Peripheral Packwater Or Innovative Upland? Patterns of Franciscan Patronage in Renaissance Perugia, C.1390 - 1527

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cbc Conservazione Beni Culturali

DIPINTI SU TAVOLA E MANUFATTI LIGNEI CBC CONSERVAZIONE BENI CULTURALI La Cooperativa CBC Conservazione Beni Culturali si è costituita nel 1977 tra restauratori provenienti dai corsi dell'Istituto Centrale del Restauro. E' attualmente formata da venti soci, il cui curriculum di studio è consultabile su questo sito. Opera sia per Enti pubblici (Soprintendenze regionali, Comuni, Musei Civici, etc.), che per privati, anche come strutture od Enti, sia in Italia che all’estero. Nel seguente curriculum si dà conto dettagliatamente dell'attività svolta nel settore specifico, suddivisa e ordinata per anno di esecuzione. Presso la sua sede laboratorio sono consultabili le documentazioni sia scritte che fotografiche dei lavori svolti, di cui è stata consegnata copia ai committenti; alcuni lavori sono inoltre stati oggetto di approfondimento e pubblicazione. Contatti Sede legale e laboratorio in Laboratorio in Via dei Priori, 84 Viale Manzoni, 26 - 00185 Roma 06123 Perugia Tel: 06-70.49.52.82 fax: 06-77.200.500 Tel: 075-57.31.532 Mail: [email protected] Mail: [email protected] Sito: www.cbccoop.it FB: @cbccoop Dati Amministrativi Codice Fiscale e numero d’iscrizione al Registro delle Imprese di Roma: N. 02681720583 P.IVA: N. 01101321006 – R.E.A. di Roma: N. 413625 del 12.03.1977 Albo Provinciale delle Imprese Artigiane: N. 133916 del 05.06.1980 Albo delle Società Cooperative al N. A125967 del 23.03.2005 Attestazione di qualificazione alla esecuzione dei lavori pubblici per la Categoria OS2A Classifica IV. DIPINTI SU TAVOLA E MANUFATTI LIGNEI In corso Teramo, Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta Jacobello del Fiore: Polittico raffigurante Incoronazione di Maria e Santi Segretariato Regionale per l’Abruzzo Fondazione Trivulzio Autori vari del sec. -

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520)

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520) The Artist as Universal Man and Individual Genius By Susan Behrends Frank, Ph.D. Associate Curator for Research The Phillips Collection What are the new ideas behind the Italian High Renaissance? • Commitment to monumental interpretation of form with the human figure at center stage • Integration of form and space; figures actually occupy space • New medium of oil allows for new concept of luminosity as light and shadow (chiaroscuro) in a manner that allows form to be constructed in space in a new way • Physiological aspect of man developed • Psychological aspect of man explored • Forms in action • Dynamic interrelationship of the parts to the whole • New conception of the artist as the universal man and individual genius who is creative in multiple disciplines Michelangelo The Artists of the Italian High Renaissance Considered Universal Men and Individual Geniuses Raphael- Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci- Self-Portrait Michelangelo- Pietà- 1498-1500 St. Peter’s, Rome Leonardo da Vinci- Mona Lisa (Lisa Gherardinidi Franceso del Giacondo) Raphael- Sistine Madonna- 1513 begun c. 1503 Gemäldegalerie, Dresden Louvre, Paris Leonardo’s Notebooks Sketches of Plants Sketches of Cats Leonardo’s Notebooks Bird’s Eye View of Chiana Valley, showing Arezzo, Cortona, Perugia, and Siena- c. 1502-1503 Storm Breaking Over a Valley- c. 1500 Sketch over the Arno Valley (Landscape with River/Paesaggio con fiume)- 1473 Leonardo’s Notebooks Studies of Water Drawing of a Man’s Head Deluge- c. 1511-12 Leonardo’s Notebooks Detail of Tank Sketches of Tanks and Chariots Leonardo’s Notebooks Flying Machine/Helicopter Miscellaneous studies of different gears and mechanisms Bat wing with proportions Leonardo’s Notebooks Vitruvian Man- c. -

Quellen Und Forschungen Aus Italienischen Archiven Und Bibliotheken Band 52 (1972) Herausgegeben Vom Deutschen Historischen Inst

