Answering “How Should We Rule China?”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan

Eurasian Maritime History Case Study: Northeast Asia Thirteenth Century Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Dr. Grant Rhode Boston University Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and Japan | 2 Maritime History Case Study: Northeast Asia Thirteenth Century Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Contents Front piece: The Defeat of the Mongol Invasion Fleet Kamikaze, the ‘Divine Wind’ The Mongol Continental Vision Turns Maritime Mongol Naval Successes Against the Southern Song Korea’s Historic Place in Asian Geopolitics Ancient Pattern: The Korean Three Kingdoms Period Mongol Subjugation of Korea Mongol Invasions of Japan First Mongol Invasion of Japan, 1274 Second Mongol Invasion of Japan, 1281 Mongol Support for Maritime Commerce Reflections on the Mongol Maritime Experience Maritime Strategic and Tactical Lessons Limits on Mongol Expansion at Sea Text and Visual Source Evidence Texts T 1: Marco Polo on Kublai’s Decision to Invade Japan with Storm Description T 2: Japanese Traditional Song: The Mongol Invasion of Japan Visual Sources VS 1: Mongol Scroll: 1274 Invasion Battle Scene VS 2: Mongol bomb shells: earliest examples of explosive weapons from an archaeological site Selected Reading for Further Study Notes Maps Map 1: The Mongol Empire by 1279 Showing Attempted Mongol Conquests by Sea Map 2: Three Kingdoms Korea, Battle of Baekgang, 663 Map 3: Mongol Invasions of Japan, 1274 and 1281 Map 4: Hakata Bay Battles 1274 and 1281 Map 5: Takashima Bay Battle 1281 Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and -

An Accessible Vangobook™ That Focuses on the Connections Within and Between Societies

judge_langdonKIT_press 7/18/08 11:56 AM Page 1 Preview Chapter 15 Inside! An accessible VangoBook™ that focuses on the connections within and between societies. judge_langdonKIT_press 7/15/08 11:34 AM Page 2 Spring 2008 Dear Colleague: We are two professors who love teaching world history. For the past sixteen years, at our middle-sized college, we have team-taught a two-semester world history course that first-year students take to fulfill a college-wide requirement. Our students have very diverse backgrounds and interests. Most take world history only because it is required, and many of them find it very challenging. Helping them understand world history and getting them to share our enthusiasm for it are our main purposes and passions. To help our students prepare better for class and enhance their enjoyment of history, we decided to write a world history text that was tailored specifically to meet their needs. Knowing that they often see history as a bewildering array of details, dates, and developments, we chose a unifying theme— connections—and grouped our chapters to reflect the expansion of connections from regional to global levels. To help make our text more accessible, we wrote concise chapters in a simple yet engaging narrative, divided into short topical subsections, with pronunciations after difficult names and marginal notes highlighting our theme. Having seen many students struggle because they lack a good sense of geography, we included numerous maps—more than twice as many as most other texts—and worked hard to make them clear and consistent, with captions that help the students read the maps and connect them with surrounding text.We also provided compelling vignettes to introduce the themes of each chapter, concise excerpts from relevant primary sources, colorful illustrations,“perspective” summaries and chronologies, reflection questions, and useful lists of key concepts, key people, and additional sources. -

