The Humanities and Posthumanism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Complete Stories by Franz Kafka

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka Back Cover: "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. The foreword by John Updike was originally published in The New Yorker. -

Current, August 22, 2005

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Current (2000s) Student Newspapers 8-22-2005 Current, August 22, 2005 University of Missouri-St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/current2000s Recommended Citation University of Missouri-St. Louis, "Current, August 22, 2005" (2005). Current (2000s). 261. https://irl.umsl.edu/current2000s/261 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Current (2000s) by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. VOLUME 38 Aug. 22, 2005 ISSUE 1156 Your source for campus news and information See page 7 Greeks get ready for rush THECURRENTONUNLCOM -------------____________________________________ UNIVIRSITY OF MISSOURI - ST. lOUIS Floyd hits the road with fixed tuition proposal UM President receives positive but skeptical response BY PAUL HACKBARTH UM tuition increases 2001-2006 News Editor 19.8% MARCELINE, Mo. - In Walt 20 Disney's hometown, Anne Cordray, a single parent of two, is worried about 14.8% the costs of sending her oldest daugh ter to college. Tuesday night, she came to hear UM President Elson Floyd discuss his proposal to guaran tee a fixed tuition rate for two to five years for new students. Cordray's daughter, Whitney, is a senior in high school and hopes to attend college in Missouri this time next year. Cordray and her daughter are looking at different schools, decid ing on which one is best for them, both academically and financially. Floyd has been traveling across the Source: Memo from President Floyd to Board of Curators, June 15, 2005 state in an effort to hear Missourians' views on the tuition freeze. -

Supreme Court of the State of New York County of New York ______

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK __________________________________________________ In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, MEMORANDUM OF Petitioner, LAW IN SUPPORT OF -against- PETITION FOR HABEAS CORPUS CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. Index No. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents. __________________________________________________ Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5 Dunhill Road New Hyde Park, NY 11040 Phone (516) 747-4726 Steven M. Wise, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5195 NW 112th Terrace Coral Springs, FL 33076 Phone (954) 648-9864 Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. Subject to pro hac vice admission January_____, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................................ v I. SUMMARY OF NEW GROUNDS AND FACTS NEITHER PRESENTED NOR DETERMINED IN NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., EX REL. KIKO v. PRESTI OR NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC. ON BEHALF OF TOMMY v. LAVERY. ............................................................................................................. 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................... 6 III. STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................... -

Human Uniqueness in the Age of Ape Language Research1

Society and Animals 18 (2010) 397-412 brill.nl/soan Human Uniqueness in the Age of Ape Language Research1 Mary Trachsel University of Iowa [email protected] Abstract This paper summarizes the debate on human uniqueness launched by Charles Darwin’s publi- cation of The Origin of Species in 1859. In the progress of this debate, Noam Chomsky’s intro- duction of the Language-Acquisition Device (LAD) in the mid-1960s marked a turn to the machine model of mind that seeks human uniqueness in uniquely human components of neu- ral circuitry. A subsequent divergence from the machine model can be traced in the short his- tory of ape language research (ALR). In the past fifty years, the focus of ALR has shifted from the search for behavioral evidence of syntax in the minds of individual apes to participant- observation of coregulated interactions between humans and nonhuman apes. Rejecting the computational machine model of mind, the laboratory methodologies of ALR scientists Tetsuro Matsuzawa and Sue Savage-Rumbaugh represent a worldview coherent with Darwin’s continu- ity hypothesis. Keywords ape language research, artificial intelligence, Chomsky, comparative psychology, Darwin, human uniqueness, social cognition Introduction Nothing at first can appear more difficult to believe than that the more complex organs and instincts should have been perfected, not by means superior to, though analogous with, human reason, but by the accumulation of innumerable slight variations, each good for the individual possessor. (Darwin, 1989b, p. 421) With the publication of The Origin of Species (1859/1989a), Charles Darwin steered science directly into a conversation about human uniqueness previ- ously dominated by religion and philosophy. -

