Passing on the Promise Holding Onto The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

PNF, No. 15, 6 April – 12 April 2016

Palestine News Forum 6/4-12/4/16 1. Gaza power plant closed due to fuel shortage (12.4.2016) Source: Al-Arabiyah The only power station in Gaza Strip has been forced to shut down due to fuel shortage as the Palestinian territory is suffering from nine years of siege by Tel Aviv. Ahmed Abu Al-Amreen, an official in Gaza Energy Ministry, said on Tuesday that the power plant has been closed since Saturday night when it ran out of fuel. Meanwhile, the United Nations said parts of the coastal sliver have been without power for 20 hours a day, compared to 12 hours previously. According to some reports, the Ramallah-based Palestinian Authority‘s recently removed a fuel tax exemp- tion, demanding that the Gaza-based Hamas resistance movement pay taxes on fuel imports to the coastal strip. 2. Fatah official assassinated by car bomb in Lebanon (12.4.2016) Source: Al-Arabiyah Palestine News Forum 6/4-12/4/16 Palestine News Forum 6/4-12/4/16 A car bomb explodes near a Palestinian refugee camp in southern Lebanese port city of Sidon, killing at least one person and injuring two others. The man was identified as Fathi Zaydan, who headed the Palestinian Fatah movement in the Miye Miye Palestinian refugee camp near Sidon. A Fatah official said the man was killed by a bomb placed under his vehicle. The Lebanese army's forensics unit arrived at the scene of the blast and cleared away scorched body parts lying near a car in flames. The Miyeh Miyeh camp, 4 km east of Sidon, is home to 5,250 Palestinian refugees, ac- cording to UN Relief and Works Agency (UNRWA) figures. -

A Christian's Map of the Holy Land

A CHRISTIAN'S MAP OF THE HOLY LAND Sidon N ia ic n e o Zarefath h P (Sarepta) n R E i I T U A y r t s i Mt. of Lebanon n i Mt. of Antilebanon Mt. M y Hermon ’ Beaufort n s a u b s s LEGEND e J A IJON a H Kal'at S Towns visited by Jesus as I L e o n Nain t e s Nimrud mentioned in the Gospels Caesarea I C Philippi (Banias, Paneas) Old Towns New Towns ABEL BETH DAN I MA’ACHA T Tyre A B a n Ruins Fortress/Castle I N i a s Lake Je KANAH Journeys of Jesus E s Pjlaia E u N s ’ Ancient Road HADDERY TYRE M O i REHOB n S (ROSH HANIKRA) A i KUNEITRA s Bar'am t r H y s u Towns visited by Jesus MISREPOTH in K Kedesh sc MAIM Ph a Sidon P oe Merom am n HAZOR D Tyre ic o U N ACHZIV ia BET HANOTH t Caesarea Philippi d a o Bethsaida Julias GISCALA HAROSH A R Capernaum an A om Tabgha E R G Magdala Shave ACHSAPH E SAFED Zion n Cana E L a Nazareth I RAMAH d r Nain L Chorazin o J Bethsaida Bethabara N Mt. of Beatitudes A Julias Shechem (Jacob’s Well) ACRE GOLAN Bethany (Mt. of Olives) PISE GENES VENISE AMALFI (Akko) G Capernaum A CABUL Bethany (Jordan) Tabgha Ephraim Jotapata (Heptapegon) Gergesa (Kursi) Jericho R 70 A.D. Magdala Jerusalem HAIFA 1187 Emmaus HIPPOS (Susita) Horns of Hittin Bethlehem K TIBERIAS R i Arbel APHEK s Gamala h Sea of o Atlit n TARICHAFA Galilee SEPPHORIS Castle pelerin Y a r m u k E Bet Tsippori Cana Shearim Yezreel Valley Mt. -

Three Conquests of Canaan

ÅA Wars in the Middle East are almost an every day part of Eero Junkkaala:of Three Canaan Conquests our lives, and undeniably the history of war in this area is very long indeed. This study examines three such wars, all of which were directed against the Land of Canaan. Two campaigns were conducted by Egyptian Pharaohs and one by the Israelites. The question considered being Eero Junkkaala whether or not these wars really took place. This study gives one methodological viewpoint to answer this ques- tion. The author studies the archaeology of all the geo- Three Conquests of Canaan graphical sites mentioned in the lists of Thutmosis III and A Comparative Study of Two Egyptian Military Campaigns and Shishak and compares them with the cities mentioned in Joshua 10-12 in the Light of Recent Archaeological Evidence the Conquest stories in the Book of Joshua. Altogether 116 sites were studied, and the com- parison between the texts and the archaeological results offered a possibility of establishing whether the cities mentioned, in the sources in question, were inhabited, and, furthermore, might have been destroyed during the time of the Pharaohs and the biblical settlement pe- riod. Despite the nature of the two written sources being so very different it was possible to make a comparative study. This study gives a fresh view on the fierce discus- sion concerning the emergence of the Israelites. It also challenges both Egyptological and biblical studies to use the written texts and the archaeological material togeth- er so that they are not so separated from each other, as is often the case. -

