The Politics of Home in Jerusalem: Partitions, Parks, and Planning Futures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’S First Decades

Planning and Injustice in Tel-Aviv/Jaffa Urban Segregation in Tel-Aviv’s First Decades Rotem Erez June 7th, 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Stefan Kipfer A Major Paper submitted to the Faculty of Environmental Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master in Environmental Studies, York University, Toronto, Ontario, Canada Student Signature: _____________________ Supervisor Signature:_____________________ Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Abstract .............................................................................................................................................4 Foreword ...........................................................................................................................................6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................9 Chapter 1: A Comparative Study of the Early Years of Colonial Casablanca and Tel-Aviv ..................... 19 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 19 Historical Background ............................................................................................................................ -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

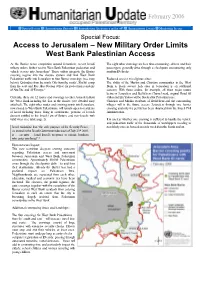

Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access

February 2006 Special Focus Humanitarian Reports Humanitarian Assistance in the oPt Humanitarian Events Monitoring Issues Special Focus: Access to Jerusalem – New Military Order Limits West Bank Palestinian Access As the Barrier nears completion around Jerusalem, recent Israeli The eight other crossings are less time-consuming - drivers and their military orders further restrict West Bank Palestinian pedestrian and passengers generally drive through a checkpoint encountering only vehicle access into Jerusalem.1 These orders integrate the Barrier random ID checks. crossing regime into the closure system and limit West Bank Palestinian traffic into Jerusalem to four Barrier crossings (see map Reduced access to religious sites: below): Qalandiya from the north, Gilo from the south2, Shu’fat camp The ability of the Muslim and Christian communities in the West from the east and Ras Abu Sbeitan (Olive) for pedestrian residents Bank to freely access holy sites in Jerusalem is an additional of Abu Dis, and Al ‘Eizariya.3 concern. With these orders, for example, all three major routes between Jerusalem and Bethlehem (Tunnel road, original Road 60 Currently, there are 12 routes and crossings to enter Jerusalem from (Gilo) and Ein Yalow) will be blocked for Palestinian use. the West Bank including the four in the Barrier (see detailed map Christian and Muslim residents of Bethlehem and the surrounding attached). The eight other routes and crossing points into Jerusalem, villages will in the future access Jerusalem through one barrier now closed to West Bank Palestinians, will remain open to residents crossing and only if a permit has been obtained from the Israeli Civil of Israel including those living in settlements, persons of Jewish Administration. -

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

Hastings (Fall 2010) Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association

UC Hastings Scholarship Repository Hastings Alumni Publications 9-1-2010 Hastings (Fall 2010) Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association Follow this and additional works at: http://repository.uchastings.edu/alumni_mag Recommended Citation Hastings College of the Law Alumni Association, "Hastings (Fall 2010)" (2010). Hastings Alumni Publications. 129. http://repository.uchastings.edu/alumni_mag/129 This is brought to you for free and open access by UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Alumni Publications by an authorized administrator of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. CONTENTS Briefings 02 FROM THE DEAN 03 FOR THE RECORD Victoria Smith '10 recently hit the jackpot on Wheel of Fortune-just in time to start repaying those student loans. 04 I SIDEBARS News and notes from the Hastings community, including a top honor for Professor Karen Musalo; an update on the Lawrence M. Nagin '65 Faculty Enrichment Fund; Professor Joan C. Williams's new study on work-family conflict; and more. In Depth 10 I TRIBUTE In honor of California Supreme Court Justice Marvin Baxter '66 and his wife, Jane Baxter, the couple's family has made a major gift to fund Hastings' new Appellate Law Center. 12 I LEADERSHIP New Chancellor & Dean Frank H. Wu shares his vision for transforming UC Hastings. 34 I STUDENT ORGANIZATIONS Students acquire valuable trial experience in Hastings' renowned Criminal Practice Clinic. 56 I CLOSING STATEMENT Maureen Corcoran '79 shares her thoughts on the evolving field of health law. Movers & Shakers ALUMNI IN ACTION They have defended accused Hollywood murderers and corporate embezzlers; they have prosecuted scammers, racketeers and price fixers . -

