Beyond Anthropomorphism (Sue Savage

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Gorilla Beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26

Gorilla beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia ChordataMammaliaPrimatesHominidae Scientific Gorilla beringei Name: Species Matschie, 1903 Authority: Infra- specific See Gorilla beringei ssp. beringei Taxa See Gorilla beringei ssp. graueri Assessed: Common Name(s): English –Eastern Gorilla French –Gorille de l'Est Spanish–Gorilla Oriental TaxonomicMittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B. and Wilson D.E. 2013. Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume Source(s): 3 Primates. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. This species appeared in the 1996 Red List as a subspecies of Gorilla gorilla. Since 2001, the Eastern Taxonomic Gorilla has been considered a separate species (Gorilla beringei) with two subspecies: Grauer’s Gorilla Notes: (Gorilla beringei graueri) and the Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) following Groves (2001). Assessment Information [top] Red List Category & Criteria: Critically Endangered A4bcd ver 3.1 Year Published: 2016 Date Assessed: 2016-04-01 Assessor(s): Plumptre, A., Robbins, M. & Williamson, E.A. Reviewer(s): Mittermeier, R.A. & Rylands, A.B. Contributor(s): Butynski, T.M. & Gray, M. Justification: Eastern Gorillas (Gorilla beringei) live in the mountainous forests of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, northwest Rwanda and southwest Uganda. This region was the epicentre of Africa's "world war", to which Gorillas have also fallen victim. The Mountain Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei beringei), has been listed as Critically Endangered since 1996. Although a drastic reduction of the Grauer’s Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei graueri), has long been suspected, quantitative evidence of the decline has been lacking (Robbins and Williamson 2008). During the past 20 years, Grauer’s Gorillas have been severely affected by human activities, most notably poaching for bushmeat associated with artisanal mining camps and for commercial trade (Plumptre et al. -

Surrogate Motherhood

Surrogate Motherhood Page ii MEDICAL ETHICS SERIES David H. Smith and Robert M. Veatch, Editors Page iii Surrogate Motherhood Politics and Privacy Edited by Larry Gostin Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis Page iv This book is based on a special issue of Law, Medicine & Health Care (16:1–2, spring/summer, 1988), a journal of the American Society of Law & Medicine. Many of the essays have been revised, updated, or corrected, and five appendices have been added. ASLM coordinator of book production was Merrill Kaitz. © 1988, 1990 American Society of Law & Medicine All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permission constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1984. Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Surrogate motherhood : politics and privacy / edited by Larry Gostin. p. cm. — (Medical ethics series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0253326044 (alk. paper) 1. Surrogate mothers—Legal status, laws, etc.—United States. 2. Surrogate mothers—Civil rights—United States. 3. Surrogate mothers—United States. I. Gostin, Larry O. (Larry Ogalthorpe) II. Series. KF540.A75S87 1990 346.7301'7—dc20 [347.30617] 8945474 CIP 1 2 3 4 5 94 93 92 91 90 Page v Contents Introduction ix Larry Gostin CIVIL LIBERTIES A Civil Liberties Analysis of Surrogacy Arrangements 3 Larry Gostin Procreative Liberty and the State's Burden of Proof in Regulating Noncoital 24 Reproduction John A. -

