Report Truth Commission on the Responsibility of Israeli Society For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005 BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights i BADIL is a member of the Global Palestine Right of Return Coalition Preface The Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons is published annually by BADIL Resource Center. The Survey provides an overview of one of the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee and displaced populations in the world today. It is estimated that two out of every five of today’s refugees are Palestinian. The Survey has several objectives: (1) It aims to provide basic information about Palestinian displacement – i.e., the circumstances of displacement, the size and characteristics of the refugee and displaced population, as well as the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons; (2) It aims to clarify the framework governing protection and assistance for this displaced population; and (3) It sets out the basic principles for crafting durable solutions for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, consistent with international law, relevant United Nations Resolutions and best practice. In short, the Survey endeavors to address the lack of information or misinformation about Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, and to counter political arguments that suggest that the issue of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons can be resolved outside the realm of international law and practice applicable to all other refugee and displaced populations. The Survey examines the status of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons on a thematic basis. Chapter One provides a short historical background to the root causes of Palestinian mass displacement. -

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

A House in the Almanshiyya Neighborhood in the Town of Jaffa. Today: the Etzel Museum in Tel Avivyafo

A house in the alManshiyya neighborhood in the town of Jaffa. Today: The Etzel Museum in Tel AvivYafo (2008. Photo: Amaya Galili). ❖ What do you see in the picture? What message does this building’s architecture transmit? ❖ AlManshiyya was a Palestinian neighborhood in Jaffa, on the coast, built at the end of the 1870's, at the same time as Neve Tzedek, a Jewish neighborhood in southwestern Tel Aviv. Until 1948, Palestinians also lived in Neve Tzedek, and Jews lived in alManshiyya. The destruction of the neighborhood began with its capture in 1948 and continued into the 1970’s. Only two of the original buildings in alManshiyya remained: the Jaffa railroad station and the Hassan Beq Mosque. The building in the photo was turned into the Etzel Museum; Etzel was the organization that captured Jaffa in 1948. The museum building preserved only the lower part of the Palestinian structure, and a square black glass construction was added on top of it. ❖ The building is clearly visible from the shoreline, from Tel Aviv as well as from Jaffa, and looks as if its aim was to symbolize and emphasize the Israeli presence and its conquest of the structures and lives of its Palestinian inhabitants. There’s no indication, inside or outside the museum, of whose house this was, and no mention of the neighborhood in which it stood. A mosque in the village of Wadi Hunayn. Today it’s a synagogue near Nes Ziona (1987. Photo: Ra’fi Safiya). ❖ How do we know this was a mosque? ❖ We can see the architectural elements that characterized Muslim architecture in the region: the building has a dome and arched windows. -

Deir Yassin: History of a Lie

The Zionist Organization of America March 9, 1998 Deir Yassin: History of a Lie Introduction For fi fty years, critics of Israel have used the battle of Deir Yassin to blacken the image of the Jewish State, alleging that Jewish fi ghters mas- sacred hundreds of Arab civilians during a battle in that Arab village near Jerusalem in 1948. This analysis brings to light, for the fi rst time, a number of important documents that have never previously appeared in English, which help clarify what really happened in Deir Yassin on that fateful day. One is a research study conducted by a team of researchers from Bir Zeit University, an Arab university now situated in Palestinian Author- ity territory, concerning the history of Deir Yassin and the details of the battle. The researchers interviewed numerous former residents of the town and reached startling conclusions concerning the actual number of people killed in the battle. The second important work on this subject that has never previously appeared in English, and which was consulted for this study, is a his- tory of the 1948 war by Professor Uri Milstein, one of Israel’s most distinguished military historians. His 13-volume study of the 1948 war includes a section on Deir Yassin based on detailed interviews with the participants in the battle and previously-unknown archival documents. Professor Milstein’s meticulous research has been praised by academics from across the political spectrum.1 Another document used in this study is the protocols of a 1952 hear- ing, in which, for the fi rst and only time, Israeli judges heard eyewitness testimony from participants in the events at Deir Yassin and issued a ruling that has important implications for understanding what happened in that battle. -