Retail Prices in a City*

Retail Prices in a City Alon Eizenberg Saul Lach The Hebrew University and CEPR The Hebrew University and CEPR Merav Yiftach Israel Central Bureau of Statistics July 2017 Abstract We study grocery price differentials across neighborhoods in a large metropolitan area (the city of Jerusalem, Israel). Prices in commercial areas are persistently lower than in residential neighborhoods. We also observe substantial price variation within residential neighborhoods: retailers that operate in peripheral, non-a uent neighborhoods charge some of the highest prices in the city. Using CPI data on prices and neighborhood-level credit card data on expenditure patterns, we estimate a model in which households choose where to shop and how many units of a composite good to purchase. The data and the estimates are consistent with very strong spatial segmentation. Combined with a pricing equation, the demand estimates are used to simulate interventions aimed at reducing the cost of grocery shopping. We calculate the impact on the prices charged in each neighborhood and on the expected price paid by its residents - a weighted average of the prices paid at each destination, with the weights being the probabilities of shopping at each destination. Focusing on prices alone provides an incomplete picture and may even be misleading because shopping patterns change considerably. Specifically, we find that interventions that make the commercial areas more attractive and accessible yield only minor price reductions, yet expected prices decrease in a pronounced fashion. The benefits are particularly strong for residents of the peripheral, non-a uent neighborhoods. We thank Eyal Meharian and Irit Mishali for their invaluable help with collecting the price data and with the provision of the geographic (distance) data. -

Itinerary Is Subject to Change. •

Itinerary is Subject to Change. • Welcome to Israel! Upon arrival, transfer to the Carlton Hotel in Tel Aviv. At 7:30 pm, enjoy a special welcome dinner at Blue Sky restaurant by Chef Meir Adoni, located on the rooftop of the hotel. After a warm welcome from the mission chairs, hear an overview of the upcoming days and learn more about JNF’s Women for Israel group. Tel Aviv Overnight, Carlton Hotel, Tel Aviv • Early this morning, everyone is invited to join optional yoga class on the beach. Following breakfast, participate in a special workshop that will provide an Yoga on the Beach introduction to the mission and the women on the trip. Depart the hotel for the Alexander Muss High School in Israel (AMHSI), the only non- denominational, pluralistic, accredited academic program in Israel for English speaking North American High School students. Following a tour, meet school administrators several students, who will share their experiences from the program. Join them at the new AMHSI Ben-Dor Radio Station for a special activity. AMHSI students Afterward, enjoy lunch at a local restaurant in Tel Aviv. Hear from top Israeli reporter, investigative journalist and anchorwoman Ilana Dayan, who will provide an update on the current social, political and cultural issues shaping Israel. This afternoon, enjoy a walking tour through Old Jaffa, an 8000-year-old port city. Walk through the winding alleyways, stop at the ancient ruins and explore the restored artist's quarter. Continue to the Ilana Goor Museum, an ever-changing, living exhibition that houses over 500 works of art by Ilana Goor and other celebrated artists. -

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005 BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights i BADIL is a member of the Global Palestine Right of Return Coalition Preface The Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons is published annually by BADIL Resource Center. The Survey provides an overview of one of the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee and displaced populations in the world today. It is estimated that two out of every five of today’s refugees are Palestinian. The Survey has several objectives: (1) It aims to provide basic information about Palestinian displacement – i.e., the circumstances of displacement, the size and characteristics of the refugee and displaced population, as well as the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons; (2) It aims to clarify the framework governing protection and assistance for this displaced population; and (3) It sets out the basic principles for crafting durable solutions for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, consistent with international law, relevant United Nations Resolutions and best practice. In short, the Survey endeavors to address the lack of information or misinformation about Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, and to counter political arguments that suggest that the issue of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons can be resolved outside the realm of international law and practice applicable to all other refugee and displaced populations. The Survey examines the status of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons on a thematic basis. Chapter One provides a short historical background to the root causes of Palestinian mass displacement. -