The Complete Stories

The Complete Stories by Franz Kafka a.b.e-book v3.0 / Notes at the end Back Cover : "An important book, valuable in itself and absolutely fascinating. The stories are dreamlike, allegorical, symbolic, parabolic, grotesque, ritualistic, nasty, lucent, extremely personal, ghoulishly detached, exquisitely comic. numinous and prophetic." -- New York Times "The Complete Stories is an encyclopedia of our insecurities and our brave attempts to oppose them." -- Anatole Broyard Franz Kafka wrote continuously and furiously throughout his short and intensely lived life, but only allowed a fraction of his work to be published during his lifetime. Shortly before his death at the age of forty, he instructed Max Brod, his friend and literary executor, to burn all his remaining works of fiction. Fortunately, Brod disobeyed. Page 1 The Complete Stories brings together all of Kafka's stories, from the classic tales such as "The Metamorphosis," "In the Penal Colony" and "The Hunger Artist" to less-known, shorter pieces and fragments Brod released after Kafka's death; with the exception of his three novels, the whole of Kafka's narrative work is included in this volume. The remarkable depth and breadth of his brilliant and probing imagination become even more evident when these stories are seen as a whole. This edition also features a fascinating introduction by John Updike, a chronology of Kafka's life, and a selected bibliography of critical writings about Kafka. Copyright © 1971 by Schocken Books Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Schocken Books Inc., New York. Distributed by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York. -

Animal Studies Ecocriticism and Kafkas Animal Stories 4

Citation for published version: Goodbody, A 2016, Animal Studies: Kafka's Animal Stories. in Handbook of Ecocriticism and Cultural Ecology. Handbook of English and American Studies, vol. 2, De Gruyter, Berlin, pp. 249-272. Publication date: 2016 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication University of Bath Alternative formats If you require this document in an alternative format, please contact: [email protected] General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 26. Sep. 2021 Animal Studies: Kafka’s Animal Stories Axel Goodbody Franz Kafka, who lived in the city of Prague as a member of the German-speaking Jewish minority, is usually thought of as a quintessentially urban author. The role played by nature and the countryside in his work is insignificant. He was also no descriptive realist: his domain is commonly referred to as the ‘inner life’, and he is chiefly remembered for his depiction of outsider situations accompanied by feelings of inadequacy and guilt, in nightmarish scenarios reflecting the alienation of the modern subject. Kafka was only known to a small circle of when he died of tuberculosis, aged 40, in 1924. However, his enigmatic tales, bafflingly grotesque but memorably disturbing because they resonate with readers’ own experiences, anxieties and dreams, their sense of marginality in family and society, and their yearning for self-identity, rapidly acquired the status of world literature after the Holocaust and the Second World War. -

Kiswahili for Foreigners ( Pdfdrive.Com ) (1).Pdf

KISWAHILI FOR FOREIGNERS By AMIR. A. MOHAMED FIRST EDITION 1993 SECOND EDITION 2000 THIRD EDITION 2009 © Create Space 0f Amazon.com CONTENTS – YALIYOMO Page FOREWORD Ukurasa I INTRODUCTION – 1 KITANGULIZI II THE SOUND 2 SYSTEM III ROOTS, STEMS, 3 AFFIXES IV NOUNS AND 4 CLASSIFICATION V VERB AND THEIR 11 TENSES VI COMPOUND 16 TENSES VII PRONOUNS 17 VIII ADJECTIVES 22 X ADVERBS 25 XI PREPOSITONS 29 AND CONJUCTIONS XII VOBABULARY – 33 MSAMIATI XIII KISWAHILI 46 SAYING – MISEMO YA KISWAHILI XIV EXERCISE – 52 MZOESI XV KISWAHILI WORD 65 – 124 POWER IX KISWAHILI SLANGS & BOMBASTCS – SIMO ZA KISWAHILI 125-174 IIX BIBLIOGRAPHY FOREWORD Kiswahili*is a growing language in Africa and the world as a whole. There are historians who believe that Kiswahili is probably nine hundred years old and like other languages, its significance can be proved by the growing demand of its usage and the constant increase in the world of the need to learn and to speak Kiswahili. The world is entering into the new millennium and we are all striving to have a better life and a peaceful world. Therefore, it has now become increasingly necessary for foreigners to learn Kiswahili no matter what they do and no matter where they are. Besides the social and economic dimensions of the language abroad like working in East Africa or just on holidays, learning the language may help to improve the race relations between Africans and foreigners. It’s time to learn to understand each other and to know how to make perfect moves in our lives. History of the language reveals that Kiswahili is of Bantu origin but heavily loaded with Arabic, English, Indian and other oriental words. -

