Museums Going Global

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2010 Kröller-Müller Museum Introduction Mission and History Foreword Board of Trustees Mission and Historical Perspective

Annual report 2010 Kröller-Müller Museum Introduction Mission and history Foreword Board of Trustees Mission and historical perspective The Kröller-Müller Museum is a museum for the visual arts in the midst of peace, space and nature. When the museum opened its doors in 1938 its success was based upon the high quality of three factors: visual art, architecture and nature. This combination continues to define its unique character today. It is of essential importance for the museum’s future that we continue to make connections between these three elements. The museum offers visitors the opportunity to come eye-to-eye with works of art and to concentrate on the non-material side of existence. Its paradise-like setting and famous collection offer an escape from the hectic nature of daily life, while its displays and exhibitions promote an awareness of visual art’s importance in modern society. The collection has a history of almost a hundred years. The museum’s founders, Helene and Anton Kröller-Müller, were convinced early on that the collection should have an idealistic purpose and should be accessible to the public. Helene Kröller-Müller, advised by the writer and educator H.P. Bremmer and later by the entrance Kröller-Müller Museum architect and designer Henry van de Velde, cultivated an understanding of the abstract, ‘idealistic’ tendencies of the art of her time by exhibiting historical and contemporary art together. Whereas she emphasised the development of painting, in building a post-war collection, her successors have focussed upon sculpture and three-dimensional works, centred on the sculpture garden. -

The State Hermitage Museum Annual Report 2012

THE STATE HERMITAGE MUSEUM ANNUAL REPORT n 2012 CONTENTS General Editor 4 Year of Village and Garden Mikhail Piotrovsky, General Director of the State Hermitage Museum, 6 State Hermitage Museum. General Information Corresponding Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 16 Awards Full Member of the Russian Academy of Arts, Professor of St. Petersburg State University, 20 Composition of the Hermitage Collection as of 1 January 2013 Doctor of History 40 Exhibitions 86 Restoration and Conservation 121 Publications EDITORIAL BOARD: 135 Electronic Editions and Video Films Mikhail Piotrovsky, 136 Conferences General Director of the State Hermitage Museum 141 Dissertations Georgy Vilinbakhov, 142 Archaeological Expeditions Deputy Director for Research 158 Major Construction and Restoration of the Buildings Svetlana Adaksina, Deputy Director, Chief Curator 170 Structure of Visits to the State Hermitage in 2012 Marina Antipova, 171 Educational Events Deputy Director for Finance and Planning 180 Special Development Programmes Alexey Bogdanov, Deputy Director for Maintenance 188 International Advisory Board of the State Hermitage Museum Vladimir Matveyev, 190 Guests of the Hermitage Deputy Director for Exhibitions and Development 194 Hermitage Friends Organisations Mikhail Novikov, 204 Hermitage Friends’ Club Deputy Director for Construction 206 Financial Statements of the State Hermitage Museum Mariam Dandamayeva, Academic Secretary 208 Principal Patrons and Sponsors of the State Hermitage Museum in 2012 Yelena Zvyagintseva, 210 Staff Members of -

JOURNAL of EURASIAN STUDIES Volume V., Issue 3

July-September 2013 JOURNAL OF EURASIAN STUDIES Volume V., Issue 3. _____________________________________________________________________________________ MURAKEÖZY, Éva Patrícia Peter the Great, an Inspired Tsar Review on the exhibition devoted to Peter the Great (1672–1725) at the Hermitage Amsterdam between 9 March and 13 September 2013 1. Two Pine Trunks Joined with a Bough Grown from One Trunk into the Other, on a Stand. Russia, St Petersburg. First half of the 18th century. Wood (pine); turned. 64.5x99x31.5 cm. Image is used from www.hermitagemusum.org, courtesy of The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. The above object, rather sombre at the first glance (it may evoke the combined images of a guillotine and a coffin in sensitive souls), represents a rare natural phenomenon: the two tree trunks are joined through a bough which grew from one trunk into the other. This piece stood surprisingly unnoticed1 among the items of Peter the Great’s Cabinet of Curiosities but for me it had an obvious symbolic value: the two pine trunks that grew together through a common branch stood for a natural analogue to the growing together of the Russian Empire and the Dutch Republic, through the person of Peter the Great. The strength of the relationship between the Dutch and the Russian nations in the course of the 17th and 18th centuries becomes evident in this brilliant show, as well as the hard-working and stormy character of this Russian emperor who well merits the epithets «great» and «inspired». The exhibition was jointly 1 It took me quite an effort to get an authorized picture of this object since it is featured neither in the exhibition catalogue nor on the website of the Hermitage Amsterdam. -

