The Mixed Member Proportional Representation System and Minority Representation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C

Formulating a Regulatory Stance: The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C. Liber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Health Services Organizations and Policy) in The University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Scott Greer, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Holly Jarman, Co-Chair Professor Daniel Béland, McGill University Professor Paula Lantz Alex C. Liber [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7863-3906 © Alex C. Liber 2020 Dedication For Lindsey and Sophia. I love you both to the ends of the earth and am eternally grateful for your tolerance of this project. ii Acknowledgments To my family – Lindsey, you made the greatest sacrifices that allowed this project to come to fruition. You moved away from your family to Michigan. You allowed me to conduct two months of fieldwork when you were pregnant with our daughter. You helped drafts come together and were a constant sounding board and confidant throughout the long process of writing. This would not have been possible without you. Sophia, Poe, and Jo served as motivation for this project and a distraction from it when each was necessary. Mom, Dad, Chad, Max, Julian, and Olivia, as well as Papa Ernie and Grandma Audrey all, helped build the road that I was able to safely walk down in the pursuit of this doctorate. You served as role models, supports, and friends that I could lean on as I grew into my career and adulthood. Lisa, Tony, and Jessica Suarez stepped up to aid Lindsey and me with childcare amid a move, a career transition, and a pandemic. -

Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1328-7478 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship Sarah Miskin Politics and Public Administration Group 24 March 2003 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Martin Lumb and Janet Wilson for their help with the research into party defections in Australia and Cathy Madden, Scott Bennett, David Farrell and Ben Miskin for reading and commenting on early drafts. -

Stakeholder Engagement Strategies for Designating New Zealand Marine Reserves

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Stakeholder engagement strategies for designating New Zealand marine reserves: A case study of the designation of the Auckland Islands (Motu Maha) Marine Reserve and marine reserves designated under the Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Management Act 2005 Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Development Studies at Victoria University of Wellington By James Mize Victoria University of Wellington 2007 "The use of sea and air is common to all; neither can a title to the ocean belong to any people or private persons, forasmuch as neither nature nor public use and custom permit any possession thereof." -Elizabeth I of England (1533-1603) "It is a curious situation that the sea, from which life first arose should now be threatened by the activities of one form of that life. But the sea, though changed in a sinister way, will continue to exist; the threat is rather to life itself." - Rachel Carson , (1907-1964) The Sea Around Us , 1951 ii Abstract In recent years, marine reserves (areas of the sea where no fishing is allowed) have enjoyed increased popularity with scientists and agencies charged with management of ocean and coastal resources. Much scientific literature documents the ecological and biological rationale for marine reserves, but scholars note the most important consideration for successful establishment reserves is adequate involvement of the relevant stakeholders in their designation. Current guidance for proponents of marine reserves suggests that to be successful, reserves should be designated using “bottom-up” processes favouring cooperative management by resource-dependent stakeholders, as opposed to “top-down” approaches led by management agencies and international conservation organizations. -

Thepretty T Girlsm Agazine

The Pretty T Girls Magazine A publication of the Pretty T Girls Yahoo Group Published for the Most Beautiful Girls In The World September 2017 1 2 In This Issue PAGE Editorial By: Barbara Jean 3 New Transition for NAFB Airman 5 Transgender Deacon Appointed by United Methodist Church 8 The Best Drugstore Makeup Under $5 11 How To Look Modern While Wearing the Retro Makeup Trend 14 How To Prevent Eye Makeup From Running 17 Color Correcting Chart 18 How To Clean Makeup Brushes 18 Bluestocking Blue 19 The Adventures of Judy Sometimes 22 Módhnóirí 23 Tasi’s Musings 25 Humor 31 Angels In The Centerfold 32 Mellissa’s Tips 36 7 Ways To Protect Your Shoes in the Rain 42 Diana Sikes 43 Tasi’s Fashion News 45 Lucille Sorella How to Walk In High Heels 49 Lucille Sorella How to Deal With Envy & Comparison 52 For Wives and S.O.’s of Transsexuals 54 Crossdresser or Fetish Dresser 62 From The Kitchen 66 10 Simple Hacks For Better Outdoor Dining 70 The Gossip Fence 74 Shop Till You Drop 86 Calendar 99 3 Can You Serve? An Editorial by: Barbara Jean Well once again President Trump has stabbed the LGBT community in the back. As we know he wants to ban transgender people from being able to serve in the military. A shock, yes, but with this president nothing is asurprise. Now the big question is can he do it? Defense Secretary Mattis was caught off guard and appalled by the presidents tweet. Admiral Mullen’s the former joint chief of staff called on congress to resist dictating policy on how to treat transgender troops to the pentagon. -