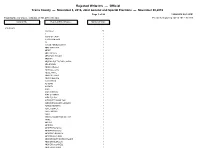

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

Himpanzee C Chronicle

An Exclusive Publication Produced By Chimp Haven, Inc. VOLUME IX ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2009 HIMPANZEE www.chimphaven.org C CHRONICLE INSIDE THIS ISSUE: PET CHIMPANZEES HAVE BEEN IN THE NEWS THIS YEAR. Travis, who attacked a woman in Connecticut, was shot to death. Timmie was shot in Missouri when he escaped and attacked a deputy. There are countless more pet chimpanzees living in private homes throughout the United States. This edition of the Chimpanzee Chronicle discusses this serious issue. Please share it with others. WHY CHIMPANZEES DON’T MAKE GOOD PETS By Linda Brent, PhD, President and Director When chimpanzees become pets, the outcome for them or their human “family” is rarely a good one. Chimpanzees are large, wild animals who are highly intelligent and require a great deal of socialization with their mother and other chimpanzees. Sanctuaries most often hear about pet chimpanzees when they reach adolescence and are too difficult to manage any longer. Often, they bite someone or break household items. Sometimes they get loose or seriously attack a person. Generally speaking, these actions are part of normal chimpanzee behavior. An adolescent male chimpanzee begins to try to dominate others as he works his way up the dominance hierarchy or social ladder. He does this by BOARD OF displaying, hitting and throwing objects, and sometimes attacking others. Pet chimpanzees do not have the benefit of a normal social group as an outlet for their behavior, and often these DIRECTORS behaviors are directed at human caregivers or strangers. Since chimpanzees can easily weigh as much as a person—but are far stronger—they are obviously dangerous animals to have in the Thomas Butler, D.V.M., M.S. -

Supreme Court of the State of New York County of New York ______

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK __________________________________________________ In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, MEMORANDUM OF Petitioner, LAW IN SUPPORT OF -against- PETITION FOR HABEAS CORPUS CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. Index No. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents. __________________________________________________ Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5 Dunhill Road New Hyde Park, NY 11040 Phone (516) 747-4726 Steven M. Wise, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5195 NW 112th Terrace Coral Springs, FL 33076 Phone (954) 648-9864 Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. Subject to pro hac vice admission January_____, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................................ v I. SUMMARY OF NEW GROUNDS AND FACTS NEITHER PRESENTED NOR DETERMINED IN NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., EX REL. KIKO v. PRESTI OR NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC. ON BEHALF OF TOMMY v. LAVERY. ............................................................................................................. 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................... 6 III. STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................... -

Human Uniqueness in the Age of Ape Language Research1

Society and Animals 18 (2010) 397-412 brill.nl/soan Human Uniqueness in the Age of Ape Language Research1 Mary Trachsel University of Iowa [email protected] Abstract This paper summarizes the debate on human uniqueness launched by Charles Darwin’s publi- cation of The Origin of Species in 1859. In the progress of this debate, Noam Chomsky’s intro- duction of the Language-Acquisition Device (LAD) in the mid-1960s marked a turn to the machine model of mind that seeks human uniqueness in uniquely human components of neu- ral circuitry. A subsequent divergence from the machine model can be traced in the short his- tory of ape language research (ALR). In the past fifty years, the focus of ALR has shifted from the search for behavioral evidence of syntax in the minds of individual apes to participant- observation of coregulated interactions between humans and nonhuman apes. Rejecting the computational machine model of mind, the laboratory methodologies of ALR scientists Tetsuro Matsuzawa and Sue Savage-Rumbaugh represent a worldview coherent with Darwin’s continu- ity hypothesis. Keywords ape language research, artificial intelligence, Chomsky, comparative psychology, Darwin, human uniqueness, social cognition Introduction Nothing at first can appear more difficult to believe than that the more complex organs and instincts should have been perfected, not by means superior to, though analogous with, human reason, but by the accumulation of innumerable slight variations, each good for the individual possessor. (Darwin, 1989b, p. 421) With the publication of The Origin of Species (1859/1989a), Charles Darwin steered science directly into a conversation about human uniqueness previ- ously dominated by religion and philosophy. -

