Ten Years of Winter: the Cold Decade and Environmental

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mathematics Is a Gentleman's Art: Analysis and Synthesis in American College Geometry Teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2000 Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 Amy K. Ackerberg-Hastings Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Higher Education and Teaching Commons, History of Science, Technology, and Medicine Commons, and the Science and Mathematics Education Commons Recommended Citation Ackerberg-Hastings, Amy K., "Mathematics is a gentleman's art: Analysis and synthesis in American college geometry teaching, 1790-1840 " (2000). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 12669. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/12669 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margwis, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. in the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. -

Climbing the Sea Annual Report

WWW.MOUNTAINEERS.ORG MARCH/APRIL 2015 • VOLUME 109 • NO. 2 MountaineerEXPLORE • LEARN • CONSERVE Annual Report 2014 PAGE 3 Climbing the Sea sailing PAGE 23 tableofcontents Mar/Apr 2015 » Volume 109 » Number 2 The Mountaineers enriches lives and communities by helping people explore, conserve, learn about and enjoy the lands and waters of the Pacific Northwest and beyond. Features 3 Breakthrough The Mountaineers Annual Report 2014 23 Climbing the Sea a sailing experience 28 Sea Kayaking 23 a sport for everyone 30 National Trails Day celebrating the trails we love Columns 22 SUMMIT Savvy Guess that peak 29 MEMbER HIGHLIGHT Masako Nair 32 Nature’S WAy Western Bluebirds 34 RETRO REWIND Fred Beckey 36 PEAK FITNESS 30 Back-to-Backs Discover The Mountaineers Mountaineer magazine would like to thank The Mountaineers If you are thinking of joining — or have joined and aren’t sure where Foundation for its financial assistance. The Foundation operates to start — why not set a date to Meet The Mountaineers? Check the as a separate organization from The Mountaineers, which has received about one-third of the Foundation’s gifts to various Branching Out section of the magazine for times and locations of nonprofit organizations. informational meetings at each of our seven branches. Mountaineer uses: CLEAR on the cover: Lori Stamper learning to sail. Sailing story on page 23. photographer: Alan Vogt AREA 2 the mountaineer magazine mar/apr 2015 THE MOUNTAINEERS ANNUAL REPORT 2014 FROM THE BOARD PRESIDENT Without individuals who appreciate the natural world and actively champion its preservation, we wouldn’t have the nearly 110 million acres of wilderness areas that we enjoy today. -

Granville Brian Chetwynd-Staplyton

Granville Brian Chetwynd-Staplyton How can I make you acquainted, I wonder? Above middle height, [5’8”] straight and square, fair hair, blue eyes, small fair moustache, a handsome face with a grave expression and altogether of an aristocratic appearance, and no wonder, for this family trace their descent from before the Conquest. He is rather quiet to outsiders but I don't find him so. I think we are something alike in some things, for instance most people think us both very reserved, excepting those who know us best. [Elizabeth Chetwynd- Stapylton to her sister March 1, 1886] It stretches one’s mind to believe that the mastermind behind the development of an English Colony near the western border of present Lake County, Florida in early 1882, was an ambitious, energetic 23 year-old English entrepreneur and a pioneer of dogged determination, Granville Brian Chetwynd-Stapylton. Granville Brian Chetwynd-Stapylton Stapylton, the youngest of four children, was born December 11, 1858, to William and Elizabeth Briscoe Tritton Chetwynd-Stapylton. His father was then the vicar of Old Malden Church, also known as St. John the Baptist Church, Surrey, London, England. Given the surname it should come as no surprise that this family is found in Burke's Peerage, Barontage and Knightage , a major royal, aristocratic and historical reference book. Granville descends from Sir Robert Constable, Knight of Flamborough (1423-1480). Although his father was an Oxford graduate Granville chose Haileybury College where, as an honor student, his interests were drama and geology. He is enumerated as a commercial clerk to a colonial broker in London in the 1881 English census along with his father, his sister Ella, a brother Frederick, a cook, a parlourmaid, a housemaid and a coachman. -

