The Popular Culture Studies Journal Volume 8 Number 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

World Latin American Agenda 2016

World Latin American Agenda 2016 In its category, the Latin American book most widely distributed inside and outside the Americas each year. A sign of continental and global communion among individuals and communities excited by and committed to the Great Causes of the Patria Grande. An Agenda that expresses the hope of the world’s poor from a Latin American perspective. A manual for creating a different kind of globalization. A collection of the historical memories of militancy. An anthology of solidarity and creativity. A pedagogical tool for popular education, communication and social action. From the Great Homeland to the Greater Homeland. Our cover image by Maximino CEREZO BARREDO. See all our history, 25 years long, through our covers, at: latinoamericana.org/digital /desde1992.jpg and through the PDF files, at: latinoamericana.org/digital This year we remind you... We put the accent on vision, on attitude, on awareness, on education... Obviously, we aim at practice. However our “charisma” is to provoke the transformations of awareness necessary so that radically new practices might arise from another systemic vision and not just reforms or patches. We want to ally ourselves with all those who search for that transformation of conscience. We are at its service. This Agenda wants to be, as always and even more than at other times, a box of materials and tools for popular education. latinoamericana.org/2016/info is the web site we have set up on the network in order to offer and circulate more material, ideas and pedagogical resources than can economically be accommo- dated in this paper version. -

Thefeminist Porn Bookintrocha

Introduction: The Politics of Producing Pleasure CONSTANCE PENLEY, CELINE PARREÑAS SHIMIZU, MIREILLE MILLER-YOUNG, and TRISTAN TAORMINO he Feminist Porn Book is the frst collection to bring together writ- ings by feminist porn producers and feminist porn scholars to Tengage, challenge, and re-imagine pornography. As collaborating editors of this volume, we are three porn professors and one porn direc- tor who have had an energetic dialogue about feminist politics and por- nography for years. In their criticism, feminist opponents of porn cast pornography as a monolithic medium and industry and make sweep- ing generalizations about its production, its workers, its consumers, and its efects on society. Tese antiporn feminists respond to feminist por- nographers and feminist porn professors in several ways. Tey accuse us of deceiving ourselves and others about the nature of pornography; they claim we fail to look critically at any porn and hold up all porn as empowering. More typically, they simply dismiss out of hand our abil- ity or authority to make it or study it. But Te Feminist Porn Book ofers arguments, facts, and histories that cannot be summarily rejected, by providing on-the-ground and well-researched accounts of the politics of producing pleasure. Our agenda is twofold: to explore the emergence and signifcance of a thriving feminist porn movement, and to gather some of the best new feminist scholarship on pornography. By putting our voices into conversation, this book sparks new thinking about the richness and complexity of porn as a genre and an industry in a way that helps us to appreciate the work that feminists in the porn industry are doing, both in the mainstream and on its countercultural edges. -

Turns to Affect in Feminist Film Theory 97 Anu Koivunen Sound and Feminist Modernity in Black Women’S Film Narratives 111 Geetha Ramanathan

European Film Studies Mutations and Appropriations in THE KEY DEBATES FEMINISMS Laura Mulvey and 5 Anna Backman Rogers (eds.) Amsterdam University Press Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) -

Feminisms 1..277

Feminisms The Key Debates Mutations and Appropriations in European Film Studies Series Editors Ian Christie, Dominique Chateau, Annie van den Oever Feminisms Diversity, Difference, and Multiplicity in Contemporary Film Cultures Edited by Laura Mulvey and Anna Backman Rogers Amsterdam University Press The publication of this book is made possible by grants from the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO). Cover design: Neon, design and communications | Sabine Mannel Lay-out: japes, Amsterdam Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 676 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 363 4 doi 10.5117/9789089646767 nur 670 © L. Mulvey, A. Backman Rogers / Amsterdam University Press B.V., Amsterdam 2015 All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this book may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the written permission of both the copyright owner and the author of the book. Contents Editorial 9 Preface 10 Acknowledgments 15 Introduction: 1970s Feminist Film Theory and the Obsolescent Object 17 Laura Mulvey PART I New Perspectives: Images and the Female Body Disconnected Heroines, Icy Intelligence: Reframing Feminism(s) and Feminist Identities at the Borders Involving the Isolated Female TV Detective in Scandinavian-Noir 29 Janet McCabe Lena Dunham’s Girls: Can-Do Girls, -