Quellen und Forschungen aus italienischen Archiven und Bibliotheken Band 52 (1972) Herausgegeben vom Deutschen Historischen Institut Rom Copyright Das Digitalisat wird Ihnen von perspectivia.net, der Online-Publikationsplattform der Max Weber Stiftung – Deutsche Geisteswissenschaftliche Institute im Ausland, zur Verfügung gestellt. Bitte beachten Sie, dass das Digitalisat urheberrechtlich geschützt ist. Erlaubt ist aber das Lesen, das Ausdrucken des Textes, das Herunterladen, das Speichern der Daten auf einem eigenen Datenträger soweit die vorgenannten Handlungen ausschließlich zu privaten und nicht- kommerziellen Zwecken erfolgen. Eine darüber hinausgehende unerlaubte Verwendung, Reproduktion oder Weitergabe einzelner Inhalte oder Bilder können sowohl zivil- als auch strafrechtlich verfolgt werden. DIE MAILÄNDISCHE HERRSCHAFT IN PERUGIA (1400-1403)* von HERMANN M. GOLDBRUNNER Die juristische Grundlage, auf welcher die mailändische Herr schaft in Perugia beruhte, stellt der am 19. Januar 1400 im Prioren- palast von Perugia von der Generalversammlung der Zünfte einstim mig gebilligte und am darauffolgenden Tag von Stefano di Luca und *) Revidierte und mit Anmerkungen versehene deutsche Fassung des am 19. Mai 1969 auf dem Settimo Convegno di studi umbri in Gubbio gehaltenen Vortrages. Die italienische Fassung wird in den Atti del VII Convegno di studi umbri voraussichtlich 1973 erscheinen. - Für großzügiges Entgegenkommen und freundliche Hilfe danke ich dem Direktor des Staatsarchivs in Perugia, Herrn Prof. Dr. Roberto Abbondanza, herzlichst. Frau Dr. Liliana Piu vom Deutschen Historischen Institut in Rom versagte mir ihren Rat nie, wenn ich mich mit Fragen, welche die Edition italienischer Texte betrafen, an sie wandte. - Im folgenden werden Eigennamen, soweit sie in der Literatur geläufig sind, in italienischer Form wiedergegeben. In allen anderen Fällen belasse ich die latinisierte Schreibung absichtlich. -

Review of Shearman's Collection of Raphael Documents

BOOK REVIE'WS was inserted to make it more imrnediate, in 1936, in which most documents are not of the role previously played by Golzio) for all suggest that it was the fint scene to be published in full. monographic study, and can thereby assumea painted, and technical evidence prompts us to In the period since Shearman's book has canonical position which inhibits ftesh con- reconsider the sequence of the frescos inde- appeared the re-daring ofthe Monteluce doc- sideration of the evidence. pendendy oftheir preparation on paper. uments to r5o5, not r5o3 bp.sr-96),, and of In a moment of characteristic wit. Shear- If Raphael's contemporaries averred that Raphael's appointrnent as Sctiptor Breuium in man describes what a biography of Raphael his art was not innate but born from studying I5II, not r5og (pp.r5o-52),3have made pos- based entirely upon f).lsedocuments would 'Would be other artists, they were not totally wrong, par- sible new interpretations ofthe artist's career. like (p. r 5). he have been asamused by ticularly in regard to his early career. Raphael Sadly, however, Shearman's Corpus doesn't what a student's chronology of Raphael's life seemed to need models to emulate and sur- acfually tell us very much more about based on this publication might be like? There pass. His syncretic method, by which he Raphael than we knew already. There are would be much that was good and uncon- selected from al1 available models, painting new documents in this book (for instance, tentious, but Raphael would be said to have techniques, lighting, figure moti6, poses, those connected with Alberrinelli, supplied by been in Rome in rso2/o3; in r5o4 the only 'Signed landscape motifi, backdrops, accoutrements Louis Waldman), and it is extremely useful to entry would read and dated The Spos- and cosfumes may make him particularly have them gathered together in one place (if alizio in Citti di Castello (now Milan, Brera)',6 'gilded interesting in an age of multivalent informa- not in one volume), but we do not have the wh.ile in r5o8 Raphael would have a tron. -