The Humanities and Posthumanism

english edition 1 2015 The Humanities and Posthumanism issue editor GRZEGORZ GROCHOWSKI MICHAł PAWEł MARKOWSKI Humanities: an Unfinished Project E WA DOMAńSKA Ecological Humanities R YSZARD NYCZ Towards Innovative Humanities: The Text as a Laboratory. Traditions, Hypotheses, Ideas O LGA CIELEMęCKA Angelus Novus Looks to the Future. On the Anti-Humanism Which Overcomes Nothingness SYZ MON WRÓBEL Domesticating Animals: A Description of a Certain Disturbance teksty drugie · Institute of Literary Research Polish Academy of Science index 337412 · pl issn 0867-0633 EDITORIAL BOARD Agata Bielik-Robson (uk), Włodzimierz Bolecki, Maria Delaperrière (France), Ewa Domańska, Grzegorz Grochowski, Zdzisław Łapiński, Michał Paweł Markowski (usa), Maciej Maryl, Jakub Momro, Anna Nasiłowska (Deputy Editor-in-Chief), Leonard Neuger (Sweden), Ryszard Nycz (Editor-in-Chief), Bożena Shallcross (usa), Marta Zielińska, Tul’si Bhambry (English Translator and Language Consultant), Justyna Tabaszewska, Marta Bukowiecka (Managing Editor) ADVISORY BOARD Edward Balcerzan, Stanisław Barańczak (usa) , Małgorzata Czermińska, Paweł Dybel, Knut Andreas Grimstad (Norway), Jerzy Jarzębski, Bożena Karwowska (Canada), Krzysztof Kłosiński, Dorota Krawczyńska, Vladimir Krysinski (Canada), Luigi Marinelli (Italy ), Arent van Nieukerken (Holland), Ewa Rewers, German Ritz (Switzerland), Henryk Siewierski (Brasil), Janusz Sławiński , Ewa Thompson (usa), Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, Tamara Trojanowska (Canada), Alois Woldan (Austria), Anna Zeidler-Janiszewska ADDRESS Nowy Świat 72, room. -

Epidemiology and Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium Spp. in Humans, Wild Primates, and Domesticated Animals in the Greater Gombe Ecosystem, Tanzania

RESEARCH ARTICLE Epidemiology and Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in Humans, Wild Primates, and Domesticated Animals in the Greater Gombe Ecosystem, Tanzania Michele B. Parsons1,2, Dominic Travis3, Elizabeth V. Lonsdorf4, Iddi Lipende5 Dawn M. Anthony Roellig2,5, Shadrack Kamenya5, Hongwei Zhang6, Lihua Xiao2 Thomas R. Gillespie1* 1 Program in Population Biology, Ecology, and Evolution and Departments of Environmental Sciences and Environmental Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, 2 Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, 3 College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America, 4 Department of Psychology, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, United States of America, 5 The Jane Goodall Institute, Kigoma, Tanzania, OPEN ACCESS 6 Institute of Parasite Disease Prevention and Control, Henan Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Zhengzhou, China Citation: Parsons MB, Travis D, Lonsdorf EV, Lipende I, Roellig DMA, Kamenya S, et al. (2015) * [email protected] Epidemiology and Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in Humans, Wild Primates, and Domesticated Animals in the Greater Gombe Ecosystem, Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10(2): Abstract e0003529. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003529 Cryptosporidium is an important zoonotic parasite globally. Few studies have examined the Editor: Stephen Baker, Oxford University Clinical ecology and epidemiology of this pathogen in rural tropical systems characterized by high Research Unit, VIETNAM rates of overlap among humans, domesticated animals, and wildlife. We investigated risk Received: October 31, 2014 factors for Cryptosporidium infection and assessed cross-species transmission potential Accepted: January 9, 2015 among people, non-human primates, and domestic animals in the Gombe Ecosystem, Published: February 20, 2015 Kigoma District, Tanzania. -

