Mongol Invasion of Japan Time to Complete: Two 45-Minute Class Sessions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict Between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions

UNIVERSITY OF HAWAllllBRARI Powerful Warriors and Influential Clergy Interaction and Conflict between the Kamakura Bakufu and Religious Institutions A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN HISTORY MAY 2003 By Roy Ron Dissertation Committee: H. Paul Varley, Chairperson George J. Tanabe, Jr. Edward Davis Sharon A. Minichiello Robert Huey ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Writing a doctoral dissertation is quite an endeavor. What makes this endeavor possible is advice and support we get from teachers, friends, and family. The five members of my doctoral committee deserve many thanks for their patience and support. Special thanks go to Professor George Tanabe for stimulating discussions on Kamakura Buddhism, and at times, on human nature. But as every doctoral candidate knows, it is the doctoral advisor who is most influential. In that respect, I was truly fortunate to have Professor Paul Varley as my advisor. His sharp scholarly criticism was wonderfully balanced by his kindness and continuous support. I can only wish others have such an advisor. Professors Fred Notehelfer and Will Bodiford at UCLA, and Jeffrey Mass at Stanford, greatly influenced my development as a scholar. Professor Mass, who first introduced me to the complex world of medieval documents and Kamakura institutions, continued to encourage me until shortly before his untimely death. I would like to extend my deepest gratitude to them. In Japan, I would like to extend my appreciation and gratitude to Professors Imai Masaharu and Hayashi Yuzuru for their time, patience, and most valuable guidance. -

Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan

Eurasian Maritime History Case Study: Northeast Asia Thirteenth Century Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Dr. Grant Rhode Boston University Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and Japan | 2 Maritime History Case Study: Northeast Asia Thirteenth Century Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Contents Front piece: The Defeat of the Mongol Invasion Fleet Kamikaze, the ‘Divine Wind’ The Mongol Continental Vision Turns Maritime Mongol Naval Successes Against the Southern Song Korea’s Historic Place in Asian Geopolitics Ancient Pattern: The Korean Three Kingdoms Period Mongol Subjugation of Korea Mongol Invasions of Japan First Mongol Invasion of Japan, 1274 Second Mongol Invasion of Japan, 1281 Mongol Support for Maritime Commerce Reflections on the Mongol Maritime Experience Maritime Strategic and Tactical Lessons Limits on Mongol Expansion at Sea Text and Visual Source Evidence Texts T 1: Marco Polo on Kublai’s Decision to Invade Japan with Storm Description T 2: Japanese Traditional Song: The Mongol Invasion of Japan Visual Sources VS 1: Mongol Scroll: 1274 Invasion Battle Scene VS 2: Mongol bomb shells: earliest examples of explosive weapons from an archaeological site Selected Reading for Further Study Notes Maps Map 1: The Mongol Empire by 1279 Showing Attempted Mongol Conquests by Sea Map 2: Three Kingdoms Korea, Battle of Baekgang, 663 Map 3: Mongol Invasions of Japan, 1274 and 1281 Map 4: Hakata Bay Battles 1274 and 1281 Map 5: Takashima Bay Battle 1281 Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and -

An Accessible Vangobook™ That Focuses on the Connections Within and Between Societies

