Cardinal Numbers: Changing Patterns of Malaria and Mortality in Rome

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reception of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Work in Italy

Chapter 24 The Reception of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Work in Italy Fabrizio De Falco The reception of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s work in medieval Italy is an integral part of two fascinating veins of inquiry: the early appearance of the Matter of Britain in Italy and its evolution in various social, political, and cultural con- texts around the Peninsula.1 At the beginning of the 12th century, before the De gestis Britonum was written, an unedited Arthurian legend was carved on Modena Cathedral’s Portale della Pescheria, a stop for pilgrims headed to Rome along the Via Francigena.2 Remaining in the vicinity of Modena, the only con- tinental witness of the First Variant Version of the DGB (Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, 982) can be connected to Nonantola Abbey.3 Moving to the kingdom of Sicily, in 1165 the archbishop of Otranto commissioned an enormous mosaic for the cathedral, and Arthur is depicted in one of the various scenes, astride a goat, fighting a large cat.4 To describe Geoffrey of Monmouth’s reception in 1 E.G. Gardener, The Arthurian Legend in Italian Literature, London and New York, 1930; D. Delcorno Branca, “Le storie arturiane in Italia”, in P. Boitani, M. Malatesta, and A. Vàrvaro (eds.), Lo spazio letterario del Medioevo, II. Il Medioevo volgare, III: La ricezione del testo, Rome, 2003, pp. 385–403; G. Allaire and G. Paski (eds.), The Arthur of the Italians: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Italian Literature and Culture (Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, 7), Cardiff, 2014. 2 In this version, Gawain is the protagonist and Arthur is not yet king. -

" a Great and Lasting Beginning": Bishop John Mcmullen's

22 Catholic Education/June 2005 ARTICLES “A GREAT AND LASTING BEGINNING”: BISHOP JOHN MCMULLEN’S EDUCATIONAL VISION AND THE FOUNDING OF ST. AMBROSE UNIVERSITY GEORGE W. MCDANIEL St. Ambrose University Catholic education surfaces as a focus and concern in every age of the U.S. Catholic experience. This article examines the struggles in one, small Midwestern diocese surrounding the establishment and advancement of Catholic education. Personal rivalries, relationship with Rome, local politics, finances, responding to broader social challenges, and the leadership of cler- gy were prominent themes then, as they are now. Numerous historical insights detailed here help to explain the abiding liberal character of Catholicism in the Midwestern United States. n the spring of 1882, Bishop John McMullen, who had been in the new IDiocese of Davenport for about 6 months, met with Father Henry Cosgrove, the pastor of St. Marguerite’s (later Sacred Heart) Cathedral. “Where shall we find a place to give a beginning to a college?” McMullen asked. Cosgrove’s response was immediate: “Bishop, I will give you two rooms in my school building.” “All right,” McMullen said, “let us start at once” (The Davenport Democrat, 1904; Farrell, 1982, p. iii; McGovern, 1888, p. 256; Schmidt, 1981, p. 111). McMullen’s desire to found a university was not as impetuous as it may have seemed. Like many American Catholic leaders in the 19th century, McMullen viewed education as a way for a growing immigrant Catholic population to advance in their new country. Catholic education would also serve as a bulwark against the encroachment of Protestant ideas that formed the foundation of public education in the United States. -

Uses of the Past in Twelfth-Century Germany: the Case of the Middle High German Kaiserchronik Mark Chinca and Christopher Young

Uses of the Past in Twelfth-Century Germany: The Case of the Middle High German Kaiserchronik Mark Chinca and Christopher Young Abstract: Despite its broad transmission and its influence on vernacular chronicle writing in the German Middle Ages, the Kaiserchronik has not received the attention from historians that it deserves. This article describes some of the ideological, historical, and literary contexts that shaped the original composition of the chronicle in the middle of the twelfth century: Christian salvation history, the revival of interest in the Roman past, the consolidation of a vernacular literature of knowledge, and the emergence of a practice of writing history as “serious entertainment” by authors such as Geoffrey of Monmouth and Godfrey of Viterbo. Placed in these multiple contexts, which have a European as well as a specifically German dimension, the Kaiserchronik emerges as an important document of the uses of the past in fostering a sense of German identity among secular and ecclesiastical elites in the high Middle Ages. The Kaiserchronik, completed probably in Regensburg ca.1150, is a seminal work.1 Monumental in scale, it comprises over seventeen thousand lines of Middle High German verse and is the first verse chronicle in any European language. Through a grand narrative of the reigns of thirty-six Roman and nineteen German emperors filling a timespan of twelve centuries, it throws the spotlight on ethnicity, religion and cultural identity, and on the relationship between church and empire, as these issues play out on the various stages of Rome, Germany and their territorial outposts in the Mediterranean basin.2 The Kaiserchronik has several claims to uniqueness. -