Animal Life in Italian Painting

UC-NRLF III' m\ B 3 S7M 7bS THE LIBRARY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESENTED BY PROF. CHARLES A. KOFOID AND MRS. PRUDENCE W. KOFOID ANIMAL LIFE IN ITALIAN PAINTING THt VISION OF ST EUSTACE Naiionai. GaM-KUV ANIMAL LIFE IN ITALIAN PAINTING BY WILLIAM NORTON HOWE, M.A. LONDON GEORGE ALLEN & COMPANY, LTD. 44 & 45 RATHBONE PLACE 1912 [All rights reserved] Printed by Ballantvne, Hanson 6* Co. At the Ballantyne Press, Edinburgh / VX-/ e3/^ H67 To ©. H. PREFACE I OWE to Mr. Bernhard Berenson the suggestion which led me to make the notes which are the foundation of this book. In the chapter on the Rudiments of Connoisseurship in the second series of his Study and Criticism of Italian Art, after speaking of the characteristic features in the painting of human beings by which authorship " may be determined, he says : We turn to the animals that the painters, of the Renaissance habitually intro- duced into pictures, the horse, the ox, the ass, and more rarely birds. They need not long detain us, because in questions of detail all that we have found to apply to the human figure can easily be made to apply by the reader to the various animals. I must, however, remind him that animals were rarely petted and therefore rarely observed in the Renaissance. Vasari, for instance, gets into a fury of contempt when describing Sodoma's devotion to pet birds and horses." Having from my schooldays been accustomed to keep animals and birds, to sketch them and to look vii ANIMAL LIFE IN ITALIAN PAINTING for them in painting, I had a general recollection which would not quite square with the statement that they were rarely petted and therefore rarely observed in the Renaissance. -

The Last Supper Seen Six Ways by Louis Inturrisi the New York Times, March 23, 1997

1 Andrea del Castagno’s Last Supper, in a former convent refectory that is now a museum. The Last Supper Seen Six Ways By Louis Inturrisi The New York Times, March 23, 1997 When I was 9 years old, I painted the Last Supper. I did it on the dining room table at our home in Connecticut on Saturday afternoon while my mother ironed clothes and hummed along with the Texaco. Metropolitan Operative radio broadcast. It took me three months to paint the Last Supper, but when I finished and hung it on my mother's bedroom wall, she assured me .it looked just like Leonardo da Vinci's painting. It was supposed to. You can't go very wrong with a paint-by-numbers picture, and even though I didn't always stay within the lines and sometimes got the colors wrong, the experience left me with a profound respect for Leonardo's achievement and a lingering attachment to the genre. So last year, when the Florence Tourist Bureau published a list of frescoes of the Last Supper that are open to the public, I was immediately on their track. I had seen several of them, but never in sequence. During the Middle Ages the ultima cena—the final supper Christ shared with His disciples before His arrest and crucifixion—was part of any fresco cycle that told His life story. But in the 15th century the Last Supper began to appear independently, especially in the refectories, or dining halls, of the convents and monasteries of the religious orders founded during the Middle Ages. -

Virgin Enthroned, School of Jacopo Di Cione

The Technical and Historical Findings of an Investigation of a Fourteenth-Century Florentine Panel from the Courtauld Gallery Collection By Roxane Sperber and Anna Cooper The Conservation and Art Historical Analysis: Works from the Courtauld Gallery Project aimed to carry out technical investigation and art historical research on a gothic arched panel from the Courtauld Gallery Collection [P.1947.LF.202] (fig 1).1 The panel was undergoing conservation treatment and was thus well positioned for such investigation. The following report will outline the findings of this study. It will address the dating, physical construction, iconography, and attribution of the work, as well as the likely function of the work and the workshop decisions which contributed to its production. Dating Stylistic and iconographic characteristics indicate that this work originated in Florence and dates to the last decade of the fourteenth century. The panel is divided into two scenes; the lower scene depicts a Madonna of Humility, the Virgin seated on the ground surrounded by four standing saints, and the upper portion of the work is a Crucifixion with the Virgin and St John the Evangelist (the dolenti) seated at the cross. It is difficult to trace the precise origins of the Madonna of Humility and the Dolenti Seated at the Cross. There is no consensus as to the origins of these formats, although numerous proposals have been suggested.2 Millard Meiss proposed that the Madonna of Humility originated in Siena with a panel by Simone Martini,3 who also produced a fresco of the same subject in Avignon.4 Beth Williamson agrees that these mid fourteenth-century works were early examples of the Madonna of Humility, but suggests that the Avignon fresco came first and the panel, also produced during Martini’s time in France, was sent back to the Dominican convent in Siena, an institution to which Martini had ties.5 The Madonna of Humility gained popularity throughout the second half of the fourteenth century and into the fifteenth century. -

