The Uses and Limitations of Science Advisors 39 CHAPTER 3 Relationships with Other Powerful Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jerome Wiesner Was a Creative Force at MIT for the Last Half Century

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES JEROME BERT WIESNER 1915–1994 A Biographical Memoir by LOUIS D. SMULLIN Biographical Memoirs, VOLUME 78 PUBLISHED 2000 BY THE NATIONAL ACADEMY PRESS WASHINGTON, D.C. Copyright by Karsh, Ottawa JEROME BERT WIESNER May 30, 1915–October 21, 1994 BY LOUIS D. SMULLIN EROME WIESNER—JERRY to almost everybody—led an excit- J ing and productive life and, more than most, he made a difference. His career, the offices he held and the honors he received are spelled out in the MIT obituary notice at the time of his death. As interesting and impressive as is the list of offices and honors, even more interesting is his transformation from a young engineer just out of college to an “electronic warrior” during World War II, to a “cold warrior” during the early days of the “missile gap,” and finally to a leading spokesman for the nuclear test ban and a worker for nuclear disarmament. Jerry and his younger sister, Edna, were the children of Joseph and Ida Wiesner, each of whom had come to the United States at about the turn of the century. To escape having to take violin lessons, at age nineteen, Joseph had run away from his parents in Vienna in about 1892 and had shipped out to places as far away as Alaska and the California gold fields before landing in New York. (Edna remembers her father telling stories about meeting and drinking with Jack London in Alaska.) Ida had come from Romania to New York with her younger sister. She worked in the gar- ment industry and then as a housekeeper until she and 3 4 BIOGRAPHICAL MEMOIRS Joseph met and married in 1914. -

Feature Multiple Means to an End: a Reexamination of President Kennedy’S Decision to Go to the Moon by Stephen J

Feature Multiple Means to an End: A Reexamination of President Kennedy’s Decision to Go to the Moon By Stephen J. Garber On May 25, 1961, in his famously special “Urgent National Needs” speech to a joint session of Congress, President John E Kennedy made a dramatic call to send Americans to the Moon “before this decade is out.”’ After this resulted in the highly successful and publicized ApoZZo Program that indeed safely flew humans to the Moon from 1969-1972, historians and space aficio- nados have looked back at Kennedy’s decision in varying ways. Since 1970,2 most social scientists have believed that Kennedy made a single, rational, pragmatic choice to com- CHAT WITH THE AUTHOR pete with the Soviet Union in the arena of space exploration Please join us in a “chat session” with the au- as a way to achieve world prestige during the height of the thor of this article, Stephen J. Garber. In this “chat session,” you may ask Mr. Garber or the Quest Cold War. As such, the drama of space exploration served staff questions about this article, or other ques- simply as a means to an end, not as an goal for its own sake. tions about research and writing the history of Contrary to this approach, some space enthusiasts have spaceflight. The “chat” will be held on Thursday, argued in hindsight that Kennedy pushed the U.S. to explore December 9,7:00CDT. We particularly welcome boldly into space because he was a visionary who saw space Quest subscribers, but anyone may participate. -

Project Apollo: Americans to the Moon John M

Chapter Two Project Apollo: Americans to the Moon John M. Logsdon Project Apollo, the remarkable U.S. space effort that sent 12 astronauts to the surface of Earth’s Moon between July 1969 and December 1972, has been extensively chronicled and analyzed.1 This essay will not attempt to add to this extensive body of literature. Its ambition is much more modest: to provide a coherent narrative within which to place the various documents included in this compendium. In this narrative, key decisions along the path to the Moon will be given particular attention. 1. Roger Launius, in his essay “Interpreting the Moon Landings: Project Apollo and the Historians,” History and Technology, Vol. 22, No. 3 (September 2006): 225–55, has provided a com prehensive and thoughtful overview of many of the books written about Apollo. The bibliography accompanying this essay includes almost every book-length study of Apollo and also lists a number of articles and essays interpreting the feat. Among the books Launius singles out for particular attention are: John M. Logsdon, The Decision to Go to the Moon: Project Apollo and the National Interest (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1970); Walter A. McDougall, . the Heavens and the Earth: A Political History of the Space Age (New York: Basic Books, 1985); Vernon Van Dyke, Pride and Power: the Rationale of the Space Program (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1964); W. Henry Lambright, Powering Apollo: James E. Webb of NASA (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1995); Roger E. Bilstein, Stages to Saturn: A Technological History of the Apollo/Saturn Launch Vehicles, NASA SP-4206 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1980); Edgar M. -

