S.Kahn.Thesis-Igniting Souls

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shabbat Hagadol Drasha 2008 Cong

WHAT TIME IS IT? HOW SHOULD I KNOW? Presented By: Rabbi Boaz Tomsky April 12, 2008 Outline 1. Playing mind games. wz erp vmnu .nj ,ufkv o"cnr 2. Forced into a Promotion? ws erp ,una 3. First impressions. wch erp ,una 4. Moshe didn’t get it...I don’t get it.oa vnhn, vru,u oa h"ar 5. In the midnight hour...or pretty close to it /s-:d ;s ,ufrc ,fxn hkcc sunk, 6. But wasn’t Moshe batting a thousand***? 7. Does midnight exist? R’ Zweig 8. Can this rashi help the peace process? wt euxp wt erp ,hatrc h"ar 9. It’s for us. xuruehptu gar 10. It’s like pulling teeth with this kid! 11. Review the 4 Questions. (Ours) 12. At $18 a pound, it’s bound to make you poor. 13. The true origin of fast food*** (see attachment)! ."car 14. Three matzot so 2 more answers. jxp jcz and Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik 15. This night is all about time. h¦n 16. Answering some of the original Q’s...finally! 17. Oh, I just can’t wait to be king! oa ohruyv kgcu wch erp ,una rpx ubrupx 18. The essence of freedom is... Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik 19. A detail or two about the Karbon Pesach. ch erp ,una 20. Why we eat flat bread tonight...it’s in there! jxp ka vsdv 20. Moving right along. oa trzg ictu wth euxp wch erp ,una ejmh ,usku, 22. Matzo vs. Chametz...Matzo wins flat out! 23. What is Chipazon? t"cyhrk jxp ka vsdvu /y ;s ,ufrc ,fxn 24. -

Personal Growth in Judaism I

PERSONAL GROWTH IN JUDAISM I Scaling the Internal Alps f asked to list the concepts with which Judaism is normally associated, we might Isuggest Sabbath observance, dietary restrictions, the Land of Israel, circumcision, and a variety of other ideals and mitzvot specific to the Jewish eligion.r There is, however, a concept that is common to many peoples and cultures which occupies a central place in Judaism: personal growth. Judaism’s comprehensive and unique approach to personal growth is grounded in a Divine mandate to strive to perfect one’s character. There are two Morasha classes that explore the Jewish approach to personal growth. This first class will discuss the centrality of personal growth in Judaism and explore the nature of the “personal growth” that the Torah calls for human beings to attain. The second class will explore the practical side of personal growth: how to pursue it and how to attain it. How does personal development and growth, embraced by many societies, play a central role in Judaism? What is unique about the Jewish approach to personal growth? In which areas is a person expected to achieve personal growth? Who is the ultimate role model to guide our personal growth? What is the ideal to strive for in our personal growth and development? 1 Personal Growth & Development PERSONAL GROWTH IN JUDAISM I Class Outline: Introduction. Scaling the Internal Alps Section I. The Centrality of Personal Growth in Judaism Section II. The Uniqueness of the Jewish Approach to Personal Growth Part A. Character Development and Personal Ethics are Divinely Based Part B. -

