Pan Paniscus, Bonobo

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan Paniscus)

EAZA Best Practice Guidelines Bonobo (Pan paniscus) Editors: Dr Jeroen Stevens Contact information: Royal Zoological Society of Antwerp – K. Astridplein 26 – B 2018 Antwerp, Belgium Email: [email protected] Name of TAG: Great Ape TAG TAG Chair: Dr. María Teresa Abelló Poveda – Barcelona Zoo [email protected] Edition: First edition - 2020 1 2 EAZA Best Practice Guidelines disclaimer Copyright (February 2020) by EAZA Executive Office, Amsterdam. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in hard copy, machine-readable or other forms without advance written permission from the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA). Members of the European Association of Zoos and Aquaria (EAZA) may copy this information for their own use as needed. The information contained in these EAZA Best Practice Guidelines has been obtained from numerous sources believed to be reliable. EAZA and the EAZA APE TAG make a diligent effort to provide a complete and accurate representation of the data in its reports, publications, and services. However, EAZA does not guarantee the accuracy, adequacy, or completeness of any information. EAZA disclaims all liability for errors or omissions that may exist and shall not be liable for any incidental, consequential, or other damages (whether resulting from negligence or otherwise) including, without limitation, exemplary damages or lost profits arising out of or in connection with the use of this publication. Because the technical information provided in the EAZA Best Practice Guidelines can easily be misread or misinterpreted unless properly analysed, EAZA strongly recommends that users of this information consult with the editors in all matters related to data analysis and interpretation. -

Gorilla Beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26

Gorilla beringei (Eastern Gorilla) 07/09/2016, 02:26 Kingdom Phylum Class Order Family Animalia ChordataMammaliaPrimatesHominidae Scientific Gorilla beringei Name: Species Matschie, 1903 Authority: Infra- specific See Gorilla beringei ssp. beringei Taxa See Gorilla beringei ssp. graueri Assessed: Common Name(s): English –Eastern Gorilla French –Gorille de l'Est Spanish–Gorilla Oriental TaxonomicMittermeier, R.A., Rylands, A.B. and Wilson D.E. 2013. Handbook of the Mammals of the World: Volume Source(s): 3 Primates. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. This species appeared in the 1996 Red List as a subspecies of Gorilla gorilla. Since 2001, the Eastern Taxonomic Gorilla has been considered a separate species (Gorilla beringei) with two subspecies: Grauer’s Gorilla Notes: (Gorilla beringei graueri) and the Mountain Gorilla (Gorilla beringei beringei) following Groves (2001). Assessment Information [top] Red List Category & Criteria: Critically Endangered A4bcd ver 3.1 Year Published: 2016 Date Assessed: 2016-04-01 Assessor(s): Plumptre, A., Robbins, M. & Williamson, E.A. Reviewer(s): Mittermeier, R.A. & Rylands, A.B. Contributor(s): Butynski, T.M. & Gray, M. Justification: Eastern Gorillas (Gorilla beringei) live in the mountainous forests of eastern Democratic Republic of Congo, northwest Rwanda and southwest Uganda. This region was the epicentre of Africa's "world war", to which Gorillas have also fallen victim. The Mountain Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei beringei), has been listed as Critically Endangered since 1996. Although a drastic reduction of the Grauer’s Gorilla subspecies (Gorilla beringei graueri), has long been suspected, quantitative evidence of the decline has been lacking (Robbins and Williamson 2008). During the past 20 years, Grauer’s Gorillas have been severely affected by human activities, most notably poaching for bushmeat associated with artisanal mining camps and for commercial trade (Plumptre et al. -