Mongol Invasion of Japan Time to Complete: Two 45-Minute Class Sessions

Barbara Huntwork TIP April 4, 2013 Lesson Title: Mongol Invasion of Japan Time to Complete: Two 45-minute class sessions Lesson Objectives: Students will learn that: Samurai and shoguns took over Japan as emperors lost influence. Samurai warriors lived honorably. Order broke down when the power of the shoguns was challenged by invaders and rebellions. Strong leaders took over and reunified Japan. Academic Content Standards: 7th-Grade Social Studies Mongol influence led to unified states in China and Korea, but the Mongol failure to conquer Japan allowed a feudal system to persist. Maps and other geographic representations can be used to trace the development of human settlement over time. Geographic factors promote or impede the movement of people, products, and ideas. The ability to understand individual and group perspectives is essential to analyzing historic and contemporary issues. Literacy in History/Social Studies Cite specific textual evidence to support analysis of primary and secondary sources. Determine the central ideas or information of a primary or secondary source. Integrate visual information (e.g., in charts, graphs, photographs, videos, or maps) with other information in print and digital texts. Procedures 1. Section Preview – Read and ask students for response – You are a Japanese warrior, proud of your fighting skills. For many years you’ve been honored by most of society, but you face an awful dilemma. When you became a warrior, you swore to protect and fight for both your lord and your emperor. Now your lord has gone to war against the emperor, and both sides have called for you to join them. -

Japan and Its East Asian Neighbors: Japan’S Perception of China and Korea and the Making of Foreign Policy from the Seventeenth to the Nineteenth Century

JAPAN AND ITS EAST ASIAN NEIGHBORS: JAPAN’S PERCEPTION OF CHINA AND KOREA AND THE MAKING OF FOREIGN POLICY FROM THE SEVENTEENTH TO THE NINETEENTH CENTURY DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Norihito Mizuno, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2004 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor James R. Bartholomew, Adviser Professor Philip C. Brown Adviser Professor Peter L. Hahn Graduate Program in History Copyright by Norihito Mizuno 2004 ABSTRACT This dissertation is a study of Japanese perceptions of its East Asian neighbors – China and Korea – and the making of foreign policy from the early seventeenth century to the late nineteenth century. Previous studies have overwhelmingly argued that after the Meiji Restoration of 1868, Japan started to modernize itself by learning from the West and changed its attitudes toward those neighboring countries. It supposedly abandoned its traditional friendship and reverence toward its neighbors and adopted aggressive and contemptuous attitudes. I have no intention of arguing here that the perspective of change and discontinuity in Japan’s attitudes toward its neighbors has no validity at all; Japan did adopt Western-style diplomacy toward its neighbors, paralleling the abandonment of traditional culture which had owed much to other East Asian civilizations since antiquity. In this dissertation, through examination primarily of official and private documents, I maintain that change and discontinuity cannot fully explain the Japanese policy toward its East Asian neighbors from the early seventeenth to the late nineteenth century. The Japanese perceptions and attitudes toward China and ii Korea had some aspects of continuity. -

2. Myth, Memory, and the Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan

ArchAism And AntiquAriAnism 2. Myth, Memory, and the Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan Thomas D. Conlan A set of two illustrated handscrolls commissioned by the warrior Takezaki Suenaga 竹崎季長 (1246–ca. 1324), who fought in defense against the two attempted Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281, provides insight into how picture scrolls were viewed and abused. Created sometime between the invasions and Suenaga’s death in the 1320s, his scrolls, called as the Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan (Mōko shūrai ekotoba 蒙古襲来絵詞), were known to only a few warrior families from northern Kyushu for five centuries before they became widely disseminated and appreciated in Japan.1 These scrolls were valued enough not to be discarded, but not thought precious enough to merit special care or conservation, and the images that survive have been badly damaged, with a number of pages and scenes missing.2 Some accidents contributed to alterations in the Mongol Scrolls—which changed hands several times and were copied repeatedly from the late eighteenth century—but others were intentional. Names of characters and images of figures and objects were added to scenes, as too were criticisms of artistic inaccuracies. The Ōyano大矢野, who owned the scrolls late in the sixteenth century, even scratched out Takezaki Suenaga’s name in one scene so as to emphasize the valor of their an- cestors.3 Other changes emphasize Suenaga’s role in the narrative at the expense of his brother-in-law Mii Saburō Sukenaga 三井三郎資長.4 Suenaga’s face has been redrawn repeatedly, with his complexion whitened considerably, and his name was inserted next to some figures at a much later date.5 Finally, what has been thought to be the oldest representation of an exploding shell (teppō 鉄砲) was in fact added to the scrolls during the mid-eighteenth century. -

