'Curiously Enchased' Goldsmiths & Diplomats in Baroque Europe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The State Hermitage Museum Annual Report 2012

THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT n 2012 CONTENTS General Editor 4 Year of Village and Garden Mikhail Piotrovsky, General Director of the State Hermitage Museum, 6 State Hermitage Museum. General Information Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 16 Awards Full Member of the Russian Academy of Arts, Professor of St. Petersburg State University, 20 Composition of the Hermitage Collection as of 1 January 2013 Doctor of History 40 Exhibitions 86 Restoration and Conservation 121 Publications EDITORIAL BOARD: 135 Electronic Editions and Video Films Mikhail Piotrovsky, 136 Conferences General Director of the State Hermitage Museum 141 Dissertations Georgy Vilinbakhov, 142 Archaeological Expeditions Deputy Director for Research 158 Major Construction and Restoration of the Buildings Svetlana Adaksina, Deputy Director, Chief Curator 170 Structure of Visits to the State Hermitage in 2012 Marina Antipova, 171 Educational Events Deputy Director for Finance and Planning 180 Special Development Programmes Alexey Bogdanov, Deputy Director for Maintenance 188 International Advisory Board of the State Hermitage Museum Vladimir Matveyev, 190 Guests of the Hermitage Deputy Director for Exhibitions and Development 194 Hermitage Friends Organisations Mikhail Novikov, 204 Hermitage Friends’ Club Deputy Director for Construction 206 Financial Statements of the State Hermitage Museum Mariam Dandamayeva, Academic Secretary 208 Principal Patrons and Sponsors of the State Hermitage Museum in 2012 Yelena Zvyagintseva, 210 Staff Members of -

The State Hermitage Museum Annual Report 2010 the State Hermitage Museum Annual Report 2010 Contents

The STaTe hermiTage muSeum annual reporT 2010 The STaTe hermiTage muSeum annual reporT 2010 conTenTS General Editor a year of two staircases ............................................................. 4 Mikhail Piotrovsky, Director of the state Hermitage Museum, The State Hermitage Museum. General Information ............... 6 Corresponding Member of the Russian academy of sciences, Full Member of the Russian academy of arts, Awards .......................................................................................... 12 Professor of st. Petersburg state University, Doctor of sciences (History) Composition of the Hermitage Collections as of 1 January 2011 .................................................................... 14 ediTorial Board: Permanent Exhibitions ............................................................... 27 Mikhail Piotrovsky, temporary Exhibitions ............................................................... 30 Director of the state Hermitage Museum Georgy Vilinbakhov, Restoration and Conservation .................................................... 70 Deputy Director for Research Publications ................................................................................. 85 Svetlana Adaksina, Conferences ................................................................................. 96 Deputy Director, Chief Curator Marina Antipova, Dissertations ................................................................................ 99 Deputy Director for Finance and Planning Archaeological Expeditions ...................................................... -

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, 135 Stranger’S Galleries, 114 Ye Olde Watling, 194 Summerill & Bishop, 169 Young Vic, 179–180

