Communal (1970)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shabbat Hagadol Drasha 2008 Cong

WHAT TIME IS IT? HOW SHOULD I KNOW? Presented By: Rabbi Boaz Tomsky April 12, 2008 Outline 1. Playing mind games. wz erp vmnu .nj ,ufkv o"cnr 2. Forced into a Promotion? ws erp ,una 3. First impressions. wch erp ,una 4. Moshe didn’t get it...I don’t get it.oa vnhn, vru,u oa h"ar 5. In the midnight hour...or pretty close to it /s-:d ;s ,ufrc ,fxn hkcc sunk, 6. But wasn’t Moshe batting a thousand***? 7. Does midnight exist? R’ Zweig 8. Can this rashi help the peace process? wt euxp wt erp ,hatrc h"ar 9. It’s for us. xuruehptu gar 10. It’s like pulling teeth with this kid! 11. Review the 4 Questions. (Ours) 12. At $18 a pound, it’s bound to make you poor. 13. The true origin of fast food*** (see attachment)! ."car 14. Three matzot so 2 more answers. jxp jcz and Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik 15. This night is all about time. h¦n 16. Answering some of the original Q’s...finally! 17. Oh, I just can’t wait to be king! oa ohruyv kgcu wch erp ,una rpx ubrupx 18. The essence of freedom is... Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik 19. A detail or two about the Karbon Pesach. ch erp ,una 20. Why we eat flat bread tonight...it’s in there! jxp ka vsdv 20. Moving right along. oa trzg ictu wth euxp wch erp ,una ejmh ,usku, 22. Matzo vs. Chametz...Matzo wins flat out! 23. What is Chipazon? t"cyhrk jxp ka vsdvu /y ;s ,ufrc ,fxn 24. -

Personal Growth in Judaism I

PERSONAL GROWTH IN JUDAISM I Scaling the Internal Alps f asked to list the concepts with which Judaism is normally associated, we might Isuggest Sabbath observance, dietary restrictions, the Land of Israel, circumcision, and a variety of other ideals and mitzvot specific to the Jewish eligion.r There is, however, a concept that is common to many peoples and cultures which occupies a central place in Judaism: personal growth. Judaism’s comprehensive and unique approach to personal growth is grounded in a Divine mandate to strive to perfect one’s character. There are two Morasha classes that explore the Jewish approach to personal growth. This first class will discuss the centrality of personal growth in Judaism and explore the nature of the “personal growth” that the Torah calls for human beings to attain. The second class will explore the practical side of personal growth: how to pursue it and how to attain it. How does personal development and growth, embraced by many societies, play a central role in Judaism? What is unique about the Jewish approach to personal growth? In which areas is a person expected to achieve personal growth? Who is the ultimate role model to guide our personal growth? What is the ideal to strive for in our personal growth and development? 1 Personal Growth & Development PERSONAL GROWTH IN JUDAISM I Class Outline: Introduction. Scaling the Internal Alps Section I. The Centrality of Personal Growth in Judaism Section II. The Uniqueness of the Jewish Approach to Personal Growth Part A. Character Development and Personal Ethics are Divinely Based Part B. -

Jewish Institute of Religion Rhea Hirsch School of Education Spring 2018

SARAH ROSENBAUM JONES HEBREW UNION COLLEGE- JEWISH INSTITUTE OF RELIGION RHEA HIRSCH SCHOOL OF EDUCATION SPRING 2018 2 Table of Contents Educational Rationale………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Letter to the Educator…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………..6 Scope & Sequence………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………….…….9 Unit 1: Introduction to Middot ……………………………………………………………………………………….……….……………10 Lesson 1:1: What are Middot? …………………………………………………………………………….……………….……11 Lesson 1:2: Me, You, God, and Middot………………………………………………………………………….……………22 Unit 2: Bayn Adam L’Atzmi, Between One and Oneself………………………………………………………….………..……33 Lesson 2:1: Introduction to Middot Bayn Adam L’Atzmi…………………………………..………………………..………34 Lesson 2:2: Anavah (Humility)……………………………………………………………………… ……………….……….…43 Lesson 2:3: Hakarat HaTov (Gratitude) …………………………………………………………………….……………….52 Lesson 2:4: Briyut (Wellness of body, mind, and soul) ………………………………………………………………60 Lesson 2:5: Teshuvah (Repentance) ………………………………………………………………………………………….66 Lesson 2:6: Storybook Work Day……………………………………………………………………………………………….75 Unit 3: Bayn Adam L’Chavero, Between People (Scripted Unit)………………..………………………..…………………77 Lesson 3:1: Introduction to Middot Bayn Adam L’Chavero……………………………………………..………………79 Lesson 3:2: Chesed (Loving Kindness) …….………………………………………………………………………….…………91 Lesson 3:3: Achrayut (Responsibility) ………………………………………………………………………………………..104 Lesson 3:4: Savlanut (Patience) ………………………………………………………………………………….………..……121 Lesson 3:5: Tzedek (Justice) ………………………………………………………………………………………...……………132 -