Alexander Hill Everett, Ou L'artisan Américain D'une Identité Cubaine

Alexander Hill Everett, ou l’artisan américain d’une identité cubaine. (Axe IV, Symposium 16) Rahma Jerad To cite this version: Rahma Jerad. Alexander Hill Everett, ou l’artisan américain d’une identité cubaine. (Axe IV, Sympo- sium 16). Independencias - Dependencias - Interdependencias, VI Congreso CEISAL 2010, Jun 2010, Toulouse, France. halshs-00502328 HAL Id: halshs-00502328 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00502328 Submitted on 20 Jul 2010 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Rahma Jerad Université Paris I – Panthéon Sorbonne/ LARCA CEISAL « Dépendances, Indépendances, Interdépendances » Alexander Hill Everett, ou l'artisan américain d'une identité cubaine Résumé: A partir du dix-huitième siècle, pour des raisons idéologiques, stratégiques et économiques, l'île de Cuba était dans la ligne de mire de la jeune république américaine, dont les dirigeants et la population rêvaient d'étendre le territoire sur le continent et au-delà. Les Etats-Unis ont usé nombre de stratagèmes pour devenir les heureux propriétaires de ce splendide joyau, des propositions d'achat aux pressions diplomatiques pour en éloigner les grandes puissances européennes en passant par les campagnes de propagande dans la presse. -

(1826-1846) / Salvador García

Salvador García Castañeda Presencia de Washington Irving y otros norteamericanos en la España Romántica (1826-1846) Boletín de la Biblioteca de Menéndez Pelayo. LXXXVII, 2011, 113-126 PRESENCIA DE WASHINGTON IRVING Y OTROS NORTEAMERICANOS EN LA ESPAÑA ROMÁNTICA (1826-1846)* ashington Irving es el representante más destacado, y el más conocido entre nos- otros, de la atracción que ejerció España sobre un considerable grupo de norte- Wamericanos quienes a lo largo del siglo XIX dejaron profunda huella de sus experiencias en la cultura de su país. Una huella manifiesta en libros de viajes, en traba- jos históricos y literarios, en la creación de bibliotecas y de colecciones de obras de arte, en el extraordinario auge de los estudios universitarios de la lengua, la cultura y la litera- tura españolas en los Estados Unidos y, finalmente, en difundir el conocimiento de España en aquel país. Esta conferencia tiene el carácter de una visión de conjunto pues me pro- pongo referirme a temas tan amplios como el magisterio y huella de Washington Irving y otros hispanófilos norteamericanos de la primera mitad del XIX sobre la literatura de su país en el momento de transición de la Ilustración al Romanticismo, así como a su deci- siva influencia sobre la difusión de los estudios universitarios del español en los Estados Unidos. Me he marcado tentativamente las fechas de 1826 a 1846 por ser respectivamente la de la primera visita a España del Washington Irving autor de Los cuentos de la Alham- bra, y la de la última como representante diplomático de su país. En aquellos años la vida cultural, política y económica norteamericana estaba con- centrada principalmente en Nueva Inglaterra, al Este del país, y principalmente en Fila- delfia, que fue la primera capital de los Estados Unidos, en Boston y en Nueva York. -