Bonobos (Pan Paniscus) Show an Attentional Bias Toward Conspecifics’ Emotions

Bonobos (Pan paniscus) show an attentional bias toward conspecifics’ emotions Mariska E. Kreta,1, Linda Jaasmab, Thomas Biondac, and Jasper G. Wijnend aInstitute of Psychology, Cognitive Psychology Unit, Leiden University, 2333 AK Leiden, The Netherlands; bLeiden Institute for Brain and Cognition, 2300 RC Leiden, The Netherlands; cApenheul Primate Park, 7313 HK Apeldoorn, The Netherlands; and dPsychology Department, University of Amsterdam, 1018 XA Amsterdam, The Netherlands Edited by Susan T. Fiske, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, and approved February 2, 2016 (received for review November 8, 2015) In social animals, the fast detection of group members’ emotional perspective, it is most adaptive to be able to quickly attend to rel- expressions promotes swift and adequate responses, which is cru- evant stimuli, whether those are threats in the environment or an cial for the maintenance of social bonds and ultimately for group affiliative signal from an individual who could provide support and survival. The dot-probe task is a well-established paradigm in psy- care (24, 25). chology, measuring emotional attention through reaction times. Most primates spend their lives in social groups. To prevent Humans tend to be biased toward emotional images, especially conflicts, they keep close track of others’ behaviors, emotions, and when the emotion is of a threatening nature. Bonobos have rich, social debts. For example, chimpanzees remember who groomed social emotional lives and are known for their soft and friendly char- whom for long periods of time (26). In the chimpanzee, but also in acter. In the present study, we investigated (i) whether bonobos, the rarely studied bonobo, grooming is a major social activity and similar to humans, have an attentional bias toward emotional scenes a means by which animals living in proximity may bond and re- ii compared with conspecifics showing a neutral expression, and ( ) inforce social structures. -

Orangutan…Taxonomy…And…Nomenclature

«««« ORANGUTAN…TAXONOMY…AND…NOMENCLATURE« « Craig«D em itros« « The«taxonom y«of«the«orangutan«has«been«confusing«and«is«still«the«subject«of« m uch«debate.«Q uestions«at«the«specific«and«subspecific«level«are«still«being« investigated«(Courtenay«et«al.«1988).«The«follow ing«taxonom ic«inform ation«is« taken«prim arily«from «G roves,«1971.« « H IG H ER«LEVEL«TAXO N O M Y:« O rder:«Prim ates« Suborder:«A nthropoidea« Superfam ily:«H om inoidea« Fam ily:«Pongidae«(Includes«extant«genera«Pan,…Gorilla…and…Pongo).« « H ISTO RICA L«TAXO N O M Y«AT«TH E«G EN U S«A N D «G EN U S«SPECIES«LEVEL:«« G enus« Pongo«Lacepede,«1799.« O urangus«Zim m erm an,«1777«(N am e«invalidated).« « G enus«species«(Pongo…pygm aeus«H oppius,«1763).« Sim ia…pygm aeus«H oppius,«1763.««Type«locality«Sum atra.« Sim ia…satyrus«Linnaeus,«1766.« O urangus…outangus«Zim m erm an,«1777.« Pongo…borneo«Lacepede,«1799.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Sim ia…Agrais«Schreber,«1779.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Pongo…W urm bii«Tiedem ann,«1808.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Pongo…Abelii«Lesson,«1827.««Type«locality«Sum atra.« Sim ia…M orio«O w en,«1836.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Pithecus…bicolor«I.«G eoffroy,«1841.««Type«locality«Sum atra.« Sim ia…Gargantica«Pearson,«1841.««Type«locality«Sum atra.« Pithecus…brookei«Blyth,«1853.««Type«locality«Saraw ak.« Pithecus…ow enii«Blyth,«1853.««Type«locality«Saraw ak.« Pithecus…curtus«Blyth,«1855.««Type«locality«Saraw ak.« Satyrus…Knekias«M eyer,«1856.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Pithecus…W allichii«G ray,«1870.««Type«locality«Borneo.« Pithecus…sum atranus«Selenka,«1896.««Type«locality«Sum atra.« Pongo…pygm aeus«Rothschild,«1904.««First«use«of«this«com bination.« Ptihecus…w allacei«Elliot,«1913.««Type«locality«Borneo.« « CURRENT…TAXONOMY« « The«current«and«m ost«accepted«taxonom y«of«the«G enus«Pongo«includes«one« species«Pongo…pygm aeus«and«tw o«subspecies«P.p.…pygm aeus«(the«Bornean« subspecies)«and«P.p.…abelii«(the«Sum atran«subspecies)«(Bem m el«1968;«Jones« 1969;«G roves«1971;«Jacobshagen«1979;«Seuarez«et«al.«1979«and«G roves«1993).« 5« « . -

