Deir Yassin Continues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campaign to Preserve Mamilla Jerusalem Cemetery

PETITION FOR URGENT ACTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY ISRAEL Campaign to Preserve Mamilla Jerusalem Cemetery www.mamillacampaign.org Copyright 2010 by Campaign to Preserve Mamilla Jerusalem Cemetery www.mammillacampaign.org PETITION FOR URGENT ACTION ON HUMAN RIGHTS VIOLATIONS BY ISRAEL: DESECRATION OF THE MA’MAN ALLAH (MAMILLA) MUSLIM CEMETERY IN THE HOLY CITY OF JERUSALEM TO: 1.The United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights (Ms. Navi Pillay) 2. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion and Belief (Ms. Asma Jahangir) 3. The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Contemporary Forms of Racism, Racial Discrimination, Xenophobia and Related Intolerance (Mr. Githu Muigai) 4. The United Nations Independent Expert in the Field of Cultural Rights (Ms. Farida Shaheed) 5. Director-General of United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization (Ms. Irina Bokova) 6. The Government of Switzerland in its capacity as depository of the Fourth Geneva Conventions INDIVIDUAL PETITIONERS: Sixty individuals whose ancestors are interred in Mamilla (Ma’man Allah) Cemetery, from the Jerusalem families of: 1. Akkari 2. Ansari 3. Dajani 4. Duzdar 5. Hallak 6. Husseini 7. Imam 8. Jaouni 9. Khalidi 10. Koloti 11. Kurd 12. Nusseibeh 13. Salah 14. Sandukah 15. Zain CO- PETITIONERS: 1. Mustafa Abu-Zahra, Mutawalli of Ma’man Allah Cemetery 2. Addameer Prisoner Support and Human Rights Association 3. Al-Mezan Centre for Human Rights 4. Al-Dameer Association for Human Rights 5. Al-Haq 6. Al-Quds Human Rights Clinic 7. Arab Association for Human Rights (HRA) 8. Association for the Defense of the Rights of the Internally Displaced in Israel (ADRID) 9. -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

Zochrot Annual Report 2019 January 2020

Zochrot Annual Report 2019 January 2020 1 Opening As can be clearly shown in the report below, Zochrot activity and public outreach had increased significantly in 2019. During the time of the report, January 2019 – December 2019 we had carried out more than 60 different activities in public sphere including tours to destroyed Palestinian localities, lectures, symposiums, workshops, exhibition, educational courses, film festival, direct actions and more, all designed to make the Nakba present in public spaces, to resist the ongoing Nakba, and to oppose the mechanisms of denial and erasure. We continue to call upon Israelis to acknowledge their responsibility for the Nakba and to uphold justice by supporting Palestinian return. Over 2,400 people participated in our activities over the past year and took an active part in discussion about the Nakba and return. This year we also reached almost 100,000 visitors on our websites, which continues to be a leading resource to many people all over the world about the Nakba and the Return. About Zochrot Zochrot ("remembering" in Hebrew) is a grassroots NGO working since 2002 in Palestine-Israel to promote acknowledgement of and accountability for the ongoing injustices of the Nakba, the Palestinian catastrophe of 1948. Zochrot works towards the reconceptualization of the right of return as the imperative redress of the Nakba and a chance for a better life for all the country's inhabitants. Zochrot is the first and major Israeli nonprofit organization and growing movement devoted to the commemoration of the Nakba and for advocating for Palestinian return, first and foremost among the Jewish Israeli majority in Israel. -

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005 BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights i BADIL is a member of the Global Palestine Right of Return Coalition Preface The Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons is published annually by BADIL Resource Center. The Survey provides an overview of one of the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee and displaced populations in the world today. It is estimated that two out of every five of today’s refugees are Palestinian. The Survey has several objectives: (1) It aims to provide basic information about Palestinian displacement – i.e., the circumstances of displacement, the size and characteristics of the refugee and displaced population, as well as the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons; (2) It aims to clarify the framework governing protection and assistance for this displaced population; and (3) It sets out the basic principles for crafting durable solutions for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, consistent with international law, relevant United Nations Resolutions and best practice. In short, the Survey endeavors to address the lack of information or misinformation about Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, and to counter political arguments that suggest that the issue of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons can be resolved outside the realm of international law and practice applicable to all other refugee and displaced populations. The Survey examines the status of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons on a thematic basis. Chapter One provides a short historical background to the root causes of Palestinian mass displacement. -