" a Great and Lasting Beginning": Bishop John Mcmullen's

22 Catholic Education/June 2005 ARTICLES “A GREAT AND LASTING BEGINNING”: BISHOP JOHN MCMULLEN’S EDUCATIONAL VISION AND THE FOUNDING OF ST. AMBROSE UNIVERSITY GEORGE W. MCDANIEL St. Ambrose University Catholic education surfaces as a focus and concern in every age of the U.S. Catholic experience. This article examines the struggles in one, small Midwestern diocese surrounding the establishment and advancement of Catholic education. Personal rivalries, relationship with Rome, local politics, finances, responding to broader social challenges, and the leadership of cler- gy were prominent themes then, as they are now. Numerous historical insights detailed here help to explain the abiding liberal character of Catholicism in the Midwestern United States. n the spring of 1882, Bishop John McMullen, who had been in the new IDiocese of Davenport for about 6 months, met with Father Henry Cosgrove, the pastor of St. Marguerite’s (later Sacred Heart) Cathedral. “Where shall we find a place to give a beginning to a college?” McMullen asked. Cosgrove’s response was immediate: “Bishop, I will give you two rooms in my school building.” “All right,” McMullen said, “let us start at once” (The Davenport Democrat, 1904; Farrell, 1982, p. iii; McGovern, 1888, p. 256; Schmidt, 1981, p. 111). McMullen’s desire to found a university was not as impetuous as it may have seemed. Like many American Catholic leaders in the 19th century, McMullen viewed education as a way for a growing immigrant Catholic population to advance in their new country. Catholic education would also serve as a bulwark against the encroachment of Protestant ideas that formed the foundation of public education in the United States. -

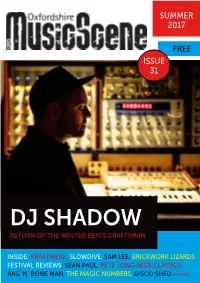

Dj Shadow Return of the Master Beats Craftsman

SUMMER 2017 FREE ISSUE 31 DJ SHADOW RETURN OF THE MASTER BEATS CRAFTSMAN INSIDE: KRAFTWERK, SLOWDIVE, SAM LEE, BRICKWORK LIZARDS FESTIVAL REVIEWS: SEAN PAUL, PETE TONG IBIZA CLASSICS, RAG ‘N’ BONE MAN, THE MAGIC NUMBERS, DISCO SHED & MORE OMS31 MUSIC NEWS There’s a history of multi – venue metro festivals in Cowley Road with Truck’s OX4 and then Gathering setting the pace. Well now Future Perfect have taken up the baton with Ritual Union on Saturday October 21. Venues are the O2 Academy 1 and 2, The Library, The Bullingdon and Truck Store. The first stage of acts announced includes Peace, Toy, Pinkshinyultrablast, Flamingods, Low Island, Dead Reborn local heroes Ride are sounding in fine stage Pretties, Her’s, August List and Candy Says with DJ fettle judging by their appearance at the 6 Music sets from the Drowned in Sound team. Tickets are Festival in Glasgow. The former Creation shoegaze £25 in advance. trailblazers play the New Theatre, Oxford on July 10, having already appeared at Glastonbury, their The Jericho Tavern in Walton Street have a new first local show in many years. They have also promoter to run their upstairs gigs. Heavy Pop announced a major UK tour. The eagerly awaited are well – known in Reading having run the Are new album, the Erol Alkan produced Weather Diaries You Listening? festival there for 5 years. Already is just released. (See our album review in the Local confirmed are an appearance from Tom Williams Releases section). Tickets for New Theatre gig with (formerly of The Boat) on September 16 and Original Spectres supporting, can be bought from Rabbit Foot Spasm Band on October 13 with atgtickets.com Peerless Pirates and Other Dramas. -