The 2008 Election: Reviewing Seat Allocations Without the Māori Electorate Seats June 2010

working paper The 2008 Election: Reviewing seat allocations without the Māori electorate seats June 2010 Sustainable Future Institute Working Paper 2010/04 Authors Wendy McGuinness and Nicola Bradshaw Prepared by The Sustainable Future Institute, as part of Project 2058 Working paper to support Report 8, Effective M āori Representation in Parliament : Working towards a National Sustainable Development Strategy Disclaimer The Sustainable Future Institute has used reasonable care in collecting and presenting the information provided in this publication. However, the Institute makes no representation or endorsement that this resource will be relevant or appropriate for its readers’ purposes and does not guarantee the accuracy of the information at any particular time for any particular purpose. The Institute is not liable for any adverse consequences, whether they be direct or indirect, arising from reliance on the content of this publication. Where this publication contains links to any website or other source, such links are provided solely for information purposes and the Institute is not liable for the content of such website or other source. Published Copyright © Sustainable Future Institute Limited, June 2010 ISBN 978-1-877473-56-2 (PDF) About the Authors Wendy McGuinness is the founder and chief executive of the Sustainable Future Institute. Originally from the King Country, Wendy completed her secondary schooling at Hamilton Girls’ High School and Edgewater College. She then went on to study at Manukau Technical Institute (gaining an NZCC), Auckland University (BCom) and Otago University (MBA), as well as completing additional environmental papers at Massey University. As a Fellow Chartered Accountant (FCA) specialising in risk management, Wendy has worked in both the public and private sectors. -

Strategic Behavior in Exhaustive Ballot Voting: What Can We Learn from the Fifa World Cup 2018 and 2022 Host Elections?

Daniel Karabekyan STRATEGIC BEHAVIOR IN EXHAUSTIVE BALLOT VOTING: WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE FIFA WORLD CUP 2018 AND 2022 HOST ELECTIONS? BASIC RESEARCH PROGRAM WORKING PAPERS SERIES: ECONOMICS WP BRP 130/EC/2016 This Working Paper is an output of a research project implemented at the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE). Any opinions or claims contained in this Working Paper do not necessarily reflect the views of HSE SERIES: ECONOMICS Daniel Karabekyan2 STRATEGIC BEHAVIOR IN EXHAUSTIVE BALLOT VOTING: WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM THE FIFA WORLD CUP 2018 AND 2022 HOST ELECTIONS?*3 There are many allegations about whether FIFA world cup host countries were chosen honestly or not. We analyse the results of the FIFA Executive Committee voting and reconstruct the set of possible voting situations compatible with the results of each stage. In both elections, we identify strategic behaviour and then analyse the results for honest voting under all compatible voting situations. For the 2018 FIFA world cup election Russia is chosen for all profiles. For the 2022 elections the result depends on the preferences of the FIFA president Sepp Blatter who served as a tie-breaker. If Sepp Blatter prefers Qatar over South Korea and Japan, then Qatar would have been chosen for all profiles. Otherwise there are the possibility that South Korea or Japan would have been chosen as the 2022 host country. Another fact is that if we consider possible vote buying, then it is shown, that the bribery of at least 2 committee members would have been required to guarantee winning of Russia bid and at least 1 member for Qatar. -

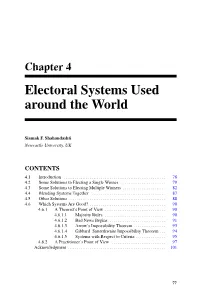

Electoral Systems Used Around the World

Chapter 4 Electoral Systems Used around the World Siamak F. Shahandashti Newcastle University, UK CONTENTS 4.1 Introduction ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 78 4.2 Some Solutions to Electing a Single Winner :::::::::::::::::::::::: 79 4.3 Some Solutions to Electing Multiple Winners ::::::::::::::::::::::: 82 4.4 Blending Systems Together :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 87 4.5 Other Solutions :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 88 4.6 Which Systems Are Good? ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1 A Theorist’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.1 Majority Rules ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 90 4.6.1.2 Bad News Begins :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 91 4.6.1.3 Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem ::::::::::::::::: 93 4.6.1.4 Gibbard–Satterthwaite Impossibility Theorem ::: 94 4.6.1.5 Systems with Respect to Criteria :::::::::::::::: 95 4.6.2 A Practitioner’s Point of View ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 97 Acknowledgment ::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: 101 77 78 Real-World Electronic Voting: Design, Analysis and Deployment 4.1 Introduction An electoral system, or simply a voting method, defines the rules by which the choices or preferences of voters are collected, tallied, aggregated and collectively interpreted to obtain the results of an election [249, 489]. There are many electoral systems. A voter may be allowed to vote for one or multiple candidates, one or multiple predefined lists of candidates, or state their pref- erence among candidates or predefined lists of candidates. Accordingly, tallying may involve a simple count of the number of votes for each candidate or list, or a relatively more complex procedure of multiple rounds of counting and transferring ballots be- tween candidates or lists. Eventually, the outcome of the tallying and aggregation procedures is interpreted to determine which candidate wins which seat. Designing end-to-end verifiable e-voting schemes is challenging. -