Cross-River Gorillas

CMS Agreement on the Distribution: General Conservation of Gorillas UNEP/GA/MOP3/Inf.9 and their Habitats of the 24 April 2019 Convention on Migratory Species Original: English THIRD MEETING OF THE PARTIES Entebbe, Uganda, 18-20 June 2019 REVISED REGIONAL ACTION PLAN FOR THE CONSERVATION OF THE CROSS RIVER GORILLA (Gorilla gorilla diehli) 2014 - 2019 For reasons of economy, this document is printed in a limited number, and will not be distributed at the meeting. Delegates are kindly requested to bring their copy to the meeting and not to request additional copies. FewerToday, thethan total population of Cross River gorillas may number fewer than 300 individuals 300 left Revised Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) 2014–2019 HopeUnderstanding the status of the changing threats across the Cross River gorilla landscape will provide key information for guiding our collectiveSurvival conservation activities cross river gorilla action plan cover_2013.indd 1 2/3/14 10:27 AM Camera trap image of a Cross River gorilla at Afi Mountain Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) This plan outlines measures that should ensure that Cross River gorilla numbers are able to increase at key core sites, allowing them to extend into areas where they have been absent for many years. cross river gorilla action plan cover_2013.indd 2 2/3/14 10:27 AM Revised Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) 2014-2019 Revised Regional Action Plan for the Conservation of the Cross River Gorilla (Gorilla gorilla diehli) 2014-2019 Compiled and edited by Andrew Dunn1, 16, Richard Bergl2, 16, Dirck Byler3, Samuel Eben-Ebai4, Denis Ndeloh Etiendem5, Roger Fotso6, Romanus Ikfuingei6, Inaoyom Imong1, 7, 16, Chris Jameson6, Liz Macfie8, 16, Bethan Mor- gan9, 16, Anthony Nchanji6, Aaron Nicholas10, Louis Nkembi11, Fidelis Omeni12, John Oates13, 16, Amy Pokemp- ner14, Sarah Sawyer15 and Elizabeth A. -

Congolius, a New Genus of African Reed Frog Endemic to The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Congolius, a new genus of African reed frog endemic to the central Congo: A potential case of convergent evolution Tadeáš Nečas1,2*, Gabriel Badjedjea3, Michal Vopálenský4 & Václav Gvoždík1,5* The reed frog genus Hyperolius (Afrobatrachia, Hyperoliidae) is a speciose genus containing over 140 species of mostly small to medium-sized frogs distributed in sub-Saharan Africa. Its high level of colour polymorphism, together with in anurans relatively rare sexual dichromatism, make systematic studies more difcult. As a result, the knowledge of the diversity and taxonomy of this genus is still limited. Hyperolius robustus known only from a handful of localities in rain forests of the central Congo Basin is one of the least known species. Here, we have used molecular methods for the frst time to study the phylogenetic position of this taxon, accompanied by an analysis of phenotype based on external (morphometric) and internal (osteological) morphological characters. Our phylogenetic results undoubtedly placed H. robustus out of Hyperolius into a common clade with sympatric Cryptothylax and West African Morerella. To prevent the uncovered paraphyly, we place H. robustus into a new genus, Congolius. The review of all available data suggests that the new genus is endemic to the central Congolian lowland rain forests. The analysis of phenotype underlined morphological similarity of the new genus to some Hyperolius species. This uniformity of body shape (including cranial shape) indicates that the two genera have either retained ancestral morphology or evolved through convergent evolution under similar ecological pressures in the African rain forests. African reed frogs, Hyperoliidae Laurent, 1943, are presently encompassing almost 230 species in 17 genera. -

Surrogate Motherhood

Surrogate Motherhood Page ii MEDICAL ETHICS SERIES David H. Smith and Robert M. Veatch, Editors Page iii Surrogate Motherhood Politics and Privacy Edited by Larry Gostin Indiana University Press Bloomington and Indianapolis Page iv This book is based on a special issue of Law, Medicine & Health Care (16:1–2, spring/summer, 1988), a journal of the American Society of Law & Medicine. Many of the essays have been revised, updated, or corrected, and five appendices have been added. ASLM coordinator of book production was Merrill Kaitz. © 1988, 1990 American Society of Law & Medicine All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. The Association of American University Presses' Resolution on Permission constitutes the only exception to this prohibition. Manufactured in the United States of America ™ The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences— Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48–1984. Library of Congress CataloginginPublication Data Surrogate motherhood : politics and privacy / edited by Larry Gostin. p. cm. — (Medical ethics series) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0253326044 (alk. paper) 1. Surrogate mothers—Legal status, laws, etc.—United States. 2. Surrogate mothers—Civil rights—United States. 3. Surrogate mothers—United States. I. Gostin, Larry O. (Larry Ogalthorpe) II. Series. KF540.A75S87 1990 346.7301'7—dc20 [347.30617] 8945474 CIP 1 2 3 4 5 94 93 92 91 90 Page v Contents Introduction ix Larry Gostin CIVIL LIBERTIES A Civil Liberties Analysis of Surrogacy Arrangements 3 Larry Gostin Procreative Liberty and the State's Burden of Proof in Regulating Noncoital 24 Reproduction John A. -