201876 L99 CROUWEL BW DEF.Indd

_wim crouwel modernist _wim crouwel modernist Frederike Huygen _Lecturis Publishers CROUWEL_omslag_TEST_23092015.indd 2 15-11-15 13:37 . CROUWEL_omslag_TEST_23092015.indd 2 15-11-15 13:37 _contents 8_preface 154_04 _constructivist: liga, 14 _01 switzerland and ulm _wim crouwel: 170_company printing modish, modern, modernist 176 _05 33_biography in pictures _total design 1963-1972 196_calendars 58_02 _the third dimension 204 _06 112 _signs and elements _the stedelijk museum 118 _03 308_07 _1956-1964: _technology, systems and the van abbe museum patterns and nks 350 148 _circles and spirals _08 _TD 1973-1985: crouwel criticized 378_postage stamps 382_09 _crouwel in the media: a dogmatist full of contradictions 392_10 _museum director, design commissioner and museum designer 410_11 _comeback and revival 433_texts by crouwel 438_cv crouwel 441_bibliography and sources 456_index a graphic designer, but at the same time he is an _preface interdisciplinary designer, a member of a team, and active in and for the whole of our culture. _This book is – naturally enough – based on the earlier book in Dutch, Wim Crouwel, mode en module (1997), of which Hugues Boekraad and I were the authors. It is, however, a different book. Not only has Crouwel done a lot more work since 1997, but new insights about and further research into the profession have led to new texts and chapters. Thus the book now contains the first account of the genesis and development This book is a monographic study of a designer: of the famous New Alphabet and there is exten- Wim Crouwel. The primary object is to give a sive examination of Crouwel’s sources, examples broad picture of his work and activities. -

'Curiously Enchased' Goldsmiths & Diplomats in Baroque Europe

‘Curiously Enchased’ Goldsmiths & Diplomats in Baroque Europe Philippa Glanville FSA. Noted writer and social histororian within the field of the Decorative Arts 17 n 1557 Mary I, Queen of England, instructed Thomas Randolph Figure 1. Silvergilt bottles, London 1579–80. Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg/A.Hagemann her ambassador to Ivan the Terrible as to how to present her gifts; the highlight was a “rich standing cup containing a great Inumber of pieces of plate artificially wrought…you shall rec- with significance beyond their actual form, they had travelled to ommend it for the Rarity of the fashion, assuring him that We do Brandenburg after a failed marriage negotiation with King James I, send it him rather for the newness of the devise than for the value, almost certainly presented to the returning German ambassador. it being the first that was made in these parts in that manner“. (figure 1).1 The Queen’s instructions sum up the essence of gift-exchange Presenting beautiful, costly and preferably rare objects has in early modern statecraft. Emphasized for their novelty and excep- always been central to diplomacy, alongside lavish hospitality. tional workmanship, objects fashioned in gold and silver lay at the Both were public acts, played out before an audience. When mon- heart of these exchanges, since they perfectly combined the finest archs conducted diplomacy personally, an exchange of presents craftsmanship with a recognised expression of value, as indeed helped to cement alliances; prized for their prestige, such gifts they still do. A young enameller Fiona Rae, who received the Royal were widely displayed and publicised through the reports which Warrant in 2001, makes silver boxes with the Prince of Wales’s diplomats sent home. -

The State Hermitage Museum Annual Report 2010 the State Hermitage Museum Annual Report 2010 Contents