Fitment Chart (Pdf)

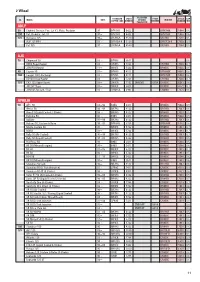

2 Wheel PLATINUM CC MODEL DATE STANDARD STOCK OR GOLD STOCK IRIDIUM STOCK GAP COPPER CORE NUMBER PALLADIUM NUMBER NUMBER MM ADLY 50 Citybird, Crosser, Fox, Jet X1, Pista, Predator 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 100 Cat, Predator, Jet, X1 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 125 Activator 125 99 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJP 125 PR4 03 DPR7EA-9 5129 DPR7EIX-9 7803 0.9 Cat 125 97 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJS 50 Chipmunk 50 03 BP4HS 3611 0.6 DD50 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 JSM 50 Motard 11 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 80 Coyote 80 03 BP6HS 4511 BPR6HIX 4085 0.6 100 Cougar 100 (Jincheng) 03 BP7HS 5111 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 DD100 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 125 CR3-125 Super Sports 08 DR8EA 7162 DR8EVX 6354 DR8EIX 6681 0.6 JS125Y Tiger 03 DR8ES 5423 DR9EIX 4772 0.7 JSM125 Motard / Trail 10 CR6HSA 2983 CR6HIX 7274 0.6 APRILIA 50 AF1 50 8892 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Amico 50 9294 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Area 51 (Liquid Cooled 2-Stroke) 98 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Extrema 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Gulliver 9799 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Habana 50, Custom & Retro 9905 BPR8HS 3725 BPR8HIX 6742 0.6 Mojito Custom 50 05 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 MX50 03 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 Rally 50 (Air Cooled) 9599 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.7 Rally 50 (Liquid Cooled) 9703 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Red Rose 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 RS 50 (Minarelli engine) 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 RS 50 0105 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 RS 50 06 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.5 RS4 50 1113 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 ‡ Early Ducati Testastretta bikes (749, 998, 999 models) can have very little clearance between the plug hex and the RX 50 (Minarelli engine) 97 B9ES 2611 BR9EIX 3981 0.6 cylinder head that may require a thin walled socket, no larger than 20.5mm OD to allow the plug to be fitted. -

Stockholm Cinema Studies 11

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS STOCKHOLMIENSIS Stockholm Cinema Studies 11 Imagining Safe Space The Politics of Queer, Feminist and Lesbian Pornography Ingrid Ryberg This is a print on demand publication distributed by Stockholm University Library www.sub.su.se First issue printed by US-AB 2012 ©Ingrid Ryberg and Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis 2012 ISSN 1653-4859 ISBN 978-91-86071-83-7 Publisher: Acta Universitatis Stockholmiensis, Stockholm Distributor: Stockholm University Library, Sweden Printed 2012 by US-AB Cover image: Still from Phone Fuck (Ingrid Ryberg, 2009) Contents 1. Introduction ................................................................................................... 13 Research aims and questions .................................................................................... 13 Queer, feminist and lesbian porn film culture: central debates.................................... 19 Feminism and/vs. pornography ............................................................................. 20 What is queer, feminist and lesbian pornography?................................................ 25 The sexualized public sphere................................................................................ 27 Interpretive community as a key concept and theoretical framework.......................... 30 Spectatorial practices and historical context.......................................................... 33 Porn studies .......................................................................................................... 35 Embodied -

Supreme Court of the State of New York County of New York ______

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK __________________________________________________ In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, MEMORANDUM OF Petitioner, LAW IN SUPPORT OF -against- PETITION FOR HABEAS CORPUS CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. Index No. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents. __________________________________________________ Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5 Dunhill Road New Hyde Park, NY 11040 Phone (516) 747-4726 Steven M. Wise, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5195 NW 112th Terrace Coral Springs, FL 33076 Phone (954) 648-9864 Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. Subject to pro hac vice admission January_____, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................................ v I. SUMMARY OF NEW GROUNDS AND FACTS NEITHER PRESENTED NOR DETERMINED IN NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., EX REL. KIKO v. PRESTI OR NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC. ON BEHALF OF TOMMY v. LAVERY. ............................................................................................................. 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................... 6 III. STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................... -