ANGER in JUDAISM by Rabbi Dr

ANGER IN JUDAISM by Rabbi Dr. Nachum Amsel July 23, 2018 This essay is reprinted from the book, “The Encyclopedia of Jewish Values” published by Urim, or the upcoming books, “The Encyclopedia of Jewish Values: Man to Man” or “The Encyclopedia of Jewish Values: Man to G-d” to be published in the future. This essay is not intended as a source of practical halachic (legal) rulings. For matters of halachah, please consult a qualified posek (rabbi). Although anger is a universal human emotion, it is nevertheless a very unusual sensation and reaction to something that upsets us. There are many variables involved when people get angry, including how angry they get or how long they stay angry after experiencing a threatening, hurtful, or unexpected situation.The definition of anger is “a strong feeling of displeasure and belligerence aroused by a wrong.” It is an emotion related to one's psychological interpretation of having been offended, wronged or denied something that was expected, and it is characterized by a tendency to react through retaliation. Anger as a normal emotion involves a strong uncomfortable and emotional response to a perceived provocation. The external expression of anger can be found in facial expressions, body language, physiological responses, and at times in acts of aggression. Anger is unusual in that some people can control it while others cannot, and everyone expresses his or her anger differently. Sometimes it seems that anger only makes things worse. So why do people get angry? How much control over this emotion do we really have? Why do reactions vary so widely between people or even day to day within the same person? What are the benefits and drawbacks of expressing ourselves and being or getting angry? We will attempt to address some of these questions as we discover the Jewish attitude towards anger through the traditional sources, since the Torah and rabbis have much to say about anger. -

124900176.Pdf

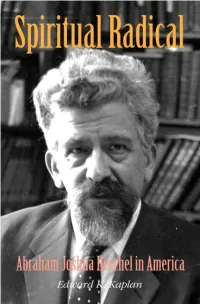

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

L:Ir9111, NORTH AMERICA: 866·550·4EYE, GREAT BRITAIN: 0800 1700 EYE [email protected]