Franz Kafka - Quotes

Franz Kafka - Quotes It is the thousandth forgetting of a dream dreamt a thousand times and forgotten a thousand times, and who can damn us merely for forgetting for the thousandth time? - Investigations Of A Dog Ours is a lost generation, it may be, but it is more blameless than those earlier generations. - Investigations Of A Dog So long as you have food in your mouth, you have solved all questions for the time being. - Investigations Of A Dog You need not leave your room. Remain sitting at your table and listen. You need not even listen, simply wait, just learn to become quiet, and still, and solitary. The world will freely offer itself to you to be unmasked. It has no choice; it will roll in ecstasy at your feet. - Journals My peers, lately, have found companionship through means of intoxication--it makes them sociable. I, however, cannot force myself to use drugs to cheat on my loneliness--it is all that i have--and when the drugs and alcohol dissipate, will be all that my peers have as well. - Journals A book should serve as the ax for the frozen sea within us. - Journals A man of action forced into a state of thought is unhappy until he can get out of it. - Journals Anyone who keeps the ability to see beauty never grows old. - Journals By believing passionately in something that still does not exist, we create it. The nonexistent is whatever we have not sufficiently desired. - Journals In me, by myself, without human relationship, there are no visible lies. -

Andrews Tove.Pdf (1.498Mb)

MASTEROPPGAVE Project Sci-fi: I n v i t i n g a l i e n s a n d r o b o t s i n t o t h e E n g l i s h c l a s s r o o m , h o w f i c t i o n a l c u l t u r e s c a n p r o m o t e d e v e l o p m e n t o f i n t e r c u l t u r a l c o m p e t e n c e Tove Lora Andrews 06.11.2019 Master Fremmedspråk i skolen Avdeling for økonomi, språk og samfunsdag Abstract Little focus has been placed on why English teachers in Norway should favour intercultural competence over cultural facts. Yet knowing cultural facts do not make pupils effective communicators, which is the purpose for language learning. Intercultural competence prepares pupils for intercultural encounters, through a conglomeration of open attitudes, accurate knowledge, insightful understanding, appropriate skills, and practical application. Literature is a common and efficient means of exploring culture and intercultural encounters within a classroom setting. Both multicultural literature and science fiction explore cultural themes and identity, but the latter explores a broader range of contemporary topics. Therefore, this thesis sought to explore to what extent science fiction could be used to promote intercultural competence in the English classroom. Analysing fiction and imaginary cultures circumvented pitfalls common to multicultural literature. -

The Fragments Around Franz Kafka's “A Report to an Academy”

humanities Article Narrative Transformed: The Fragments around Franz Kafka’s “A Report to an Academy” Doreen Densky Department of German, New York University, 19 University Place, 3rd Floor, New York, NY 10003, USA; [email protected] Academic Editor: Joela Jacobs Received: 7 February 2017; Accepted: 6 April 2017; Published: 10 April 2017 Abstract: Franz Kafka’s “A Report to an Academy”, in which the ape-turned-human Rotpeter provides a narrative account of his life, has been scrutinized with regard to its allegorical, scientific, and historical implications. This article shifts the focus toward the narrative set-up by closely reading the transformation that can be traced in the sequence of several narrative attempts found in Kafka’s manuscripts. Analyzing the fragments around this topic, I show how Kafka probes different angles—from a meeting between a first-person narrator and Rotpeter’s impresario and a dialogue between the narrator and Rotpeter, via the well-known “Report” itself, on to a letter by one of Rotpeter’s former teachers—that reveal a narrative transformation equally important as the metamorphosis from animal to human. The focus on the narrative constellations and on the lesser-known constitutive margins of the “Report” help to better understand, moreover, the complex relationship between immediacy and mediation, the ethnological concern of speech for the self and the unknown animal other, and poetological questions of production, representation, and reception. Keywords: animal narrators; human-animal studies; Franz Kafka; manuscripts; speaking-for; narrative representation; literary representation 1. Introduction Franz Kafka’s famous text narrated by an ape who has become human, “A Report to an Academy” (“Ein Bericht für eine Akademie”), was penned one hundred years ago, in 1917 [1–5]. -