The STaTe hermiTage muSeum annual reporT 2010 The STaTe hermiTage muSeum annual reporT 2010 conTenTS General Editor a year of two staircases ............................................................. 4 Mikhail Piotrovsky, Director of the state Hermitage Museum, The State Hermitage Museum. General Information ............... 6 Corresponding Member of the Russian academy of sciences, Full Member of the Russian academy of arts, Awards .......................................................................................... 12 Professor of st. Petersburg state University, Doctor of sciences (History) Composition of the Hermitage Collections as of 1 January 2011 .................................................................... 14 ediTorial Board: Permanent Exhibitions ............................................................... 27 Mikhail Piotrovsky, temporary Exhibitions ............................................................... 30 Director of the state Hermitage Museum Georgy Vilinbakhov, Restoration and Conservation .................................................... 70 Deputy Director for Research Publications ................................................................................. 85 Svetlana Adaksina, Conferences ................................................................................. 96 Deputy Director, Chief Curator Marina Antipova, Dissertations ................................................................................ 99 Deputy Director for Finance and Planning Archaeological Expeditions ...................................................... -

The Hermitage Amsterdam

The Hermitage Amsterdam Information Accreditation Accreditation is requested by the NVK and NIP. Information Liesbeth Osterop, Communication & Public Relations Emma Children’s Hospital AMC Meibergdreef 9, Postbus 22660, 1100 DD Amsterdam Tel. + 31 20 – 566 7987 / [email protected] www.amc.nl/ekz The Dutch Neonatal Follow-Up Work Group celebrates her 20th anniversary by organising an exquisite congress on obstetric, neonatal, and long-term aspects of preterm birth. The last 20 years have shown a decrease in perinatal mortality and neonatal mortality. This improvement has led to treatment of more immature infants with lower birth weights. Evaluating perinatal and neonatal care is therefore more and more important. Although major improvements have been made to optimize preterm children's outcomes at the long-term, preterm birth is still associated with neurodevelopmental disabilities. In the morning, lectures to be given will point out the importance of long-term follow- up for obstetric care, the impact of neonatal care on long-term follow-up, important neurobehavioural interventions as well as the current state of the art on long-term outcomes of NICU graduates. In the afternoon, diverse interactive workshops offer the opportunity to increase knowledge and skills on developmental and school age assessments as well as on intervention programs designed to protect the preterm infant's brain at the neonatal ward or post discharge. Aleid van Wassenaer-Leemhuis, MD, PhD (president) Corine Koopman-Esseboom, MD, PhD Jeroen Vermeulen, MD, PhD Ria Nijhuis-van der Sanden, PPT, PhD Anneloes van Baar, PhD Nynke Weisglas-Kuperus, MD, PhD Cornelieke Aarnoudse-Moens, PhD Programme 9.00 - 9.30 hr Registration Chair: Arend Bos 9.30 - 9.45 hr ‘On 20 years follow up of very low birthweight infants in the Netherlands’ Aleid van Wassenaer-Leemhuis 9.45 - 10.25 hr ‘On the importance of child follow up in decision making in obstetrical care of high risk pregnancies’ Dwight Rouse 10.25 - 11.05 hr ‘How neonatal care has altered long term child outcome. -

Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese, 135 Stranger’S Galleries, 114 Ye Olde Watling, 194 Summerill & Bishop, 169 Young Vic, 179–180

11_037407 bindex.qxp 10/13/06 3:45 PM Page 199 Index See also Accommodations and Restaurant indexes below. GENERAL INDEX Boots the Chemist, 161 Abbey Treasure Museum, 128–129 Bow Wine Vaults, 188–189 ACAVA, 160 British Airways London Eye, 152 Accessorize, 167 British Library, 136–137 Accommodations, 41–69 British Museum, 108–109 Admiral Duncan, 196 Buckingham Palace, 112–113 Ain’t Nothing But Blues Bar, 183 The Bull & Gate, 185 Airlines and airports, 12–15 Bull’s Head, 183 Alfie’s Antique Market, 159 Burberry, 164 Almeida Theatre, 179 Burlington Arcade, 155–156 American Bar, 195 Buses, 33 Anchor, 189 Annie’s Vintage Clothes, 169 Antiques, 159–160 Cabinet War Rooms, 131–132 Apple Market, 172 Cadogan Hall, 177 Apsley House, 135 Calendar of events, 6–10 Arnolfini Portrait, 117 Canary Wharf, 22, 77–78 The Ascot Festival, 10 Candy Bar, 197 Asprey & Garrard, 170 Cantaloupe, 195 ATMs, 4–5 Carlyle’s House, 134 Austin Reed, 164 Carnaby Street, 166 Cecil Sharpe House, 183–184 Ceremony of the Keys, 125 Banqueting House, 130 Changing of the Guard, 112–113, 132 Barbican Centre, 180 Chelsea, 29–30, 60, 101–102 Barbican Theatre, 177 Chelsea Antiques Fair, 9 Barcode, 196 Chelsea Flower Show, 7 Bar Rumba, 186 Children’s Book Centre, 162 Bars and cocktail lounges, 195–196 Churches and cathedrals, 129–130 Bayswater Road, 173 Churchill Museum, 131–132 Beauchamp Tower, 123 Cittie of Yorke, 189 Beau Monde, 164 The City, 17, 18–19, 70–75 Belgravia, 28–29, 59–60 City Hall, 132 Belinda Robertson, 163 Clarence House, 113 Benjamin Franklin House, 131 Classical music, -