The Politics of Home in Jerusalem: Partitions, Parks, and Planning Futures

THE POLITICS OF HOME IN JERUSALEM: PARTITIONS, PARKS, AND PLANNING FUTURES Nathan W. Swanson A dissertation submitted to the faculty at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Geography. Chapel Hill 2016 Approved by: Banu Gökarıksel Sara Smith John Pickles Sarah Shields Nadia Yaqub © 2016 Nathan W. Swanson ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Nathan W. Swanson: The Politics of Home in Jerusalem: Partitions, Parks, and Planning Futures (Under the direction of Banu Gökarıksel) At a time when Palestine and Palestinians are ubiquitously framed through the “Israeli- Palestinian conflict” and the “peace process”, the spaces of everyday life for Palestinians are often ignored. This is in spite of the fact that so many of the Israeli policies and technologies of occupation and settlement are experienced materially by Palestinians in these spaces. In this dissertation, then, drawing on feminist geopolitics, I consider everyday Palestinian spaces like the home, neighborhood, and village—with a focus on Jerusalem—to better understand geographies of occupation and settlement in Palestine/Israel today. I argue, through attention to Palestinian experiences on the ground, that widespread representations of Jerusalem as either a “united” or “divided” city fail to capture the Palestinian experience, which is actually one of fragmentation, both physical and social. As a case study in fragmentation, I turn to the zoning of Israeli national parks in and between Palestinian neighborhoods, arguing that parks have served the purposes of settlement in less politicized ways than West Bank settlement blocs, but like the settlement blocs, have resulted in dispossession and restrictions on Palestinian construction, expansion, and movement. -

Palestine Between Memory and the Anticolonial Art of Resistance

After the Last Frontiers: Palestine Between Memory and the Anticolonial Art of Resistance by Huda Salha A thesis exhibition presented to OCAD University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts In Interdisciplinary Master’s in Art, Media and Design Toronto, Ontario, Canada, 2020 I Abstract After the Last Frontiers, my thesis exhibition, aims to raise questions about forms of oppression and violence practiced by the oppressive colonial powers in Palestine and, by extension, the world. The thesis explores the possibilities of artists’ contributions to social and political change by shedding light on my motives, narratives, and art practice, and by comparing my artworks to those by artists who have tackled similar issues. The art produced for this thesis exhibition is intended to act as an anticolonial form of resistance and activism. The exhibition consists of installations of objects that represent sites of memory, reviving the collective memory of people and land. In my case, I wish to commemorate the places that were stolen, the over 750,000 displaced Palestinians and their descendants, amounting to millions, the thousands of Palestinians killed since 1948, the hundreds of thousands of acres of olive trees uprooted, and the over 500 Palestinian villages and towns obliterated. Based on relevant historical and archival artifacts, this practice-based thesis underscores the significance of documentation and archival material in memory tracing/maintaining, and its relevance to the Palestinian case, and, in turn, the Israeli hegemonic narrative in the West. II Acknowledgements I acknowledge the ancestral and traditional territories of the Indigenous nations of Canada, “who are the original owners and custodians of the land on which [I] stand and create”(OCADU), the land where I live and raise my children in peace, the land where I have sought refuge. -

Deir Yassin Massacre (1948)

Document B The 1948 War Deir Yassin Massacre Deir Yassin Massacre (1948) Early in the morning of April 9, 1948, commandos of the Irgun (headed by Menachem Begin) and the Stern Gang attacked Deir Yassin, a village with about 750 Palestinian residents. The village lay outside of the area to be assigned by the United Nations to the Jewish State; it had a peaceful reputation. But it was located on high ground in the corridor between Tel Aviv and Jerusalem. Deir Yassin was slated for occupation under Plan Dalet and the mainstream Jewish defense force, the Haganah, authorized the irregular terrorist forces of the Irgun and the Stern Gang to perform the takeover. In all over 100 men, women, and children were systematically murdered. Fifty-three orphaned children were literally dumped along the wall of the Old City, where they were found by Miss Hind Husseini and brought behind the American Colony Hotel to her home, which was to become the Dar El-Tifl El-Arabi orphanage. (source: http://www.deiryassin.org) Natan Yellin-Mor (Jewish) responded to the massacre: When I remember what led to the massacre of my mother, sister and other members of my family, I can’t accept this massacre. I know that in the heat of battle such things happen, and I know that the people who do these things don’t start out with such things in mind. They kill because their own comrades have being killed and wounded, and they want their revenge at that very moment. But who tells them to be proud of such deeds? (From Eyal naveh and Eli bar-Navi, Modern Times, part 2, page 228) One of the young men of the Deir Yassin village reported what he has been told by his mother: My mother escaped with my two small brothers, one-year old and two-years old. -