WINTER 1998 TH In*Vi'i§

a i 9dardy'fernSFoundationm Editor Sue Olsen VOLUME 7 NUMBER 1 WINTER 1998 TH in*vi'i§ Presidents’ Message: More Inside... Jocelyn Horder and Anne Holt, Co-Presidents Polypodium polypodioides.2 Greetings and best wishes for a wonderful fern filled 1998. At this winter time of year Deer Problems.2 many of our hardy ferns offer a welcome evergreen touch to the garden. The varied textures are particularly welcome in bare areas. Meanwhile ferns make wonderful Book Review.3 companions to your early spring flowering bulbs and blooming plants. Since we are Exploring Private having (so far) a mild winter continue to control the slugs and snails that are lurking European Gardens Continued.4 around your ferns and other delicacies. Mr. Gassner Writes.5 Don’t forget to come to the Northwest Flower and Garden show February 4-8 to enjoy Notes from the Editor.5 the colors, fragrances and fun of spring. The Hardy Fern Foundation will have a dis¬ play of ferns in connection with the Rhododendron Species Botanical Garden. Look for Fem Gardens of the Past and a Garden in Progress.6-7 booth #6117-9 on the fourth floor of the Convention Center where we will have a dis¬ play of ferns, list of fern sources, cultural information and as always persons ready to Fem Finding in the Hocking Hills.8-10 answer your questions. Anyone interested in becoming more involved with the Hardy Blechnum Penna-Marina Fern Foundation will have a chance to sign up for volunteering in the future. Little Hard Fem.10 We are happy to welcome the Coastal Botanical Garden in Maine as a new satellite The 1997 HFF garden. -

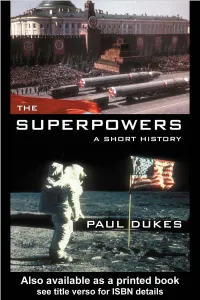

The Superpowers: a Short History

The Superpowers The Superpowers: a short history is a highly original and important book surveying the development of the USA and Russia (in its tsarist, Soviet and post-Soviet phases) from the pre-twentieth century world of imperial powers to the present. It places the Cold War, from inception to ending, into the wider cultural, economic and political context. The Superpowers: a short history traces the intertwining history of the two powers chronologically. In a fascinating and innovative approach, the book adopts the metaphor of a lifespan to explore this evolutionary relationship. Commencing with the inheritance of the two countries up to 1898, the book continues by looking at their conception to 1921, including the effects of the First World War, gestation to 1945 with their period as allies during the Second World War and their youth examining the onset of the Cold War to 1968. The maturity phase explores the Cold War in the context of the Third World to 1991 and finally the book concludes by discussing the legacy the superpowers have left for the twenty- first century. The Superpowers: a short history is the first history of the two major participants of the Cold War and their relationship throughout the twentieth century and before. Paul Dukes is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Aberdeen. His many books include A History of Russia (Macmillan, 3rd edition, 1997) and World Order in History (Routledge, 1996). To Daniel and Ruth The Superpowers A short history Paul Dukes London and New York First published 2001 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE Simultaneously published in the USA and Canada by Routledge 29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2002. -

“Little Tibet” with “Little Mecca”: Religion, Ethnicity and Social Change on the Sino-Tibetan Borderland (China)

“LITTLE TIBET” WITH “LITTLE MECCA”: RELIGION, ETHNICITY AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE SINO-TIBETAN BORDERLAND (CHINA) A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Yinong Zhang August 2009 © 2009 Yinong Zhang “LITTLE TIBET” WITH “LITTLE MECCA”: RELIGION, ETHNICITY AND SOCIAL CHANGE ON THE SINO-TIBETAN BORDERLAND (CHINA) Yinong Zhang, Ph. D. Cornell University 2009 This dissertation examines the complexity of religious and ethnic diversity in the context of contemporary China. Based on my two years of ethnographic fieldwork in Taktsang Lhamo (Ch: Langmusi) of southern Gansu province, I investigate the ethnic and religious revival since the Chinese political relaxation in the 1980s in two local communities: one is the salient Tibetan Buddhist revival represented by the rebuilding of the local monastery, the revitalization of religious and folk ceremonies, and the rising attention from the tourists; the other is the almost invisible Islamic revival among the Chinese Muslims (Hui) who have inhabited in this Tibetan land for centuries. Distinctive when compared to their Tibetan counterpart, the most noticeable phenomenon in the local Hui revival is a revitalization of Hui entrepreneurship, which is represented by the dominant Hui restaurants, shops, hotels, and bus lines. As I show in my dissertation both the Tibetan monastic ceremonies and Hui entrepreneurship are the intrinsic part of local ethnoreligious revival. Moreover these seemingly unrelated phenomena are in fact closely related and reflect the modern Chinese nation-building as well as the influences from an increasingly globalized and government directed Chinese market. -

