Judaism and Jewish Philosophy 19 Judaism, Jews and Holocaust Theology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Book of Zohar ((Itemsitems 666-71).6-71)

The Path of Kabbalah By Rav Michael Laitman PhD The Path of Kabbalah LAITMAN KABBALAH PUBLISHERS By Rav Michael Laitman PhD Executive Editor: Benzion Giertz Editor: Claire Gerus Translation: Chaim Ratz Compilation: Shlomi Bohana Layout: Baruch Khovov Laitman Kabbalah Publishers Website: www.kabbalah.info Laitman Kabbalah Publishers E-mail: [email protected] THE PATH OF KABBALAH Copyright © 2005 by MICHAEL LAITMAN. All rights reserved. Published by Laitman Kabbalah Publishers, 1057 Steeles Avenue West, Suite 532, Toronto, ON, M2R 3X1, Canada. Printed in Canada. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. ISBN: 0-9732315-9-9 FIRST EDITION: DECEMBER 2005 The Path of Kabbalah TA B LE OF CONTEN T S Part One: The Beginning .........................................................................9 Part Two: Phases of Spiritual Evolution ............................................... 70 Part Three: The Structure of the Upper Worlds .................................140 Part Four: Proper Study ...................................................................... 253 Part Five: Religion, Prejudice and Kabbalah ...................................... 306 Part Six: Genesis ................................................................................. 320 Part Seven: The Inner Meaning .......................................................... 333 Detailed Table of Contents ............................................................... -

RCVP: Really Cool

1 RCVP: Really Cool and Valuable Person Compiled by Taylor-Paige Guba, RCVP of NFTY Ohio Valley 2016-2017 with help from past RCVPs and NFTY resources Contact info and Social Media Phone: 317-902-8934 Email: [email protected] Twitter: @ov_rcvp Instagram: @gubagirl Facebook: Taylor-Paige Guba Don’t forget to follow NFTY-OV on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram! Join the NFTY-OV Facebook group! 2 And now a rap from DJ goobz… So listen up peeps. I got a couple things I need you to hear, You better be listening with two ears, The path you are walking down today, Is a dope path so make some way, First you got the R and that’s pretty sweet, Religion is tight so be ready to yeet, The C comes next just creepin on in, Culture is swag so let’s begin, The VP part brings it all together, Wrap it all up and you got 4 letters, Word to yo mamma To clarify, I am very excited to work with all of you fabulous people. Our network has complex responsibilities and I have put everything I could think of that would help us all have a great year in this network packet. Here you will find: ● Some basic definitions ● Standard service outlines ● Jewish holiday dates ● A few other fun items 3 So What Even is Reform Judaism? Great question! It is a pluralistic, progressive, egalitarian sect of Judaism that allows the individual autonomy to decide their personal practices and observations based on all Jewish teachings (Torah, Talmud, Halacha, Rabbis etc.) as well as morals, ethics, reason and logic. -

Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon

301 Tehillat Hashem and Other Verses Before Birkat Ha-Mazon By: ZVI RON In this article we investigate the origin and development of saying vari- ous Psalms and selected verses from Psalms before Birkat Ha-Mazon. In particular, we will attempt to explain the practice of some Ashkenazic Jews to add Psalms 145:21, 115:18, 118:1 and 106:2 after Ps. 126 (Shir Ha-Ma‘alot) and before Birkat Ha-Mazon. Psalms 137 and 126 Before Birkat Ha-Mazon The earliest source for reciting Ps. 137 (Al Naharot Bavel) before Birkat Ha-Mazon is found in the list of practices of the Tzfat kabbalist R. Moshe Cordovero (1522–1570). There are different versions of this list, but all versions include the practice of saying Al Naharot Bavel.1 Some versions specifically note that this is to recall the destruction of the Temple,2 some versions state that the Psalm is supposed to be said at the meal, though not specifically right before Birkat Ha-Mazon,3 and some versions state that the Psalm is only said on weekdays, though no alternative Psalm is offered for Shabbat and holidays.4 Although the ex- act provenance of this list is not clear, the parts of it referring to the recitation of Ps. 137 were already popularized by 1577.5 The mystical work Seder Ha-Yom by the 16th century Tzfat kabbalist R. Moshe ben Machir was first published in 1599. He also mentions say- ing Al Naharot Bavel at a meal in order to recall the destruction of the 1 Moshe Hallamish, Kabbalah in Liturgy, Halakhah and Customs (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University Press, 2000), pp. -