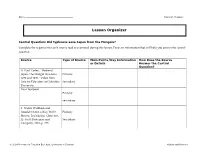

Lesson Organizer

Name _____________________________________ Handout (3 pages) Lesson Organizer Central Question: Did typhoons save Japan from the Mongols? Complete the organizer for each source read or examined during this lesson. Focus on information that will help you answer the central question. Source Type of Source Main Points/Key Information How Does the Source or Details Answer the Central Question? H. Paul Varley. “Medieval Japan: The Mongol Invasions: Primary 1274 and 1281.” Video from Asia for Educators at Columbia Secondary University. Your Textbook Primary Secondary T. Walter Wallbank and Arnold Schrier. Living World Primary History, 2nd edition. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman and Secondary Company, 1964, p. 243. © 2014 Program for Teaching East Asia, University of Colorado History and Memory T. Walter Wallbank et al. History and Life, 4th edition. Glenview, IL: Primary Scott, Foresman and Company, 1990, p. 317. Secondary Marvin Perry et al. A History of the World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Primary Company, 1985, pp. 264-265. Secondary Jerry H. Bentley and Herbert F. Ziegler. Traditions and Encounters: Primary A Global Perspective on the Past, 4th edition. Columbus, OH: McGraw Secondary Hill, 2008, p. 471. Iftikhar Ahmad et al. World Cultures: A Global Mosaic. Upper Primary Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2001, 388-389. Secondary Albert M. Craig et al. The Heritage of World Civilization, Combined Primary edition, 4th edition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1997, p. Secondary 269. Elizabeth Gaynor Ellis and Anthony Esler. World History Primary Connections to Today. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall, Secondary 2005, p. 321. © 2014 Program for Teaching East Asia, University of Colorado History and Memory Martin Colcutt. -

Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan

Maritime History Case Study Guide: Northeast Asia Thirteenth Century Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Study Guide Prepared By Eytan Goldstein Lyle Goldstein Grant Rhode Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and Japan Study Guide | 2 Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia Korea and Japan Study Guide Contents Decision Point Questions: The following six “Decision Point Questions” (DPQs) span the Mongol actions from 1270 through 1286 in a continuum. Case 1, the initial decision to invade, and Case 6, regarding a hypothetical third invasion, are both big strategic questions. The other DPQs chronologically in between are more operational and tactical, providing a strong DPQ mix for consideration. Case 1 The Mongol decision whether or not to invade Japan (1270) Case 2 Decision to abandon Hakata Bay (1274) Case 3 Song capabilities enhance Mongol capacity at sea (1279) Case 4 Mongol intelligence collection and analysis (1275–1280) Case 5 Rendezvous of the Mongol fleets in Imari Bay (1281) Case 6 Possibility of a Third Mongol Invasion (1283–1286) Mongol Invasions of Northeast Asia: Korea and Japan Study Guide | 3 Case 1: The Mongol decision whether or not to invade Japan (1270) Overview: The Mongols during the thirteenth century built a nearly unstoppable war machine that delivered almost the whole of the Eurasian super continent into their hands by the 1270s. These conquests brought them the treasures of Muscovy, Baghdad, and even that greatest prize of all: China. Genghis Khan secured northern China under the Jin early on, but it took the innovations of his grandson Kublai Khan to finally break the stubborn grip of the Southern Song, which they only achieved after a series of riverine campaigns during the 1270s. -

Whiteness, Japanese-Ness, and Resistance in Sūkyō Mahikari in the Brazilian Amazon S