WITHIN ISRAEL:ir9111, NORTH AMERICA: 866·550·4EYE, GREAT BRITAIN: 0800 1700 EYE WWW.EYESQUAD.ORG; [email protected] I . -------- ·-·- ---------------- ~ -------- ------------------- -------- --- ---------- ------- --·-=l ··· . h IN THIS ISSUE ewts•. LETTER FROM JERUSALEM 6 UNiTY Is Nor ON THE HoR1zoN, /BSEl{VER Yonoson Rosenb!urn THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021-6615 IS PllBl.lSHED 10 NE!THER HEKHSHE.R, NOR TZEDEK, _\IO"ITHLY, EXCEPT JU!.Y & Al!GL'Sl Rabbi Avi Shafran Ai'iD A COMIHNl':fl !SSliE FOi~ J..\"IU.\JniFEllRUi\RY. BY THE AGPOATH ISRAf;L OF .l\MERIC..\. 42 BHO ..\!lWAY. :'JEW YonK. NY iooo4. ELUL: PREPARING FOR A NEW START PERIOOlCAl.S POSTAGE PAID IN Nt\V YORK, NY. SliBSCRll'TJON S25.00/Y~.All; 14 STAYING ON TRACK IN TURBULENT TtMES, 2 YL\RS. 548.oo::; YEARS, $69.00. 0l 1TS1DE OF THE UNITED STATES (L'S Rabbi Aaron Brafrnan fll"IOS DRA\VN ON ."i US B."-NK ON!.Y) S!$.OO ~URCllARGE Pl'll Yb\R. SINGl.r NEVER AGAIN AGAll'l, COPY S:;.so: Otr!SJOf: NY •\llEA $3,95; 18 FOllHG:-1 54.50. 1Vafta!i Versch/eisser POSTMASTER: SF"'D ADDRESS CHANGES TO! 21 FROM BE.4R STEARNS TO BAVA METZ/A, TEL 212-797-9000, FAX 646-254-1600 PRlNTt·:o JN THE USA f.!..ndrevv .f\Jeff RABBI NlSSON Wotrri'i. Editor 26 FROM KoLLEL ro THE WoRKPLt,cE, f-.'ditoria/ floord Yos1 l~eber RAUB! JOSEPH f:1.1As, Omirmrm RABI\! ABBA BHliDN) Jos1·:PH Fn1t·:DENSON 29 SHOFAROS: ARE THEY ALL THE Sr\ME? RABBI YISl~Ol-:l. M1,:l11 i<IRZNER 1 R.•\lllH NOSSON Sct!UtMA"i Rabhi Ari Z. -

Ruth W. Messinger to Speak in Ann Arbor March 31

March 2009 Adar/Nisan 5769 Volume XXXIII: Number 6 FREE JCC “Raise the Roof” Auction Ruth W. Messinger to speak in Ann Arbor March 31 Leslie Bash, special to the WJN Elliot Sorkin, special to the WJN The Jewish Community Center of Wash- n Tuesday, March 31, at 7:30 p.m. The American Jewish World Service tenaw County’s 2009 Gala Auction will be Ruth Messinger, president of Amer- (AJWS), is an international development orga- held on Saturday, March 28, at 7 p.m. at the O ican Jewish World Service and one nization providing support to more than 400 JCC. The event will raise funds to replace of the most dynamic speakers in America grassroots social change projects throughout and better insulate the JCC’s roof. There will today, will present “Jews as Global Citizens: the world. Messinger assumed the presidency be a raffle and both live and silent auctions at Our Responsibility in the World.” Speaking of in 1998, following a 20-year career in pub- the event, as well as a “build your own dinner her own experiences in the developing world, lic service in New York City. She is an active buffet” catered by Simply Scrumptious, and Messinger will explain how American Jews, member of her synagogue and serves on the live musical entertainment. who enjoy greater affluence and influence boards of several not-for-profit organizations. The money raised will allow the JCC to than ever before, can do their part to allevi- In honor of her tireless work to end the geno- replace its entire roof—some of which is ate poverty, hunger, violence, disease, and op- AN cide in Darfur, Sudan, Messinger received an M more than 40 years old. -

Judaism and Jewish Philosophy 19 Judaism, Jews and Holocaust Theology

Please see the Cover and Contents in the last pages of this e-Book Online Study Materials on JUDAISM AND JEWISH PHILOSOPHY 19 JUDAISM, JEWS AND HOLOCAUST THEOLOGY JUDAISM Judaism is the religion of the Jewish people, based on principles and ethics embodied in the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) and the Talmud. According to Jewish tradition, the history of Judaism begins with the Covenant between God and Abraham (ca. 2000 BCE), the patriarch and progenitor of the Jewish people. Judaism is among the oldest religious traditions still in practice today. Jewish history and doctrines have influenced other religions such as Christianity, Islam and the Bahá’í Faith. While Judaism has seldom, if ever, been monolithic in practice, it has always been monotheistic in theology. It differs from many religions in that central authority is not vested in a person or group, but in sacred texts and traditions. Throughout the ages, Judaism has clung to a number of religious principles, the most important of which is the belief in a single, omniscient, omnipotent, benevolent, transcendent God, who created the universe and continues to govern it. According to traditional Jewish belief, the God who created the world established a covenant with the Israelites, and revealed his laws and commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai in the form of the Torah, and the Jewish people are the descendants of the Israelites. The traditional practice of Judaism revolves around study and the observance of God’s laws and commandments as written in the Torah and expounded in the Talmud. With an estimated 14 million adherents in 2006, Judaism is approximately the world’s eleventh-largest religious group. -