judge_langdonKIT_press 7/18/08 11:56 AM Page 1 Preview Chapter 15 Inside! An accessible VangoBook™ that focuses on the connections within and between societies. judge_langdonKIT_press 7/15/08 11:34 AM Page 2 Spring 2008 Dear Colleague: We are two professors who love teaching world history. For the past sixteen years, at our middle-sized college, we have team-taught a two-semester world history course that first-year students take to fulfill a college-wide requirement. Our students have very diverse backgrounds and interests. Most take world history only because it is required, and many of them find it very challenging. Helping them understand world history and getting them to share our enthusiasm for it are our main purposes and passions. To help our students prepare better for class and enhance their enjoyment of history, we decided to write a world history text that was tailored specifically to meet their needs. Knowing that they often see history as a bewildering array of details, dates, and developments, we chose a unifying theme— connections—and grouped our chapters to reflect the expansion of connections from regional to global levels. To help make our text more accessible, we wrote concise chapters in a simple yet engaging narrative, divided into short topical subsections, with pronunciations after difficult names and marginal notes highlighting our theme. Having seen many students struggle because they lack a good sense of geography, we included numerous maps—more than twice as many as most other texts—and worked hard to make them clear and consistent, with captions that help the students read the maps and connect them with surrounding text.We also provided compelling vignettes to introduce the themes of each chapter, concise excerpts from relevant primary sources, colorful illustrations,“perspective” summaries and chronologies, reflection questions, and useful lists of key concepts, key people, and additional sources. -

An Eighteenth Century Japanese Sailor's Record of Insular Southeast Asia

Magotaro: An Eighteenth CenturySari Japanese 27 (2009) Sailor’s 45 - 66 Record 45 Magotaro: An Eighteenth Century Japanese Sailor’s Record of Insular Southeast Asia NOMURA TORU ABSTRAK Walaupun dipanggil Magoshici, Mogataro, pengembara Jepun dari kurun ke 18 dan lahir barangkali pada 1747 ini dirujuk sebagai Magotaro berdasarkan transkrip wawancaranya di pejabat majistret di Nagasaki. Nama yang sama digunakan dalam rekod lain, iaitu Oyakugashira Kaisen Mokuroku, rekod bisnes pada keluarga Tsugami, agen perkapalan di kampong halamannya. Dalam kertas ini, saya cuba mengesan pengalamannya dalam beberapa buah dokumen dan rekod. Yang paling penting dan yang boleh dicapai adalah An Account of a Journey to the South Seas. Ia menyiarkan kisah daripada wawancara dengannya pada usia tuanya. Dokumen rasmi lain mengenainya adalah Ikoku Hyoryu Tsukamatsurisoro Chikuzen no Kuni Karadomari Magotaro Kuchigaki yang merupakan transkrip soal siasat ke atasnya di Pejabat Majisret di Nagasa bila dia tiba di Nagasaki pada 1771. Selain itu, terdapat juga Oranda Fusetsugaki Shusei yang diserahkan kepada Natsume Izumizunokami Nobumasa, majistret Nagasaki oleh Arend Willem Feith, kapten kapal Belanda yang membawa Magotaro dihantar balik ke Jepun. Sumber-sumber lain, termasuk manuskrip, mempunyai gaya sastera, tetapi kurang dipercayai. Kata kunci: Korea, Jepun, China, membuat kapal, pengangkutan marin, Banjarmasin ABSTRACT Although called Magoshichi, the eighteenth century Japanese adventurer, Mogataro, born probably in 1747, was referred to as Magotaro, based on the transcript of his interview at the Nagasaki Magistrate Office. The same name is used in another record, Oyakugashira Kaisen Mokuroku, a business record of the Tsugami family, a shipping agent in Magotaro’s home village. In this paper, I attempt to trace his experiences in a number of documents and records. -

Japan and Its East Asian Neighbors: Japan’S Perception of China and Korea and the Making of Foreign Policy from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century

JAPAN AND ITS EAST ASIAN NEIGHBORS: JAPAN’S PERCEPTION OF CHINA AND KOREA AND THE MAKING OF FOREIGN POLICY FROM THE SEVENTEENTH TO THE NINETEENTH CENTURY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Norihito Mizuno, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor James R. Bartholomew, Adviser Professor Philip C. Brown Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn Graduate Program in History Copyright by Norihito Mizuno 2004 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of Japanese perceptions of its East Asian neighbors – China and Korea – and the making of foreign policy from the early seventeenth century to the late nineteenth century. Previous studies have overwhelmingly argued that after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan started to modernize itself by learning from the West and changed its attitudes toward those neighboring countries. It supposedly abandoned its traditional friendship and reverence toward its neighbors and adopted aggressive and contemptuous attitudes. I have no intention of arguing here that the perspective of change and discontinuity in Japan’s attitudes toward its neighbors has no validity at all; Japan did adopt Western-style diplomacy toward its neighbors, paralleling the abandonment of traditional culture which had owed much to other East Asian civilizations since antiquity. In this dissertation, through examination primarily of official and private documents, I maintain that change and discontinuity cannot fully explain the Japanese policy toward its East Asian neighbors from the early seventeenth to the late nineteenth century. The Japanese perceptions and attitudes toward China and ii Korea had some aspects of continuity. -