Human Uniqueness in the Age of Ape Language Research1

Society and Animals 18 (2010) 397-412 brill.nl/soan Human Uniqueness in the Age of Ape Language Research1 Mary Trachsel University of Iowa [email protected] Abstract This paper summarizes the debate on human uniqueness launched by Charles Darwin’s publi- cation of The Origin of Species in 1859. In the progress of this debate, Noam Chomsky’s intro- duction of the Language-Acquisition Device (LAD) in the mid-1960s marked a turn to the machine model of mind that seeks human uniqueness in uniquely human components of neu- ral circuitry. A subsequent divergence from the machine model can be traced in the short his- tory of ape language research (ALR). In the past fifty years, the focus of ALR has shifted from the search for behavioral evidence of syntax in the minds of individual apes to participant- observation of coregulated interactions between humans and nonhuman apes. Rejecting the computational machine model of mind, the laboratory methodologies of ALR scientists Tetsuro Matsuzawa and Sue Savage-Rumbaugh represent a worldview coherent with Darwin’s continu- ity hypothesis. Keywords ape language research, artificial intelligence, Chomsky, comparative psychology, Darwin, human uniqueness, social cognition Introduction Nothing at first can appear more difficult to believe than that the more complex organs and instincts should have been perfected, not by means superior to, though analogous with, human reason, but by the accumulation of innumerable slight variations, each good for the individual possessor. (Darwin, 1989b, p. 421) With the publication of The Origin of Species (1859/1989a), Charles Darwin steered science directly into a conversation about human uniqueness previ- ously dominated by religion and philosophy. -

The Humanities and Posthumanism

english edition 1 2015 The Humanities and Posthumanism issue editor GRZEGORZ GROCHOWSKI MICHAł PAWEł MARKOWSKI Humanities: an Unfinished Project E WA DOMAńSKA Ecological Humanities R YSZARD NYCZ Towards Innovative Humanities: The Text as a Laboratory. Traditions, Hypotheses, Ideas O LGA CIELEMęCKA Angelus Novus Looks to the Future. On the Anti-Humanism Which Overcomes Nothingness SYZ MON WRÓBEL Domesticating Animals: A Description of a Certain Disturbance teksty drugie · Institute of Literary Research Polish Academy of Science index 337412 · pl issn 0867-0633 EDITORIAL BOARD Agata Bielik-Robson (uk), Włodzimierz Bolecki, Maria Delaperrière (France), Ewa Domańska, Grzegorz Grochowski, Zdzisław Łapiński, Michał Paweł Markowski (usa), Maciej Maryl, Jakub Momro, Anna Nasiłowska (Deputy Editor-in-Chief), Leonard Neuger (Sweden), Ryszard Nycz (Editor-in-Chief), Bożena Shallcross (usa), Marta Zielińska, Tul’si Bhambry (English Translator and Language Consultant), Justyna Tabaszewska, Marta Bukowiecka (Managing Editor) ADVISORY BOARD Edward Balcerzan, Stanisław Barańczak (usa) , Małgorzata Czermińska, Paweł Dybel, Knut Andreas Grimstad (Norway), Jerzy Jarzębski, Bożena Karwowska (Canada), Krzysztof Kłosiński, Dorota Krawczyńska, Vladimir Krysinski (Canada), Luigi Marinelli (Italy ), Arent van Nieukerken (Holland), Ewa Rewers, German Ritz (Switzerland), Henryk Siewierski (Brasil), Janusz Sławiński , Ewa Thompson (usa), Joanna Tokarska-Bakir, Tamara Trojanowska (Canada), Alois Woldan (Austria), Anna Zeidler-Janiszewska ADDRESS Nowy Świat 72, room. -