Kiswahili for Foreigners ( Pdfdrive.Com ) (1).Pdf

KISWAHILI FOR FOREIGNERS By AMIR. A. MOHAMED FIRST EDITION 1993 SECOND EDITION 2000 THIRD EDITION 2009 © Create Space 0f Amazon.com CONTENTS – YALIYOMO Page FOREWORD Ukurasa I INTRODUCTION – 1 KITANGULIZI II THE SOUND 2 SYSTEM III ROOTS, STEMS, 3 AFFIXES IV NOUNS AND 4 CLASSIFICATION V VERB AND THEIR 11 TENSES VI COMPOUND 16 TENSES VII PRONOUNS 17 VIII ADJECTIVES 22 X ADVERBS 25 XI PREPOSITONS 29 AND CONJUCTIONS XII VOBABULARY – 33 MSAMIATI XIII KISWAHILI 46 SAYING – MISEMO YA KISWAHILI XIV EXERCISE – 52 MZOESI XV KISWAHILI WORD 65 – 124 POWER IX KISWAHILI SLANGS & BOMBASTCS – SIMO ZA KISWAHILI 125-174 IIX BIBLIOGRAPHY FOREWORD Kiswahili*is a growing language in Africa and the world as a whole. There are historians who believe that Kiswahili is probably nine hundred years old and like other languages, its significance can be proved by the growing demand of its usage and the constant increase in the world of the need to learn and to speak Kiswahili. The world is entering into the new millennium and we are all striving to have a better life and a peaceful world. Therefore, it has now become increasingly necessary for foreigners to learn Kiswahili no matter what they do and no matter where they are. Besides the social and economic dimensions of the language abroad like working in East Africa or just on holidays, learning the language may help to improve the race relations between Africans and foreigners. It’s time to learn to understand each other and to know how to make perfect moves in our lives. History of the language reveals that Kiswahili is of Bantu origin but heavily loaded with Arabic, English, Indian and other oriental words. -

Andrews Tove.Pdf (1.498Mb)

MASTEROPPGAVE Project Sci-fi: I n v i t i n g a l i e n s a n d r o b o t s i n t o t h e E n g l i s h c l a s s r o o m , h o w f i c t i o n a l c u l t u r e s c a n p r o m o t e d e v e l o p m e n t o f i n t e r c u l t u r a l c o m p e t e n c e Tove Lora Andrews 06.11.2019 Master Fremmedspråk i skolen Avdeling for økonomi, språk og samfunsdag Abstract Little focus has been placed on why English teachers in Norway should favour intercultural competence over cultural facts. Yet knowing cultural facts do not make pupils effective communicators, which is the purpose for language learning. Intercultural competence prepares pupils for intercultural encounters, through a conglomeration of open attitudes, accurate knowledge, insightful understanding, appropriate skills, and practical application. Literature is a common and efficient means of exploring culture and intercultural encounters within a classroom setting. Both multicultural literature and science fiction explore cultural themes and identity, but the latter explores a broader range of contemporary topics. Therefore, this thesis sought to explore to what extent science fiction could be used to promote intercultural competence in the English classroom. Analysing fiction and imaginary cultures circumvented pitfalls common to multicultural literature. -

In Chimpanzees (Pan Troglodytes)

2018, 31 David Washburn Special Issue Editor Peer-reviewed Assessing Distinctiveness Effects and “False Memories” in Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Bonnie M. Perdue1, Andrew J. Kelly2, and Michael J. Beran3 1 Agnes Scott College 2 Georgia Gwinnett College 3 Georgia State University There are many parallels between human and nonhuman animal cognitive abilities, suggesting an evolutionary basis for many forms of cognition, including memory. For instance, past research has found that 2 chimpanzees exhibited an isolation effect, or improved memory for semantically distinctive items on a list (Beran, 2011). These results support the notion that chimpanzees are capable of semantic, relational processing in memory and introduce the possibility that other effects observed in humans, such as distinctiveness effects or false memories, may be present in nonhuman species. The Deese-Roediger-McDermott (DRM) paradigm is a commonly- used task to explore these phenomena, and it was adapted for use with chimpanzees. We tested 4 chimpanzees for isolation effects during encoding, distinctiveness effects during recognition, and potential “false memories” generated by the DRM paradigm by presenting a serial recognition memory task. The isolation effect previously reported (Beran, 2011) was not replicated in this experiment. Two of four chimpanzees showed improved recognition performance when information about distinctiveness could be used to exclude incorrect responses. None of the chimpanzees were significantly impaired in the “false memory” condition. However, limitations to this approach are discussed that require caution about assuming identical memory processes in these chimpanzees and in humans. Keywords: chimpanzees, memory, DRM illusion, isolation effect, false memory, distinctiveness, relational processing Research in the 20th century redefined our understanding of ape minds, especially the pioneering work of Dr.