A New Perspective on the Mating Strategies of Chimpanzees

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Gorilla Beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26

Gorilla beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia ChordataMammaliaPrimatesHominidae Scientific Gorilla beringei Name: Species Matschie, 1903 Authority: Infra- specific See Gorilla beringei ssp. beringei Taxa See Gorilla beringei ssp. graueri Assessed: Common Name(s): English –Eastern Gorilla French –Gorille de l'Est Spanish–Gorilla Oriental TaxonomicMittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B. and Wilson D.E. 2013. Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume Source(s): 3 Primates. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. This species appeared in the 1996 Red List as a subspecies of Gorilla gorilla. Since 2001, the Eastern Taxonomic Gorilla has been considered a separate species (Gorilla beringei) with two subspecies: Grauer’s Gorilla Notes: (Gorilla beringei graueri) and the Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) following Groves (2001). Assessment Information [top] Red List Category & Criteria: Critically Endangered A4bcd ver 3.1 Year Published: 2016 Date Assessed: 2016-04-01 Assessor(s): Plumptre, A., Robbins, M. & Williamson, E.A. Reviewer(s): Mittermeier, R.A. & Rylands, A.B. Contributor(s): Butynski, T.M. & Gray, M. Justification: Eastern Gorillas (Gorilla beringei) live in the mountainous forests of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, northwest Rwanda and southwest Uganda. This region was the epicentre of Africa's "world war", to which Gorillas have also fallen victim. The Mountain Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei beringei), has been listed as Critically Endangered since 1996. Although a drastic reduction of the Grauer’s Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei graueri), has long been suspected, quantitative evidence of the decline has been lacking (Robbins and Williamson 2008). During the past 20 years, Grauer’s Gorillas have been severely affected by human activities, most notably poaching for bushmeat associated with artisanal mining camps and for commercial trade (Plumptre et al. -

Surrogate Motherhood

Surrogate Motherhood Page ii MEDICAL ETHICS SERIES David H. Smith and Robert M. Veatch, Editors Page iii Surrogate Motherhood Politics and Privacy Edited by Larry Gostin Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis Page iv This book is based on a special issue of Law, Medicine & Health Care (16:1–2, spring/summer, 1988), a journal of the American Society of Law & Medicine. Many of the essays have been revised, updated, or corrected, and five appendices have been added. ASLM coordinator of book production was Merrill Kaitz. © 1988, 1990 American Society of Law & Medicine All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permission constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1984. Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Surrogate motherhood : politics and privacy / edited by Larry Gostin. p. cm. — (Medical ethics series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0253326044 (alk. paper) 1. Surrogate mothers—Legal status, laws, etc.—United States. 2. Surrogate mothers—Civil rights—United States. 3. Surrogate mothers—United States. I. Gostin, Larry O. (Larry Ogalthorpe) II. Series. KF540.A75S87 1990 346.7301'7—dc20 [347.30617] 8945474 CIP 1 2 3 4 5 94 93 92 91 90 Page v Contents Introduction ix Larry Gostin CIVIL LIBERTIES A Civil Liberties Analysis of Surrogacy Arrangements 3 Larry Gostin Procreative Liberty and the State's Burden of Proof in Regulating Noncoital 24 Reproduction John A. -

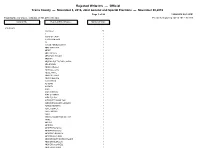

Rejected Write-Ins

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

Himpanzee C Chronicle

An Exclusive Publication Produced By Chimp Haven, Inc. VOLUME IX ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2009 HIMPANZEE www.chimphaven.org C CHRONICLE INSIDE THIS ISSUE: PET CHIMPANZEES HAVE BEEN IN THE NEWS THIS YEAR. Travis, who attacked a woman in Connecticut, was shot to death. Timmie was shot in Missouri when he escaped and attacked a deputy. There are countless more pet chimpanzees living in private homes throughout the United States. This edition of the Chimpanzee Chronicle discusses this serious issue. Please share it with others. WHY CHIMPANZEES DON’T MAKE GOOD PETS By Linda Brent, PhD, President and Director When chimpanzees become pets, the outcome for them or their human “family” is rarely a good one. Chimpanzees are large, wild animals who are highly intelligent and require a great deal of socialization with their mother and other chimpanzees. Sanctuaries most often hear about pet chimpanzees when they reach adolescence and are too difficult to manage any longer. Often, they bite someone or break household items. Sometimes they get loose or seriously attack a person. Generally speaking, these actions are part of normal chimpanzee behavior. An adolescent male chimpanzee begins to try to dominate others as he works his way up the dominance hierarchy or social ladder. He does this by BOARD OF displaying, hitting and throwing objects, and sometimes attacking others. Pet chimpanzees do not have the benefit of a normal social group as an outlet for their behavior, and often these DIRECTORS behaviors are directed at human caregivers or strangers. Since chimpanzees can easily weigh as much as a person—but are far stronger—they are obviously dangerous animals to have in the Thomas Butler, D.V.M., M.S. -