Ten Years of Winter: the Cold Decade and Environmental

TEN YEARS OF WINTER: THE COLD DECADE AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSCIOUSNESS IN THE EARLY 19 TH CENTURY by MICHAEL SEAN MUNGER A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of History and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy June 2017 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Michael Sean Munger Title: Ten Years of Winter: The Cold Decade and Environmental Consciousness in the Early 19 th Century This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of History by: Matthew Dennis Chair Lindsay Braun Core Member Marsha Weisiger Core Member Mark Carey Institutional Representative and Scott L. Pratt Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded June 2017 ii © 2017 Michael Sean Munger iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Michael Sean Munger Doctor of Philosophy Department of History June 2017 Title: Ten Years of Winter: The Cold Decade and Environmental Consciousness in the Early 19 th Century Two volcanic eruptions in 1809 and 1815 shrouded the earth in sulfur dioxide and triggered a series of weather and climate anomalies manifesting themselves between 1810 and 1819, a period that scientists have termed the “Cold Decade.” People who lived during the Cold Decade appreciated its anomalies through direct experience, and they employed a number of cognitive and analytical tools to try to construct the environmental worlds in which they lived. Environmental consciousness in the early 19 th century commonly operated on two interrelated layers. -

Peripheral Packwater Or Innovative Upland? Patterns of Franciscan Patronage in Renaissance Perugia, C.1390 - 1527

RADAR Research Archive and Digital Asset Repository Peripheral backwater or innovative upland?: patterns of Franciscan patronage in renaissance Perugia, c. 1390 - 1527 Beverley N. Lyle (2008) https://radar.brookes.ac.uk/radar/items/e2e5200e-c292-437d-a5d9-86d8ca901ae7/1/ Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder(s). The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. When referring to this work, the full bibliographic details must be given as follows: Lyle, B N (2008) Peripheral backwater or innovative upland?: patterns of Franciscan patronage in renaissance Perugia, c. 1390 - 1527 PhD, Oxford Brookes University WWW.BROOKES.AC.UK/GO/RADAR Peripheral packwater or innovative upland? Patterns of Franciscan Patronage in Renaissance Perugia, c.1390 - 1527 Beverley Nicola Lyle Oxford Brookes University This work is submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirelnents of Oxford Brookes University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. September 2008 1 CONTENTS Abstract 3 Acknowledgements 5 Preface 6 Chapter I: Introduction 8 Chapter 2: The Dominance of Foreign Artists (1390-c.1460) 40 Chapter 3: The Emergence of the Local School (c.1450-c.1480) 88 Chapter 4: The Supremacy of Local Painters (c.1475-c.1500) 144 Chapter 5: The Perugino Effect (1500-c.1527) 197 Chapter 6: Conclusion 245 Bibliography 256 Appendix I: i) List of Illustrations 275 ii) Illustrations 278 Appendix 2: Transcribed Documents 353 2 Abstract In 1400, Perugia had little home-grown artistic talent and relied upon foreign painters to provide its major altarpieces. -

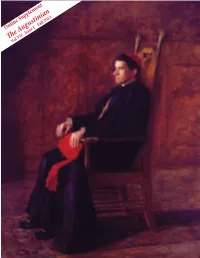

The Augustinian Vol VII

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St. -

The Reception of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Work in Italy

Chapter 24 The Reception of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Work in Italy Fabrizio De Falco The reception of Geoffrey of Monmouth’s work in medieval Italy is an integral part of two fascinating veins of inquiry: the early appearance of the Matter of Britain in Italy and its evolution in various social, political, and cultural con- texts around the Peninsula.1 At the beginning of the 12th century, before the De gestis Britonum was written, an unedited Arthurian legend was carved on Modena Cathedral’s Portale della Pescheria, a stop for pilgrims headed to Rome along the Via Francigena.2 Remaining in the vicinity of Modena, the only con- tinental witness of the First Variant Version of the DGB (Paris, Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal, 982) can be connected to Nonantola Abbey.3 Moving to the kingdom of Sicily, in 1165 the archbishop of Otranto commissioned an enormous mosaic for the cathedral, and Arthur is depicted in one of the various scenes, astride a goat, fighting a large cat.4 To describe Geoffrey of Monmouth’s reception in 1 E.G. Gardener, The Arthurian Legend in Italian Literature, London and New York, 1930; D. Delcorno Branca, “Le storie arturiane in Italia”, in P. Boitani, M. Malatesta, and A. Vàrvaro (eds.), Lo spazio letterario del Medioevo, II. Il Medioevo volgare, III: La ricezione del testo, Rome, 2003, pp. 385–403; G. Allaire and G. Paski (eds.), The Arthur of the Italians: The Arthurian Legend in Medieval Italian Literature and Culture (Arthurian Literature in the Middle Ages, 7), Cardiff, 2014. 2 In this version, Gawain is the protagonist and Arthur is not yet king. -