Download Chapter 169KB

Memorial Tributes: Volume 8 JEROME BERT WIESNER 290 Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 8 JEROME BERT WIESNER 291 Jerome Bert Wiesner 1915-1994 By Paul E. Gray In or out of public positions, he never stopped caring or working for the country's good. He never thought it was not his problem . [He] performed the office of public citizen better than any contemporary I know. Anthony Lewis The New York Times October 28, 1994 Jerome B. Wiesner—engineer, educator, adviser to presidents and the young, passionate advocate for peace, and public citizen—died on October 21, 1994, at his home in Watertown, Massachusetts, at the age of seventy-nine. Throughout his life, he applied his intellect and wisdom and energy to improve the many institutions with which he was involved, to ameliorate the problems clouding the future of humankind, and to make the world a better, safer, more humane home to all its citizens. Jerry was born in Detroit, Michigan, on May 30, 1915—the son of a shopkeeper—and grew up in nearby Dearborn, where he attended the public schools. He attended the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor, where he earned bachelor of science degrees in electrical engineering and mathematics in 1937, the master of science degree in electrical engineering in 1938, and the doctor of philosophy degree in electrical engineering in 1950. Copyright National Academy of Sciences. All rights reserved. Memorial Tributes: Volume 8 JEROME BERT WIESNER 292 He began his professional career in 1937 as associate director of the University of Michigan broadcasting service, and in 1940 moved to the Acoustical Record Library of the Library of Congress, where he served as chief engineer. -

Neri Oxman Material Ecology

ANTONELLI THE NERI OXMAN CALLS HER DESIGN APPROACH MATERIAL ECOLOGY— A PROCESS THAT DRAWS ON THE STRUCTURAL, SYSTEMIC, AND AESTHETIC WISDOM OF NATURE, DISTILLED AND DEPLOYED THROUGH COMPUTATION AND DIGITAL FABRICATION. THROUGHOUT HER TWENTY- ECOLOGY MATERIAL NERI OXMAN NERI OXMAN YEAR CAREER, SHE HAS BEEN A PIONEER OF NEW MATERIALS AND CONSTRUCTION PROCESSES, AND A CATALYST FOR DYNAMIC INTERDISCIPLINARY COLLABORATIONS. WITH THE MEDIATED MATTER MATERIAL GROUP, HER RESEARCH TEAM AT THE MIT MEDIA LAB, OXMAN HAS PURSUED RIGOROUS AND DARING EXPERIMENTATION THAT IS GROUNDED IN SCIENCE, PROPELLED BY VISIONARY THINKING, AND DISTINGUISHED BY FORMAL ELEGANCE. ECOLOGY PUBLISHED TO ACCOMPANY A MONOGRAPHIC EXHIBITION OF OXMAN’S WORK AT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK, NERI OXMAN: MATERIAL ECOLOGY FEATURES ESSAYS BY PAOLA ANTONELLI AND CATALOGUE HADAS A. STEINER. ITS DESIGN, BY IRMA BOOM, PAYS HOMAGE TO STEWART BRAND’S LEGENDARY WHOLE EARTH CATALOG, WHICH CELEBRATED AND PROVIDED RESOURCES FOR A NEW ERA OF AWARENESS IN THE LATE 1960S. THIS VOLUME, IN TURN, HERALDS A NEW ERA OF ECOLOGICAL AWARENESS—ONE IN WHICH THE GENIUS OF NATURE CAN BE HARNESSED, AS OXMAN IS DOING, TO CREATE TOOLS FOR A BETTER FUTURE. Moma Neri Oxman Cover.indd 1-3 9.01.2020 14:24 THE NERI OXMAN MATERIAL ECOLOGY CATALOGUE PAOLA ANTONELLI WITH ANNA BURCKHARDT THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART, NEW YORK × Silk Pavilion I Imaginary Beings: Doppelgänger Published in conjunction with the exhibition Published by Neri Oxman: Material Ecology, at The Museum of The Museum of Modern Art, New York Modern Art, New York, February 22–May 25, 2020. 11 West 53 Street CONTENTS Organized by Paola Antonelli, Senior Curator, New York, New York 10019 Department of Architecture and Design, www.moma.org and Director, Research and Development; and Anna Burckhardt, Curatorial Assistant, © 2020 The Museum of Modern Art, New York 9 FOREWORD Department of Architecture and Design Certain illustrations are covered by claims to copyright cited on page 177. -

