Deir Yassin: History of a Lie

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jews on Route to Palestine 1934-1944. Sketches from the History of Aliyah

JEWS ON ROUTE TO PALESTINE 1934−1944 JAGIELLONIAN STUDIES IN HISTORY Editor in chief Jan Jacek Bruski Vol. 1 Artur Patek JEWS ON ROUTE TO PALESTINE 1934−1944 Sketches from the History of Aliyah Bet – Clandestine Jewish Immigration Jagiellonian University Press Th e publication of this volume was fi nanced by the Jagiellonian University in Krakow – Faculty of History REVIEWER Prof. Tomasz Gąsowski SERIES COVER LAYOUT Jan Jacek Bruski COVER DESIGN Agnieszka Winciorek Cover photography: Departure of Jews from Warsaw to Palestine, Railway Station, Warsaw 1937 [Courtesy of National Digital Archives (Narodowe Archiwum Cyfrowe) in Warsaw] Th is volume is an English version of a book originally published in Polish by the Avalon, publishing house in Krakow (Żydzi w drodze do Palestyny 1934–1944. Szkice z dziejów alji bet, nielegalnej imigracji żydowskiej, Krakow 2009) Translated from the Polish by Guy Russel Torr and Timothy Williams © Copyright by Artur Patek & Jagiellonian University Press First edition, Krakow 2012 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any eletronic, mechanical, or other means, now know or hereaft er invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers ISBN 978-83-233-3390-6 ISSN 2299-758X www.wuj.pl Jagiellonian University Press Editorial Offi ces: Michałowskiego St. 9/2, 31-126 Krakow Phone: +48 12 631 18 81, +48 12 631 18 82, Fax: +48 12 631 18 83 Distribution: Phone: +48 12 631 01 97, Fax: +48 12 631 01 98 Cell Phone: + 48 506 006 674, e-mail: [email protected] Bank: PEKAO SA, IBAN PL80 1240 4722 1111 0000 4856 3325 Contents Th e most important abbreviations and acronyms ........................................ -

Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs Between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948

[Intelligence Service (Arab Section)] June 30, 1948 Migration of Eretz Yisrael Arabs between December 1, 1947 and June 1, 1948 Contents 1. General introduction. 2. Basic figures on Arab migration 3. National phases of evacuation and migration 4. Causes of Arab migration 5. Arab migration trajectories and absorption issues Annexes 1. Regional reviews analyzing migration issues in each area [Missing from document] 2. Charts of villages evacuated by area, noting the causes for migration and migration trajectories for every village General introduction The purpose of this overview is to attempt to evaluate the intensity of the migration and its various development phases, elucidate the different factors that impacted population movement directly and assess the main migration trajectories. Of course, given the nature of statistical figures in Eretz Yisrael in general, which are, in themselves, deficient, it would be difficult to determine with certainty absolute numbers regarding the migration movement, but it appears that the figures provided herein, even if not certain, are close to the truth. Hence, a margin of error of ten to fifteen percent needs to be taken into account. The figures on the population in the area that lies outside the State of Israel are less accurate, and the margin of error is greater. This review summarizes the situation up until June 1st, 1948 (only in one case – the evacuation of Jenin, does it include a later occurrence). Basic figures on Arab population movement in Eretz Yisrael a. At the time of the UN declaration [resolution] regarding the division of Eretz Yisrael, the following figures applied within the borders of the Hebrew state: 1. -