11_037407 bindex.qxp 10/13/06 3:45 PM Page 199 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes below. GENERAL INDEX Boots the Chemist, 161 Abbey Treasure Museum, 128–129 Bow Wine Vaults, 188–189 ACAVA, 160 British Airways London Eye, 152 Accessorize, 167 British Library, 136–137 Accommodations, 41–69 British Museum, 108–109 Admiral Duncan, 196 Buckingham Palace, 112–113 Ain’t Nothing But Blues Bar, 183 The Bull & Gate, 185 Airlines and airports, 12–15 Bull’s Head, 183 Alfie’s Antique Market, 159 Burberry, 164 Almeida Theatre, 179 Burlington Arcade, 155–156 American Bar, 195 Buses, 33 Anchor, 189 Annie’s Vintage Clothes, 169 Antiques, 159–160 Cabinet War Rooms, 131–132 Apple Market, 172 Cadogan Hall, 177 Apsley House, 135 Calendar of events, 6–10 Arnolfini Portrait, 117 Canary Wharf, 22, 77–78 The Ascot Festival, 10 Candy Bar, 197 Asprey & Garrard, 170 Cantaloupe, 195 ATMs, 4–5 Carlyle’s House, 134 Austin Reed, 164 Carnaby Street, 166 Cecil Sharpe House, 183–184 Ceremony of the Keys, 125 Banqueting House, 130 Changing of the Guard, 112–113, 132 Barbican Centre, 180 Chelsea, 29–30, 60, 101–102 Barbican Theatre, 177 Chelsea Antiques Fair, 9 Barcode, 196 Chelsea Flower Show, 7 Bar Rumba, 186 Children’s Book Centre, 162 Bars and cocktail lounges, 195–196 Churches and cathedrals, 129–130 Bayswater Road, 173 Churchill Museum, 131–132 Beauchamp Tower, 123 Cittie of Yorke, 189 Beau Monde, 164 The City, 17, 18–19, 70–75 Belgravia, 28–29, 59–60 City Hall, 132 Belinda Robertson, 163 Clarence House, 113 Benjamin Franklin House, 131 Classical music, -

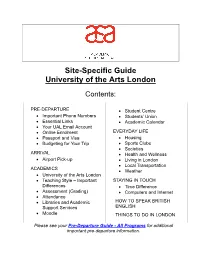

Site-Specific Guide University of the Arts London

Site-Specific Guide University of the Arts London Contents: PRE-DEPARTURE • Student Centre • Important Phone Numbers • Students’ Union • Essential Links • Academic Calendar • Your UAL Email Account • Online Enrolment EVERYDAY LIFE • Passport and Visa • Housing • Budgeting for Your Trip • Sports Clubs • Societies ARRIVAL • Health and Wellness • Airport Pick-up • Living in London • Local Transportation ACADEMICS • Weather • University of the Arts London • Teaching Style – Important STAYING IN TOUCH Differences • Time Difference • Assessment (Grading) • Computers and Internet • Attendance • Libraries and Academic HOW TO SPEAK BRITISH Support Services ENGLISH • Moodle THINGS TO DO IN LONDON Please see your Pre-Departure Guide - All Programs for additional important pre-departure information. PRE-DEPARTURE Important Phone Numbers ** PROGRAM THESE EMERGENCY NUMBERS INTO YOUR CELL PHONE** ASA Office in Boston, MA University of the Arts London Academic Studies Abroad 272 High Holborn 72 River Park Street London, WC1V 7EY Suite 104 http://www.UAL.ac.uk Needham, MA 02494 Tel: UAL Study Abroad Office: +44 (0) 20 7514 2249 Tel: 617-327-9388 Contact: Aisling Clafferty ([email protected]) 24-hour Emergency Cell: 413-221-4559 Email: [email protected] ASA Site Director Web: www.academicstudies.com Vickie Hyman Email: [email protected] Cell phone: - From the U.S. dial: 011 44 7447 840 064 - In the UK dial: 0 7447 840 064 ** See helpful dialing instructions below. ** U.S. Embassy in London Additional Emergency Numbers http://london.usembassy.gov/ (Local numbers, as dialed in the UK) 24 Grosvenor Square, W1A 1AE Police, Fire, Ambulance: 999 (tube: Bond Street) Campus Emergencies: 2222 Tel: 020 7499 9000 Department of Health: 020 7210 4840 Nightline (a free and confidential service offering support to students): 020 7631 0101 In an emergency, please contact your ASA Site Director immediately. -