Quality &Flavor

PROVENANCE THE TRUE AUSSIE BEEF & LAMB STORY 3 menu-ready opportunities Culinary ideation & support Unsurpassed quality &flavor A TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Why Australia? 2 2. The Aussie way 4 3. Aussie lamb 12 4. Aussie beef 18 5. Aussie goat 26 6. Three menu-ready opportunities 30 7. Always the star 38 8. The mindful movement 42 9. Aussie support 44 10. Guide to cuts of Aussie beef, lamb and goat 46 Produced by Meat & Livestock Australia - North America Suite 550, 1100 Vermont Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20005 Answering today’s 1. WHY demands Today, it’s pretty obvious that most Apart from the important narrative around consumers care about where their sourcing, you need to be able to serve up AUSTRALIA? food comes from. They care about today’s menu trends in new and delightful animal husbandry and sustainability. ways. Aussie beef and lamb are delicious, so We care, too. It’s the Aussie way, that’s good, for a start. They also shine in coded into the DNA of our ranchers many of today’s biggest trends—from next- and farmers, and carried all the way level tacos to modern bowl builds. We’re Life on the land from paddock to plate. ready to help with creative approaches that deliver craveable results. By serving Aussie beef and lamb, you’re Australia is a special place. It’s got more than 200 years building that important emotional under its belt producing high quality beef and lamb. We’re connection with your guests, letting them know you care about sourcing and proud of that legacy and we’re proud of our product, raised sustainability. -

Mark Howard Long Instructor University of Central Florida 100 Weldon Blvd., PC #3013 Sanford, FL 32773 407.708.2816 ______

Mark Howard Long Instructor University of Central Florida 100 Weldon Blvd., PC #3013 Sanford, FL 32773 407.708.2816 ____________________________________________________________ AFFILIATION Instructor, University of Central Florida, History Department. PROFESSIONAL FEILDS U. S. History: American South, Frontier/Borderlands, Maritime, Labor, Florida. EDUCATION 2007 Ph. D. Loyola University, Chicago. History 2005 M.A. Loyola University, Chicago. History 1984 B.A., Auburn University. Political Science. RESEARCH AND PUBLICATION Book Chapters: “„A Decidedly Mutinous Spirit‟: The „Labor Problem‟ in the Postbellum South as an Exercise of Free Labor; a Case Study of Sanford, Florida;” in Florida’s Labor and Working Class Past: Three Centuries of Work in the Sunshine State, eds. Melanie Shell-Weiss and Robert Cassanello, The University Press of Florida, 2008. Reviews: "Tampa Bay History Center." Journal of American History (June 2010). “History for the Twenty First Century: The 114th Annual Meeting of the American Historical Association.” International Labor and Working Class History No. 58, Fall 2000. Encyclopedia Entries: “Gurnee, IL,” entry for the Encyclopedia of Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2004. Conference Papers: "'Another Kind of Slavery': Maritime Mobility and Unfree Labor in a New South Context," Southern Historical Association, October 2011 (forthcoming). "Banana Republic or Margaritaville?: Jimmy Buffett's Greater Caribbean as a Libidinal Space," Sea Music Symposium, Mystic Seaport, June 2011. "Surfing Florida: A Public History," National Council of Public History, April 2011. "Reconstruction/Re-creation/Recreation: Remaking Florida's Postbellum Frontier," Western Historical Association, October 2010. "A Cautionary Tale: Monocrop Agriculture and Development in Florida in the Postbellum Period," Agricultural History Society, June 2010. "Creating the Sunshine State: Maritime Tourism in Florida in the Nineteenth Century," Maritime in the Humanities, October 2009.