Toward a Renewed Ethic of Jewish Philanthropy

Toward a Renewed Ethic of Jewish Philanthropy EDITED BY Yossi Prager Robert S. Hirt, Series Editor the michael scharf publication trust of the yeshiva university press new york Toward a Renewed Ethic.indb 3 4/12/10 3:25 PM Copyright © 2010 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Orthodox Forum (19th : 2008 : New York, N.Y.) Toward a renewed ethic of Jewish philanthropy / edited by Yossi Prager. p. cm. -- (Orthodox Forum series) Includes index. ISBN 978-1-60280-137-0 1. Charity. 2. Orthodox Judaism. 3. Charity--History. 4. Generosity--Religious aspects--Judaism. 5. Jews--United States--Charities. 6. Jewish law. 7. Jewish ethics. I. Prager, Yossi. II. Title. BJ1286.C5O63 2010 296.3’677--dc22 2010010016 Distributed by KTAV Publishing House, Inc. 930 Newark Avenue Jersey City, NJ 07306 Tel. (201) 963-9524 Fax. (201) 963-0102 www.ktav.com [email protected] Toward a Renewed Ethic.indb 4 4/12/10 3:25 PM Contents Contributors ix Series Editor’s Preface xiii Robert S. Hirt Editor’s Introduction xv Yossi Prager part 1 Sociology and History 1. Philanthropic Behavior of Orthodox Households 3 Jacob B. Ukeles 2. For the Poor and the Stranger: Fundraisers’ Perspectives on 31 Orthodox Philanthropy Margy-Ruth Davis and Perry Davis 3. American Jewish Philanthropy, Direct Giving, and the Unity 53 of the Jewish Community Chaim I. Waxman 4. Public Charity in Medieval Germany: 79 A Preliminary Investigation Judah Galinsky 5. Jewish Philanthropy in Early Modern and Modern Europe: 93 Theory and Practice in Historical Perspective Jay Berkovitz part 2 Orthodoxy and Federations 6. -

Words That Hurt, Words That Heal

Dedication For Shlomo Telushkin of blessed memory, and Bernard “Bernie” Resnick of blessed memory My father and my uncle: two men of golden tongues and golden hearts, whose words healed all who knew them Epigraph An old Jewish teaching compares the tongue to an arrow. “Why not another weapon, a sword, for example?” one rabbi asks. “Because,” he is told, “if a man unsheathes his sword to kill his friend, and his friend pleads with him and begs for mercy, the man may be mollified and return the sword to its scabbard. But an arrow, once it is shot, cannot be returned.” Contents Cover Title Page Dedication Epigraph Part One: The Power of Words to Hurt Introduction: The Twenty-Four-Hour Test Chapter 1: The (Insufficiently Recognized) Power of Words to Hurt Part Two: How We Speak About Others Chapter 2: The Irrevocable Damage Inflicted by Gossip Chapter 3: The Lure of Gossip Chapter 4: Is It Ever Appropriate to Reveal Humiliating or Harmful Information About Another? Chapter 5: Privacy and Public Figures Part Three: How We Speak to Others Chapter 6: Controlling Rage and Anger Chapter 7: Fighting Fairly Chapter 8: How to Criticize and How to Accept Rebuke Chapter 9: Between Parents and Children Chapter 10: The Cost of Public Humiliation Chapter 11: Is Lying Always Wrong? Chapter 12: Not Everything That Is Thought Should Be Said Part Four: The Power of Words to Heal Chapter 13: Words That Heal—and the Single Most Important Thing to Know About Them Part Five: What Do You Do Now? Making These Practices Part of Your Life Chapter 14: Incorporating -