Integrate and Reactivate the 1968 Fair Housing Mandate Courtney L

Georgia State University College of Law Reading Room Faculty Publications By Year Faculty Publications 1-1-2016 Integrate and Reactivate the 1968 Fair Housing Mandate Courtney L. Anderson Georgia State University College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/faculty_pub Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, and the Housing Law Commons Recommended Citation Courtney L. Anderson, Integrate and Reactivate the 1968 Fair Housing Mandate, 13 Hastings Race & Poverty L.J. 1 (2016) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications By Year by an authorized administrator of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HASTINGS RACE AND POVERTY LAW JOURNAL VOLUME XIII NO. 1 WINTER 2016 ARTICLES INTEGRATE AND REACTIVATE THE 1968 FAIR HOUSING MANDATE Courtney L. Anderson LA GRAN LUCHA: LATINA AND LATINO LAWYERS, BREAKING THE LAW ON PRINCIPLE, AND CONFRONTING THE RISKS OF REPRESENTATION Marc‐Tizoc González THE OBERGEFELL MARRIAGE EQUALITY DECISION, WITH ITS EMPHASIS ON HUMAN DIGNITY, AND A FUNDAMENTAL RIGHT TO FOOD SECURITY Maxine D. Goodman NOTE POLICE TERROR AND OFFICER INDEMNIFICATION Allyssa Villanueva University of California Hastings College of the Law 200 McAllister Street, San Francisco, CA 94102 HASTINGS RACE AND POVERTY LAW JOURNAL Winter 2016 Volume 13, Issue 1 Mission Statement The Hastings Race and Poverty Law Journal is committed to promoting and inspiring discourse in the legal community regarding issues of race, poverty, social justice, and the law. This Journal is committed to addressing disparities in the legal system. -

Nationalism, Deprivation and Regionalism Among Arabs in Israel Author(S): Oren Yiftachel Source: Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol

The Political Geography of Ethnic Protest: Nationalism, Deprivation and Regionalism among Arabs in Israel Author(s): Oren Yiftachel Source: Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, New Series, Vol. 22, No. 1 (1997), pp. 91-110 Published by: Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/623053 Accessed: 19/04/2010 02:59 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=black. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Blackwell Publishing and The Royal Geographical Society (with the Institute of British Geographers) are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers. -

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: the Israeli Supreme Court

Jerusalem Chronology 2015 January Jan. 1: The Israeli Supreme Court rejects an appeal to prevent the demolition of the homes of four Palestinians from East Jerusalem who attacked Israelis in West Jerusalem in recent months. - Marabouts at Al-Aqsa Mosque confront a group of settlers touring Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 3: Palestinian MK Ahmad Tibi joins hundreds of Palestinians marching toward the Al-Aqsa Mosque in the Old City of Jerusalem to mark the Prophet Muhammad's birthday. Jan. 5: Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound while Israeli forces confiscate the IDs of Muslims trying to enter. - Around 50 Israeli forces along with 18 settlers tour Al-Aqsa compound. Jan. 8: A Jewish Israeli man is stabbed and injured by an unknown assailant while walking near the Old City’s Damascus Gate. Jan. 9: Israeli police detain at least seven Palestinians in a series of raids in the Old City over the stabbing a day earlier. - Yedioth Ahronoth reports that the Israeli Intelligence (Shabak) frustrated an operation that was intended to blow the Dome of the Rock by an American immigrant. Jan. 11: Israeli police forces detain seven Palestinians from Silwan after a settler vehicle was torched in the area. Jan. 12: A Jerusalem magistrate court has ruled that Israeli settlers who occupied Palestinian homes in East Jerusalem may not make substantial changes to the properties. - Settlers tour Al-Aqsa Mosque compound. Jan. 13: Israeli forces detained three 14-year old youth during a raid on Issawiyya and two women while leaving Al-Aqsa Mosque. Jan. 14: Jewish extremists morning punctured the tires of 11 vehicles in Beit Safafa. -