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 1-1-2018 Raça, Jinshu, Race: Whiteness, Japanese-ness, and Resistance in Sūkyō Mahikari in the Brazilian Amazon Moana Luri de Almeida University of Denver Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Ethnic Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, and the International and Intercultural Communication Commons Recommended Citation de Almeida, Moana Luri, "Raça, Jinshu, Race: Whiteness, Japanese-ness, and Resistance in Sūkyō Mahikari in the Brazilian Amazon" (2018). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1428. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1428 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. RAÇA, JINSHU, RACE: WHITENESS, JAPANESE-NESS, AND RESISTANCE IN SŪKYŌ MAHIKARI IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZON __________ A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of Social Sciences University of Denver __________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy __________ by Moana Luri de Almeida June 2018 Advisor: Christina R. Foust ©Copyright by Moana Luri de Almeida 2018 All Rights Reserved Author: Moana Luri de Almeida Title: RAÇA, JINSHU, RACE: WHITENESS, JAPANESE-NESS, AND RESISTANCE IN SŪKYŌ MAHIKARI IN THE BRAZILIAN AMAZON Advisor: Christina R. Foust Degree Date: June 2018 Abstract This dissertation presented an analysis of how leaders and adherents of a Japanese religion called Sūkyō Mahikari understand and interpret jinshu (race) and hito (person) in a particular way, and how this ideology is practiced in the city of Belém, in the Brazilian Amazon. -

The Year of the Kamikaze by John T

P h o to co ute sy o f N a tio n a l Arch ive s The Year of the Kamikaze By John T. Correll s Japan entered the final year of World War II in the fall of 1944, its once-fearsome air forces were severely diminished, especially The suicide pilots were sent to die for the Athe carriers and aircraft of the imperial Japanese navy. emperor—regardless of what the emperor The Japanese had at first extended their perimeter in a big loop that encompassed thought about it. Southeast Asia, the Dutch East Indies, Wake Island, and the tip of the Aleutian chain in the Bering Sea. The reversal be- Smoke engulfs USS B u nk e il l , hit by two kamikazes off Okinawa May 11, 1945. gan in 1942 with the loss of four aircraft Losses included 400 US seamen killed or missing, 164 wounded, and 70 aircraft carriers at Midway and continued to the destroyed. “Marianas Turkey Shoot” in June 1944, where US forces gutted what was left of Japanese naval airpower and secured bases from which B-29 bombers could strike the Japanese home islands. The A6M Zero fighter had lost its quality edge to the US Navy’s FGF Hellcat and F4U Corsair and the Army Air Force’s P-38 Lightning. Experience and training levels fell as Japan’s best pilots were killed in action. The US was steadily rolling back the perimeter, with Gen. Douglas MacArthur moving northward from New Guinea and Adm. Chester W. Nimitz “island hopping” across the central Pacific. -

Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba (“Illustrated Account of the Mongol Invasions”): a Case Study of Encounter with the Other in Japan

MONOGRAPHIC Eikón Imago e-ISSN: 2254-8718 Mōko shūrai ekotoba (“Illustrated Account of the Mongol Invasions”): A Case Study of Encounter with the Other in Japan Giuseppina Aurora Testa1 Recibido: 15 de mayo de 2020 / Aceptado: 5 de junio de 2020 / Publicado: 3 de julio de 2020 Abstract. This paper is a study of a Japanese illustrated handscroll produced in the late Kamakura period (1185-1333), the Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba, that provides an invaluable pictorial account of the two attempted Mongol invasions of Japan in the years 1274 and 1281. It was copied and restored, with some images significantly altered, during the Edo period (1615-1868). While in the original handscroll the appearances of the foreign Mongols were depicted as accurately as possible, the figures added later show exaggerated features and distortions that correspond to new modes of imagining and representing peoples reflecting a new language and the shifting cosmologies brought about by the Japanese encounter with more “different” Others (Europeans). Keywords: Mongol; Emaki; Handscroll; Japan; Other. [es] Mōko shūrai ekotoba (“Manuscrito ilustrado de las invasiones mongoles”): un estudio de caso de encuentro con El Otro en Japón Resumen. Este artículo resulta del estudio de un manuscrito ilustrado japonés, producido a finales del periodo Kamakura (1185-1333), el Mōko Shūrai Ekotoba, que proporciona un valioso relato pictórico de las dos tentativas de invasión mongola de Japón en los años 1274 y 1281. Fue copiado y restaurado, con algunas imágenes significativamente alteradas, durante el período Edo (1615-1868). Mientras que en el manuscrito original las apariciones de los mongoles extranjeros fueron representadas con la mayor precisión posible, las figuras que se añadieron más tarde muestran rasgos exagerados y algo distorsionados que corresponden a los nuevos modos de imaginar y representar a los pueblos reflejando un nuevo lenguaje y las cosmologías cambiantes producidas por el encuentro japonés con otros más "diferentes" (europeos). -

