Agricultural Public Expenditure Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shankar Ias Academy Test 18 - Geography - Full Test - Answer Key

SHANKAR IAS ACADEMY TEST 18 - GEOGRAPHY - FULL TEST - ANSWER KEY 1. Ans (a) Explanation: Soil found in Tropical deciduous forest rich in nutrients. 2. Ans (b) Explanation: Sea breeze is caused due to the heating of land and it occurs in the day time 3. Ans (c) Explanation: • Days are hot, and during the hot season, noon temperatures of over 100°F. are quite frequent. When night falls the clear sky which promotes intense heating during the day also causes rapid radiation in the night. Temperatures drop to well below 50°F. and night frosts are not uncommon at this time of the year. This extreme diurnal range of temperature is another characteristic feature of the Sudan type of climate. • The savanna, particularly in Africa, is the home of wild animals. It is known as the ‘big game country. • The leaf and grass-eating animals include the zebra, antelope, giraffe, deer, gazelle, elephant and okapi. • Many are well camouflaged species and their presence amongst the tall greenish-brown grass cannot be easily detected. The giraffe with such a long neck can locate its enemies a great distance away, while the elephant is so huge and strong that few animals will venture to come near it. It is well equipped will tusks and trunk for defence. • The carnivorous animals like the lion, tiger, leopard, hyaena, panther, jaguar, jackal, lynx and puma have powerful jaws and teeth for attacking other animals. 4. Ans (b) Explanation: Rivers of Tamilnadu • The Thamirabarani River (Porunai) is a perennial river that originates from the famous Agastyarkoodam peak of Pothigai hills of the Western Ghats, above Papanasam in the Ambasamudram taluk. -

Sgp National Strategy Global Environment Facility (Gef Sgp) in the Republic of Tajikistan (2015-2018)

SGP NATIONAL STRATEGY GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY (GEF SGP) IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN (2015-2018) SGP NATIONAL STRATEGY GLOBAL ENVIRONMENT FACILITY (GEF SGP) IN THE REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN (2015-2018) Country: Tajikistan Funds for the sixth Operational Phase ($) ??? USD a. Funds of the GEF Small Grants Programme ??? USD b. Residual balance (for the fivth Operational Phase): ??? USD c. STAR funds: ??? USD d. Other funds which should be involved: ??? USD (project co –financing ) This strategy serves as a fundamental document for the Small Grants Programme of the Global Environment Facility in Tajikistan (hereinafter - the GEF SGP), determining the thematic and geographical scope of work of the GEF SGP in the country, as well as governing the rules and procedures of programme work. The National Strategy has been developed in accordance with the guidelines and strategic priorities of the GEF on the GEF-VI operational period (2015-2018), as well as the strategic priorities for the environmental preservation in the Republic of Tajikistan and the guidance documents of the GEF SGP for all participating countries. The National Programme Strategy to be reviewed for the next GEF–VII operational period. Table of Contents Acronyms 6 1. General information on the GEF SGP results in the framework of OP5 7 1.1. Brief summary of the GEF SGP Strategy in Tajikistan 9 1.2. Base terms for the GEF SGP in Tajikistan 11 Socio-economic context 11 Geographical context 11 Biodiversity context 13 Protected areas 13 Existing legal terms 13 Institutional context 15 2. Programme niche of the GEF SGP Country Strategy 16 Setting priorities 18 POPs / chemicals 22 Environmental management and economic benefits 25 Geographical and thematic coverage 27 2.1. -

Adivasis of India ASIS of INDIA the ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR an MRG INTERNA

Minority Rights Group International R E P O R T The Adivasis of India ASIS OF INDIA THE ADIV • 98/1 T TIONAL REPOR AN MRG INTERNA BY RATNAKER BHENGRA, C.R. BIJOY and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI THE ADIVASIS OF INDIA © Minority Rights Group 1998. Acknowledgements All rights reserved. Minority Rights Group International gratefully acknowl- Material from this publication may be reproduced for teaching or other non- edges the support of the Danish Ministry of Foreign commercial purposes. No part of it may be reproduced in any form for com- Affairs (Danida), Hivos, the Irish Foreign Ministry (Irish mercial purposes without the prior express permission of the copyright holders. Aid) and of all the organizations and individuals who gave For further information please contact MRG. financial and other assistance for this Report. A CIP catalogue record for this publication is available from the British Library. ISBN 1 897693 32 X This Report has been commissioned and is published by ISSN 0305 6252 MRG as a contribution to public understanding of the Published January 1999 issue which forms its subject. The text and views of the Typeset by Texture. authors do not necessarily represent, in every detail and Printed in the UK on bleach-free paper. in all its aspects, the collective view of MRG. THE AUTHORS RATNAKER BHENGRA M. Phil. is an advocate and SHIMREICHON LUITHUI has been an active member consultant engaged in indigenous struggles, particularly of the Naga Peoples’ Movement for Human Rights in Jharkhand. He is convenor of the Jharkhandis Organi- (NPMHR). She has worked on indigenous peoples’ issues sation for Human Rights (JOHAR), Ranchi unit and co- within The Other Media (an organization of grassroots- founder member of the Delhi Domestic Working based mass movements, academics and media of India), Women Forum. -