Rav Yisroel Abuchatzeira, Baba Sali Zt”L

Issue (# 14) A Tzaddik, or righteous person makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. (Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach; Sefer Bereishis 7:1) Parshas Bo Kedushas Ha'Levi'im THE TEFILLIN OF THE MASTER OF THE WORLD You shall say it is a pesach offering to Hashem, who passed over the houses of the children of Israel... (Shemos 12:27) The holy Berditchever asks the following question in Kedushas Levi: Why is it that we call the yom tov that the Torah designated as “Chag HaMatzos,” the Festival of Unleavened Bread, by the name Pesach? Where does the Torah indicate that we might call this yom tov by the name Pesach? Any time the Torah mentions this yom tov, it is called “Chag HaMatzos.” He answered by explaining that it is written elsewhere, “Ani l’dodi v’dodi li — I am my Beloved’s and my Beloved is mine” (Shir HaShirim 6:3). This teaches that we relate the praises of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, and He in turn praises us. So, too, we don tefillin, which contain the praises of HaKadosh Baruch Hu, and HaKadosh Baruch Hu dons His “tefillin,” in which the praise of Klal Yisrael is written. This will help us understand what is written in the Tanna D’Vei Eliyahu [regarding the praises of Klal Yisrael]. The Midrash there says, “It is a mitzvah to speak the praises of Yisrael, and Hashem Yisbarach gets great nachas and pleasure from this praise.” It seems to me, says the Kedushas Levi, that for this reason it says that it is forbidden to break one’s concentration on one’s tefillin while wearing them, that it is a mitzvah for a man to continuously be occupied with the mitzvah of tefillin. -

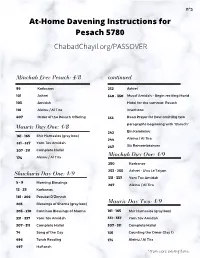

Copy of Copy of Prayers for Pesach Quarantine

ב"ה At-Home Davening Instructions for Pesach 5780 ChabadChayil.org/PASSOVER Minchah Erev Pesach: 4/8 continued 99 Korbanos 232 Ashrei 101 Ashrei 340 - 350 Musaf Amidah - Begin reciting Morid 103 Amidah Hatol for the summer, Pesach 116 Aleinu / Al Tira insertions 407 Order of the Pesach Offering 353 Read Prayer for Dew omitting two paragraphs beginning with "Baruch" Maariv Day One: 4/8 242 Ein Kelokeinu 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 244 Aleinu / Al Tira 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 247 Six Remembrances 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 174 Aleinu / Al Tira Minchah Day One: 4/9 250 Korbanos 253 - 255 Ashrei - U'va Le'Tziyon Shacharis Day One: 4/9 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 267 Aleinu / Al Tira 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) Maariv Day Two: 4/9 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 161 - 165 Shir Hamaalos (gray box) 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 74 Song of the Day 136 Counting the Omer (Day 1) 496 Torah Reading 174 Aleinu / Al Tira 497 Haftorah *From a pre-existing flame Shacharis Day Two: 4/10 Shacharis Day Three: 4/11 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 5 - 9 Morning Blessings 12 - 25 Korbanos 12 - 25 Korbanos 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 181 - 202 Pesukei D'Zimrah 203 Blessings of Shema (gray box) 203 - 210 Blessings of Shema & Shema 205 - 210 Continue Blessings of Shema 211- 217 Shabbos Amidah - add gray box 331 - 337 Yom Tov Amidah pg 214 307 - 311 Complete Hallel 307 - 311 "Half" Hallel - Omit 2 indicated 74 Song of -

