETIM EFFIONG M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 3 NAF201746430 BASSEY SYLVANUS OKON M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 4 NAF2017200122 EDIKAN PHILIP ESSIEN M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 5 NAF2017148737 MERCY OKON EKPO F CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 6 NAF2017117347 ENE EDEM ANTIGHA M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 7 NAF2017186435 EDWIN IOBAR ACHIBONG M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 8 NAF2017191076 CHRISTOPHER MOSES EFFIOM M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 9 NAF2017166695 UKPONG ESO AKABOM M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 10 NAF201767788 PAULINUS OKON BASSEY M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 11 NAF201796402 IMMACULATA OKON ETIM F CROSS-RIVER TRADE 12 NAF2017100172 OTU BASSEY KENNETH M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 13 NAF2017135112 NATHANIEL BASSEY EPHRAIM M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 14 NAF201733038 MAURICE ETIM ESSIEN M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 15 NAF2017169796 LUKE OGAR OTAH M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 16 NAF201745165 EMMANUEL ODEY OFUNA M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 17 NAF2017202699 OGBUDU HILARY AGABI M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 18 NAF201798686 GLORY ELIMA ODIDO F CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 19 NAF2017199991 ADADA MICHAEL EKANNAZE M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 20 NAF201749812 CLEMENT ADIE BISONG M CROSS-RIVER TRADE 21 NAF201786142 PAUL ENEJI . M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 22 NAF2017180661 ACHU JAMES ODEY M CROSS-RIVER NON-TRADE 23 NAF201706031 TOURITHA EUNICE USHIE F CROSS-RIVER -

Transcript of Hajiya Binta Abdulhamid Interviewer: Elisha Renne

GLOBAL FEMINISMS COMPARATIVE CASE STUDIES OF WOMEN’S ACTIVISM AND SCHOLARSHIP SITE: NIGERIA Transcript of Hajiya Binta Abdulhamid Interviewer: Elisha Renne Location: Kano, Nigeria Date: 31st January, 2020 University of Michigan Institute for Research on Women and Gender 1136 Lane Hall Ann Arbor, MI 48109-1290 Tel: (734) 764-9537 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.umich.edu/~glblfem © Regents of the University of Michigan, 2017 Hajiya Binta Abdulhamid was born on March 20, 1965, in Kano, the capital of Kano State, in northern Nigeria. She attended primary school and girls’ secondary school in Kano and Kaduna State. Thereafter she attended classes at Bayero University in Kano, where she received a degree in Islamic Studies. While she initially wanted to be a journalist, in 1983 she was encouraged to take education courses at the tertiary level in order to serve as a principal in girls’ secondary schools in Kano State. While other women had served in this position, there has been no women from Kano State who had done so. She has subsequently worked under the Kano State Ministry of Education, serving as school principal in several girls’ secondary schools in Kano State. Her experiences as a principal and teacher in these schools has enabled her to support girl child education in the state and she has encouraged women students to complete their secondary school education and to continue on to postgraduate education. She sees herself as a woman-activist in her advocacy of women’s education and has been gratified to see many of her former students working as medical doctors, lawyers, and politicians. -

A Publication of the Department of Religious and Cultural Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Port Harcourt P.M.B 5323 Choba, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