Science in Archaeology: a Review Author(S): Patrick E

Science in Archaeology: A Review Author(s): Patrick E. McGovern, Thomas L. Sever, J. Wilson Myers, Eleanor Emlen Myers, Bruce Bevan, Naomi F. Miller, S. Bottema, Hitomi Hongo, Richard H. Meadow, Peter Ian Kuniholm, S. G. E. Bowman, M. N. Leese, R. E. M. Hedges, Frederick R. Matson, Ian C. Freestone, Sarah J. Vaughan, Julian Henderson, Pamela B. Vandiver, Charles S. Tumosa, Curt W. Beck, Patricia Smith, A. M. Child, A. M. Pollard, Ingolf Thuesen, Catherine Sease Source: American Journal of Archaeology, Vol. 99, No. 1 (Jan., 1995), pp. 79-142 Published by: Archaeological Institute of America Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/506880 Accessed: 16/07/2009 14:57 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=aia. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that promotes the discovery and use of these resources. -

The Palestinian Economy in East Jerusalem, Some Pertinent Aspects of Social Conditions Are Reviewed Below

UNITED N A TIONS CONFERENC E ON T RADE A ND D EVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT Enduring annexation, isolation and disintegration New York and Geneva, 2013 Notes The designations employed and the presentation of the material do not imply the expression of any opinion on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of authorities or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. ______________________________________________________________________________ Symbols of United Nations documents are composed of capital letters combined with figures. Mention of such a symbol indicates a reference to a United Nations document. ______________________________________________________________________________ Material in this publication may be freely quoted or reprinted, but acknowledgement is requested, together with a copy of the publication containing the quotation or reprint to be sent to the UNCTAD secretariat: Palais des Nations, CH-1211 Geneva 10, Switzerland. ______________________________________________________________________________ The preparation of this report by the UNCTAD secretariat was led by Mr. Raja Khalidi (Division on Globalization and Development Strategies), with research contributions by the Assistance to the Palestinian People Unit and consultant Mr. Ibrahim Shikaki (Al-Quds University, Jerusalem), and statistical advice by Mr. Mustafa Khawaja (Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, Ramallah). ______________________________________________________________________________ Cover photo: Copyright 2007, Gugganij. Creative Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org (accessed 11 March 2013). (Photo taken from the roof terrace of the Austrian Hospice of the Holy Family on Al-Wad Street in the Old City of Jerusalem, looking towards the south. In the foreground is the silver dome of the Armenian Catholic church “Our Lady of the Spasm”. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

The Arab Bedouin Indigenous People of the Negev/Nagab

The Arab Bedouin indigenous people of the Negev/Nagab – A Short Background In 1948, on the eve of the establishment of the State of Israel, about 65,000 to 100,000 Arab Bedouin lived in the Negev/Naqab region, currently the southern part of Israel. Following the 1948 war, the state began an ongoing process of eviction of the Arab Bedouin from their dwellings. At the end of the '48 war, only 11,000 Arab Bedouin people remained in the Negev/Naqab, most of the community fled or was expelled to Jordan and Egypt, the Gaza Strip and the Sinai Peninsula. During the early 1950s and until 1966, the State of Israel concentrated the Arab Bedouin people in a under military administration. In this (سياج) ’closed zone known by the name ‘al-Siyāj period, entire villages were displaced from their locations in the western and northern Negev/Naqab and were transferred to the Siyāj area. Under the Planning and Construction Law, legislated in 1965, most of the lands in the Siyāj area were zoned as agricultural land whereby ensuring that any construction of housing would be deemed illegal, including all those houses already built which were subsequently labeled “illegal”. Thus, with a single sweeping political decision, the State of Israel transformed almost the entire Arab Bedouin collective into a population of whereas the Arab Bedouins’ only crime was exercising their basic ,״lawbreakers״ human right for adequate housing. In addition, the state of Israel denies any Arab Bedouin ownership over lands in the Negev/Naqab. It does not recognize the indigenous Arab Bedouin law or any other proof of Bedouin ownership over lands.