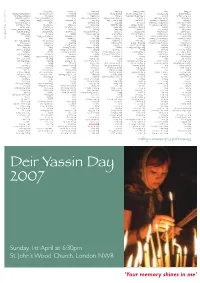

F-Dyd Programme

‘Your memory shines in me’ in shines memory ‘Your St. John’s Wood Church, London NW8 London Church, Wood John’s St. Sunday, 1st April at 6:30pm at April 1st Sunday, 2007 Deir Yassin Day Day Yassin Deir Destroyed Palestinian villages Amqa Al-Tira (Tirat Al-Marj, Abu Shusha Umm Al-Zinat Deir 'Amr Kharruba, Al-Khayma Harrawi Al-Zuq Al-Tahtani Arab Al-Samniyya Al-Tira Al-Zu'biyya) Abu Zurayq Wa'arat Al-Sarris Deir Al-Hawa Khulda, Al-Kunayyisa (Arab Al-Hamdun), Awlam ('Ulam) Al-Bassa Umm Ajra Arab Al-Fuqara' Wadi Ara Deir Rafat Al-Latrun (Al-Atrun) Hunin, Al-Husayniyya Al-Dalhamiyya Al-Birwa Umm Sabuna, Khirbat (Arab Al-Shaykh Yajur, Ajjur Deir Al-Shaykh Al-Maghar (Al-Mughar) Jahula Ghuwayr Abu Shusha Al-Damun Yubla, Zab'a Muhammad Al-Hilu) Barqusya Deir Yassin Majdal Yaba Al-Ja'una (Abu Shusha) Deir Al-Qasi Al-Zawiya, Khirbat Arab Al-Nufay'at Bayt Jibrin Ishwa', Islin (Majdal Al-Sadiq) Jubb Yusuf Hadatha Al-Ghabisyya Al-'Imara Arab Zahrat Al-Dumayri Bayt Nattif Ism Allah, Khirbat Al-Mansura (Arab Al-Suyyad) Al-Hamma (incl. Shaykh Dannun Al-Jammama Atlit Al-Dawayima Jarash, Al-Jura Al-Mukhayzin Kafr Bir'im Hittin & Shaykh Dawud) Al-Khalasa Ayn Ghazal Deir Al-Dubban Kasla Al-Muzayri'a Khirbat Karraza Kafr Sabt, Lubya Iqrit Arab Suqrir Ayn Hawd Deir Nakhkhas Al-Lawz, Khirbat Al-Na'ani Al-Khalisa Ma'dhar, Al-Majdal Iribbin, Khirbat (incl. Arab (Arab Abu Suwayrih) Balad Al-Shaykh Kudna (Kidna) Lifta, Al-Maliha Al-Nabi Rubin Khan Al-Duwayr Al-Manara Al-Aramisha) Jurdayh, Barbara, Barqa Barrat Qisarya Mughallis Nitaf (Nataf) Qatra Al-Khisas (Arab -

50 Years on and Stones in an Unfinished Wall Lisa Suhair Majaj

Journal of Pedagogy, Pluralism, and Practice Volume 2 | Issue 1 Article 7 Fall 2000 50 Years on and Stones in an Unfinished Wall Lisa Suhair Majaj Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/jppp Recommended Citation Majaj, Lisa Suhair (2000) "50 Years on and Stones in an Unfinished Wall," Journal of Pedagogy, Pluralism, and Practice: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.lesley.edu/jppp/vol2/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@Lesley. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Pedagogy, Pluralism, and Practice by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@Lesley. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Majaj: 50 Years on and Stones in an Unfinished Wall 51 Fifty Years On / Stones in an Unfinished Wall For Palestine Lisa Suhair Majaj 1. Fifty years on I am trying to tell the story of what was lost before my birth the story of what was there before the stone house fell mortar blasted loose rocks carted away for new purposes, or smashed the land declared clean, empty before the oranges bowed in grief blossoms sifting to the ground like snow quickly melting before my father clamped his teeth hard on the pit of exile slammed shut the door to his eyes before tears turned to disbelief disbelief to anguish anguish to helplessness helplessness to rage rage to despair before the cup was filled raised forcibly to our lips fifty years on I am trying to tell the story of what we are still losing 2. -

“We Are Victims of Our Past . . .”—Israel's Dark History Comes To

CULTURE “We Are Victims of Our Past .. .”—Israel’s Dark History Comes to Light in New Documentaries OLGA GERSHENSON he 34th annual Jerusalem and the facts of the occupation on the Zionist paramilitary forces — Irgun Film Festival opened on July ground. But once in a while, there is and Lehi — conquered the village. 13 with a screening and greet- a breach in this wall of denial, and When they ran into trouble, they ings in Sultan Pool, a valley in through the cracks one can glimpse called on the more mainstream Haga- Tbetween the West Jerusalem and the the pain and the trauma, the terrible nah for help. Approximately 110 villag- Old City. Sitting in the large amphi- toll the violence takes not only on vic- ers were killed, others were expelled. theater under the open sky, one could tims but also on perpetrators. Rumors of a massacre in Deir Yassin see the gorgeous old Jewish neighbor- The wall of denial surrounding the spread across Palestine, causing panic hood of Yemin Moshe on one side, and past is especially thick. If 1967 is dis- and leading to mass exodus of the the walls and steeples of the Old City cussed occasionally and reluctantly Arab population. The events in Deir on the other. The next day, three men, (think about such films as The Law in Yassin had far- reaching consequences Palestinian citizens of Israel, came These Parts or Censored Voices), the for both Jews and Palestinians. Argu- out of Al Aqsa Mosque and shot two 1948 is still a non- starter.