Jewish Institute of Religion Rhea Hirsch School of Education Spring 2018

SARAH ROSENBAUM JONES HEBREW UNION COLLEGE- JEWISH INSTITUTE OF RELIGION RHEA HIRSCH SCHOOL OF EDUCATION SPRING 2018 2 Table of Contents Educational Rationale………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………3 Letter to the Educator…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………..6 Scope & Sequence………………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………….…….9 Unit 1: Introduction to Middot ……………………………………………………………………………………….……….……………10 Lesson 1:1: What are Middot? …………………………………………………………………………….……………….……11 Lesson 1:2: Me, You, God, and Middot………………………………………………………………………….……………22 Unit 2: Bayn Adam L’Atzmi, Between One and Oneself………………………………………………………….………..……33 Lesson 2:1: Introduction to Middot Bayn Adam L’Atzmi…………………………………..………………………..………34 Lesson 2:2: Anavah (Humility)……………………………………………………………………… ……………….……….…43 Lesson 2:3: Hakarat HaTov (Gratitude) …………………………………………………………………….……………….52 Lesson 2:4: Briyut (Wellness of body, mind, and soul) ………………………………………………………………60 Lesson 2:5: Teshuvah (Repentance) ………………………………………………………………………………………….66 Lesson 2:6: Storybook Work Day……………………………………………………………………………………………….75 Unit 3: Bayn Adam L’Chavero, Between People (Scripted Unit)………………..………………………..…………………77 Lesson 3:1: Introduction to Middot Bayn Adam L’Chavero……………………………………………..………………79 Lesson 3:2: Chesed (Loving Kindness) …….………………………………………………………………………….…………91 Lesson 3:3: Achrayut (Responsibility) ………………………………………………………………………………………..104 Lesson 3:4: Savlanut (Patience) ………………………………………………………………………………….………..……121 Lesson 3:5: Tzedek (Justice) ………………………………………………………………………………………...……………132 -

Interpreting Diagrams from the Sefer Yetsirah and Its Commentaries 1

NOTES 1 Word and Image in Medieval Kabbalah: Interpreting Diagrams from the Sefer Yetsirah and Its Commentaries 1. The most notorious example of these practices is the popularizing work of Aryeh Kaplan. His critical editions of the SY and the Sefer ha Bahir are some of the most widely read in the field because they provide the texts in Hebrew and English with comprehensive and useful appendices. However, these works are deeply problematic because they dehistoricize the tradi- tion by adding later diagrams to earlier works. For example, in his edition of the SY he appends eighteenth-century diagrams to later versions of this tenth-century text. Popularizers of kabbalah such as Michael Berg of the Kabbalah Centre treat the Zohar as a second-century rabbinic tract without acknowledging textual evidence to the contrary. See his introduction to the Centre’s translation of the Zohar: P. S. Berg. The Essential Zohar. New York: Random House, 2002. 2. For a variety of reasons, kabbalistic works were transmitted in manuscript form long after other works, such as the Hebrew Bible, the Talmud, and their commentaries were widely available in print. This is true in large part because kabbalistic treatises were “private” works, transmitted from teacher to student. Kabbalistic manuscripts were also traditionally transmitted in manuscript form because of their provenance. The Maghreb and other parts of North Africa were important centers of later mystical activity, and print technology came quite late to these regions, with manuscript culture persisting well into the nineteenth, and even into the mid- twentieth century in some regions. -

Parasha Meditation Vayetze

בס”ד Parasha Meditation Vayetze Bereishit 28:10-32:3 By Rebbetzin Chana Bracha Siegelbaum Stepping Inwards on the Ladder of Ascent Introduction: וַיַּחֲ �ם וְהִנֵּה סֻלָּם מֻצָּב אַרְ צָה וְרֹאשׁוֹ מַגִּיעַ הַשָּׁמָיְמָה וְהִנֵּה מַלְאֲכֵי אֱ�הִים עֹלִים וְיֹרְ דִים בּוֹ: (בראשית פרק כח, פסוק יב) 1 “He dreamed, and behold a ladder is standing on the earth, but its head reaches heaven…”0F The metaphor of Ya’acov’s ladder lends itself to profound meditation. The ladder symbolizes the connection that links earth to heaven, matter below to spirit Above, and us to G*d. Keeping our Head in Heaven with our Feet on the Ground Netivat Shalom explains that this world is like a ladder standing on the earth, while its head reaches heaven. Through being involved with earthly matters, we can reach the very highest level, until our “head reaches heaven.” We have the opportunity to elevate ourselves and cleave to Hashem, specifically by elevating the earthly lowly matters towards heavenly levels. The Torah verse also teaches us, that even when we are involved in matters of this world, we mustn’t forget to keep our head in heaven. When we really desire to elevate the physical and bring heaven down to earth, then Hashem will watch over us and help us. We learn this from the 2 3 Behold, Hashem was standing over him,”1F – to guard him.2F“ – ”וְהִנֵּה הַ שֵ ם נִצָּב עָלָיו“ following verse 4 When we desire to sanctify ourselves, Hashem will guard us with a protection beyond nature.3F The Ladder Within Ya’acov’s ladder teaches us about how our relationship with Hashem in truth is a relationship with our own inner core. -