Mountains of Asia a Regional Inventory

International Centre for Integrated Asia Pacific Mountain Mountain Development Network Mountains of Asia A Regional Inventory Harka Gurung Copyright © 1999 International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development All rights reserved ISBN: 92 9115 936 0 Published by International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development GPO Box 3226 Kathmandu, Nepal Photo Credits Snow in Kabul - Madhukar Rana (top) Transport by mule, Solukhumbu, Nepal - Hilary Lucas (right) Taoist monastry, Sichuan, China - Author (bottom) Banaue terraces, The Philippines - Author (left) The Everest panorama - Hilary Lucas (across cover) All map legends are as per Figure 1 and as below. Mountain Range Mountain Peak River Lake Layout by Sushil Man Joshi Typesetting at ICIMOD Publications' Unit The views and interpretations in this paper are those of the author(s). They are not attributable to the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and do not imply the expression of any opinion concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Preface ountains have impressed and fascinated men by their majesty and mystery. They also constitute the frontier of human occupancy as the home of ethnic minorities. Of all the Mcontinents, it is Asia that has a profusion of stupendous mountain ranges – including their hill extensions. It would be an immense task to grasp and synthesise such a vast physiographic personality. Thus, what this monograph has attempted to produce is a mere prolegomena towards providing an overview of the regional setting along with physical, cultural, and economic aspects. The text is supplemented with regional maps and photographs produced by the author, and with additional photographs contributed by different individuals working in these regions. -

Elimination of Plasmodium Falciparum Malaria in Tajikistan Anatoly V

Kondrashin et al. Malar J (2017) 16:226 DOI 10.1186/s12936-017-1861-5 Malaria Journal CASE STUDY Open Access Elimination of Plasmodium falciparum malaria in Tajikistan Anatoly V. Kondrashin1*, Azizullo S. Sharipov2, Dilshod S. Kadamov2, Saifuddin S. Karimov2, Elkhan Gasimov3, Alla M. Baranova1, Lola F. Morozova1, Ekaterina V. Stepanova1, Natalia A. Turbabina1, Maria S. Maksimova1 and Evgeny N. Morozov1,4 Abstract Malaria was eliminated in Tajikistan by the beginning of the 1960s. However, sporadic introduced cases of malaria occurred subsequently probably as a result of transmission from infected mosquito Anopheles fying over river the Punj from the border areas of Afghanistan. During the 1970s and 1980s local outbreaks of malaria were reported in the southern districts bordering Afghanistan. The malaria situation dramatically changed during the 1990s follow- ing armed confict and civil unrest in the newly independent Tajikistan, which paralyzed health services including the malaria control activities and a large-scale malaria epidemic occurred with more than 400,000 malaria cases. The malaria epidemic was contained by 1999 as a result of considerable fnancial input from the Government and the international community. Although Plasmodium falciparum constituted only about 5% of total malaria cases, reduc- tion of its incidence was slower than that of Plasmodium vivax. To prevent increase in P. falciparum malaria both in terms of incidence and territory, a P. falciparum elimination programme in the Republic was launched in 200, jointly supported by the Government and the Global Fund for control of AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria. The main activities included the use of pyrethroids for the IRS with determined periodicity, deployment of mosquito nets, impregnated with insecticides, use of larvivorous fshes as a biological larvicide, implementation of small-scale environmental man- agement, and use of personal protection methods by population under malaria risk. -

The Political and Geographical Factors of Agrarian Change in Tajikistan

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Hofman, Irna; Visser, Oane Working Paper Geographies of transition: The political and geographical factors of agrarian change in Tajikistan Discussion Paper, No. 151 Provided in Cooperation with: Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Transition Economies (IAMO), Halle (Saale) Suggested Citation: Hofman, Irna; Visser, Oane (2014) : Geographies of transition: The political and geographical factors of agrarian change in Tajikistan, Discussion Paper, No. 151, Leibniz Institute of Agricultural Development in Transition Economies (IAMO), Halle (Saale), http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:gbv:3:2-34506 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/104004 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung -

Situational Analysis: State of Rehabilitation in Tajikistan

MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL PROTECTION OF THE POPULATION REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN Mobility and Function for all Disability and Rehabilitation Programme - Breaking Barriers to Include All MINISTRY OF HEALTH AND SOCIAL PROTECTION OF THE POPULATION REPUBLIC OF TAJIKISTAN SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS State of rehabilitation in Tajikistan Disability and Rehabilitation Programme Breaking Barriers to Include All Abstract This publication summarizes the current gap, need and opportunities for intervention in the field rehabilitation for persons with disabilities in Tajikistan. The situational analysis process was conducted by an intersectoral working group consisting of members from different ministries under the leadership of the Ministry of Health and Social Protection, Republic of Tajikistan and with technical support from the WHO Country Office, Tajikistan. It was undertaken in collaboration with different disability and development related stakeholders and adopted a realist synthesis approach, being responsive to the unique social, cultural, economical and political circumstances in the country. The evaluation focuses on rehabilitation policy and governance, service provisions and its impact on persons with disabilities in development of an inclusive, rights-based society with equal opportunity for all in Tajikistan. Keywords Situational Analysis: State of Rehabilitation in Tajikistan. 1. Persons with disabilities - statistics and numerical data. 2. Persons with disabilities – rehabilitation. 3. Delivery of health care. 4. Children with disabilities. 5. Education. 6. Employment. 7. Person with disabilities – Policy and services. I. World Health Organization. Address requests about publications of the WHO Regional Office for Europe to: Publications WHO Regional Office for Europe UN City, Marmorvej 51 DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Alternatively, complete an online request form for documentation, health information, or for permission to quote or translate, on the Regional Office website (http://www.euro.who.int/pubrequest). -

Compilation on Geography Questions

IASbaba.com Compilation on Geography Questions 1. With regard to the Western Himalayas and the Eastern Himalayas, consider the following 1. The ranges of the Eastern Himalayas are more continuous compared to Western Himalayas 2. The Western Himalayas receive most of the precipitation in the winter months and the Eastern Himalayas in the summer months 3. Eastern Himalayas are much greener and dense compared to Western Himalayas Choose the correct answer using the codes below. 1. 1 and 2 only 2. 2 and 3 only 3. 1 and 3 only 4. All of the above Solution: 2 Western Himalaya refers to the western half of the Himalayan Mountain region, stretching from Badakhshan in northeastern Afghanistan/southern Tajikistan, through Kashmir to Nepal. Eastern Himalaya is situated between Central Nepal in the west and Myanmar in the east, occupying southeast Tibet in China, Sikkim, North Bengal, Bhutan and North-East India. The western himalayas consists of the most continuous range and the loftiest peaks and compared to eastern Himalayas. The western Himalayas receive more precipitation from northwest in the winters, and eastern Himalayas receive more precipitation from southeastern monsoon in the summers. Due to higher temperature and perception, the Eastern Himalayas are far greener with forests than the Western Himalaya. 2. Consider the following statements 1. The peninsular plateau is composed mainly of igneous and metamorphic rocks 2. The Garo, Khasi and Jaintia Hills form a part of peninsular block. 3. The peninsular plateau is the oldest and most stable landmass in India, devoid of earthquakes or volcanic activity. Iasbaba.com Page 1 IASbaba.com Choose the correct answer using the codes below. -

Mapping Fragile Areas: Case Studies from Central Asia

Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance Mapping Fragile Areas: Case Studies from Central Asia Elizaveta Chmykh Eugenia Dorokhova Hine-Wai Loose Kristina Sutkaityte Rebecca Mikova Richard Steyne Sarabeth Murray Edited by dr Grazvydas Jasutis Mapping Fragile Areas: Case Studies from Central Asia About DCAF DCAF – Geneva Centre for Security Sector Governance is dedicated to improving the se- curity of states and their people within a framework of democratic governance, the rule of law, respect for human rights, and gender equality. Since its founding in 2000, DCAF has contributed to making peace and development more sustainable by assisting partner states, and international actors supporting these states, to improve the governance of their security sector through inclusive and participatory reforms. It creates innovative knowledge products, promotes norms and good practices, provides legal and policy advice and supports capacity-building of both state and non-state security sector stakeholders. DCAF’s Foundation Council is comprised of representatives of about 60 member states and the Canton of Geneva. Active in over 80 countries, DCAF is interna- tionally recognized as one of the world’s leading centres of excellence for security sector governance (SSG) and security sector reform (SSR). DCAF is guided by the principles of neutrality, impartiality, local ownership, inclusive participation, and gender equality. For more information visit www.dcaf.ch and follow us on Twitter @DCAF_Geneva. The views and opinions expressed in this study -