Seeds of Discovery: Chapters in the Economic History of Innovation Within NASA

Seeds of Discovery: Chapters in the Economic History of Innovation within NASA Edited by Roger D. Launius and Howard E. McCurdy 2015 MASTER FILE AS OF Friday, January 15, 2016 Draft Rev. 20151122sj Seeds of Discovery (Launius & McCurdy eds.) – ToC Link p. 1 of 306 Table of Contents Seeds of Discovery: Chapters in the Economic History of Innovation within NASA .............................. 1 Introduction: Partnerships for Innovation ................................................................................................ 7 A Characterization of Innovation ........................................................................................................... 7 The Innovation Process .......................................................................................................................... 9 The Conventional Model ....................................................................................................................... 10 Exploration without Innovation ........................................................................................................... 12 NASA Attempts to Innovate .................................................................................................................. 16 Pockets of Innovation............................................................................................................................ 20 Things to Come ...................................................................................................................................... 23 -

Invoking the Experts: Theantiballistic Missile Debate

58 Advising or Legitimizing1 dated April 3, 1970: "lt would be unfortunate to leave the impremon that the [Garwin CHAPTER 5 teport) was 'highly crltical' of the SST program.'' [ Reprinted in Congressional Record 111 (1971): 32125.) DuBridge's letter stated further that the Garwin Report was prepared at President Nixon's request and would not be released; the quoted Statement was evidently intended to deceive Reuss as to the report's actual conclusions. 1. NBC radio interview with Rep. Reuss, reprinted in Congre11ional Record 115 (1969): 34743. Invoking the Experts : 8. Congreuional Record 115 (1969): 32599-32613. 9. lbid., p. 32606. 10. lbid., p. 32608. 11. Ibid., p. 3 261 o. The Antiballistic Missile 12. lbid., p. 32607. 13. U.S. Congress. House. Committee on Appropriations, Department of Transportation and Related Agencie1 Approprilltions for 1971, Part 3, April 23, 1970, pp. 980-994. Debate 14. Quoted in Saturday Review, August 15, 1970. lS. The suit was füed by the American Civil Ll"berties Union on behalf of Gary A. Soucie, executive director of the Friends of the Earth, and W. lloyd Tupling, Washington representative of the Siena Club. Peter L Koff of Boston was the volunteer attomey. 16. Letter from Edward E. David, Jr., PJesldent Nixon's science advisor, to Peter L Koff, August 17, 1971. 17. Subcommittee on Physical Effects, NAS-NRC Committee on SST-Sonic Boom, Report on Physical Effectl of the Sonlc Boom (Washington, D.C.: National Academy of Sciences. February 1968). 18. New Y«k Time1, March S, 1968. (This story was run in early editions but removed De. -

Celebrating 40 Years of Rita Allen Foundation Scholars 1 PEOPLE Rita Allen Foundation Scholars: 1976–2016