JOURNAL OF RELIGION AND CULTURE VOLUME 20, NO 2, 2020 A PUBLICATION OF THE DEPARTMENT OF RELIGIOUS AND CULTURAL STUDIES, FACULTY OF HUMANITIES, UNIVERSITY OF PORT HARCOURT P.M.B 5323 CHOBA, PORT HARCOURT, NIGERIA UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN LIBRARY i JOURNAL OF RELIGION AND CULTURE VOLUME 20, NUMBER TWO, 2020 EDITORIAL BOARD EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Prof. K. I. Owete ASSISTANT EDITORS Dr. C. Mbonu (Executive Editor) Dr. J. O. Obineche (Reviews Editor) Dr. J. N. Gbule (Research Editor) Dr. J. U. Odili (Secretary) Dr. I. Suberu (Assistant Secretary) EDITORIAL CONSULTANTS Prof. W. O. Wotogbe-Weneka (University of Port Harcourt) Prof. A. O. Folorunsho (Lagos State University) Prof. C. I. Ejizu (University of Port Harcourt) Prof. F. M. Mbon (University of Calabar) Prof. A. R. O. Kilani (University of Port Harcourt) Prof. S. I. Udoidem (University of Port Harcourt) Prof. M. A. Bidmus (University of Lagos) Prof. M. Opeloye (Obafemi Awolowo University) Prof. Vincent Nyoyoko (Akwa Ibom State University) Prof. I. O. Oloyede (University of Ilorin) UNIVERSITY OF IBADAN LIBRARY ii ENQUIRIES All enquiries and subscription should be directed to the Secretary Dr. O.U. Jones and Dr. I. Suberu, Department of Religious and Cultural Studies, Faculty of Humanities, University of Port Harcourt, P.M.B. 5323, Port Harcourt, Rivers State, Nigeria, email: [email protected] or visit our website www.joracuniport.com or telephone 07038133706, 08032219105. Interested scholars may submit the Manuscript of well-researched works at any time of the year for possible publication in duplicate (15-20 A4 pages) with a CD-ROM in Microsoft Word format, 12 points, Time New Roman. -

PROVISIONAL LIST.Pdf

S/N NAME YEAR OF CALL BRANCH PHONE NO EMAIL 1 JONATHAN FELIX ABA 2 SYLVESTER C. IFEAKOR ABA 3 NSIKAK UTANG IJIOMA ABA 4 ORAKWE OBIANUJU IFEYINWA ABA 5 OGUNJI CHIDOZIE KINGSLEY ABA 6 UCHENNA V. OBODOCHUKWU ABA 7 KEVIN CHUKWUDI NWUFO, SAN ABA 8 NWOGU IFIONU TAGBO ABA 9 ANIAWONWA NJIDEKA LINDA ABA 10 UKOH NDUDIM ISAAC ABA 11 EKENE RICHIE IREMEKA ABA 12 HIPPOLITUS U. UDENSI ABA 13 ABIGAIL C. AGBAI ABA 14 UKPAI OKORIE UKAIRO ABA 15 ONYINYECHI GIFT OGBODO ABA 16 EZINMA UKPAI UKAIRO ABA 17 GRACE UZOME UKEJE ABA 18 AJUGA JOHN ONWUKWE ABA 19 ONUCHUKWU CHARLES NSOBUNDU ABA 20 IREM ENYINNAYA OKERE ABA 21 ONYEKACHI OKWUOSA MUKOSOLU ABA 22 CHINYERE C. UMEOJIAKA ABA 23 OBIORA AKINWUMI OBIANWU, SAN ABA 24 NWAUGO VICTOR CHIMA ABA 25 NWABUIKWU K. MGBEMENA ABA 26 KANU FRANCIS ONYEBUCHI ABA 27 MARK ISRAEL CHIJIOKE ABA 28 EMEKA E. AGWULONU ABA 29 TREASURE E. N. UDO ABA 30 JULIET N. UDECHUKWU ABA 31 AWA CHUKWU IKECHUKWU ABA 32 CHIMUANYA V. OKWANDU ABA 33 CHIBUEZE OWUALAH ABA 34 AMANZE LINUS ALOMA ABA 35 CHINONSO ONONUJU ABA 36 MABEL OGONNAYA EZE ABA 37 BOB CHIEDOZIE OGU ABA 38 DANDY CHIMAOBI NWOKONNA ABA 39 JOHN IFEANYICHUKWU KALU ABA 40 UGOCHUKWU UKIWE ABA 41 FELIX EGBULE AGBARIRI, SAN ABA 42 OMENIHU CHINWEUBA ABA 43 IGNATIUS O. NWOKO ABA 44 ICHIE MATTHEW EKEOMA ABA 45 ICHIE CORDELIA CHINWENDU ABA 46 NNAMDI G. NWABEKE ABA 47 NNAOCHIE ADAOBI ANANSO ABA 48 OGOJIAKU RUFUS UMUNNA ABA 49 EPHRAIM CHINEDU DURU ABA 50 UGONWANYI S. AHAIWE ABA 51 EMMANUEL E. -