4.Employment Education Hebrew Arnona Culture and Leisure

Did you know? Jerusalem has... STARTUPS OVER OPERATING IN THE CITY OVER SITES AND 500 SYNAGOGUES 1200 39 MUSEUMS ALTITUDE OF 630M CULTURAL INSTITUTIONS COMMUNITY 51 AND ARTS CENTERS 27 MANAGERS ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem ( ) Aliyah2Jerusalem JERUSALEM IS ISRAEL’S STUDENTS LARGEST CITY 126,000 DUNAM Graphic design by OVER 40,000 STUDYING IN THE CITY 50,000 VOLUNTEERS Illustration by www.rinatgilboa.com • Learning centers are available throughout the city at the local Provide assistance for olim to help facilitate a smooth absorption facilities. The centers offer enrichment and study and successful integration into Jerusalem. programs for school age children. • Jerusalem offers a large selection of public and private schools Pre - Aliyah Services 2 within a broad religious spectrum. Also available are a broad range of learning methods offered by specialized schools. Assistance in registration for municipal educational frameworks. Special in Jerusalem! Assistance in finding residence, and organizing community needs. • Tuition subsidies for Olim who come to study in higher education and 16 Community Absorption Coordinators fit certain criteria. Work as a part of the community administrations throughout the • Jerusalem is home to more than 30 institutions of higher education city; these coordinators offer services in educational, cultural, sports, that are recognized by the Student Authority of the Ministry of administrative and social needs for Olim at the various community Immigration & Absorption. Among these schools is Hebrew University – centers. -

Retail Prices in a City*

Retail Prices in a City Alon Eizenberg Saul Lach The Hebrew University and CEPR The Hebrew University and CEPR Merav Yiftach Israel Central Bureau of Statistics July 2017 Abstract We study grocery price differentials across neighborhoods in a large metropolitan area (the city of Jerusalem, Israel). Prices in commercial areas are persistently lower than in residential neighborhoods. We also observe substantial price variation within residential neighborhoods: retailers that operate in peripheral, non-a uent neighborhoods charge some of the highest prices in the city. Using CPI data on prices and neighborhood-level credit card data on expenditure patterns, we estimate a model in which households choose where to shop and how many units of a composite good to purchase. The data and the estimates are consistent with very strong spatial segmentation. Combined with a pricing equation, the demand estimates are used to simulate interventions aimed at reducing the cost of grocery shopping. We calculate the impact on the prices charged in each neighborhood and on the expected price paid by its residents - a weighted average of the prices paid at each destination, with the weights being the probabilities of shopping at each destination. Focusing on prices alone provides an incomplete picture and may even be misleading because shopping patterns change considerably. Specifically, we find that interventions that make the commercial areas more attractive and accessible yield only minor price reductions, yet expected prices decrease in a pronounced fashion. The benefits are particularly strong for residents of the peripheral, non-a uent neighborhoods. We thank Eyal Meharian and Irit Mishali for their invaluable help with collecting the price data and with the provision of the geographic (distance) data. -

Itinerary Is Subject to Change. •

Itinerary is Subject to Change. • Welcome to Israel! Upon arrival, transfer to the Carlton Hotel in Tel Aviv. At 7:30 pm, enjoy a special welcome dinner at Blue Sky restaurant by Chef Meir Adoni, located on the rooftop of the hotel. After a warm welcome from the mission chairs, hear an overview of the upcoming days and learn more about JNF’s Women for Israel group. Tel Aviv Overnight, Carlton Hotel, Tel Aviv • Early this morning, everyone is invited to join optional yoga class on the beach. Following breakfast, participate in a special workshop that will provide an Yoga on the Beach introduction to the mission and the women on the trip. Depart the hotel for the Alexander Muss High School in Israel (AMHSI), the only non- denominational, pluralistic, accredited academic program in Israel for English speaking North American High School students. Following a tour, meet school administrators several students, who will share their experiences from the program. Join them at the new AMHSI Ben-Dor Radio Station for a special activity. AMHSI students Afterward, enjoy lunch at a local restaurant in Tel Aviv. Hear from top Israeli reporter, investigative journalist and anchorwoman Ilana Dayan, who will provide an update on the current social, political and cultural issues shaping Israel. This afternoon, enjoy a walking tour through Old Jaffa, an 8000-year-old port city. Walk through the winding alleyways, stop at the ancient ruins and explore the restored artist's quarter. Continue to the Ilana Goor Museum, an ever-changing, living exhibition that houses over 500 works of art by Ilana Goor and other celebrated artists. -