TABLE OF CONTENTS ORIGINS From the President . 4 Exploration and Discovery: 40 Years of the Rita Allen Foundation Scholars Program . .5 Unexpected Connections: A Conversation with Arnold Levine . .6 SCIENTIFIC ADVISORY COMMITTEE Pioneering Pain Researcher Invests in Next Generation of Scholars: A Conversation with Kathleen Foley (1978) . .10 Douglas Fearon: Attacking Disease with Insights . .12 Jeffrey Macklis (1991): Making and Mending the Brain’s Machinery . .15 Gregory Hannon (2000): Tools for Tough Questions . .18 Joan Steitz, Carl Nathan (1984) and Charles Gilbert (1986) . 21 KEYNOTE SPEAKERS Robert Weinberg (1976): The Genesis of Cancer Genetics . .26 Thomas Jessell (1984): Linking Molecules to Perception and Motion . 29 Titia de Lange (1995): The Complex Puzzle of Chromosome Ends . .32 Andrew Fire (1989): The Resonance of Gene Silencing . 35 Yigong Shi (1999): Illuminating the Cell’s Critical Systems . .37 SCHOLAR PROFILES Tom Maniatis (1978): Mastering Methods and Exploring Molecular Mechanisms . 40 Bruce Stillman (1983): The Foundations of DNA Replication . .43 Luis Villarreal (1983): A Life in Viruses . .46 Gilbert Chu (1988): DNA Dreamer . .49 Jon Levine (1988): A Passion for Deciphering Pain . 52 Susan Dymecki (1999): Serotonin Circuit Master . 55 Hao Wu (2002): The Cellular Dimensions of Immunity . .58 Ajay Chawla (2003): Beyond Immunity . 61 Christopher Lima (2003): Structure Meets Function . 64 Laura Johnston (2004): How Life Shapes Up . .67 Senthil Muthuswamy (2004): Tackling Cancer in Three Dimensions . .70 David Sabatini (2004): Fueling Cell Growth . .73 David Tuveson (2004): Decoding a Cryptic Cancer . 76 Hilary Coller (2005): When Cells Sleep . .79 Diana Bautista (2010): An Itch for Knowledge . .82 David Prober (2010): Sleeping Like the Fishes . -

Strengthening the Role of Universities in National Science Policymaking

A JEROME B. WIESNER SYMPOSIUM Strengthening the Role of Universities in National Science Policymaking March 30–31, 2015 Symposium Summary FEBRUARY 2016 SPONSORED BY The University of Michigan Office of Research Organizing Committee Homer A. Neal (chair) Deborah Ball Rosina Bierbaum Lennard A. Fisk S. Jack Hu Vasudevan Lakshminarayanan Gilbert Omenn Jason Owen-Smith Carl Simon James Wells Lois Vasquez More information is available at: Wiesnersymposium.umich.edu Table of Contents Executive Summary 1 Introduction 3 Recommendations 5 Conclusion 16 Appendix A—Symposium Agenda 18 Appendix B—Speakers and Panelists 21 Appendix C—Biography of Jerome B. Wiesner 26 Executive Summary On March 30 – 31, 2015, a symposium on “Strengthening the Role of Universities in National Recommendation 12: Establish state-level Science Policymaking” was held at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. Sponsored by the academies of science to foster improved U-M Office of the Vice President of Research, the meeting was convened to explore how interactions between faculty and the public universities can more productively inform and engage in the formulation of national policies at the local level. affecting the sciences and engineering as well as policies involving the effective application Recommendation 13: Conduct rigorous of science and technology to a host of societal challenges. An explicit goal was to develop studies of academia from a systemic and recommend specific action items encompassing education, research, and engagement to viewpoint to show qualitatively and present to the leadership at the nation’s universities. quantitatively where research funding comes An overarching theme that emerged was that campuses must cultivate a culture of public from, how it is spent, and what the returns service, encouraging both faculty and students to become “civic scientists” who engage in on investment are for individuals and society current issues related to science policy and science-based policy and draw on their special as a whole. -