In Chimpanzees (Pan Troglodytes)

2018, 31 David Washburn Special Issue Editor Peer-reviewed Assessing Distinctiveness Effects and “False Memories” in Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Bonnie M. Perdue1, Andrew J. Kelly2, and Michael J. Beran3 1 Agnes Scott College 2 Georgia Gwinnett College 3 Georgia State University There are many parallels between human and nonhuman animal cognitive abilities, suggesting an evolutionary basis for many forms of cognition, including memory. For instance, past research has found that 2 chimpanzees exhibited an isolation effect, or improved memory for semantically distinctive items on a list (Beran, 2011). These results support the notion that chimpanzees are capable of semantic, relational processing in memory and introduce the possibility that other effects observed in humans, such as distinctiveness effects or false memories, may be present in nonhuman species. The Deese-Roediger-McDermott (DRM) paradigm is a commonly- used task to explore these phenomena, and it was adapted for use with chimpanzees. We tested 4 chimpanzees for isolation effects during encoding, distinctiveness effects during recognition, and potential “false memories” generated by the DRM paradigm by presenting a serial recognition memory task. The isolation effect previously reported (Beran, 2011) was not replicated in this experiment. Two of four chimpanzees showed improved recognition performance when information about distinctiveness could be used to exclude incorrect responses. None of the chimpanzees were significantly impaired in the “false memory” condition. However, limitations to this approach are discussed that require caution about assuming identical memory processes in these chimpanzees and in humans. Keywords: chimpanzees, memory, DRM illusion, isolation effect, false memory, distinctiveness, relational processing Research in the 20th century redefined our understanding of ape minds, especially the pioneering work of Dr. -

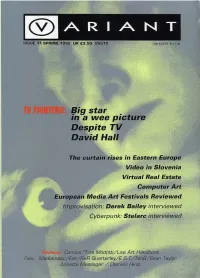

Variant Issue 11 Spring 1992

A R I /K N T ISSUE 11 SPRING 1992 UK £3.50 US$10 CAN $10.95 IRS4.00 mm FIGHTERS Big star in a wee pictur Despite T David Hal The cur ises in Eastern Eu Video in Slovenia Virtual Real Estate Computer Art m>m European Media Art Festivals Reviewed Improvisation: Derek Bailey interviewed Cyberpunk: Stelarc interviewed illii mm »«««<: Comics/Tina Modotti/Live Art Handboo Felix, Mediamatie/Ear/ReR Ouarterley/E. S. T/Ten8/Sean Taylor Annette Messaoer / Damien Hirst EDITORIAL QUOTES 4 Variant is a magazine of cross- NEWS currents in culture: art practice, 6 media, critical ideas, imaginative FESTIVAL and independent tendencies. We CALENDAR are a charitable project and 8 publish four times a year with the REPORT assistance of grants, advertising The Great British Mistake and sales. Most items are com- Vague + Vagabond Reviewed missioned, but we weicome con- 10 tributions and ideas for news items, reviews, articles, inter- DESPITE TV views, and polemical writing. INTERVIEWED BY MALCOLM DICKSON Guidelines for writers are avail- 16 able. We also welcome ideas for MEDIA MOGULS artists pages and for items which we can distribute within the MENTAL POLLUTION magazine, such as stickers, DON COUTTS + STUART COSGROVE prints, xerox work and other INTERVIEWED BY DOUG AUBREY ephemera. VIDEO FROM SLOVENIA Deadline for issue 1 2 is MARINA GRZINIC May 1 5th (Contributions) May 29th (Advertising) 26 THE CURTAIN RISES To advertise call 041 221 6380. ROLAND MILLER Rates for B & and colour W 28 available. FALSE PERSPECTIVES Subscriptions are £14 for four IN VIRTUAL SPACE issues (individuals) £20 for four SEAN CUBITT issues (institutions) 32 MAUSOLEA + ALTARed NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS STATES JEREMY WELSH Doug Aubrey is a freelance video/TV Director Jochen Coldewey is a writer and curator living in 36 Germany.