Supernal Wisdom

Celestial Grace Temple English Zohar – Supernal Wisdom Zohar Book 7 - Supernal Wisdom: 40. Rabbi Yudai asked, “What does the word BERESHEET mean?” It is the wisdom, upon which the world, ZA, is established to enter the concealed supernal secrets, namely the Light of Bina. Here are the six Supernal and great properties, VAK de Bina, from which everything emerges. The six river mouths, VAK de ZA, that flow into the Great Sea (Malchut) were formed from them. The word BERESHEET consists of the words BARAH (created) and SHEET (Aramaic: six), meaning that six properties were created. Who created them? He who is unmentioned, concealed, and unknown: Arich Anpin. There are two types of Ohr Hochma (Light of Wisdom) in the world of Atzilut: 1. The original Light, Ohr Hochma of AA, called “the concealed Ohr Hochma.” This Light of Hochmais present only in Partzuf AA and does not spread to the lower Partzufim. 2. Ohr Hochma that descends via thirty-two paths from Bina, who ascended to Rosh de AA to receive Ohr Hochma and pass it to ZA. Hence, the word Beresheet means Be-Resheet, with-Hochma. However, this is not the true Ohr Hochma that is concealed in AA, but rather the Light that descends via thirty-two paths from Bina to ZA and sustains ZON. It is written that the world is established on the “concealed supernal secrets.” Copyright © 2014 celestialgrace.org 1 Celestial Grace Temple English Zohar – Supernal Wisdom For when ZON (called “world”) receive the Light of Hochma of thirty- two paths, they ascend to AVI, the concealed supernal secrets. -

Download the Abstracts As

English Abstracts “I Shall Work”: Justifications for and Consequences of Ultra-Orthodox Women Shouldering the Burden of Breadwinning Iris Brown (Hoizman) From the early 1960s, ultra-Orthodox society, and particularly its “Lithuanian” component, gradually adopted a socioeconomic model in which women became the primary providers. Ultra-Orthodox women took upon themselves the financial responsibility for the family, as if to say: “I shall work, sustain, provide, and support.” Yet, in addition, they continued to declare: “I shall educate, deal with the day-to-day running of the house, and take care of my husband.” The entry of the ultra-Orthodox woman into the workplace enabled the “society of learners” to function (i.e. enabled the husbands to dedicate their time exclusively to Torah study), but it also threatened the patriarchal structure of the ultra-Orthodox family. Ultra-Orthodox leadership tried to prevent this undesirable consequence, in essence seeking to set a social revolution into motion without paying the price. In the first generation of the revolution, the process was promoted as “self-sacrifice” for the sake of Torah, combining the desire to aid in the building of the “Torah world” in the Land of Israel and to give honor to the husband-Torah scholar. As the revolution progressed, however, the innovative development demanded justification and defense. This article examines how ultra-Orthodox leaders and educators have dealt with the fundamental difficulties posed by the “woman as provider” paradigm, such as the blurring of masculine and feminine roles and the perceived progressive increase in the status of women versus the sanctified ultra-Orthodox theological principle that posits the inherent decline of progressive generations. -

Kiruv Rechokim

l j J I ' Kiruv Rechokim ~ • The non-professional at work 1 • Absorbing uNew Immigrants" to Judaism • Reaching the Russians in America After the Elections in Israel • Torah Classics in English • Reviews in this issue ... "Kiruv Rechokim": For the Professional Only, Or Can Everyone Be Involved? ................... J The Four-Sided Question, Rabbi Yitzchok Chinn ...... 4 The Amateur's Burden, Rabbi Dovid Gottlieb ......... 7 Diary of a New Student, Marty Hoffman ........... 10 THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN A Plea From a "New Immigrant" to Judaism (a letter) 12 0021-6615) is published monthly, except July and August, by the Reaching the Russians: An Historic Obligation, Agudath Israel of America, 5 Nissan Wolpin............................... 13 Beekman Street, New York, N.Y. 10038. Second class postage paid at New York, N. Y. Subscription After the Elections, Ezriel Toshavi ..................... 19 Sl2.00 per year; two years, S2LOO; three years, S28.00; out Repairing the Effects of Churban, A. Scheinman ........ 23 side of the United States, $13.00 per year. Single copy, $1.50 Torah Classic in English (Reviews) Printed in the U.S.A. Encyclopedia of Torah Thoughts RABBI NissoN Wotr1N ("Kad Hakemach") . 29 Editor Kuzari .......................................... JO Editorial Board Pathways to Eternal Life ("Orchoth Chaim") ....... 31 DR. ERNST BooENHEIMER Chairman The Book of Divine Power ("Gevuroth Hashem") ... 31 RABBI NATHAN BULMAN RABBI JosEPH ELIAS JOSEPH fRIEDENSON Second Looks on the Jewish Scene I RABB! MOSHE SttERER Of Unity and Arrogance ......................... 33 If· MICHAEL RorasCHlLD I Business Manager Postscript TttE JEWISH OBSERVER does not I assume responsibility for the I Kashrus of any product or ser Return of the Maggidim, Chaim Shapiro ........... -