2. Myth, Memory, and the Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan

ArchAism And AntiquAriAnism 2. Myth, Memory, and the Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan Thomas D. Conlan A set of two illustrated handscrolls commissioned by the warrior Takezaki Suenaga 竹崎季長 (1246–ca. 1324), who fought in defense against the two attempted Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281, provides insight into how picture scrolls were viewed and abused. Created sometime between the invasions and Suenaga’s death in the 1320s, his scrolls, called as the Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan (Mōko shūrai ekotoba 蒙古襲来絵詞), were known to only a few warrior families from northern Kyushu for five centuries before they became widely disseminated and appreciated in Japan.1 These scrolls were valued enough not to be discarded, but not thought precious enough to merit special care or conservation, and the images that survive have been badly damaged, with a number of pages and scenes missing.2 Some accidents contributed to alterations in the Mongol Scrolls—which changed hands several times and were copied repeatedly from the late eighteenth century—but others were intentional. Names of characters and images of figures and objects were added to scenes, as too were criticisms of artistic inaccuracies. The Ōyano大矢野, who owned the scrolls late in the sixteenth century, even scratched out Takezaki Suenaga’s name in one scene so as to emphasize the valor of their an- cestors.3 Other changes emphasize Suenaga’s role in the narrative at the expense of his brother-in-law Mii Saburō Sukenaga 三井三郎資長.4 Suenaga’s face has been redrawn repeatedly, with his complexion whitened considerably, and his name was inserted next to some figures at a much later date.5 Finally, what has been thought to be the oldest representation of an exploding shell (teppō 鉄砲) was in fact added to the scrolls during the mid-eighteenth century. -

Kofun Period: Research Trends 20071 Tsujita Jun’Ichirō2

Kofun Period: Research Trends 20071 Tsujita Jun’ichirō2 Introduction For the 2007 FY (Fiscal Year), there are two items worth noting not only for Kofun period research, but more broadly as trends for Japanese archaeology as a whole. One is the dismantling and conservation project for the Takamatsuzuka3 tomb, and the other is the partial realization of on-site inspections of tombs under the care of the Imperial Household Agency as imperial mausolea. The murals of Takamatsuzuka had been contaminated by mold and were in need of conservation, and in the end, the stone chamber was dismantled under the nation’s gaze, with step-by-step coverage of the process. The dismantling was completed without mishap, and conservation of the murals by the Agency for Cultural Affairs is planned for approximately the next ten years. Regarding the imperial mausolea, an on-site inspection was held of the Gosashi4 tomb in Nara prefecture, with access to the first terrace of the mound. The inspection provided new data including the 5 confirmation of rows of haniwa ceramics, bringing a variety of issues out in relief. It is hoped that inspections will be conducted continually in the future, through cooperation between the Imperial Household Agency and the academic associations involved. FY 2007 also saw the publication of vast numbers of reports, books, and articles on the Kofun period alone, and while there are too many to cover comprehensively here, the author will strive to grasp the trends of Kofun period research for the year as a whole from the literature he has been able to examine. -