Perugia Through Words and Pictures

1 Journal logo Perugia through words and pictures Franco Ivan Nucciarelli Faculty of Humanities, University of Perugia, 06123 Perugia, Italy Elsevier use only: Received date here; revised date here; accepted date here Abstract Selected topics in the historical and the architectural legacy of Perugia and its University are reviewed in this introductory contribution to the 2010 edition of the BEACH series conferences, hosted in the Aula Magna of the University of Perugia. Keywords: Type your keywords here, separated by semicolons ; Perugia, University of Perugia, history, art, architecture; century. On the basis of this irreproachable documentary evidence, the 700th anniversary of the 1. Introduction foundation was celebrated two years ago. This hall•, which is much younger than the speaker, was solemnly inaugurated in 1959 in the presence of 2. Cultural heritage of the University of Perugia the President of the Republic, when the speaker was just a young high school student. Do not, however, Hosted at the beginning in the Bishop’s palace, the let the age of this hall fool you about the age of the University had its own premises donated by Pope University, which was founded in the middle of the Sixtus IV to the city around the 1470s; the thirteenth century and can claim to be one of construction was contemporaneous with the Sistine Europe’s oldest universities. The French cardinal Chapel. This fifteenth-century building, still called Bertrand de Got, when elected pope in a conclave in the Old University (Figs. 1 & 2), is currently Perugia, took the name of Clement V and transferred occupied by the Courthouses, but its return to the the capital of the Pontifical States from Rome to University is anticipated. -

This Raphael Is for Real

This Raphael is for real In the pinks: The National's Madonna. Photo: National Gallery, London For the next three months, Raphael's Madonna of the Pinks, acquired in March by the National Gallery for £22m, can be seen in our new exhibition Raphael: From Urbino to Rome, alongside 37 other paintings by the young artist. This provides an unequalled opportunity to examine the claims by Professor James Beck, reported in yesterday's Times, that this painting is not by Raphael. When a painting is as expensive as Madonna of the Pinks, it is to be expected that the gallery's decision to acquire it should be properly scrutinised. But the questions asked of the picture need to be the right ones. One person's opinion, however vociferously expressed, isn't sufficient reason to doubt a picture's authenticity. The story of the rediscovery of the painting is well known. Dr Nicholas Penny, then working at the National Gallery and the author of a major monograph on Raphael, noticed the picture on a visit to Alnwick in 1991. It had long been regarded as the best surviving copy of a lost composition by Raphael; no art historian believed it was by Raphael himself. But Penny thought it worth borrowing for examination in the gallery's scientific department. By the early 1990s, the National Gallery had recognised that a connoisseur's judgment needs to be backed up by science. Only by examining the way Raphael's painting was made could we abandon the idea that the picture was a copy. Penny found that a remarkable free drawing, very like many of Raphael's works on paper, lay under the paint. -

Stories on Umbria

RACCONTAMI L’UMBRIA STORIES ON UMBRIA CONCORSO GIORNALISTICO • FESTIVAL INTERNAZIONALE DEL GIORNALISMO EDIZIONE JOURNALISM AWARD • INTERNATIONAL JOURNALISM FESTIVAL 2015 • JOURNALISM AWARD • INTERNATIONAL JOURNALISM FESTIVAL • INTERNATIONAL AWARD • JOURNALISM 2015 STORIES ON UMBRIA STORIES • • CONCORSO GIORNALISTICO • FESTIVAL INTERNAZIONALE DEL GIORNALISMO • CONCORSO GIORNALISTICO FESTIVAL 2015 SELEZIONE DI SERVIZI A SELECTION OF NEWS GIORNALISTICI CHE HANNO TRATTATO STORIES ABOUT UMBRIA, LE ECCELLENZE ARTISTICHE, ITS ARTISTIC, CULTURAL CULTURALI E AMBIENTALI NONCHÉ AND ENVIRONMENTAL TREASURES, IL SISTEMA ECONOMICO-PRODUTTIVO AND ITS QUALITY ECONOMIC RACCONTAMI L’UMBRIA RACCONTAMI DI QUALITÀ DELLA REGIONE UMBRIA AND PRODUCTION SYSTEM RACCONTAMI L’UMBRIA STORIES ON UMBRIA EDIZIONE CONCORSO GIORNALISTICO • FESTIVAL INTERNAZIONALE DEL GIORNALISMO JOURNALISM AWARD • INTERNATIONAL JOURNALISM FESTIVAL 2015 PRESENTAZIONE // INTRODUCTION © Camera di Commercio di Perugia Eccoci di nuovo insieme a raccontare l’Umbria, inesauribile scrigno di bellezze, vera terra di emozioni. Coordinamento editoriale // Publishing coordinator A raccontare storie di questi luoghi e di questa gente. Paola Buonomo Storie talora al limite dell’incredibile, come quella di indomiti animalisti americani che, dopo aver passato una vita Progetto grafico e impaginazione // Graphic design and page make-up a contrastare baleniere in giro per il mondo, si ritrovano a raccogliere olive nella quiete di Paciano. Archi’s Comunicazione srl – Perugia Storie di singolari iniziative -