Recommended Acquisitions for the Max M. and Marjorie B

12/31/84 RECOMMENDED ACQUISITIONS FOR THE MAX M. AND MARJORIE B. KAMPELMAN COLLECTION OF JEWISH ETHICS Abrahams, Israel, ed. and tr. HEBREW ETHICAL WILLS (new edition). JPSA, 1976. $10.95 pbk. Agus, Jacob B. THE EVOLUTION OF JEWISH THOUGHT. Reprint of 1959 ed. Ayer Co. $30. Agus, Jacob B. MODERN PHILOSOPHIES OF JUDAISM. Behrman House, 1941. (OP) Association of Orthodox Jewish Scientist. MEDICAL HALACHA FOR EVERYONE. Feldheim, 1982. $9.95. Bahya Ben Joseph ibn Pakuda. BOOK OF DIRECTION TO THE DUTIES OF THE HEART. Mansoor, ed. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press, 1973. $25. Bamberger, Bernard J., ed. STUDIES IN JEWISH LAW, CUSTOM AND FOLKLORE BY JACOB Z . LAUTERBACH. Ktav. 15.00. Belkin, Samuel. IN HIS IMAGE: THE JEWISH PHILOSOPHY OF MANAS EXPRESSED IN RABBINIC TRADITION. Reprint of 1960 ed. Greenwood Press, 1979. $27.50. Berkovits, Eliezer. NOT IN HEAVEN: THE NATURE AND FUNCTION OF HALAKHA. Ktav, 1983. $15. Berman, Louis A. VEGETARIANISM AND THE JEWISH TRADITION. Ktav, 1982. $10.00, $5.95 pbk. Biale, Rachel. WOMEN AND JEWISH LAW: AN EXPLORATION OF WOMEN’S ISSUES IN HALACHIC SOURCES. Schocken, $18.95. Borowitz, Eugene B. CHOICES IN MODERN JEWISH THOUGHT. Behrman House, 1983. $9.95 pbk. Borowitz, Eugene B. LIBERAL JUDAISM. UAHC, 1984. $7.95 pbk. Borowitz, Eugene B. MODERN VARIETIES OF JEWISH THOUGHT. Behrman, 1982. $9.95 pbk. (OP) T Brennan, William. MEDICAL HOLOCAUST I: EXPERMINATIVE MEDICINE IN NAZI GERMANY AND CONTEMPORARY AMERICA. Nordland Pub., 1980. $19.95, $8.95 pbk. Brennan, William. MEDICAL HOLOCAUST II: THE LANGUAGE OF EXTERMINATIVE MEDICINE IN NAZI GERMANY AND CONTEMPORARY AMERICA. Nordland Pub., 1981. -

Elul Enrichment: Qualities

…Torah is acquired with 48 Elul Enrichment: qualities. These are: , listening, Study Aug 12|Elul 1 – Study (Talmud) verbalizing, comprehension of the “Study is greater, for it leads to action.” (TB. Kiddushin 40b) heart, fear, awe, humility, joy, purity, serving the sages, bonding The Israelites heard the 10 commandments at Sinai on the Jewish holiday of Shavuot, but with friends, debating with th students, tranquility, study of text just 40 days later (on the 17 of the Hebrew month of Tammuz) the first set of stone tablets & context, minimizing engagement was smashed as a result of the sin of the golden calf. For another 40 days, Moses returned in business, minimizing superficial to the summit of Sinai pleading successfully with God on Israel’s behalf. With the beginning socialization, minimizing pleasure, of Elul, Moses again ascended for a final 40 days. There he was taught the thirteen minimizing sleep, minimizing talk, attributes of mercy (recited during the traditional Selichot liturgy), and obtained complete minimizing levity, slowness to Kapparah (atonement) for the Jewish people as manifest with the ‘renewal of vows’ anger, good heartedness, trust in embodied in the second set of tablets which Moses returned with on Yom Kippur (10th of the sages, acceptance of Tishrei). Since then, the period between the 1st of Elul and Yom Kippur has been a month of suffering, knowing one's place, Divine mercy and forgiveness. (See Rashi to Exodus 32:1 and 33:11) satisfaction with one's lot, qualifying one's words, not taking credit for oneself, likableness, love The human psyche, however, is one that finds dignity in earned accomplishments, and of God, love of humanity, love of undeserved forgiveness is capable of withering our self-worth.