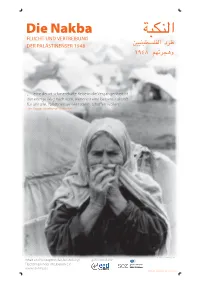

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

Journal of an Ordinary Grief’ by Mahmoud Darwish

LiNGUA Vol. 13, No. 2, December 2018 • ISSN 1693-4725 • e-ISSN 2442-3823 THEMES AND WRITING TECHNIQUES OF ‘JOURNAL OF AN ORDINARY GRIEF’ BY MAHMOUD DARWISH Akram Roshanfekr & Fahime Mousavi [email protected] University of Guilan Rasht, Iran Abstract: Today, writing biography in literature is accompanied by some advancement, namely autobiography. Mostly autobiographies imply the purpose of the writer containing several writing types including historiography, counting the days, memory writing, reportage, story writing, or travel writing. They also use techniques such as dialogue and description in order to involve the reader in the course of his life events happened. This study employs a descriptive-analytic method to ‘Journal of an Ordinary Grief’ by Mahmoud Darwish for examining its autobiographical themes and techniques. The most important result of the current study is that seven different writing techniques were applied in ‘Journal of an Ordinary Grief’. Darwish used report writing and interview method in narrating interrogations, and in this way, he presented more information about the contact style of hostile forces and their oral literature for his work's reader access. It considers the development of content in describing his life events by which he has produced a social-political autobiography. Keywords: autobiography, Mahmoud Darwish. INTRODUCTION and the manner of their usage from biography The description of literate's life of writing techniques in ‘Journal of an Ordinary oneself is a kind of literary work that literates Grief’ is presented. and men of science and art have considered it In describing the research background, and have produced a text called Fan ‘al-Sire' by Ehsan Abbas published in ‘autobiography' (Shamisa, 1996, p. -

Colonialism, Colonization, and Land Law in Mandate Palestine: the Zor Al-Zarqa and Barrat Qisarya Land Disputes in Historical Perspective

Theoretical Inquiries in Law 4.2 (2003) Colonialism, Colonization, and Land Law in Mandate Palestine: The Zor al-Zarqa and Barrat Qisarya Land Disputes in Historical Perspective Geremy Forman & Alexandre Kedar* This articlefocuses on land rights, land law, and land administration within a multilayered colonial setting by examining a major land dispute in British-ruled Palestine (1917-1948). Our research reveals that the Mandate legal system extinguished indigenous rights to much land in the Zor al-Zarqa and Barrat Qisarya regions through its use of "colonial law"- the interpretation of Ottoman law by colonial officials, the use of foreign legal concepts, and the transformation of Ottoman law through supplementary legislation.However the colonial legal system was also the site of local resistance by some Palestinian Arabs attempting to remain on their land in the face of the pressure of the Mandate authorities and Jewish colonization officials. This article sheds light on the dynamics of the Mandate legal system and colonial law in the realm of land tenure relations.It also suggests that the joint efforts of Mandate and Jewish colonization officials to appropriate Geremy Forman is a Ph.D. candidate in the University of Haifa's Department of Land of Israel Studies. Alexandre (Sandy) Kedar is a Lecturer in the University of Haifa's Faculty of Law. Names of authors by alphabetical order. We would like to thank Oren Yiftachel for his contribution to this article and Michael Fischbach for his insightful remarks and suggestions. We are also grateful to Assaf Likhovsky for his feedback and constructive criticism, to Anat Fainstein for her research assistance, and to Dana Rothman of Theoretical Inquiries in Law for her expert editorial advice. -

Graduate Center. Spring 2018. Doctoral Program in History

1 City University of New York – Graduate Center. Spring 2018. Doctoral Program in History/Master’s Program in Middle Eastern Studies Room: Course Number: HIST 78110/MES 74500 Tuesday: 6:30 – 8:30 PM. Course Instructor: Simon Davis, [email protected] Office Phone: (718) 289 5677. Palestine Under The British Mandate: Origins, Evolutions and Implications, 1906-1949. This course examines how and with what consequences British interests at the time of the First World War identified and pursued control over Palestine, the subsequent forms such projections took, the crises which followed and their eventual consequences. Particular themes will be explored through analytical discussions of assigned historiographic materials, chiefly recent journal literature. Learning Objectives: Students will be encouraged to evaluate still-contested historical phenomena such as British undertakings with Zionism, colonialist relationships with Arab Palestine, institution-making and economic development, social and cultural transformations, resistance and political violence. This will be understood in the broader context of Middle Eastern politics in the era of late European colonial imperialism. Consonant and particular local experience in Palestine will also be addressed, exploring the effect of British Mandatory administration, especially in ethnic and sectarian-inflected questions of status, social and material conditions, identity, community, law and justice, expression and political rights. Finally, how and why did the Mandate end in a British debacle, Zionist triumph and Arab Palestinian catastrophe, with what main legacies resulting? On the basis of these studies students will each complete a research essay from the list below, along with a number of smaller critical exercises, and a final examination.