Full Details of the Hamakom Jewish Mindfulness Meditation Retreat

Full Details of the HaMakom Jewish Mindfulness Meditation Retreat Friday 27 – Monday 30 May, 2016 INTRODUCTION A unique weekend dedicated to the practice of Jewish Mindfulness Meditation and the deepening of our wellbeing and spiritual lives with Rabbi Dr James Jacobson Maisels, one of the world’s leading Jewish Mindfulness Meditation Teachers. Together we will explore how the practice of meditation helps us to understand better the nature of our minds and to cultivate the qualities of wellbeing, contentment, gratitude, forgiveness, compassion and wisdom. Daily instruction in meditation will help guide both beginning and advanced practitioners into the sacred space of the retreat process. There will also be times for questions and answers, as well as small group and private interviews with the instructors. The week will include a deep celebration of Shabbat, followed by a chance to hear of each other’s experience as the retreat comes to a close. The retreat also includes daily periods of prayer, chant and Qi Gong. The form of prayer consists of chanting excerpts from the liturgy interspersed with silence. Those who follow traditional rules for davvening will be able to pray separately to fulfil their obligations. All activities are optional. We welcome people of all ages and of all faiths and none. Suitable for beginners and experienced practitioners. COSTS, ACCOMODATION & FOOD HaMakom endeavours to keep costs as low as possible and aims to be accessible to everyone, regardless of financial circumstances. The price of our retreats is set to reflect just the basic costs of arranging the retreat and includes kosher vegetarian meals and basic, shared accommodation in dormitories at Skeet House Jewish Retreat Centre. -

ANGER in JUDAISM by Rabbi Dr

ANGER IN JUDAISM by Rabbi Dr. Nachum Amsel July 23, 2018 This essay is reprinted from the book, “The Encyclopedia of Jewish Values” published by Urim, or the upcoming books, “The Encyclopedia of Jewish Values: Man to Man” or “The Encyclopedia of Jewish Values: Man to G-d” to be published in the future. This essay is not intended as a source of practical halachic (legal) rulings. For matters of halachah, please consult a qualified posek (rabbi). Although anger is a universal human emotion, it is nevertheless a very unusual sensation and reaction to something that upsets us. There are many variables involved when people get angry, including how angry they get or how long they stay angry after experiencing a threatening, hurtful, or unexpected situation.The definition of anger is “a strong feeling of displeasure and belligerence aroused by a wrong.” It is an emotion related to one's psychological interpretation of having been offended, wronged or denied something that was expected, and it is characterized by a tendency to react through retaliation. Anger as a normal emotion involves a strong uncomfortable and emotional response to a perceived provocation. The external expression of anger can be found in facial expressions, body language, physiological responses, and at times in acts of aggression. Anger is unusual in that some people can control it while others cannot, and everyone expresses his or her anger differently. Sometimes it seems that anger only makes things worse. So why do people get angry? How much control over this emotion do we really have? Why do reactions vary so widely between people or even day to day within the same person? What are the benefits and drawbacks of expressing ourselves and being or getting angry? We will attempt to address some of these questions as we discover the Jewish attitude towards anger through the traditional sources, since the Torah and rabbis have much to say about anger. -