Jewish Subcultures Online: Outreach, Dating, and Marginalized Communities ______

JEWISH SUBCULTURES ONLINE: OUTREACH, DATING, AND MARGINALIZED COMMUNITIES ____________________________________ A Thesis Presented to the Faculty of California State University, Fullerton ____________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in American Studies ____________________________________ By Rachel Sara Schiff Thesis Committee Approval: Professor Leila Zenderland, Chair Professor Terri Snyder, Department of American Studies Professor Carrie Lane, Department of American Studies Spring, 2016 ABSTRACT This thesis explores how Jewish individuals use and create communities online to enrich their Jewish identity. The Internet provides Jews who do not fit within their brick and mortar communities an outlet that gives them voice, power, and sometimes anonymity. They use these websites to balance their Jewish identities and other personal identities that may or may not fit within their local Jewish community. This research was conducted through analyzing a broad range of websites. The first chapter, the introduction, describes the Jewish American population as a whole as well as the history of the Internet. The second chapter, entitled “The Black Hats of the Internet,” discusses how the Orthodox community has used the Internet to create a modern approach to outreach. It focuses in particular on the extensive web materials created by Chabad and Aish Hatorah, which offer surprisingly modern twists on traditional texts. The third chapter is about Jewish online dating. It uses JDate and other secular websites to analyze how Jewish singles are using the Internet. This chapter also suggests that the use of the Internet may have an impact on reducing interfaith marriage. The fourth chapter examines marginalized communities, focusing on the following: Jewrotica; the Jewish LGBT community including those who are “OLGBT” (Orthodox LGBT); Punk Jews; and feminist Jews. -

TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 a Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M

Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary Yeshiva University Center for the Jewish Future THE BENJAMIN AND ROSE BERGER TORAH TO-GO® Established by Rabbi Hyman and Ann Arbesfeld June 2017 • Shavuot 5777 A Special Edition Celebrating President Richard M. Joel WITH SHAVUOT TRIBUTES FROM Rabbi Dr. Kenneth Brander • Rabbi Dr. Hillel Davis • Rabbi Dr. Avery Joel • Dr. Penny Joel Rabbi Dr. Josh Joseph • Rabbi Menachem Penner • Rabbi Dr. Jacob J. Schacter • Rabbi Ezra Schwartz Special Symposium: Perspectives on Conversion Rabbi Eli Belizon • Joshua Blau • Mrs. Leah Nagarpowers • Rabbi Yona Reiss Rabbi Zvi Romm • Mrs. Shoshana Schechter • Rabbi Michoel Zylberman 1 Rabbi Isaac Elchanan Theological Seminary • The Benjamin and Rose Berger CJF Torah To-Go Series • Shavuot 5777 We thank the following synagogues which have pledged to be Pillars of the Torah To-Go® project Beth David Synagogue Green Road Synagogue Young Israel of West Hartford, CT Beachwood, OH Century City Los Angeles, CA Beth Jacob Congregation The Jewish Center Beverly Hills, CA New York, NY Young Israel of Bnai Israel – Ohev Zedek Young Israel Beth El of New Hyde Park New Hyde Park, NY Philadelphia, PA Borough Park Koenig Family Foundation Young Israel of Congregation Brooklyn, NY Ahavas Achim Toco Hills Atlanta, GA Highland Park, NJ Young Israel of Lawrence-Cedarhurst Young Israel of Congregation Cedarhurst, NY Shaarei Tefillah West Hartford West Hartford, CT Newton Centre, MA Richard M. Joel, President and Bravmann Family University Professor, Yeshiva University Rabbi Dr. Kenneth -