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005

Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons 2004 - 2005 BADIL Resource Center for Palestinian Residency & Refugee Rights i BADIL is a member of the Global Palestine Right of Return Coalition Preface The Survey of Palestinian Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons is published annually by BADIL Resource Center. The Survey provides an overview of one of the largest and longest-standing unresolved refugee and displaced populations in the world today. It is estimated that two out of every five of today’s refugees are Palestinian. The Survey has several objectives: (1) It aims to provide basic information about Palestinian displacement – i.e., the circumstances of displacement, the size and characteristics of the refugee and displaced population, as well as the living conditions of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons; (2) It aims to clarify the framework governing protection and assistance for this displaced population; and (3) It sets out the basic principles for crafting durable solutions for Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, consistent with international law, relevant United Nations Resolutions and best practice. In short, the Survey endeavors to address the lack of information or misinformation about Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons, and to counter political arguments that suggest that the issue of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons can be resolved outside the realm of international law and practice applicable to all other refugee and displaced populations. The Survey examines the status of Palestinian refugees and internally displaced persons on a thematic basis. Chapter One provides a short historical background to the root causes of Palestinian mass displacement. -

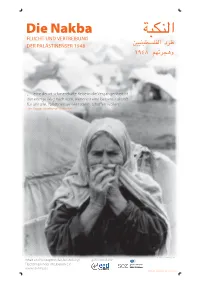

Die Nakba – Flucht Und Vertreibung Der Palästinenser 1948

Die Nakba FLUCHT UND VERTREIBUNG DER PALÄSTINENSER 1948 „… eine derart schmerzhafte Reise in die Vergangenheit ist der einzige Weg nach vorn, wenn wir eine bessere Zukunft für uns alle, Palästinenser wie Israelis, schaffen wollen.“ Ilan Pappe, israelischer Historiker Gestaltung: Philipp Rumpf & Sarah Veith Inhalt und Konzeption der Ausstellung: gefördert durch Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. www.lib-hilfe.de © Flüchtlingskinder im Libanon e.V. 1 VON DEN ERSTEN JÜDISCHEN EINWANDERERN BIS ZUR BALFOUR-ERKLÄRUNG 1917 Karte 1: DER ZIONISMUS ENTSTEHT Topographische Karte von Palästina LIBANON 01020304050 km Die Wurzeln des Palästina-Problems liegen im ausgehenden 19. Jahrhundert, als Palästina unter 0m Akko Safed SYRIEN Teil des Osmanischen Reiches war. Damals entwickelte sich in Europa der jüdische Natio- 0m - 200m 200m - 400m Haifa 400m - 800m nalismus, der so genannte Zionismus. Der Vater des politischen Zionismus war der öster- Nazareth reichisch-ungarische Jude Theodor Herzl. Auf dem ersten Zionistenkongress 1897 in Basel über 800m Stadt wurde die Idee des Zionismus nicht nur auf eine breite Grundlage gestellt, sondern es Jenin Beisan wurden bereits Institutionen ins Leben gerufen, die für die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina werben und sie organisieren sollten. Tulkarm Qalqilyah Nablus MITTELMEER Der Zionismus war u.a. eine Antwort auf den europäischen Antisemitismus (Dreyfuß-Affäre) und auf die Pogrome vor allem im zaristischen Russ- Jaffa land. Die Einwanderung von Juden nach Palästina erhielt schon frühzeitig einen systematischen, organisatorischen Rahmen. Wichtigste Institution Lydda JORDANIEN Ramleh Ramallah wurde der 1901 gegründete Jüdische Nationalfond, der für die Anwerbung von Juden in aller Welt, für den Ankauf von Land in Palästina, meist von Jericho arabischen Großgrundbesitzern, und für die Zuteilung des Bodens an die Einwanderer zuständig war. -

ISRAELI TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE to AFRICA a Thesis ,Presented In