Codart Courant 8/June 2004

codart Courant 8/June 2004 codartCourant contents Published by Stichting codart P.O. Box 76709 2 A word from the director Rembrandt, their predecessors and successors: nl-1070 ka Amsterdam 3 News and notes from around the world 16th- to 18th-century Flemish and Dutch The Netherlands 3 Czech Republic, Prague, National drawings in Polish collections www.codart.nl Gallery: A birthday greeting to Hana 26 Krystyna Gutowska-Dudek, The Dutch Seifertová and Flemish paintings from the collection of Managing editor: Rachel Esner 4 France, Paris, Fondation Custodia Jan iiiSobieski housed in Wilanow Palace e [email protected] 4 Hungary, Budapest Museum of Fine Museum Arts 30 Wanda M. Rudzin´ska, The Tilman van Editors: Wietske Donkersloot, 6 Russia, St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Gameren archive in the print room of Gary Schwartz Museum Warsaw University Library t +31 (0)20 305 4515 7 codart zeven: Dutch and Flemish art 33 Study trip to Gdan´sk, Warsaw and f +31 (0)20 305 4500 in Poland Kraków, 18-25 April 2004 e [email protected] 8 Congress, Utrecht, 7-9 March 2004 39 Rulers of Poland, 14th-18th century 13 Antoni Ziemba, The Low Countries and 39 Index of Polish individuals and families codart board Poland: a history of artistic connections 40 Website news Henk van der Walle, chairman 16 Hanna Benesz, Early Netherlandish, 41 Appointments Wim Jacobs, controller of the Instituut Dutch and Flemish paintings in Polish 41 codartmembership news Collectie Nederland, secretary- collections 42 Museum list treasurer 19 Joanna Tomicka, Dutch and Flemish prints 48 codartdates Rudi Ekkart, director of the Rijksbureau in major Polish collections Preview of upcoming exhibitions and other voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie 23 Maciej Monkiewicz, Rubens and events, June-December 2004 Jan Houwert, chairman of the Board of Management of the Koninklijke Wegener N.V. -

Love Letters and the Romantic Novel During the Napoleonic Wars

Love Letters and the Romantic Novel during the Napoleonic Wars Love Letters and the Romantic Novel during the Napoleonic Wars By Sharon Worley Love Letters and the Romantic Novel during the Napoleonic Wars By Sharon Worley This book first published 2016 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2016 by Sharon Worley All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-0127-5 ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-0127-0 TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations .................................................................................... vii Preface ........................................................................................................ ix Diana Reid Haig Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One ............................................................................................... 15 Gender Role Models in Marriage, Romance and Revolution: Staël’s Delphine and Zulma Chapter Two .............................................................................................. 53 The Politics of Love and Gender in the Romantic Novel: Staël’s Corinne -

Chapter One: Introduction and Literature Review 1

PICTURES FOR THE NATION: Conceptualizing a Collection of 'Old Masters' for London 1775-1800 by Kristin Erin Campbell A thesis submitted to the Department of Art In conformity with the requirements for The degree of Doctor of Philosophy Queen’s University Kingston, Ontario, Canada January 2009 Copyright © Kristin Campbell, 2009 Abstract This thesis addresses the growing impulse towards establishing a public, national collection of Old Master pictures for Britain, located in London, in the last quarter of the eighteenth-century. It does so by identifying the importance of individual conceptualizations of what such a collection might mean for a nation, and how it might come to be realized for an imprecisely defined public. My thesis examines the shifting dynamics between private and public collections during the period of 1775 to 1800, repositioning notions of what constituted space for viewing and accessing art in a national context, and investigates just who participated in the ensuing dialogues about various uses of art for the nation. To this end, three case studies have been employed. The first examines the collection of pictures assembled by Sir Robert Walpole and their public legacy. The second explores the proposal for a national collection of art put forth by art dealer Noel Desenfans. The third examines the frustrated plans of Sir Joshua Reynolds for his collection of Old Master pictures. Through the respective lenses provided by the case studies, it is demonstrated that the envisioning of a national gallery for Britain pitched competing perspectives against each other, as different kinds of people jockeyed for cultural authority. The process of articulating and shaping these ambitions with an eye towards national benefit was only beginning to be explored, and negotiations of private ambitions and interests surrounding picture collections for the public was further complicated by factors of social class and profession. -