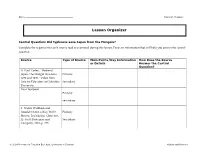

Lesson Organizer

Name _____________________________________ Handout (3 pages) Lesson Organizer Central Question: Did typhoons save Japan from the Mongols? Complete the organizer for each source read or examined during this lesson. Focus on information that will help you answer the central question. Source Type of Source Main Points/Key Information How Does the Source or Details Answer the Central Question? H. Paul Varley. “Medieval Japan: The Mongol Invasions: Primary 1274 and 1281.” Video from Asia for Educators at Columbia Secondary University. Your Textbook Primary Secondary T. Walter Wallbank and Arnold Schrier. Living World Primary History, 2nd edition. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Secondary Company, 1964, p. 243. © 2014 Program for Teaching East Asia, University of Colorado History and Memory T. Walter Wallbank et al. History and Life, 4th edition. Glenview, IL: Primary Scott, Foresman and Company, 1990, p. 317. Secondary Marvin Perry et al. A History of the World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Primary Company, 1985, pp. 264-265. Secondary Jerry H. Bentley and Herbert F. Ziegler. Traditions and Encounters: Primary A Global Perspective on the Past, 4th edition. Columbus, OH: McGraw Secondary Hill, 2008, p. 471. Iftikhar Ahmad et al. World Cultures: A Global Mosaic. Upper Primary Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001, 388-389. Secondary Albert M. Craig et al. The Heritage of World Civilization, Combined Primary edition, 4th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1997, p. Secondary 269. Elizabeth Gaynor Ellis and Anthony Esler. World History Primary Connections to Today. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, Secondary 2005, p. 321. © 2014 Program for Teaching East Asia, University of Colorado History and Memory Martin Colcutt. -

Japanese Cooking

Japanese Cooking By: April Thompson, NCTA Ohio 2017 Subject: Ancient World History Grade: 7th Content Statement: 16 – The ability to understand individual and group perspectives is essential to analyzing historic and contemporary issues. Content Statement: 4 – Mongol influence led to unified states in China and Korea, but the Mongol failure to conquer Japan allowed a feudal system to persist. Content Statement: 8 – Empires in Africa (Ghana, Mali and Songhay) and Asia (Byzantine, Ottoman, Mughal and China) grew as commercial and cultural centers along trade routes. 5. Lesson 1 Japanese Cooking Academic Content Standards: Content Statement: 16 – The ability to understand individual and group perspectives is essential to analyzing historic and contemporary issues. Essential Question: What is the primary agricultural product produced in Japan? How does this impact the diet of Japanese children? What type of snack might a Japanese child eat? Objective: ● Students will link previously learned information about the history of Japanese Feudalism and geography (below). ● Students will learn the importance of Rice to Japanese society. ● Students will prepare a Japanese recipe for Rice Balls. ● Students will compare and contrast a Japanese Rice Ball to an American lunch food-- ham sandwich on white bread. Materials: (prior to this lesson) Printed copies of Climate and Geographical Feature, Japanese Feudalism and The Mongols Try to Invade Japan (attached) Chromebooks (to read from) or printed copies of RICE Printed copies of Onigiri 101: How to Make Japanese Rice Balls Previously prepared Japanese cooked rice (enough for each child to make a ball)**It is important that you use Japanese rice since a certain stickiness is required for the balls to hold together Add-in ingredients such as tuna, cooked chicken, smoked salmon Nori (roasted seaweed. -

Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan

Maritime History Case Study Guide: Northeast Asia Thirteenth Century Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Study Guide Prepared By Eytan Goldstein Lyle Goldstein Grant Rhode Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and Japan Study Guide | 2 Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Study Guide Contents Decision Point Questions: The following six “Decision Point Questions” (DPQs) span the Mongol actions from 1270 through 1286 in a continuum. Case 1, the initial decision to invade, and Case 6, regarding a hypothetical third invasion, are both big strategic questions. The other DPQs chronologically in between are more operational and tactical, providing a strong DPQ mix for consideration. Case 1 The Mongol decision whether or not to invade Japan (1270) Case 2 Decision to abandon Hakata Bay (1274) Case 3 Song capabilities enhance Mongol capacity at sea (1279) Case 4 Mongol intelligence collection and analysis (1275–1280) Case 5 Rendezvous of the Mongol fleets in Imari Bay (1281) Case 6 Possibility of a Third Mongol Invasion (1283–1286) Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and Japan Study Guide | 3 Case 1: The Mongol decision whether or not to invade Japan (1270) Overview: The Mongols during the thirteenth century built a nearly unstoppable war machine that delivered almost the whole of the Eurasian super continent into their hands by the 1270s. These conquests brought them the treasures of Muscovy, Baghdad, and even that greatest prize of all: China. Genghis Khan secured northern China under the Jin early on, but it took the innovations of his grandson Kublai Khan to finally break the stubborn grip of the Southern Song, which they only achieved after a series of riverine campaigns during the 1270s. -