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

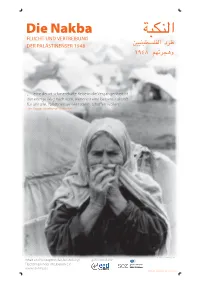

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

Profiles of Peace

Profiles of Peace Forty short biographies of Israeli and Palestinian peace builders who have struggled to end the occupation and build a just future for both Palestinians and Israelis. Haidar Abdel Shafi Palestinian with a long history of working to improve the health and social conditions of Palestinians and the creation of a Palestinian state. Among his many accomplishments, Dr. Abdel Shafi has been the director of the Red Crescent Society of Gaza, was Chairman of the first Palestinian Council in Gaza, and took part in the Madrid Peace Talks in 1991. Dr. Haidar Abdel Shafi is one of the most revered persons in Palestine, whose long life has been devoted to the health and social conditions of his people and to their aspirations for a national state. Born in Gaza in 1919, he has spent most of his life there, except for study in Lebanon and the United States. He has been the director of the Red Crescent Society in Gaza and has served as Commissioner General of the Palestinian Independent Commission for Citizens Rights. His passion for an independent state of Palestine is matched by his dedication to achieve unity among all segments of the Palestinian community. Although Gaza is overwhelmingly religiously observant, he has won and kept the respect and loyalty of the people even though he himself is secular. Though nonparti- san he has often been associated with the Palestinian left, especially with the Palestinian Peoples Party (formerly the Palestinian Communist Party). A mark of his popularity is his service as Chairman of the first Palestinian Council in Gaza (1962-64) and his place on the Executive Committee of “There is no problem of the Palestinian Liberation Organization (PLO) (1964-65). -

Trauma and the Palestinian Nakba

Trauma and the Palestinian Nakba Submitted by Nicholas Peddle to the University of Exeter as a dissertation for the degree of MA Middle East and Islamic Studies September 2015 1 I certify that all material in this dissertation which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. 2 Abstract This dissertation investigates the traumatic consequences of the Palestinian Nakba based upon six interviews conducted with Palestinians living within Israel during the summer of 2015. It is the use of a psychoanalytic theory of transgenerational transmission of trauma which describes the effects of trauma on an individual witness and the percussive effects on their children and their children’s children. The focus of this work is studying the path which trauma, from its inception in the events of the Nakba, weaves through the lives of Palestinians and the subsequent effect on their interactions with the external world. My research on such a phenomenon was motivated by an understanding of the psychological concepts and a deep interest in the persistent crisis facing the Palestinian people. The work is guided by various research questions; what impact has trauma had on the lives of those who experienced the Nakba? Can psychoanalytic concepts enable a deeper understanding of their suffering? Does such a suffering still exert an influence over the lives of contemporary Palestinians and exactly how and to what effect are these influences felt? The Palestinian Nakba occupies a powerful position in many fields, politics, anthropology, literature, memory work, but is almost totally absent from trauma study. -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Over Palestine

Metula Majdal Shams Abil al-Qamh ! Neve Ativ Misgav Am Yuval Nimrod ! Al-Sanbariyya Kfar Gil'adi ZZ Ma'ayan Baruch ! MM Ein Qiniyye ! Dan Sanir Israeli Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid over Palestine Al-Sanbariyya DD Al-Manshiyya ! Dafna ! Mas'ada ! Al-Khisas Khan Al-Duwayr ¥ Huneen Al-Zuq Al-tahtani ! ! ! HaGoshrim Al Mansoura Margaliot Kiryat !Shmona al-Madahel G GLazGzaGza!G G G ! Al Khalsa Buq'ata Ethnic Cleansing and Population Transfer (1948 – present) G GBeGit GHil!GlelG Gal-'A!bisiyya Menara G G G G G G G Odem Qaytiyya Kfar Szold In order to establish exclusive Jewish-Israeli control, Israel has carried out a policy of population transfer. By fostering Jewish G G G!G SG dGe NG ehemia G AGl-NGa'iGmaG G G immigration and settlements, and forcibly displacing indigenous Palestinians, Israel has changed the demographic composition of the ¥ G G G G G G G !Al-Dawwara El-Rom G G G G G GAmG ir country. Today, 70% of Palestinians are refugees and internally displaced persons and approximately one half of the people are in exile G G GKfGar GB!lGumG G G G G G G SGalihiya abroad. None of them are allowed to return. L e b a n o n Shamir U N D ii s e n g a g e m e n tt O b s e rr v a tt ii o n F o rr c e s Al Buwayziyya! NeoG t MG oGrdGecGhaGi G ! G G G!G G G G Al-Hamra G GAl-GZawG iyGa G G ! Khiyam Al Walid Forcible transfer of Palestinians continues until today, mainly in the Southern District (Beersheba Region), the historical, coastal G G G G GAl-GMuGftskhara ! G G G G G G G Lehavot HaBashan Palestinian towns ("mixed towns") and in the occupied West Bank, in particular in the Israeli-prolaimed “greater Jerusalem”, the Jordan G G G G G G G Merom Golan Yiftah G G G G G G G Valley and the southern Hebron District. -