Greenfield, P. N. 2011. Virgin Territory

_____________________________________ VIRGIN TERRITORY THE VESTALS AND THE TRANSITION FROM REPUBLIC TO PRINCIPATE _____________________________________ PETA NICOLE GREENFIELD 2011 Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Classics and Ancient History The University of Sydney ABSTRACT _____________________________________ The cult of Vesta was vital to the city of Rome. The goddess was associated with the City’s very foundation, and Romans believed that the continuity of the state depended on the sexual and moral purity of her priestesses. In this dissertation, Virgin Territory: The Vestals and the Transition from Republic to Principate, I examine the Vestal cult between c. 150 BCE and 14 CE, that is, from the beginning of Roman domination in the Mediterranean to the establishment of authoritarian rule at Rome. Six aspects of the cult are discussed: the Vestals’ relationship with water in ritual and literature; a re-evaluation of Vestal incestum (unchastity) which seeks a nuanced approach to the evidence and examines the record of incestum cases; the Vestals’ extra-ritual activities; the Vestals’ role as custodians of politically sensitive documents; the Vestals’ legal standing relative to other Roman women, especially in the context of Augustus’ moral reform legislation; and the cult’s changing relationship with the topography of Rome in light of the construction of a new shrine to Vesta on the Palatine after Augustus became pontifex maximus in 12 BCE. It will be shown that the cult of Vesta did not survive the turmoil of the Late Republic unchanged, nor did it maintain its ancient prerogative in the face of Augustus’ ascendancy. -

Section-175-G-H.Pdf

IPI name number Rights holder 52846 GIANFRANCO GABBANI 5390510 NATALE CARUSO 13809303 TIZIANO CANTATORE 14725404 FABIO FERRIANI 16633794 SALVATORE PUMO 16671294 RAFFAELE RENNA 16722992 GIANNI ROVERSI 17101044 GIUSEPPE ZAMMITTI 26363594 ROSARIO RODILOSSO 37309391 LUCIO FABBRI 37313206 LUIGI FINIZIO 37404300 RICCARDO SPRECACENERE 38662367 MARCO FALAGIANI 38818555 FABRIZIO FRAIOLI 38984130 ANDREA BIANCHINI 41150826 ANTONIO NARDONE 42711215 FLORINDO CIMEI 42867175 ALESSANDRO MARUSSO 42897261 MARCO ZANINI 42953774 GIANFRANCO LUGANO 44990657 IVANO BORGAZZI 45014517 GENNARO FIORILLO 46146197 DANIELE SAVELLI 46247581 GIANNI SALAORNI 46305301 ROBERTO RUGGERI 47356961 FULVIO MUZIO 47398155 CLAUDIO GIOVANNINI 47437569 GIANNI TONELLO 47507282 ALBERTO GIACALONE 47519272 LUCA MORI 47526571 ROBERTO RIVA 47531876 BRUNO STELLA 47555268 NICOLA LAISO 47573952 ANGELO OLIVA 47578055 ROBERTO AITA 47632084 GIUSEPPE FARACE 50391897 CLAUDIO CASTELLANI 50469684 VINCENZO LIBERTI 51620218 FABRIZIO ALESSANDRINI 51645786 FULVIO GUIDARELLI 51649382 ROBERTO ROSSI 51706990 GENNARO IPPOLITO 51713208 MARIO CAMILLETTI 51785079 ARTURO GIACOMO OLIVIERI 51805694 MAURIZIO CASOLI 51818093 STEFANO IATOSTI 52237305 MILOS STANKOVIC 57920660 PELLEGRINO DAVID 57972144 MAURO LICONTE 58064279 ENRICO RUGGERI 58094561 MAURIZIO SECONDI 59558828 GUIDO POLITI 59565833 MAURIZIO FABRIZIO 59565931 SALVATORE FABRIZIO 71958156 GIANCARLO DI ROCCO 82428866 JAMES RITCHIE 84751554 GIANNA ALBINI 84757830 TOMMASO ARICO' 84845737 MATTEO BONSANTO 84952933 WALTER COLOMBO 84964923 PASQUALE DAVIDE 84974331 -