Supreme Court of the State of New York County of New York ______

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK __________________________________________________ In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, MEMORANDUM OF Petitioner, LAW IN SUPPORT OF -against- PETITION FOR HABEAS CORPUS CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. Index No. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents. __________________________________________________ Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5 Dunhill Road New Hyde Park, NY 11040 Phone (516) 747-4726 Steven M. Wise, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5195 NW 112th Terrace Coral Springs, FL 33076 Phone (954) 648-9864 Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. Subject to pro hac vice admission January_____, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................................ v I. SUMMARY OF NEW GROUNDS AND FACTS NEITHER PRESENTED NOR DETERMINED IN NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., EX REL. KIKO v. PRESTI OR NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC. ON BEHALF OF TOMMY v. LAVERY. ............................................................................................................. 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................... 6 III. STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................... -

Epidemiology and Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium Spp. in Humans, Wild Primates, and Domesticated Animals in the Greater Gombe Ecosystem, Tanzania

RESEARCH ARTICLE Epidemiology and Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in Humans, Wild Primates, and Domesticated Animals in the Greater Gombe Ecosystem, Tanzania Michele B. Parsons1,2, Dominic Travis3, Elizabeth V. Lonsdorf4, Iddi Lipende5 Dawn M. Anthony Roellig2,5, Shadrack Kamenya5, Hongwei Zhang6, Lihua Xiao2 Thomas R. Gillespie1* 1 Program in Population Biology, Ecology, and Evolution and Departments of Environmental Sciences and Environmental Health, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, 2 Division of Foodborne, Waterborne, and Environmental Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America, 3 College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, Minnesota, United States of America, 4 Department of Psychology, Franklin and Marshall College, Lancaster, Pennsylvania, United States of America, 5 The Jane Goodall Institute, Kigoma, Tanzania, OPEN ACCESS 6 Institute of Parasite Disease Prevention and Control, Henan Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Zhengzhou, China Citation: Parsons MB, Travis D, Lonsdorf EV, Lipende I, Roellig DMA, Kamenya S, et al. (2015) * [email protected] Epidemiology and Molecular Characterization of Cryptosporidium spp. in Humans, Wild Primates, and Domesticated Animals in the Greater Gombe Ecosystem, Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 10(2): Abstract e0003529. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0003529 Cryptosporidium is an important zoonotic parasite globally. Few studies have examined the Editor: Stephen Baker, Oxford University Clinical ecology and epidemiology of this pathogen in rural tropical systems characterized by high Research Unit, VIETNAM rates of overlap among humans, domesticated animals, and wildlife. We investigated risk Received: October 31, 2014 factors for Cryptosporidium infection and assessed cross-species transmission potential Accepted: January 9, 2015 among people, non-human primates, and domestic animals in the Gombe Ecosystem, Published: February 20, 2015 Kigoma District, Tanzania. -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Beyond Anthropomorphism (Sue Savage

stone age institute publication series Series Editors Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth Stone Age Institute Gosport, Indiana and Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana Number 1. THE OLDOWAN: Case Studies into the Earliest Stone Age Nicholas Toth and Kathy Schick, editors Number 2. BREATHING LIFE INTO FOSSILS: Taphonomic Studies in Honor of C.K. (Bob) Brain Travis Rayne Pickering, Kathy Schick, and Nicholas Toth, editors Number 3. THE CUTTING EDGE: New Approaches to the Archaeology of Human Origins Kathy Schick, and Nicholas Toth, editors Number 4. THE HUMAN BRAIN EVOLVING: Paleoneurological Studies in Honor of Ralph L. Holloway Douglas Broadfield, Michael Yuan, Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth, editors STONE AGE INSTITUTE PUBLICATION SERIES NUMBER 1 THE OLDOWAN: Case Studies Into the Earliest Stone Age Edited by Nicholas Toth and Kathy Schick Stone Age Institute Press · www.stoneageinstitute.org 1392 W. Dittemore Road · Gosport, IN 47433 COVER PHOTOS Front, clockwise from upper left: 1) Excavation at Ain Hanech, Algeria (courtesy of Mohamed Sahnouni). 2) Kanzi, a bonobo (‘pygmy chimpanzee’) fl akes a chopper-core by hard-hammer percussion (courtesy Great Ape Trust). 3) Experimental Oldowan fl aking (Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth). 4) Scanning electron micrograph of prehistoric cut-marks from a stone tool on a mammal limb shaft fragment (Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth). 5) Kinesiological data from Oldowan fl aking (courtesy of Jesus Dapena). 6) Positron emission tomography of brain activity during Oldowan fl aking (courtesy of Dietrich Stout). 7) Experimental processing of elephant carcass with Oldowan fl akes (the animal died of natural causes). (Kathy Schick and Nicholas Toth). 8) Reconstructed cranium of Australopithecus garhi. -