Museums Going Global

Museums Going Global International museum expansion as a tool of soft power for western universalism Demi Falkmann S1403168 [email protected] Thesis supervisor: Dr. M.H.E. Hoijtink Second reader: Dr. M. Keblusek Faculty of Humanities of Leiden University MA Arts and Culture: Museums and Collections 2018 – 2019 Table of contents Introduction 1 Chapter 1. The globalization of the art market & museums 5 1.1 Museums and the art market 5 1.2 The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation 7 1.3 The State Hermitage Museum 10 1.4 Musée du Louvre 13 1.5 Concluding remarks 15 Chapter 2. International dynamics 18 2.1 Introduction 18 2.2 The Guggenheim and Bilbao 19 2.3 Saint Petersburg and Amsterdam 23 2.4 France and the Emirates 26 2.5 Concluding remarks 28 Chapter 3. Collections, contents and developments 30 3.1 Introduction 30 3.2 The Guggenheim 32 3.3 The Hermitage 36 3.4 The Louvre 38 3.5 Concluding remarks 40 Conclusion 43 Illustrations 46 Credits illustrations 48 Bibliography 49 Literature 49 Web sources 56 Introduction The International Council of Museums (ICOM) is in need of a new museum definition. The current definition of a museum that was made in 2007 is: “A museum is a non-profit, permanent institution in the service of society and its development open to the public, which acquires, conserves, researches, communicates and exhibits the tangible and intangible heritage of humanity and its environment for the purposes of education, study and enjoyment.”1 ICOM is trying to come up with a new definition and are inviting people to submit a proposal.2 This shows that the museum as an institution is constantly subject to change from within as well as from the outside world. -

Byzantine Exhibitions in the State Hermitage Museum, 1861-2006

AN IMPERIAL EYE TO THE PAST: BYZANTINE EXHIBITIONS IN THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM, 1861-2006 Yuri Pyatnitsky The Communist regime and the mental construct of its ideology have been crushed in Russia, as we all know, but the dictum by Vladimir Lenin, the communist leader and idol, that “an individual cannot live in society and be free from society” remains absolutely valid. The idea that “art is for art’s sake” and that “Museums exist only for pure art” is only a romantic dream of some individu- als, not a reality. Admittedly, society’s readiness to respond to artistic traditions, the State and its political aspirations, as well as individual ambi- tions, each have profound infl uences on a muse- um’s life, especially so on its exhibiting activity. Meanwhile, the success of an exhibition gives an impulse for new acquisitions, for new study and, usually, renders the subject matter of the exhibits more popular and fashionable. The best example to illustrate this point is the infl uence exerted by the very successful recent exhibitions held in the Metropolitan Museum of Fig. 1. Piotr Ivanovich Sevastianov (1811-1867). Art, namely, “The Glory of Byzantium” in 1997, Lithography by 1859. The State Hermitage museum. and “Byzantium: Faith and Power” in 2004. And these are not the only cases. The same situation twenty years of impeccable service he resigned in can be attested to in the history of the Byzantine 1851 and devoted his efforts entirely to studying exhibitions in the State Hermitage museum, St. and collecting ancient Christian mementoes. His Petersburg, which spans a period from the middle regular journeys across Europe and the Ortho- th st of the 19 to the beginning of the 21 century, and dox East brought him a reputation as an intrepid in which the Imperial ambitions of Russia were traveller. -