Rejected Write-Ins

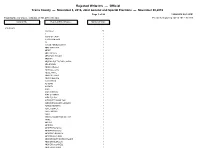

Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 1 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT <no name> 58 A 2 A BAG OF CRAP 1 A GIANT METEOR 1 AA 1 AARON ABRIEL MORRIS 1 ABBY MANICCIA 1 ABDEF 1 ABE LINCOLN 3 ABRAHAM LINCOLN 3 ABSTAIN 3 ABSTAIN DUE TO BAD CANDIA 1 ADA BROWN 1 ADAM CAROLLA 2 ADAM LEE CATE 1 ADELE WHITE 1 ADOLPH HITLER 2 ADRIAN BELTRE 1 AJANI WHITE 1 AL GORE 1 AL SMITH 1 ALAN 1 ALAN CARSON 1 ALEX OLIVARES 1 ALEX PULIDO 1 ALEXANDER HAMILTON 1 ALEXANDRA BLAKE GILMOUR 1 ALFRED NEWMAN 1 ALICE COOPER 1 ALICE IWINSKI 1 ALIEN 1 AMERICA DESERVES BETTER 1 AMINE 1 AMY IVY 1 ANDREW 1 ANDREW BASAIGO 1 ANDREW BASIAGO 1 ANDREW D BASIAGO 1 ANDREW JACKSON 1 ANDREW MARTIN ERIK BROOKS 1 ANDREW MCMULLIN 1 ANDREW OCONNELL 1 ANDREW W HAMPF 1 Rejected Write-Ins — Official Travis County — November 8, 2016, Joint General and Special Elections — November 08,2016 Page 2 of 28 12/08/2016 02:12 PM Total Number of Voters : 496,044 of 761,470 = 65.14% Precincts Reporting 247 of 268 = 92.16% Contest Title Rejected Write-In Names Number of Votes PRESIDENT Continued.. ANN WU 1 ANNA 1 ANNEMARIE 1 ANONOMOUS 1 ANONYMAS 1 ANONYMOS 1 ANONYMOUS 1 ANTHONY AMATO 1 ANTONIO FIERROS 1 ANYONE ELSE 7 ARI SHAFFIR 1 ARNOLD WEISS 1 ASHLEY MCNEILL 2 ASIKILIZAYE 1 AUSTIN PETERSEN 1 AUSTIN PETERSON 1 AZIZI WESTMILLER 1 B SANDERS 2 BABA BOOEY 1 BARACK OBAMA 5 BARAK -

Himpanzee C Chronicle

An Exclusive Publication Produced By Chimp Haven, Inc. VOLUME IX ISSUE 2 SUMMER 2009 HIMPANZEE www.chimphaven.org C CHRONICLE INSIDE THIS ISSUE: PET CHIMPANZEES HAVE BEEN IN THE NEWS THIS YEAR. Travis, who attacked a woman in Connecticut, was shot to death. Timmie was shot in Missouri when he escaped and attacked a deputy. There are countless more pet chimpanzees living in private homes throughout the United States. This edition of the Chimpanzee Chronicle discusses this serious issue. Please share it with others. WHY CHIMPANZEES DON’T MAKE GOOD PETS By Linda Brent, PhD, President and Director When chimpanzees become pets, the outcome for them or their human “family” is rarely a good one. Chimpanzees are large, wild animals who are highly intelligent and require a great deal of socialization with their mother and other chimpanzees. Sanctuaries most often hear about pet chimpanzees when they reach adolescence and are too difficult to manage any longer. Often, they bite someone or break household items. Sometimes they get loose or seriously attack a person. Generally speaking, these actions are part of normal chimpanzee behavior. An adolescent male chimpanzee begins to try to dominate others as he works his way up the dominance hierarchy or social ladder. He does this by BOARD OF displaying, hitting and throwing objects, and sometimes attacking others. Pet chimpanzees do not have the benefit of a normal social group as an outlet for their behavior, and often these DIRECTORS behaviors are directed at human caregivers or strangers. Since chimpanzees can easily weigh as much as a person—but are far stronger—they are obviously dangerous animals to have in the Thomas Butler, D.V.M., M.S. -