And Technology Massachusetts Institute Of

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 095 293 CE 001 841 AUTHOR Ruina, Edith, Ed. TITLE Women in Science and Technology. INSTITUTION Massachusetts Inst. of Tech., Cambridge. SPONS AGENCY Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, New York, N.Y.; Carnegie Corp. of New York, N.Y.; General Electric Foundation, Ossining, N.Y. PUB DATE May 73 NOTE 43p.; A Report on the Workshop on Women in Science and Technology Massachusetts Institute of Technology, May 21-23, 1973) AVAILABLE FROM Room 10-140, Workshop on Women in Science and Technology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139 ($2.00) EDRS PRICE MF-$0.75 HC-$1.85 PLUS POSTAGE DESCRIPTORS Adult Education; *Career Planning; Counseling Programs; Employer Attitudes; Employment; Females; Labor Force; School Industry Relationship; *Science Careers; Secondary Schools; *Technology; *Womens Education; *Working Women; Workshops ABSTRACT The ultimate aim of the Workshop on Women in Science and Technology was to stimulate parents and daughters to explore technical and scientific careers. Approximately 100 men and women from diverse organizations (industry, governmental agencies, non-profit institutions, Federal and State agencies, public schools, special vocational schools, advisory committees, women's organizations, and universities) attended the forum. The focus of the program was primarily on secondary schools and eluployinginstitutions in that they seemed most directly related to women's occupational decisions and opportunities. The employer's contribution to the supply of women in technical and scientific occupations was perceived as the attraction and retention of women employees andcommunication and interaction with educational and other institutions. Participants emphasized that the secondary schools' objectives are not and should not be limited to occupational preparation; students need to become aware of manpower projections, demographic factors,combining family/work roles, women in the labor force, and continuing education. -

Chapter 14 “We Choose to Go to the Moon” JFK and the Race for The

Chapter 14 “We Choose to Go to the Moon” JFK and the Race for the Moon, 1960-1963 Richard E. Collin Space Exploration on the Eve of the Kennedy Presidency At the time of John F. Kennedy's election to the U.S. Presidency on November 8, 1960, the Space Age was three years old. The Soviet Union had launched it with a successful orbiting in October 1957 of Sputnik I, an aluminum ball measuring 23 inches in diameter and weighing 184 pounds. It was not until the following January in 1958 that the United States orbited its first satellite, Explorer I. Meanwhile, the Soviet Union continued its high-profile thrust into space, capturing the world’s imagination with a series of “firsts” – orbiting the first living creature, a female dog named Laika (in Sputnik II, November 3, 1957); sending the first manmade probe to impact another world, in this case, the Moon (Luna II, September 12, 1959); and taking the first photographs of the far side of the Moon (Luna III, October 4, 1959). Space, JFK and the 1960 Campaign A key theme in Kennedy's race for the White House was his claim that the country's prestige had declined under the Eisenhower Administration, principally because of its record in space. During the campaign, Kennedy pounded hard about what he perceived as America's failures in space. Yet he remained silent about what he had in mind for his own program. He was not at all convinced that manned space flight should play a role in his Administration.1 As U.S. -

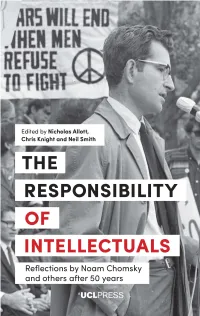

The Responsibility of Intellectuals

The Responsibility of Intellectuals EthicsTheCanada Responsibility and in the FrameAesthetics ofofCopyright, TranslationIntellectuals Collections and the Image of Canada, 1895– 1924 ExploringReflections the by Work Noam of ChomskyAtxaga, Kundera and others and Semprún after 50 years HarrietPhilip J. Hatfield Hulme Edited by Nicholas Allott, Chris Knight and Neil Smith 00-UCL_ETHICS&AESTHETICS_i-278.indd9781787353008_Canada-in-the-Frame_pi-208.indd 3 3 11-Jun-1819/10/2018 4:56:18 09:50PM First published in 2019 by UCL Press University College London Gower Street London WC1E 6BT Available to download free: www.ucl.ac.uk/ucl-press Text © Contributors, 2019 Images © Copyright holders named in captions, 2019 The authors have asserted their rights under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as authors of this work. A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from The British Library. This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-commercial Non-derivative 4.0 International license (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). This license allows you to share, copy, distribute and transmit the work for personal and non-commercial use providing author and publisher attribution is clearly stated. Attribution should include the following information: Allott, N., Knight, C. and Smith, N. (eds). The Responsibility of Intellectuals: Reflections by Noam Chomsky and others after 50 years. London: UCL Press, 2019. https://doi.org/10.14324/ 111.9781787355514 Further details about CC BY licenses are available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Any third-party material in this book is published under the book’s Creative Commons license unless indicated otherwise in the credit line to the material.