Pietro Scarpellini

©Ministero per beni e le attività culturali-Bollettino d'Arte PIETRO SCARPELLINI NOTE SULLA PITTURA DEL RINASCIMENTO NELLA GALLERIA NAZIONALE DELL'UMBRIA (A PROPOSITO DI UN RECENTE CA T ALOGO) Il secondo volume del catalogo scientifico della Galleria con le effigi tradizionali di Tommaso Parentucelli da Sar Nazionale dell'Umbria a Perugia (F. SANTI, Galleria Na zana, eletto papa il 6 marzo 1447, col nome appunto di zionale dell' Umbria. Dipinti, sculture, oggetti dei secoli XV, Niccolò V.3) Di qui un terminus post quem per l'esecuzione XVI, Roma, Istituto Poligrafico e Zecca dello Stato, 1985) del complesso che viene a collocarlo nel pieno dell'attività si apre con la scheda relativa al PoI ittico dei Domenicani romana, tra il 1447 ed il 1448, coinvolgendo nei tempi la del Beato Angelico in cui molto giustamente il Santi rico stessa affrescatura della Cappella Nicolina.4) nosce una quasi totale autografia, estesa anche a gran Ora tali ingegnose osservazioni lasciano però il margine parte della predella. Nessun dubbio difatti che ci si trovi a più di un dubbio. Per esempio, io credo che il Santi dinanzi ad una delle opere più belle del grande pittore, abbia ragione quando afferma, assieme con lo Zampetti, ove la qualità non scade mai o quasi mai, ed il cui ruolo che echi del lavoro dell' Angelico si avvertono già molto nelle vicende dell' arte umbra quattrocentesca è stato in evidenti tanto nella tavola principale quanto nella pre passato alquanto sottovalutato. Vorrei in proposito innan della della 'Madonna del Pergolato', opera di -

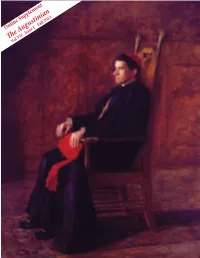

The Augustinian Vol VII

Online Supplement The Augustinian Vol VII . Issue I Fall 2012 Volume VII . Issue I The Augustinian Fall 2012 - Online Supplement Augustinian Cardinals Fr. Prospero Grech, O.S.A., was named by Pope Benedict XVI to the College of Cardinals on the Feast of the Epiphany, January 6, 2012. On February 18, 2012, when he received the red biretta, he joined the ranks of twelve other Augustinian Friars who have served as Cardinals. This line stretches back to 1378, when Bonaventura Badoardo da Padova, O.S.A., was named Cardinal, the first Augustinian Friar so honored. Starting with the current Cardinal, Prospero Grech, read a biographical sketch for each of the thirteen Augustinian Cardinals. Friars of the Province of Saint Thomas of Villanova Sebastiano Martinelli, O.S.A., the most recent Augustinian Cardinal prior to Cardinal Prospero Grech, O.S.A., served as Apostolic Delegate to the United States (1896 - 1902). While serving in this position, he made several trips to visit Augustinian sites. In 1897, while visiting Villanova, he was pho- tographed with the professed friars of the Province. Among these men were friars who served in leader- ship roles for the Province, at Villanova College, and in parishes and schools run by the Augustinians. Who were these friars and where did they serve? Read a sketch, taken from our online necrology, Historical information for Augustinian Cardinals for each of the 17 friars pictured with Archbishop supplied courtesy of Fr. Michael DiGregorio, O.S.A., Sebastiano Martinelli. Vicar General of the Order of St. Augustine. On the Cover: Thomas Eakins To read more about Archbishop Martinelli and Portrait of Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli, 1902 Cardinal Grech, see the Fall 2012 issue of The Oil on panel Augustinian magazine, by visiting: The Armand Hammer Collection http://www.augustinian.org/what-we-do/media- Gift of the Armand Hammer Foundation room/publications/publications Hammer Museum, Los Angeles Photo by Robert Wedemeyer Copyright © 2012, Province of St.