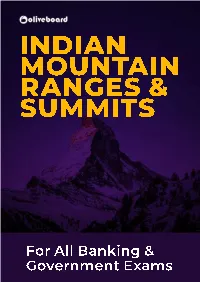

Indian Mountain Ranges & Summits

INDIAN MOUNTAIN RANGES & SUMMITS For All Banking & Government Exams Indian Mountain Ranges & Summits Free static GK e-book As we all know that General Awareness is one of the very important and prominent topics for any competitive exam. Keeping in mind the same, we have come up with some major mountain ranges and Himalayan summits in India. This will help you all the major Himalayan ranges related details which are often asked in various exams. With multiple upcoming exams this could be very helpful. Below are the few sneak peaks: Sikkim (Shared 1 Kanchenjunga 8,586 Himalayas with Nepal) 2 Ghent Kangri 7,401 Saltoro Karakoram Ladakh Arunachal 3 Kangto 7,060 Assam Himalaya Pradesh Mountain Ranges: Aravalli Range - starting in North India from Delhi and passing through southern Haryana, through to Western India across the states of Rajasthan and ending in Gujarat. To keep you updated with the major Himalayan ranges and summits found in India we bring you this e-book, read along and learn all about the important details and geographical locations of the mountain ranges found in India. Indian Mountain Ranges & Summits Free static GK e-book Mountain Summits Rank Mountain Height (m) Range State (Indian) Sikkim (Shared 1 Kanchenjunga 8,586 Himalayas with Nepal) 2 Nanda Devi 7,816 Garhwal Himalaya Uttarakhand 3 Kamet 7,756 Garhwal Himalaya Uttarakhand 4 Saltoro Kangri / K10 7,742 Saltoro Karakoram Ladakh 5 Saser Kangri I / K22 7,672 Saser Karakoram Ladakh 6 Mamostong Kangri / K35 7,516 Rimo Karakoram Ladakh 7 Saser Kangri II 7,513 Saser Karakoram -

The Contribution of Positive Youth Development In

THE CONTRIBUTION OF POSITIVE YOUTH DEVELOPMENT IN TAJIKISTAN TO EFFECTIVE PEACEBUILDING AND TO COUNTERING OR PREVENTING VIOLENT EXTREMISM: SUCCESSES, LIMITATIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS RESEARCH REPORT This report is made possible by the support of the American People through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), with support from the U.S. President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), under the terms of YouthPower Learning, Contract No. AID-OAA-I-15-00034/AID-OAA-TO-00011. The author’s views expressed in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government. Table of Contents Introduction………………………………………………………………….………4 Research Task and Goals Methodology and Research Approaches Background Information and Youth Statistics Chapter I. Mapping Youth and PVE Initiatives in Tajikistan…………………..16 1.0 Conceptual Framework 1.1 Government PVE and Youth Policy 1.2 International Organizations’ Programs 1.3 Tajik NGOs Chapter II. Analyzing Impact: Challenges, Successes and Obstacles………….49 2.0 Challenges and Successes 2.1 Limitations and Obstacles Conclusions and Recommendations………………………………………………55 3.0 Summarizing Remarks 3.1 Recommendations ANNEXES….………………………………………………………………….……59 Annex I. Dialogue and Confidence Building projects Annex II. Youth Empowering Projects and Initiatives Annex III Youth Education, Civic Education Initiatives Annex IV. Tajik NGOs’ Initiatives 1) Dushanbe NGOs’ Initiatives/ Summary of Interviews 2) Regional NGOs’ Initiatives/Summaries of Interviews 1 Abbreviations -

Elementary Tajik

Course Syllabus Elementary Tajik Instructors: Madina Djuraeva Email: [email protected] Office: 1235 Office Hours: TBA after negotiation with the students Class Schedule: Monday: 8.30AM-1PM Tuesday: 8.30AM-1PM. 4PM-CESSI lecture series. Students are strongly encouraged to attend these lectures. Students will be given extra credits for attending these lectures. Wednesday: 8.30AM-12PM 12PM-1PM: CESSI lunch at the Memorial Union Thursday: 8.30AM-1PM Friday: 8.30AM-10AM – Quiz 10-11AM: Dastarkhan 11AM-1PM: CESSI movie series A 10-minute break will be given after each hour. All the necessary handouts and homework will be given and assigned during the class. Required Textbooks Khojayori, N. (2009). Tajiki: An elementary textbook 1. Georgetown University Press. Khojayori, N. (2009). Tajiki: An elementary textbook 2. Georgetown University Press. Recommended book: Khojayori, N. & Thompson, M. (2009). Tajiki: Reference grammar for Beginners. Georgetown University Press. Note: You don’t have to purchase the reference book. Its content will be integrated into the instruction. Course Description and Objectives: Welcome to the summer intensive course of elementary Tajik. Tajik is a variety of Farsi based languages, which is spoken in Central Asia. Historically, Tajiks called their language zabani farsī, meaning Persian language in English; the term zaboni tojikī, or Tajik language, was introduced in the 20th century by the Soviets. Most speakers of Tajik live in Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. Tajik is the official language of Tajikistan. This course provides students with a general knowledge of the current spoken and written Tajik Language. It familiarizes students with the Tajik alphabet, common phrases used in real-life conversations and daily routines.