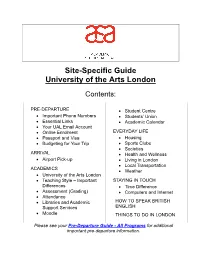

Site-Specific Guide University of the Arts London

Site-Specific Guide University of the Arts London Contents: PRE-DEPARTURE • Student Centre • Important Phone Numbers • Students’ Union • Essential Links • Academic Calendar • Your UAL Email Account • Online Enrolment EVERYDAY LIFE • Passport and Visa • Housing • Budgeting for Your Trip • Sports Clubs • Societies ARRIVAL • Health and Wellness • Airport Pick-up • Living in London • Local Transportation ACADEMICS • Weather • University of the Arts London • Teaching Style – Important STAYING IN TOUCH Differences • Time Difference • Assessment (Grading) • Computers and Internet • Attendance • Libraries and Academic HOW TO SPEAK BRITISH Support Services ENGLISH • Moodle THINGS TO DO IN LONDON Please see your Pre-Departure Guide - All Programs for additional important pre-departure information. PRE-DEPARTURE Important Phone Numbers ** PROGRAM THESE EMERGENCY NUMBERS INTO YOUR CELL PHONE** ASA Office in Boston, MA University of the Arts London Academic Studies Abroad 272 High Holborn 72 River Park Street London, WC1V 7EY Suite 104 http://www.UAL.ac.uk Needham, MA 02494 Tel: UAL Study Abroad Office: +44 (0) 20 7514 2249 Tel: 617-327-9388 Contact: Aisling Clafferty ([email protected]) 24-hour Emergency Cell: 413-221-4559 Email: [email protected] ASA Site Director Web: www.academicstudies.com Vickie Hyman Email: [email protected] Cell phone: - From the U.S. dial: 011 44 7447 840 064 - In the UK dial: 0 7447 840 064 ** See helpful dialing instructions below. ** U.S. Embassy in London Additional Emergency Numbers http://london.usembassy.gov/ (Local numbers, as dialed in the UK) 24 Grosvenor Square, W1A 1AE Police, Fire, Ambulance: 999 (tube: Bond Street) Campus Emergencies: 2222 Tel: 020 7499 9000 Department of Health: 020 7210 4840 Nightline (a free and confidential service offering support to students): 020 7631 0101 In an emergency, please contact your ASA Site Director immediately. -

Portrait of a Gentleman with a Tall Hat and Gloves C

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Rembrandt van Rijn Dutch, 1606 - 1669 Portrait of a Gentleman with a Tall Hat and Gloves c. 1656/1658 oil on canvas transferred to canvas overall: 99.5 × 82.5 cm (39 3/16 × 32 1/2 in.) framed: 132.08 × 114.94 × 13.97 cm (52 × 45 1/4 × 5 1/2 in.) Widener Collection 1942.9.67 ENTRY The early history of Portrait of a Gentleman with a Tall Hat and Gloves and Portrait of a Lady with an Ostrich-Feather Fan [fig. 1] is shrouded in mystery, although it seems likely that they were the pair of portraits by Rembrandt listed in the Gerard Hoet sale in The Hague in 1760. [1] They had entered the Yusupov collection by 1803, when the German traveler Heinrich von Reimers saw them during his visit to the family’s palace in Saint Petersburg, then located on the Fontanka River. [2] Prince Nicolai Borisovich Yusupov (1751–1831) acquired the core of this collection on three extended trips to Europe during the late eighteenth century. In 1827 he commissioned an unpublished five-volume catalog of the paintings, sculptures, and other treasures (still in the family archives at the Arkhangelskoye State Museum & Estate outside Moscow) that included a description as well as a pen-and-ink sketch of each object. The portraits hung in the “Salon des Antiques.” His only son and heir, Prince Boris Nicolaievich Yusupov (1794–1849), published a catalog of the collection in French in 1839. -