Admitted 02 05 2021

UNIVERSITY OF MAIDUGURI (Office of the Registrar) UTME ADMISSION 2020/2021 SESSION COLLEGE OF MEDICAL SCIENCES FACULTY OF BASIC MEDICAL SCIENCES MEDICINE AND SURGERY S/No REG No. NAME SEX COURSE 1 22183327EF ALIYU ADAMU MUSTAPHA M MBBS 2 21869820IA ISHAKU JEREMIAH NAGA M MBBS 3 22308067CA BUKAR ABDULHAKIM ALHAJI M MBBS 4 21972433BF FADAIRO IFEOLUWA MOSES M MBBS 5 20334581IF HABUTALIB SAIDU M MBBS 6 21907127DA AYUBA IBRAHIM HAMMAN M MBBS 7 22264216BF JAMES JACOB M MBBS 8 22173432CF LAWAN ABUBAKAR BANJABA M MBBS 9 21818672IA MUSA SULEIMAN ABDULLAHI M MBBS 10 20712900DF ANAMJA ALPHA GADZAMA M MBBS 11 20275771BF ABWA LAWRENCE TERVER M MBBS 12 20351415IF DANIEL ELIJAH M MBBS 13 21169457AF EZE FORTUNE CHUKWUMA M MBBS 14 22158006BF TERYILA HILARY AONDONA M MBBS 15 20819736EA MUHAMMAD AISHA GUDUF F MBBS 16 20334435FF SANUSI MONTARI BATO M MBBS 17 20336492DA EKE KENNETH ANTHONY M MBBS 18 20343071AF MOMOH JOSHUA D M MBBS 19 20334925HF USMAN ABDULSALAM MUHAMMAD M MBBS 20 22183342GF IBRAHIM HARUNA BABALE M MBBS 21 21754608GA ISMAIL AISHAT OJOBALARO F MBBS 22 22165363JA JOHN JETHRO JELLA M MBBS 23 21996113IA MUHAMMAD SANI M MBBS 24 20648452DF NNAJI CYPRAIN CHIEMERIE M MBBS 1 25 20350933CF AKILU HABIB KINGING M MBBS 26 20306188CF AKINNUSOYE OLAYINKA VICTOR M MBBS 27 21763279CF BILYAMINU ABUBAKAR M MBBS 28 21863022GA OLATUNDE YINKA DOTUN M MBBS 29 22173452CA IBRAHIM MUHAMMAD MUHAMMAD M MBBS 30 20333441IF MUHAMMAD YAKUBU AMUDA M MBBS 31 20990274HA ABUBAKAR DANIEL BADE M MBBS 32 22260227BA GREAT OKWUMA M MBBS 33 21337249IF OLUWADIYA MERCY INIOLUWA F MBBS -

In Changing Nigerian Society: a Discussion from the Perspective of Ibn Khaldun’S Concept Ofñumran