124900176.Pdf

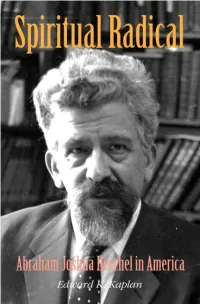

Spiritual Radical EDWARD K. KAPLAN Yale University Press / New Haven & London [To view this image, refer to the print version of this title.] Spiritual Radical Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 Published with assistance from the Mary Cady Tew Memorial Fund. Copyright © 2007 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Bodoni type by Binghamton Valley Composition. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Kaplan, Edward K., 1942– Spiritual radical : Abraham Joshua Heschel in America, 1940–1972 / Edward K. Kaplan.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-11540-6 (alk. paper) 1. Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 1907–1972. 2. Rabbis—United States—Biography. 3. Jewish scholars—United States—Biography. I. Title. BM755.H34K375 2007 296.3'092—dc22 [B] 2007002775 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Committee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10987654321 To my wife, Janna Contents Introduction ix Part One • Cincinnati: The War Years 1 1 First Year in America (1940–1941) 4 2 Hebrew Union College -

Bronstein: Kaballah and Art

Studies in Visual Communication Volume 7 Issue 2 Spring 1981 Article 8 1981 Bronstein: Kaballah and Art Laurin Raiken New York University School of the Arts and the Gallatin Division Recommended Citation Raiken, L. (1981). Bronstein: Kaballah and Art. 7 (2), 89-93. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/ svc/vol7/iss2/8 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol7/iss2/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bronstein: Kaballah and Art This reviews and discussion is available in Studies in Visual Communication: https://repository.upenn.edu/svc/vol7/ iss2/8 Reviews and Discussion 89 to history; his writing, a pathway to a new set of doors into a living , visual history of ideas. Leo Bronstein. Kaballah and Art. Kabbalah and Art is an achievement of Leo Bron Distributed for Brandeis University Press by the stein's maturity. Earlier he had written: University Press of New England, Box 979, Hanover, Maturity is the discovery of childhood 's prophecy. History is N.H. 03755, 1980. 144 pp. , 49 illustrations (one in the discovery of prehistory's prophecy. Freedom or integrity color). $20.00 (cloth). of expression in maturity depends upon the degree of loyalty to this prophecy. [ibid .:ix] Reviewed by Laurin Raiken Kabbalah and Art begins with Leo Bronstein's invit New York University School of the Arts and the Gallatin ing the reader to recognize that our rare meetings with Division "an object of life and creation" are our meeting with friendship. Such an encounter is "the meeting with ...as ibn Latif, the Spanish poet-Kabbalist of the early your spirituality" (p. -

1 I Have Been Reading Several Most Interesting Chapters on the Thinking of Roberto Assagioli, the Father of Transpersonal Psycho

I have been reading several most interesting chapters on the thinking of Roberto Assagioli, the father of Transpersonal Psychology, as related to Kabbalah. These appear in "Opening the Inner Gates: New Paths in Kabbalah and Psychology" edited by Edward Hoffman. One chapter entitled "Psychosynthesis and Kabbalah" is a comparative study between Assagioli's "Egg diagram" and the Kabbalistic Tree of Life. It is certainly most interesting with lots of practical information, but it is in another chapter entitled "Jewish Meditation: Healing Ourselves and Our Relationship" that one realizes the influence of Kabbalistic thinking had on Assagioli. Here is a quote for your interest and perusal from that very exciting chapter written by Sheldon Z. Kramer. "The Zohar, a major Kabbalistic text, states that the soul has three strands. These three strands are compared to a candle flame. The first part of the candle flame is located near the wick and reflects a black and blue light that is always changing. This lower light is considered the nefesh, or animal soul. The nefesh may be likened to Sigmund Freud's idea of the id, ego, and superego: it is those parts of the personality that are always in flux, owing to inner or outer reactivity based on internal and external desires. Contained within the animal soul is also a variety of different ego identifications based on early childhood experiences that forms one's personality, such as 'the ambitious one,' 'the procrastinator,' or 'the frightened child.' Located directly above the black and blue light is a steady yellow glow in the center of the flame; this section is called the ruach, the divine wind, breath, or spirit. -