Proposal for Inclusion of the Chimpanzee

CMS Distribution: General CONVENTION ON MIGRATORY UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 25 May 2017 SPECIES Original: English 12th MEETING OF THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES Manila, Philippines, 23 - 28 October 2017 Agenda Item 25.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF THE CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDIX I AND II OF THE CONVENTION Summary: The Governments of Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania have jointly submitted the attached proposal* for the inclusion of the Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) on Appendix I and II of CMS. *The geographical designations employed in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the CMS Secretariat (or the United Nations Environment Programme) concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The responsibility for the contents of the document rests exclusively with its author. UNEP/CMS/COP12/Doc.25.1.1 PROPOSAL FOR THE INCLUSION OF CHIMPANZEE (Pan troglodytes) ON APPENDICES I AND II OF THE CONVENTION ON THE CONSERVATION OF MIGRATORY SPECIES OF WILD ANIMALS A: PROPOSAL Inclusion of Pan troglodytes in Appendix I and II of the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals. B: PROPONENTS: Congo and the United Republic of Tanzania C: SUPPORTING STATEMENT 1. Taxonomy 1.1 Class: Mammalia 1.2 Order: Primates 1.3 Family: Hominidae 1.4 Genus, species or subspecies, including author and year: Pan troglodytes (Blumenbach 1775) (Wilson & Reeder 2005) [Note: Pan troglodytes is understood in the sense of Wilson and Reeder (2005), the current reference for terrestrial mammals used by CMS). -

Supreme Court of the State of New York County of New York ______

SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF NEW YORK COUNTY OF NEW YORK __________________________________________________ In the Matter of a Proceeding under Article 70 of the CPLR for a Writ of Habeas Corpus, THE NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., on behalf of KIKO, MEMORANDUM OF Petitioner, LAW IN SUPPORT OF -against- PETITION FOR HABEAS CORPUS CARMEN PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., CHRISTIE E. Index No. PRESTI, individually and as an officer and director of The Primate Sanctuary, Inc., and THE PRIMATE SANCTUARY, INC., Respondents. __________________________________________________ Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5 Dunhill Road New Hyde Park, NY 11040 Phone (516) 747-4726 Steven M. Wise, Esq. Attorney for Petitioner 5195 NW 112th Terrace Coral Springs, FL 33076 Phone (954) 648-9864 Elizabeth Stein, Esq. Steven M. Wise, Esq. Subject to pro hac vice admission January_____, 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ................................................................................................ v I. SUMMARY OF NEW GROUNDS AND FACTS NEITHER PRESENTED NOR DETERMINED IN NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC., EX REL. KIKO v. PRESTI OR NONHUMAN RIGHTS PROJECT, INC. ON BEHALF OF TOMMY v. LAVERY. ............................................................................................................. 1 II. INTRODUCTION AND PROCEDURAL HISTORY .................................................... 6 III. STATEMENT OF FACTS ........................................................................................... -

The Bonobo and Me

THE BONOBO AND ME - COMPARING FAMILY TREES A PICTORIAL PRESENTATION With Marian Brickner A Campus Outreach Program in Science Education In cooperation with The University of Missouri-St. Louis Grade Level: Pre K-6 Pre-Visit Activities: Discuss what a family tree is and help students construct one of their family if possible. Presentation Time Period: Varies from 30-60 minutes as wanted. Materials: 1. A black “portfolio” case with several pictures 13 x 19, several 8 x 10's 2. A round “circular portfolio” case with a 5-foot U.S. map with ribbons on it showing where zoos are located that have Bonobo families. 3. Life size portrait of an adult Bonobo. 4. A weighted chain the average length of an adult male Bonobo (119cm) and one for the average adult female (111cm). 5. Large globe. 6. Skeletal hands, feet and skull replicas of humans (Homo sapiens), chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes), and Bonobo (Pan paniscus). 7. One weight of 2 1/2 pounds and one 7 pounds. Introduction to Presentation: “Hi, I am Marian Brickner, a photographer. I am working on a book about a Bonobo family tree. Today I will introduce you to a family you may never have met yet.” Has anyone heard of a Bonobo? What do you think a Bonobo might be? What can you tell me about them? “Bonobos are one of the Great Apes.” Who can tell me an example of a great ape? “Scientists call them by their scientific name Pan paniscus.” What is the scientific name of human beings? Historical Perspective: “I have been following the family of a Bonobo named Linda.” (Show picture of Linda.) “Linda lives in Milwaukee and was born in 1956 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, (Zaire) Africa in the central Congo Basin.” If she was born in 1956, how old is Linda today? Can anyone show me on the globe where she came from? Where do we live? “Linda has seven children, five girls and two boys.