The Kamikaze'srise Over the Course of Japanese History

Volume 10 Issue 2 (2021) Divine Winds and Human Waves: The Kamikaze’s rise over the Course of Japanese History ShaoYuan Su1 and Andrew R. Wilson1 1Cary Academy, Cary, NC, USA DOI: https://doi.org/10.47611/jsrhs.v10i2.1456 ABSTRACT Japan's World War II Kamikaze-attack strategy has become common knowledge to almost all Americans, with many sharing a preconception of fanatical and desperate Japanese pilots willfully crashing into American ships; however, this essay will demonstrate that the progression to suicidal aircraft attacks evolved gradually over the course of Japa- nese history. The roots of Kamikaze extend as far back as the Mongol Invasions of Japan, and it rose to prominence first during the Meiji Restoration and then with Nogi's actions during the Russo-Japanese war. This paper will trace the progression of Kamikaze throughout Japanese history to explain how a sequence of events, some directed by chance and others directed by commanders, culminated in Japan’s purpose-built, manned flying bombs that emerge in the Second World War. Understanding the historical context of Kamikaze and its logical evolution over time will help dispel the commonly held preconception of the singularly devoted but maniacally deranged Japanese soldier. Introduction On April 6, 1945, the peaceful blue skies above the Japanese island of Okinawa suddenly filled with hundreds of Japanese Kamikaze aircraft speeding towards the U.S. Fifth Fleet stationed offshore in support of the American ground offensive. The Fifth Fleet had faced sporadic Kamikaze attacks, most notably at the battle of Leyte Gulfi, but this was the first large-scale coordinated offensive launched by the Japanese. -

A Fluvially Derived Flood Deposit Dating to the Kamikaze Typhoons Near

Natural Hazards (2019) 99:827–841 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11069-019-03777-z ORIGINAL PAPER A fuvially derived food deposit dating to the Kamikaze typhoons near Nagasaki, Japan Caroline Ladlow1 · Jonathan D. Woodruf1 · Timothy L. Cook1 · Hannah Baranes1 · Kinuyo Kanamaru2 Received: 26 March 2019 / Accepted: 28 August 2019 / Published online: 4 September 2019 © Springer Nature B.V. 2019 Abstract Previous studies in western Kyushu revealed prominent marine-derived food deposits that date to the late thirteenth-century and are interpreted to be a result of two legendary typhoons linked to the failed Mongol invasions of Japan in 1274 and 1281. The regional persistence and prominence of sediments dating to these “Kamikaze” typhoon events (meaning divine wind) raise questions about the origins of these late thirteenth-century deposits. This is due in part to uncertainty in distinguishing between tsunami and storm- induced deposition. To provide additional insight into the true cause of prominent late thirteenth-century food deposits in western Kyushu, we present a detailed assessment of an additional event deposit dating to the late thirteenth-century from Lake Kawahara near Nagasaki, Japan. This particular deposit thickens landward towards the primary river fow- ing into Lake Kawahara and exhibits anomalously low Sr/Ti ratios that are consistent with a fuvial rather than a marine sediment source. When combined with previous food recon- structions, results support the occurrence of an extreme, late thirteenth-century event that was associated with both intense marine- and river-derived fooding. Results therefore con- tribute to a growing line of evidence for the Kamikaze typhoons resulting in widespread fooding in the region, rather than the late thirteenth-century deposit being associated with a signifcant tsunami impact to western Kyushu.