*09 354 Glossary

INDEX Museums and galleries featured in this book are indexed in bold upper case. All artists, architects and craftsmen whose works are mentioned are indexed too. There are also subject references (e.g. Porcelain) which take you to the major collections of work in that field. Prominent figures from history are referenced where they are mentioned in connection with museums, artists or artworks. Major works of art are given in italics. Italicised numbers are picture references. Bold numbers are major references. A André, Dietrich Ernst, artist 171 Abbott, Lemuel, artist 176, 179 Andreoli, Giorgio, ceramicist 339 Adam, Robert, architect 13, 174, 268, 329; Andrews, Michael, artist 296 (Kenwood) 145, 146, 148; (Osterley) Angelico, Fra’, artist 202 228–32, 230; (Royal Society of Arts) Angerstein, John Julius 199 256, 258 (Syon) 285–86 Anne of Denmark, Queen 179, 346 Adam, James, architect 145, 146, 230, 256 Anne, Queen 114, 141, 144, 145, 171, Adam, John, architect 256 290, 347 Adam, William, architect 256 Anrep, Boris, mosaicist 200, 292 Adams, Norman, artist 258 Antiquities (Assyrian) 37–38; (Egyptian) Aelst, Pieter Van, tapestry maker 116 34–37, 37, 62, 234, 271, 321; (Greek) African art 41, 45, 125 32, 34, 271; (Roman) 34, 268, 269, 271 Agasse, Jacques-Laurent, artist 128 Antonello da Messina, artist 204 Aitchison, George, architect 156, 157 Appleyard, Fred, artist 246 Aiton, William Townsend, gardener 50 APSLEY HOUSE 12–17, 13 Albermarle, first Duke of (see Monck) Arad, Ron, designer 332 Albert of Saxe-Coburg, Prince 49, 314 Archer, James, -

National Museum Directors' Conference

National Museum Directors’ Conference newsletter Issue 49 October 2005 Welcome to this month’s NMDC newsletter, which contains information on the newly published Guidance for the Care of Human Remains in Museums and a feature on the events taking place at NMDC member institutions for Black History Month 2005. www.nationalmuseums.org.uk NMDC News NMDC Directors’ Away Day The NMDC Directors had their annual away day on 3 October, hosted by Roy Clare in the Queen’s House at the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich. The Conference discussed issues that would be affecting museums over the next few years including the upcoming comprehensive spending review, the review of lottery good causes and London2012. Following the meeting Directors toured the National Maritime Museum's Nelson & Napoleon exhibition. www.nmm.ac.uk Cultural Diversity Working Group David Lammy, Minister for Culture, met NMDC's Cultural Diversity Working Group on 6 October. The group discussed the priorities for cultural diversity work in national museums and galleries with regard to staffing and governance, collections and programmes and audience development. The discussion also touched on the issue of targets and objectives, the Mayor's Commission Report on African and Asian Heritage and the role of DCMS in relation to diversity. Learning & Access The Learning & Access Committee met at the National Portrait Gallery (NPG) on 29 September. Keith Nichol, Head of Museum Education at DCMS, joined the meeting and gave an update on DCMS and DfES museum education policy, including Strategic Commissioning. The Committee also discussed a proposal for research into the evidence of museum learning. -

People and Places

Contents About this guide Heritage Services in Camden & Useful Contacts People & Places : What do we mean by Heritage? Exploring Community Heritage Exploring Family History Exploring Local History Conservation of Buildings and the Historic Environment HERITAGE Archaeology Museums & Galleries Studying the Past in CAMDEN Sources of Funding A guide to heritage activities in Camden Contents About this guide Heritage Services in Camden & Useful Contacts People & Places : What do we mean by Heritage? Exploring Community Heritage Exploring Family History Exploring Local History Conservation of Buildings and the Historic Environment HERITAGE Archaeology Museums & Galleries Studying the Past in CAMDEN Sources of Funding A guide to heritage activities in Camden About This Guide Camden is rich in heritage. The borough has 30 museums, 36 conservation areas and a range of historic buildings and parks. Camden's population represents many diverse communities, each with its own history and culture. The people of Camden, famous and not-so-famous, all have unique and valuable personal histories and many residents have a strong dedication to the study, preservation and promotion of local heritage. Camden Council recognises the importance of heritage to the people who live and work in the borough. Within the Council, a number of teams work in different aspects of the heritage field. This booklet aims to introduce their services to you, and to point you in the direction of other opportunities and sources of help and advice. Left: Industrial heritage in the heart of Camden (Picture credit: Mandy Lee Jandrell) Heritage Services in Camden & Useful Contacts Camden Arts and Tourism Services Camden Local Studies Camden Arts and Tourism Services (CATS) is and Archives Centre the team within Leisure & Community The Local Studies and Archives Centre Services Department responsible for continue to collect, improve, care for, and developing heritage, arts and cultural activity promote access to the documents which are in Camden.