Medinas 2030˝ Exhibition the Catalogue

˝Medinas 2030˝ exhibition The Catalogue FEMIP for the Mediterranean 2 ˝Medinas 2030˝ exhibition Introduction Welcome to the ˝Medinas 2030˝ Exhibition At the end of 2008, at the Venice Biennale International Architecture Exhibi- always useful and often successful, are presented in this brochure for the tion, the European Investment Bank inaugurated its “Medinas 2030” initiative. Medinas 2030 exhibition. It was in that context and in order to raise public awareness of the impor- These initiatives have, however, highlighted the usefulness of preparing tance of renovating the ancient city centres of the Mediterranean that I a sustainable regeneration strategy that can be extended to each of the decided to launch a travelling exhibition on the challenges and experi- Mediterranean partner countries, with the adjustments required by local ences of successful regeneration projects in the Mediterranean. circumstances. In this way the EIB hopes to improve the responses that can be given to the This will make it possible to step up investment programmes to improve ongoing process of economic and social decline that, for several decades, the quality of life of the inhabitants, while preserving the cultural value of has been affecting the historic centres of towns in the Mediterranean. these irreplaceable sites. This trend is the result of irreversible changes associated with the influx of I am therefore delighted to invite you on this “cultural trip” through a people from the countryside and the new competition between urban areas selection of ancient Mediterranean cities. They are not all, strictly speaking, that is being accelerated by the globalisation of our economies. The respons- ‘’medinas’’, but the way in which they have developed and their richness es that can be provided are complex and therefore difficult to implement, as in terms of heritage mean that they have a shared Mediterranean kinship Philippe de Fontaine Vive the preservation of these precious but fragile assets must take account of and their regeneration deserves your attention. -

Report Truth Commission on the Responsibility of Israeli Society For

Report Truth Commission on the Responsibility of Israeli Society for the Events of 1948-1960 in the South تق رير جلنة احلقيقة حول مسؤولية املجمتع اﻹرسائ ي ّيل عن أحداث 1960-1948 يف ّجنويب البﻻد December 2015 www. zochrot.org צילום אוויר באר שבע 1946 Beersheba, Aerial photo, 1946 photo, Aerial Beersheba, Truth Commission on the Responsibility of Israeli Society for the Events of 1948-1960 in the South FINAL REPORT: ENGLISH DIGEST March 2016 Editing: Jessica Nevo, Tammy Pustilnick and Ami Asher Language editing and translations: Ami Asher Cover design: Nirit Binyamin and Gila Kaplan Graphic design: Tali Eisner Friedman, Noa Olchovsky Printing: Hashlama Print Production: Zochrot (580389526) Yitzhak Sade 34 Tel Aviv-Jaffa Tel 03-6953155 Fax 03-6953154 (C) All rights reserved to those who were expelled from their homes 2 Contents: Introduction: Transitional Justice without Transition - The First Truth Commission on the Nakba Tammy Pustilnick & Jessica Nevo - Zochrot / p. 4 1. Model Rationale and Development / p. 7 2. Expert Testimony: The Conflict Shoreline - Climate Change as Colonization in the Negev Prof. Eyal Weizman, Goldsmiths, University of London / p. 11 3. Circles of Silence: On the Difficulties of Collecting Testimonies from Jewish Fighters in 1948 Ami Asher, Zochrot / p. 14 4. Testimonies / p. 19 4.1 Excerpts from Testimonies of Jewish Fighters 4.2 Testimonies by Bedouin Palestinian Refugees 5. Recommendations / p. 26 Thank you to all the witnesses Thank you to the Bedouin Palestinian activists resisting the impact of the Nakba to this day Thank you to the experts who have testified before the Commission: Dr. -

How to Say 'Awda in Hebrew?

Zochrot invites: How to say 'Awda in Hebrew? The Third International Conference on the Return of Palestinian Refugees Monday, March 21, 2016 9:30 Registration Visibility, Documentation, Testimony and the Big Elephant Yudit Ilany sociopolitical activist and freelance documentarist; 10:00 Opening address photojournalist and correspondent for the Israel Social TV; parliamentary advisor for Member of Knesset Haneen Zoabi 10:15 Keynote speaker: Prof. Ilan Pappé Practical Return in Palestinian Civil Society: Challenges Imagining the Post-Return Space and Opportunities Prof. Ilan Pappé Haifa-born historian, University of Exeter, UK Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights, Bethlehem 11:00 The current situation of Palestinian refugees Badil Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee The Intensified Political Activism to Promote Return in Rights, Bethlehem Palestinian Society Within 1948 Nadim Nashif Director of Baladna, Association for Arab Youth, Haifa 11:30 Coffee break Q&A :״Thy children shall come again to their own border״ 12:00 Learning from refugee returns in the world 16:00 Coffee break Chair: Dr. Anat Leibler A fellow of the Science, Numbers and 16:30 Between Mizrahim and Palestinians: The Tension Politics research project, the Heidelberg Academy of Sciences Between Exclusion and Responsibility and Humanities Chair: Dr. Tom Pessah–Yonatan Shapira postdoctoral fellow at the Lessons learned from :״They are doing it for themselves״ Dept. of Sociology and Anthropology, Tel Aviv University Self-Organized Return in post-war Bosnia and Herzegovina Dr. Selma Porobić Activist and Forced Migration scholar, Director Ashkenazi Privileges, the Nakba and the Mizrahim Centre for refugee and IDP studies, University of Sarajevo Tom Mehager Mizrahi activist and blogger at Haoketz website Repatriation and Reintegration: Lessons from Rwanda The Mizrahim and the Nakba: Analyzing the Problematic Justine Mbabazi Rukeba International lawyer and development Conjunction practitioner, expert in transitional justice, peace and security, and Dr.