Monatsschrift Für Geschichte Und Wissenschaft Des Judenthums

'^i^fiti 100 =00 iOO =o IS ico M^i^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from University of Toronto littp://www.archive.org/details/monatsschriftf59gese Monatsschrift FÜR GESCHICHTE UND WISSENSCHAFT DES JUDENTUMS BEGRÜNDET VON Z. FRANKEL. Organ der Gesellschaft zur Förderung der Wissenschaft des Judentums Herausgegeben von Prof. Dr. M. BRANN. Neunundfünfzigster Jahrgang. NEUE FOLGE, DREIUNDZWANZIGSTEB JAHRGANG. BRESLAU. KOEBNER'SCHE VERLAGSBUCHHANDLUNG. (BARASCH UND RIESENFELD.) 1915. Der jetzige Weltkrieg und die Bibel. Vortrag gehalten in der Wiener »Urania« am g. Januar 1915 von M. Güdemann. I. Nichts wird in der Bibel als so erstrebenswert hingestellt, kein Gut wird mit so warmen, eindringlichen Worten als der Güter höchstes gepriesen, wie der Friede. Der Priestersegen, der in allen Gotteshäusern, welcher Konfession sie dienen mögen, in verehrungsvoller Übung steht, lautet in seiner Kürze und Einfach- heit: »Der Herr segne dich und behüte dich. Der Herr lasse dir sein Antlitz leuchten und sei dir gnädig. Der Herr wende dir sein Antlitz zu und gebe dir Frieden.« Der ganze Satz ist bild- haft, nur ein Gut wird ausdrücklich namhaft gemacht und er- beten: das ist nicht Reichtum, nicht Ehre, Herrschaft, Macht und Größe, sondern dasjenige Gut, um das der Mächtigste, der es nicht besitzt, den Ärmsten beneidet, der es besitzt — der Friede. Wir werden diese hohe Veranschlagung des Friedens heute mehr als je begreifen, weil wir uns in einem Weltkriege, in einem Welt- brande befinden. Denn was heute alle im tiefsten Innern bewegt, was alle Herzen ausfüllt, alle Gemüter beseelt, das läßt sich unter Anwendung und entsprechender Umänderung eines be- kannten Goetheschen Satzes in die Worte zusammenfassen: »Nach Frieden drängt, am Frieden hängt doch alles«. -

NP Distofattend-2014-15

DISTRICT_CD DISTRICT_NAME NONPUB_INST_CD NONPUB_INST_NAME 91‐223‐NP‐HalfK 91‐224‐NP‐FullK‐691‐225‐NP‐7‐12 Total NonPub 010100 ALBANY 010100115665 BLESSED SACRAMENT SCHOOL 0 112 31 143 010100 ALBANY 010100115671 MATER CHRISTI SCHOOL 0 145 40 185 010100 ALBANY 010100115684 ALL SAINTS' CATHOLIC ACADEMY 0 100 29 129 010100 ALBANY 010100115685 ACAD OF HOLY NAME‐LOWER 049049 010100 ALBANY 010100115724 ACAD OF HOLY NAMES‐UPPER 0 18 226 244 010100 ALBANY 010100118044 BISHOP MAGINN HIGH SCHOOL 0 0 139 139 010100 ALBANY 010100208496 MAIMONIDES HEBREW DAY SCHOOL 0 45 22 67 010100 ALBANY 010100996053 HARRIET TUBMAN DEMOCRATIC 0 0 18 18 010100 ALBANY 010100996179 CASTLE ISLAND BILINGUAL MONT 0 4 0 4 010100 ALBANY 010100996428 ALBANY ACADEMIES (THE) 0 230 572 802 010100 ALBANY 010100997616 FREE SCHOOL 0 25 7 32 010100 Total ALBANY 1812 010201 BERNE KNOX 010201805052 HELDERBERG CHRISTIAN SCHOOL 1 25 8 34 010201 Total 0 34 010306 BETHLEHEM 010306115761 ST THOMAS THE APOSTLE SCHOOL 0 148 48 196 010306 BETHLEHEM 010306809859 MT MORIAH ACADEMY 0 11 20 31 010306 BETHLEHEM 010306999575 BETHLEHEM CHILDRENS SCHOOL 1 12 3 16 010306 Total 0 243 010500 COHOES 010500996017 ALBANY MONTESSORI EDUCATION 0202 010500 Total 0 2 010601 SOUTH COLONIE 010601115674 CHRISTIAN BROTHERS ACADEMY 0 38 407 445 010601 SOUTH COLONIE 010601216559 HEBREW ACAD‐CAPITAL DISTRICT 0 63 15 78 010601 SOUTH COLONIE 010601315801 OUR SAVIOR'S LUTHERAN SCHOOL 9 76 11 96 010601 SOUTH COLONIE 010601629639 AN NUR ISLAMIC SCHOOL 0 92 23 115 010601 Total 0 734 010623 NORTH COLONIE CSD 010623115655