L:Ir9111, NORTH AMERICA: 866·550·4EYE, GREAT BRITAIN: 0800 1700 EYE [email protected]

WITHIN ISRAEL:ir9111, NORTH AMERICA: 866·550·4EYE, GREAT BRITAIN: 0800 1700 EYE WWW.EYESQUAD.ORG; [email protected] I . -------- ·-·- ---------------- ~ -------- ------------------- -------- --- ---------- ------- --·-=l ··· . h IN THIS ISSUE ewts•. LETTER FROM JERUSALEM 6 UNiTY Is Nor ON THE HoR1zoN, /BSEl{VER Yonoson Rosenb!urn THE JEWISH OBSERVER (ISSN) 0021-6615 IS PllBl.lSHED 10 NE!THER HEKHSHE.R, NOR TZEDEK, _\IO"ITHLY, EXCEPT JU!.Y & Al!GL'Sl Rabbi Avi Shafran Ai'iD A COMIHNl':fl !SSliE FOi~ J..\"IU.\JniFEllRUi\RY. BY THE AGPOATH ISRAf;L OF .l\MERIC..\. 42 BHO ..\!lWAY. :'JEW YonK. NY iooo4. ELUL: PREPARING FOR A NEW START PERIOOlCAl.S POSTAGE PAID IN Nt\V YORK, NY. SliBSCRll'TJON S25.00/Y~.All; 14 STAYING ON TRACK IN TURBULENT TtMES, 2 YL\RS. 548.oo::; YEARS, $69.00. 0l 1TS1DE OF THE UNITED STATES (L'S Rabbi Aaron Brafrnan fll"IOS DRA\VN ON ."i US B."-NK ON!.Y) S!$.OO ~URCllARGE Pl'll Yb\R. SINGl.r NEVER AGAIN AGAll'l, COPY S:;.so: Otr!SJOf: NY •\llEA $3,95; 18 FOllHG:-1 54.50. 1Vafta!i Versch/eisser POSTMASTER: SF"'D ADDRESS CHANGES TO! 21 FROM BE.4R STEARNS TO BAVA METZ/A, TEL 212-797-9000, FAX 646-254-1600 PRlNTt·:o JN THE USA f.!..ndrevv .f\Jeff RABBI NlSSON Wotrri'i. Editor 26 FROM KoLLEL ro THE WoRKPLt,cE, f-.'ditoria/ floord Yos1 l~eber RAUB! JOSEPH f:1.1As, Omirmrm RABI\! ABBA BHliDN) Jos1·:PH Fn1t·:DENSON 29 SHOFAROS: ARE THEY ALL THE Sr\ME? RABBI YISl~Ol-:l. M1,:l11 i<IRZNER 1 R.•\lllH NOSSON Sct!UtMA"i Rabhi Ari Z. -

Communal (1970)

Communal Jewish Communal Services: Programs and Finances M.AN, Y TYPES of Jewish communal services are provided under organized Jewish sponsorship, although some needs of Jews (and of non- Jews) are exclusively individual or governmental responsibilities. While the aim is to serve Jewish community needs, some services may be made avail- able also to the general community. Most services are provided at the geographic point of need, but their financing may be secured from a wider area: nationally or internationally. This report deals with the financial contribution of American Jewry to domestic and global services and, to a limited extent, with aid by Jews in other parts of the free world. Geographic classification of services, i.e. local, national, overseas, is based on physical location of areas of program operation. A more fundamental classification would be in terms of type of services provided or needs met, regardless of geography. On this basis, Jewish com- munal services would encompass: • Economic aid, mainly overseas: largely a function of government in the United States. • Migration aid: a global function involving movement between countries, mainly to Israel, but also to the United States and other areas in substantial numbers at particular periods. • Absorption and resettlement of migrants: also a global function in- volving economic aid, housing, job placement or retraining, and social adjust- ment. The complexity of the task is related to the size of movement, the background of migrants, the economic and social viability or absorptive potential of the communities in which resettlement takes place, and the availability of resources and structures for absorption in the host communities.