THE CONTRIBUTION OF UTHMAN BIN FODUYE (D.1817) IN CHANGING NIGERIAN SOCIETY: A DISCUSSION FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF IBN KHALDUN’S CONCEPT OFÑUMRAN SHUAIBU UMAR GOKARUMalaya of ACADEMY OF ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR University 2017 THE CONTRIBUTION OF UTHMAN BIN FODUYE (D.1817) IN CHANGING NIGERIAN SOCIETY: A DISCUSSION FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF IBN KHALDUN’S CONCEPT OF ÑUMRAN SHUAIBU UMAR GOKARU Malaya THESIS SUBMITTED IN FULFILMENTof OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UniversityACADEMY OF ISLAMIC STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA KUALA LUMPUR 2017 UNIVERSITY OF MALAYA ORIGINAL LITERARY WORK DECLARATION Name of Candidate: Shuaibu Umar Gokaru Matric No: IHA140056 Name of Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title of Project Paper/Research Report/Dissertation/Thesis (“this Work”) THE CONTRIBUTION OF UTHMAN BIN FODUYE (D. 1817) IN CHANGING NIGERIAN SOCIETY: A DISCUSSION FROM THE PERSPECTIVE OF IBN KHALDUN’S CONCEPT OF ÑUMRAN Field of Study: Islamic Civilisation (Religion) I do solemnly and sincerely declare that: (1) I am the sole author/author of this Work; (2) This Work is original; (3) Any use of any work in which copyright exists was done by way of fair dealing and for permitted purposes and any excerpt or extract from, or reference to or reproduction of any copyrightMalaya work has been disclosed expressly and sufficiently and the title of the Work and its authorship have been acknowledged in this Work; (4) I do not have any actual knowledge nor do I ought reasonably to know that the making of this work -

Kingdom of Kano

Kingdom of Kano Country Nigeria Kingdom Kano The Kingdom of Kano was a Hausa kingdom in the north of what is now Nigeria that dates back before 1000 AD, and lasted until the Fulani jihad in 1805. The kingdom was then replaced by the Kano Emirate, subject to the Sokoto Caliphate. The capital is now the modern city of Kano in Kano State.[1] Contents [hide] 1 Location 2 Early history 3 Rumfa dynasty 4 See also 5 References Location Kano lies to the north of the Jos Plateau, located in the Sudanian Savanna region that stretches across the south of the Sahel. The city lies near where the Kano and Challawa rivers flowing from the southwest converge to form the Hadejia River, which eventually flows into Lake Chad to the east. The climate is hot all year round. Rainfall is variable, ranging from 350mm to 1,300mm annually with the mean around 950mm, almost all falling during June–September period. Traditionally agriculture was based on lifting water to irrigate small parcels of land along river channels in the dry season, known as the Shadouf system. At the time when the kingdom was flourishing, tree cover would have been more extensive and the soil less degraded than it is today.[2] Early history Our knowledge of the early history of Kano comes largely from the Kano Chronicle, a compilation of oral tradition and some older documents composed in the nineteenth century, as well as more recently conducted archaeology. In the 7th century, Dala Hill, a hill in Kano, was the site of a community that engaged in iron- working. -

Historical Origin and Customary Land Tenancy of Rural Community in Nigeria

専修大学社会科学研究所 月報 No.684 2020 年 6 月 Historical origin and customary land tenancy of rural community in Nigeria Regina Hoi Yee Fu Introduction This paper is a record of the historical origin and customary land tenancy of the agricultural villages in Nigeria, West Africa. The ethnic group of the people concerned are the Nupe, which is the most dominant ethnic group in Niger State of Nigeria. The research was conducted in the area locates on the so-called “Middle Belt” which stretches across central Nigeria longitudinally between the eighth and the twelfth parallels north. The Middle Belt is populated largely by minority ethnic groups and is characterized by a heterogeneity and diversity of peoples and cultures. In the Niger State, the other major ethnic groups apart from the Nupe are the Hausa, the Gwari, the Fulani and the Kumuka. Literature concerning the rural Nupe community are very rare (Nadel, 1942, 1954; Forde, 1955; Masuda, 2002). The contents of this paper are mainly based on the information gathered by direct observation and unstructured interviews with local people during interrupted fieldwork conducted between 2004 and 2009. This paper aims to fill the information gap about the rural society in Nigeria, as information about the society of this country has been limited due to prolonged political instability since the 1980s. Research Area The area in which I conducted fieldwork for this paper is the “Cis-Kaduna” region of the Bida Emirate of the Niger State. Niger State locates on the central-north geopolitical zone of Nigeria1. The drainage of the state is dominated by the Niger River which forms its southern boundary.