The Ecological Role of the Bonobo: Seed Dispersal Service in Congo Forests

The ecological role of the Bonobo : seed dispersal service in Congo forests David Beaune To cite this version: David Beaune. The ecological role of the Bonobo : seed dispersal service in Congo forests. Agricultural sciences. Université de Bourgogne, 2012. English. NNT : 2012DIJOS096. tel-00932505 HAL Id: tel-00932505 https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00932505 Submitted on 17 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. UNIVERSITE DE BOURGOGNE UFR Sciences de la Vie, de la Terre et de l'Environnement THÈSE Pour obtenir le grade de Docteur de l’Université de Bourgogne Discipline : Sciences Vie par David Beaune le 28 novembre 2012 The Ecological Role of the Bonobo Seed dispersal service in Congo forests Directeurs de thèse Pr Loïc Bollache, uB Pr François Bretagnolle, uB Dr Barbara Fruth, MPI Jury Bollache, Loïc Prof. Université de Bourgogne Directeur Bretagnolle, François Prof. Université de Bourgogne Directeur Hart, John Dr. Lukuru Research Fundation Rapporteur Krief, Sabrina Dr. MNHN Paris Examinateur McKey, Doyle Prof. Université de Montpellier Rapporteur © Aux jardiniers des forêts. Puissent-ils encore vivre… tout simplement 1 Remerciements Financeurs : Le projet « Rôle écologique des bonobos » a bénéficié de diverses sources de financements : . -

CALL NUM SUBTYPE Author/Artist TITLE B Gr Biography Billy Graham God's Ambassador B Sc Biography Allen, Tom Closer Look at Dr

CALL_NUM SUBTYPE Author/Artist TITLE B Gr Biography Billy Graham God's Ambassador B Sc Biography Allen, Tom Closer Look at Dr. Laura, A B Hu Biography Anders, Isabel Standing on High Places B An Biography Andrew, Brother God's Smuggler Arial, Dan & Heckler- Feltz, B Ca Biography Carpenter's Apprentice, The Cheryl YB Mu Biography Bailey, Faith Coxe George Mueller B Lu Biography Bainton, Roland H. Here I Stand: A Life of Martin Luther B Ba Biography Bakker, Jay Son of a Preacher Man B Le Biography Barratt, David C. S. Lewis and his World B Be Biography Beaner, Lisa Let's Roll B Be Biography Beckingham, Paul M. Walking Towards Hope B Be Biography Belz, Mindy They Say We Are Infidels B Fl Biography Bingham, Rowland V. Making of the Beautiful, The B McP Biography Blumhofer, Edith L. Everybody's Sister: Aimee Semple McPherson B Bo Biography Bowman, Robert God of Wonders B Br Biography Brand, Dr. Margaret E. Vision for God B Br Biography Briscoe, Jill Thank You for Being a Friend B Br Biography Brown, Joan Winmill No Longer Alone B Br Biography Brown, Liane I. Refuge B Bu Biography Buntain, H. Treasures in Heaven B Bu Biography Bunyan, John Grace Abounding to the Chief of Sinners B Bu Biography Burke, Tim & Christine Major League Dad B Bu Biography Burnham, Gracia In the Presence of my Enemies B Bu Biography Burnham, Gracia To Fly Again B Bu Biography Burnham, Vera Green in Winter B Bu Biography Burpo, Todd Heaven is for Real B Do Biography Buss, Dale Family Man B Bu Biography Butler, Brett Field of Hope B Bu Biography Butterfield, Rosaria Secret -

PETITION Before the Fish and Wildlife Service United States Department

PETITION Before the Fish and Wildlife Service United States Department of the Interior March 16, 2010 To Upgrade Captive Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) from Threatened to Endangered Status Pursuant to the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as Amended Pan troglodytes (Photograph by National Geographic) Prepared by Anna Frostic, Esq. The Humane Society of the United States TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction………………………………………………….…….……….…........4 II. Legal Background………………….…………….………………………………...7 A. Endangered Species Act Background…..…………………………………...7 B. The Listing History of the Chimpanzee……..….…………………………15 III. Argument: Depriving Captive Chimpanzees of Full Protection Under the ESA is Antithetical to Conserving the Species……….………….….……….20 A. The ―Split-Listing‖ Scheme for Pan troglodytes has Contributed to a Proliferation of Privately Owned and Exploited Chimpanzees, Interfering With Conservation of the Species in the Wild..…………....27 1. Chimpanzees in Entertainment.…………………..……..…………....29 a. Chimpanzees Are Widely Exploited for Entertainment in the U.S…………………………………………………………………..29 b. Because Chimpanzees Are So Pervasively Used in Entertainment the Public Believes the Species is Prevalent in the Wild………………………………………………………....69 c. Chimpanzees Used in Entertainment Are Abused and Mistreated................................................................................71 2. Chimpanzees Used as Pets……………………………………………...77 3. Chimpanzees in Biomedical Research Laboratories………..…........87 B. Threats to Wild Chimpanzee Populations Have Only Increased