ISRAELI TECHNICAL ASSISTANCE TO AFRICA A Thesis ,Presented in Partial Fulfill.rn.ent of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts }f y Elton Roger Trent, B.A. and B.S. in Ed. The Ohio State University 196L Approved by FOREWARD I became interested in the problems of underdeveloped nations .and territories in the course, Africa and the Western World in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, given by Professor Lowell Ragatz, and pursued the subject fu:".'ther in The Middle East Since 1914, taught by Professor Sydney Fisher. At the latter 1 s suggestion, I began searching for materials on Israel 1 s tech~ical assistance to Africa and became much engrossed in it. When one reads widely on this subject, several questions come to mind. Why, for example, did Israel, a small, newly inde pendent nation, offer assistance to tbs new nations and territories of Africa? On the other hand, why did such African nations accept this aid so readily? What were the reactions of the Arab nations? Of the West? Of the Sino-Soviet Bloc? Of underdeveloped nations in general? Of Israel? What will be Israel's future in "Black Africa"? Data will be presented and conclusions drawn in answer to each of these questions. November JO, 1964 Elton R. Trent ii CONTEN'l'S Page FOREWARD . ii Chapter I THE HISTORICAL B~CKGRODND . 1 II A MISSION OF GOODWILL • • . 28 III HOMA.NISM OR Jl1PERIALISM ? . 56 CONCLUSIONS •• . 81 APPENDIX . • • . 93 BIBLIOOMPHY . .. 95 if t CR<\.PTER I The Historical Background In order properly to understand present Israeli assistance to the newly-independent African states, it is necessary to trace the his torical development of the Jewish and African nations and to sketch some of the major problems encountered by each. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 3 October 2001 English Original: English/French

United Nations A/56/428 General Assembly Distr.: General 3 October 2001 English Original: English/French Fifty-sixth session Agenda item 88 Report of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories Report of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories Note by the Secretary-General* The General Assembly, at its fifty-fifth session, adopted resolution 55/130 on the work of the Special Committee to Investigate Israeli Practices Affecting the Human Rights of the Palestinian People and Other Arabs of the Occupied Territories, in which, among other matters, it requested the Special Committee: (a) Pending complete termination of the Israeli occupation, to continue to investigate Israeli policies and practices in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem, and other Arab territories occupied by Israel since 1967, especially Israeli lack of compliance with the provisions of the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, of 12 August 1949, and to consult, as appropriate, with the International Committee of the Red Cross according to its regulations in order to ensure that the welfare and human rights of the peoples of the occupied territories are safeguarded and to report to the Secretary- General as soon as possible and whenever the need arises thereafter; (b) To submit regularly to the Secretary-General periodic reports on the current situation in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem; (c) To continue to investigate the treatment of prisoners in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem, and other Arab territories occupied by Israel since 1967. -

Greater Jerusalem” Has Jerusalem (Including the 1967 Rehavia Occupied and Annexed East Jerusalem) As Its Centre

4 B?63 B?466 ! np ! 4 B?43 m D"D" np Migron Beituniya B?457 Modi'in Bei!r Im'in Beit Sira IsraelRei'ut-proclaimed “GKharbrathae al Miasbah ter JerusaBeitl 'Uer al Famuqa ” D" Kochav Ya'akov West 'Ein as Sultan Mitzpe Danny Maccabim D" Kochav Ya'akov np Ma'ale Mikhmas A System of Settler-Colonialism and Apartheid Deir Quruntul Kochav Ya'akov East ! Kafr 'Aqab Kh. Bwerah Mikhmas ! Beit Horon Duyuk at Tahta B?443 'Ein ad D" Rafat Jericho 'Ajanjul ya At Tira np ya ! Beit Liq Qalandi Kochav Ya'akov South ! Lebanon Neve Erez ¥ ! Qalandiya Giv'at Ze'ev D" a i r Jaba' y 60 Beit Duqqu Al Judeira 60 B? a S Beit Nuba D" B? e Atarot Ind. Zone S Ar Ram Ma'ale Hagit Bir Nabala Geva Binyamin n Al Jib a Beit Nuba Beit 'Anan e ! Giv'on Hahadasha n a r Mevo Horon r Beit Ijza e t B?4 i 3 Dahiyat al Bareed np 6 Jaber d Aqbat e Neve Ya'akov 4 M Yalu B?2 Nitaf 4 !< ! ! Kharayib Umm al Lahim Qatanna Hizma Al Qubeiba ! An Nabi Samwil Ein Prat Biddu el Almon Har Shmu !< Beit Hanina al Balad Kfar Adummim ! Beit Hanina D" 436 Vered Jericho Nataf B? 20 B? gat Ze'ev D" Dayr! Ayyub Pis A 4 1 Tra Beit Surik B?37 !< in Beit Tuul dar ! Har A JLR Beit Iksa Mizpe Jericho !< kfar Adummim !< 21 Ma'ale HaHamisha B? 'Anata !< !< Jordan Shu'fat !< !< A1 Train Ramat Shlomo np Ramot Allon D" Shu'fat !< !< Neve Ilan E1 !< Egypt Abu Ghosh !< B?1 French Hill Mishor Adumim ! B?1 Beit Naqquba !< !< !< ! Beit Nekofa Mevaseret Zion Ramat Eshkol 1 Israeli Police HQ Mesilat Zion B? Al 'Isawiya Lifta a Qulunyia ! Ma'alot Dafna Sho'eva ! !< Motza Sheikh Jarrah !< Motza Illit Mishor Adummim Ind. -