In Pursuit of Magic Vol 1 / Issue 2 / July 2021 Dear Readers

community writing project journal vol 1 / issue 2 / July 2021 in pursuit of magic vol 1 / issue 2 / July 2021 Dear Readers As one of my favorite blues singer, Etta James delivered, “At Last,” we are ready with Issue #2 of the Community Writing Project Journal. The overwhelming response to our submis- sion call was delightful. Thank to all of you who gave generously with words and art. Special recognition to ArtSpeak/From Page to Performance participants who continue to regularly submit and support our efforts. A super special thanks to Marcia Klein, Grant Ex- plorer for the CWPJ. She pointed us in the direction of Arts Westchester. All writ- golda Solomon co-editor ers from our premiere issue will be represented in their Spring Exhibition -projects that were initiated during the pandemic. This issue is dedicated to my colleague at Borough of Man- hattan Community College Robert Lapides my first editor, who recently passed away. He saw my potential. “You can talk Golda; how about writing down some of your stories.” I am still talking and writing. Cover art: In Pursuit of Magic (2020) We are proud to introduce a new section, ‘Kidz Roar/Raw, Ysabella Hincapie-Gara unedited contributions from young writers and artists. Our youngest writer is 14 and our youngest artist, four. Editors: Golda Solomon & Jacqueline Reason Artspeak/From Page to Performance Karim Ahmed: Technical Assistant Enjoy our labor of love, Artspeak/From Page to Performance lead a supportive community of Marcia Klein: Grant Hunter meets of each monthly on 2nd writers in exploring poetry, music golda Michele Amaro: Blue Door Art Center Gallery Director Saturdays. -

Kiswahili for Foreigners ( Pdfdrive.Com ) (1).Pdf

KISWAHILI FOR FOREIGNERS By AMIR. A. MOHAMED FIRST EDITION 1993 SECOND EDITION 2000 THIRD EDITION 2009 © Create Space 0f Amazon.com CONTENTS – YALIYOMO Page FOREWORD Ukurasa I INTRODUCTION – 1 KITANGULIZI II THE SOUND 2 SYSTEM III ROOTS, STEMS, 3 AFFIXES IV NOUNS AND 4 CLASSIFICATION V VERB AND THEIR 11 TENSES VI COMPOUND 16 TENSES VII PRONOUNS 17 VIII ADJECTIVES 22 X ADVERBS 25 XI PREPOSITONS 29 AND CONJUCTIONS XII VOBABULARY – 33 MSAMIATI XIII KISWAHILI 46 SAYING – MISEMO YA KISWAHILI XIV EXERCISE – 52 MZOESI XV KISWAHILI WORD 65 – 124 POWER IX KISWAHILI SLANGS & BOMBASTCS – SIMO ZA KISWAHILI 125-174 IIX BIBLIOGRAPHY FOREWORD Kiswahili*is a growing language in Africa and the world as a whole. There are historians who believe that Kiswahili is probably nine hundred years old and like other languages, its significance can be proved by the growing demand of its usage and the constant increase in the world of the need to learn and to speak Kiswahili. The world is entering into the new millennium and we are all striving to have a better life and a peaceful world. Therefore, it has now become increasingly necessary for foreigners to learn Kiswahili no matter what they do and no matter where they are. Besides the social and economic dimensions of the language abroad like working in East Africa or just on holidays, learning the language may help to improve the race relations between Africans and foreigners. It’s time to learn to understand each other and to know how to make perfect moves in our lives. History of the language reveals that Kiswahili is of Bantu origin but heavily loaded with Arabic, English, Indian and other oriental words. -

Andrews Tove.Pdf (1.498Mb)

MASTEROPPGAVE Project Sci-fi: I n v i t i n g a l i e n s a n d r o b o t s i n t o t h e E n g l i s h c l a s s r o o m , h o w f i c t i o n a l c u l t u r e s c a n p r o m o t e d e v e l o p m e n t o f i n t e r c u l t u r a l c o m p e t e n c e Tove Lora Andrews 06.11.2019 Master Fremmedspråk i skolen Avdeling for økonomi, språk og samfunsdag Abstract Little focus has been placed on why English teachers in Norway should favour intercultural competence over cultural facts. Yet knowing cultural facts do not make pupils effective communicators, which is the purpose for language learning. Intercultural competence prepares pupils for intercultural encounters, through a conglomeration of open attitudes, accurate knowledge, insightful understanding, appropriate skills, and practical application. Literature is a common and efficient means of exploring culture and intercultural encounters within a classroom setting. Both multicultural literature and science fiction explore cultural themes and identity, but the latter explores a broader range of contemporary topics. Therefore, this thesis sought to explore to what extent science fiction could be used to promote intercultural competence in the English classroom. Analysing fiction and imaginary cultures circumvented pitfalls common to multicultural literature.