PB VGM UK 1 Sept 2015

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Amsterdam, 1 September 2015 Eye-catching entrance hall Van Gogh Museum delivered on time and on budget New entrance building (photo Luuk Kramer) Central hall (photos Ronald Tilleman) Amsterdam’s Van Gogh Museum has a new entrance on Museumplein, Following in the steps oF its neighbouring Rijksmuseum and Stedelijk Museum. For the new entrance building, Kisho Kurokawa Architect & Associates made a sketch that was further developed, materialized, and realized in a record speed of 18 months by Hans van Heeswijk Architects. This Amsterdam based architecture Firm had earlier completed Museum Hermitage Amsterdam, the Royal Picture Gallery Mauritshuis and Museum MORE on schedule and within budget. Van Gogh Museum: one of the Netherlands’ most popular museums The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam is one of the Netherlands’ most popular museums. The ever-growing stream of visitors required intelligent solutions for these buildings, which were designed by Rietveld (1973) and Kurokawa (1999). The design consists in broad outlines of a further elaboration of the elliptical wing of the building that Kurokawa had built in Amsterdam in 1999. Kisho Kurokawa Architect and Associates, the firm founded by the late Kisho Kurokawa and designer of the temporary exhibitions wing opened in 1999, prepared the draft design for the new entrance hall. Hans van Heeswijk Architects then elaborated on this to create a solution in which the existing wing and the new structure form a surprising new whole. “Work to move our main entrance to Museumplein has gone very well,” says museum director Axel Rüger. “It has been delivered within the tight eighteen-month deadline, and on budget. -

Codart Courant 8/June 2004

codart Courant 8/June 2004 codartCourant contents Published by Stichting codart P.O. Box 76709 2 A word from the director Rembrandt, their predecessors and successors: nl-1070 ka Amsterdam 3 News and notes from around the world 16th- to 18th-century Flemish and Dutch The Netherlands 3 Czech Republic, Prague, National drawings in Polish collections www.codart.nl Gallery: A birthday greeting to Hana 26 Krystyna Gutowska-Dudek, The Dutch Seifertová and Flemish paintings from the collection of Managing editor: Rachel Esner 4 France, Paris, Fondation Custodia Jan iiiSobieski housed in Wilanow Palace e [email protected] 4 Hungary, Budapest Museum of Fine Museum Arts 30 Wanda M. Rudzin´ska, The Tilman van Editors: Wietske Donkersloot, 6 Russia, St. Petersburg, State Hermitage Gameren archive in the print room of Gary Schwartz Museum Warsaw University Library t +31 (0)20 305 4515 7 codart zeven: Dutch and Flemish art 33 Study trip to Gdan´sk, Warsaw and f +31 (0)20 305 4500 in Poland Kraków, 18-25 April 2004 e [email protected] 8 Congress, Utrecht, 7-9 March 2004 39 Rulers of Poland, 14th-18th century 13 Antoni Ziemba, The Low Countries and 39 Index of Polish individuals and families codart board Poland: a history of artistic connections 40 Website news Henk van der Walle, chairman 16 Hanna Benesz, Early Netherlandish, 41 Appointments Wim Jacobs, controller of the Instituut Dutch and Flemish paintings in Polish 41 codartmembership news Collectie Nederland, secretary- collections 42 Museum list treasurer 19 Joanna Tomicka, Dutch and Flemish prints 48 codartdates Rudi Ekkart, director of the Rijksbureau in major Polish collections Preview of upcoming exhibitions and other voor Kunsthistorische Documentatie 23 Maciej Monkiewicz, Rubens and events, June-December 2004 Jan Houwert, chairman of the Board of Management of the Koninklijke Wegener N.V.