Whiteness, Japanese-Ness, and Resistance in Sūkyō Mahikari in the Brazilian Amazon S

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2018 Raça, Jinshu, Race: Whiteness, Japanese-ness, and Resistance in Sūkyō Mahikari in the Brazilian Amazon Moana Luri de Almeida University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, and the International and Intercultural Communication Commons Recommended Citation de Almeida, Moana Luri, "Raça, Jinshu, Race: Whiteness, Japanese-ness, and Resistance in Sūkyō Mahikari in the Brazilian Amazon" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1428. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1428 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. RAÇA, JINSHU, RACE: WHITENESS, JAPANESE-NESS, AND RESISTANCE IN SŪKYŌ MAHIKARI IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZON __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Moana Luri de Almeida June 2018 Advisor: Christina R. Foust ©Copyright by Moana Luri de Almeida 2018 All Rights Reserved Author: Moana Luri de Almeida Title: RAÇA, JINSHU, RACE: WHITENESS, JAPANESE-NESS, AND RESISTANCE IN SŪKYŌ MAHIKARI IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZON Advisor: Christina R. Foust Degree Date: June 2018 Abstract This dissertation presented an analysis of how leaders and adherents of a Japanese religion called Sūkyō Mahikari understand and interpret jinshu (race) and hito (person) in a particular way, and how this ideology is practiced in the city of Belém, in the Brazilian Amazon. -

Conservation and Rehabilitation of Habitats for Key Migratory Birds in North-East Asia with Special Emphasis on Cranes and Black-Faced Spoonbills

(DRAFT) PROJECT REPORT Conservation and Rehabilitation of Habitats for Key Migratory Birds in North-East Asia with special emphasis on Cranes and Black-faced Spoonbills Edited by Korean Society of Environment and Ecology (KSEE) Edited by Sunyoung Park (Ms.) [email protected] Conservation Programme Advisor, WWF-Korea Korean Society of Environment and Ecology (KSEE) The Korean Society of Environment and Ecology (KSEE) was founded in 1987 and is designed to make a significant contribution to a sustainable development of human being and an improved global environment by conducting research, providing and applying the research results in the areas of Ecosystem Management & Conservation, Environmental Education and Ecosystem Restoration. Address: (06130) #910, 22, Teheran-ro 7-gil, Gangnam-gu, Seoul, 06130, Korea Tel: +82-70-4194-7488 Fax: 82-70-4145-7488 E-mail: [email protected] Homepage: http://www.enveco.org Disclaimer The views expressed in this report are those of editor and/or KSEE and do not necessarily reflect any opinion or policy of NEASPEC and/or UNESCAP-ENEA office. Cover image Copyright © KIM Yeonsoo Recommended Citation KSEE (ed.) 2016. Conservation and Rehabilitation of Key Habitats for Key Migratory Birds in North-East Asia with special emphasis on Cranes and Black-faced Spoonbills (2013-2016). Incheon: UNESCAP-ENEA and NEASPEC Acronyms and abbreviations BFS Black-faced Spoonbill CCZ Civilian Control Zone (ROK) DIPA Dauria International Protected Area DMZ De-militarized Zone DTMN Dauria Transboundary Monitoring Network