Sant Agostino

(078/31) Sant’Agostino in Campo Marzio Sant'Agostino is an important 15th century minor basilica and parish church in the rione Sant'Eustachio, not far from Piazza Navona. It is one of the first Roman churches built during the Renaissance. The official title of the church is Sant'Agostino in Campo Marzio. The church and parish remain in the care of the Augustinian Friars. The dedication is to St Augustine of Hippo. [2] History: The convent of Sant’Agostino attached to the church was founded in 1286, when the Roman nobleman Egidio Lufredi donated some houses in the area to the Augustinian Friars (who used to be called "Hermits of St Augustine" or OESA). They were commissioned by him to erect a convent and church of their order on the site and, after gaining the consent of Pope Honorius IV, this was started. [2] Orders to build the new church came in 1296, from Pope Boniface VIII. Bishop Gerard of Sabina placed the foundation stone. Construction was to last nearly one and a half century. It was not completed until 1446, when it finally became possible to celebrate liturgical functions in it. [2] However, a proposed church for the new convent had to wait because of its proximity to the small ancient parish church of San Trifone in Posterula, dedicated to St Tryphon and located in the Via della Scrofa. It was a titular church, and also a Lenten station. In 1424 the relics of St Monica, the mother of St Augustine, were brought from Ostia and enshrined here as well. -

L'arte Diplomatica Del Pontificato Di Pio II

Alcuni esempi dell’arte diplomatica del pontificato di Pio II Rita Boarelli Ho un ricordo ancora vivo dell’emozione vissuta nel 2009, quando ebbi il piacere di visitare per la prima volta l’Archivio storico diocesano di Matelica. Tra i tanti documenti conservati al suo interno e sopravvis- suti a saccheggi e ad un tremendo incendio nel 1710, trovai due pergamene risalenti al pontificato di papa Pio II. Erano due bolle esecutorie che in molti conside- ravano perse e che riguardava la storia della nobile fa- miglia Maccafani, che a Matelica giunse nel XVIII se- colo, fondendosi poi con la famiglia Buglioni che qui viveva da tempo. Leggendo, colsi l’occasione per ap- profondire la complessa figura di Enea Silvio Piccolo- mini ed in special modo soffermando la mia attenzione verso un'attività, quella dell'abile diplomatico, che gli permise di tracciare un solco di rinascita durante il suo pur breve pontificato, che non fu certo esente dal “ne- potismo” sebbene costantemente rivolto a sostenere i migliori elementi che, di volta in volta, ebbe a disposi- zione, cercando in tutte le occasioni di “costruire” la “pace” e la “concordia”. Va detto che Pio II dovette af- frontare un’età non certo facile politicamente e social- mente, trovandosi a regnare su uno Stato esistente più sulla carta che nei fatti, con principi e despoti sempre in guerra tra loro o alleati contro di lui. In più, in un si- stema che a livello europeo stava vivendo una profon- 49 da trasformazione, dovendo fronteggiare e contenere i diritti nobiliari accampati su aree talvolta anche extra terminos. -

St. Barnabas and the Modern History of the Cypriot Archbishop's Regalia Privileges

Messiah University Mosaic History Educator Scholarship History 2015 The Donation of Zeno: St. Barnabas and the Modern History of the Cypriot Archbishop'S Regalia Privileges Joseph P. Huffman Messiah University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/hist_ed Part of the History Commons Permanent URL: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/hist_ed/12 Recommended Citation Huffman, Joseph P., "The Donation of Zeno: St. Barnabas and the Modern History of the Cypriot Archbishop'S Regalia Privileges" (2015). History Educator Scholarship. 12. https://mosaic.messiah.edu/hist_ed/12 Sharpening Intellect | Deepening Christian Faith | Inspiring Action Messiah University is a Christian university of the liberal and applied arts and sciences. Our mission is to educate men and women toward maturity of intellect, character and Christian faith in preparation for lives of service, leadership and reconciliation in church and society. www.Messiah.edu One University Ave. | Mechanicsburg PA 17055 The Donation of Zeno: St Barnabas and the Origins of the Cypriot Archbishops' Regalia Privileges by JOSEPH P. HUFFMAN This article explores medieval and Renaissance evidence for the origins and rneaning of the imperial regalia privileges exercised by the Greek archbishops of Cyprus, said to have been granted by the Ernperor Zeno ( c. 42 to 9- I), along with autocephaly, upon the discovery of the relics of the Apostle Barnabas. Though clairned to have existed ab antiquo, these imperial privileges in fact have their origin in the late sixteenth century and bear the characteristics of western Latin ecclesial and political thought. With the Donation of Constantine as their pmtotype, they bolster the case rnade to the Italians and the French for saving Christian Cyprus frorn the Turks.