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights

A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights © Copyright 2010, The Veritas Handbook. 1st Edition: July 2010. Online PDF, Cost: $0.00 Cover Photo: Ahmad Mesleh This document may be reproduced and redistributed, in part, or in full, for educational and non- profit purposes only and cannot be used for fundraising or any monetary purposes. We encourage you to distribute the material and print it, while keeping the environment in mind. Photos by Ahmad Mesleh, Jon Elmer, and Zoriah are copyrighted by the authors and used with permission. Please see www.jonelmer.ca, www.ahmadmesleh.wordpress.com and www.zoriah.com for detailed copyright information and more information on these photographers. Excerpts from Rashid Khalidi’s Palestinian Identity, Ben White’s Israeli Apartheid: A Beginner’s Guide and Norman Finkelstein’s This Time We Went Too Far are also taken with permission of the author and/or publishers and can only be used for the purposes of this handbook. Articles from The Electronic Intifada and PULSE Media have been used with written permission. We claim no rights to the images included or content that has been cited from other online resources. Contact: [email protected] Web: www.veritashandbook.blogspot.com T h e V E R I T A S H a n d b o o k 2 A Guide to Understanding the Struggle for Palestinian Human Rights To make this handbook possible, we would like to thank 1. The Hasbara Handbook and the Hasbara Fellowships 2. The Israel Project’s Global Language Dictionary Both of which served as great inspirations, convincing us of the necessity of this handbook in our plight to establish truth and justice. -

1948 Arab‒Israeli

1948 Arab–Israeli War 1 1948 Arab–Israeli War מלחמת or מלחמת העצמאות :The 1948 Arab–Israeli War, known to Israelis as the War of Independence (Hebrew ,מלחמת השחרור :, Milkhemet Ha'atzma'ut or Milkhemet HA'sikhror) or War of Liberation (Hebrewהשחרור Milkhemet Hashikhrur) – was the first in a series of wars fought between the State of Israel and its Arab neighbours in the continuing Arab-Israeli conflict. The war commenced upon the termination of the British Mandate of Palestine and the Israeli declaration of independence on 15 May 1948, following a period of civil war in 1947–1948. The fighting took place mostly on the former territory of the British Mandate and for a short time also in the Sinai Peninsula and southern Lebanon.[1] ., al-Nakba) occurred amidst this warﺍﻟﻨﻜﺒﺔ :Much of what Arabs refer to as The Catastrophe (Arabic The war concluded with the 1949 Armistice Agreements. Background Following World War II, on May 14, 1948, the British Mandate of Palestine came to an end. The surrounding Arab nations were also emerging from colonial rule. Transjordan, under the Hashemite ruler Abdullah I, gained independence from Britain in 1946 and was called Jordan, but it remained under heavy British influence. Egypt, while nominally independent, signed the Anglo-Egyptian Treaty of 1936 that included provisions by which Britain would maintain a garrison of troops on the Suez Canal. From 1945 on, Egypt attempted to renegotiate the terms of this treaty, which was viewed as a humiliating vestige of colonialism. Lebanon became an independent state in 1943, but French troops would not withdraw until 1946, the same year that Syria won its independence from France.