Milestones in NZ Sexual Health Compiled by Margaret Sparrow

MILESTONES IN NEW ZEALAND SEXUAL HEALTH by Dr Margaret Sparrow For The Australasian Sexual Health Conference Christchurch, New Zealand, June 2003 To celebrate The 25th Annual General Meeting of the New Zealand Venereological Society And The 25 years since the inaugural meeting of the Society in Wellington on 4 December 1978 And The 15th anniversary of the incorporation of the Australasian College of Sexual Health Physicians on 23 February 1988 TABLE OF CONTENTS Pg Acknowledgments 3 Foreword 4 Glossary of abbreviations 5 Chapter 1 Chronological Synopsis of World Events 7 Chapter 2 New Zealand: Milestones from 1914 to the Present 11 Chapter 3 Dr Bill Platts MBE (1909-2001) 25 Chapter 4 The New Zealand Venereological Society 28 Chapter 5 The Australasian College 45 Chapter 6 International Links 53 Chapter 7 Health Education and Health Promotion 57 Chapter 8 AIDS: Milestones Reflected in the Media 63 Postscript 69 References 70 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Dr Ross Philpot has always been a role model in demonstrating through his own publications the importance of historical records. Dr Janet Say was as knowledgeable, helpful and encouraging as ever. I drew especially on her international experience to help with the chapter on our international links. Dr Heather Lyttle, now in Perth, greatly enhanced the chapter on Dr Bill Platts with her personal reminiscences. Dr Gordon Scrimgeour read the chapter on the NZVS and remembered some things I had forgotten. I am grateful to John Boyd who some years ago found a copy of “The Shadow over New Zealand” in a second hand bookstore in Wellington. Dr Craig Young kindly read the first three chapters and made useful suggestions. -

Amendment Bill

Crimes (Provocation Repeal) Amendment Bill Government Bill As reported from the Justice and Electoral Committee Commentary Recommendation The Justice and Electoral Committee has examined the Crimes (Provocation Repeal) Amendment Bill and recommends that it be passed with the amendments shown. Introduction This bill as introduced proposes to abolish the partial defence of provocation, by repealing sections 169 and 170 of the Crimes Act 1961. Section 169 of the Crimes Act provides that culpable homicide that would otherwise be murder may be reduced to manslaughter if the person who caused the death did so under provocation as defined by the section; section 170 provides that an illegal arrest does not necessarily reduce the offence of murder to manslaughter, but if the offender knows of the illegality then it may be evidence of provoca- tion. 64—2 Crimes (Provocation Repeal) 2 Amendment Bill Commentary Partial defence of provocation abolished We note that the codification of the partial defence of provocation was a reflection of the existing common law partial defence. For the avoidance of doubt, we recommend inserting new clause 5 to make it clear that the common law partial defence would also be abolished by the bill. This would avoid the possibility of defence counsel relying on the defence, so far as it has any effect as a principle of the common law of New Zealand, in cases of culpable homicide. Issues raised in submissions Although we do not recommend amendments as a result of submis- sions we received on the bill, we considered it would be useful to discuss some of the issues that were raised. -

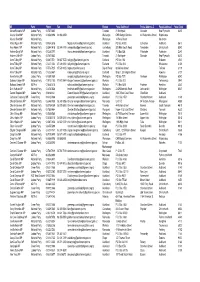

Members Offices As at 21 June 2016.Xlsx

MP Party Phone Fax Email Region Postal Address 1 Postal Address 2 Postal Address 3 Postal Code Adrian Rurawhe MP Labour Party 06 757 5662 Taranaki 21 Northgate Strandon New Plymouth 4312 Alastair Scott MP National Party 06 858 8196 06 858 8459 Wairarapa CHB Budget Services 43 Ruataniwha Street Waipukurau Alastair Scott MP National Party Wairarapa 14 Perry Street Masterton Alfred Ngaro MP National Party 09 834 3676 [email protected] Auckland PO Box 83200 Edmonton Auckland 0610 Amy Adams MP National Party 03 344 0418 03 344 0419 [email protected] Canterbury 829 Main South Road Templeton Christchurch 8042 Andrew Bayly MP National Party 09 238 5977 [email protected] Auckland P O Box 528 Pukekohe Pukekohe 2340 Andrew Little MP Labour Party 06 757 5662 Taranaki 21 Northgate Strandon New Plymouth 4312 Anne Tolley MP National Party 06 867 7571 06 867 7572 [email protected] Eastland PO Box 106 Gisborne 4040 Anne Tolley MP National Party 07 307 1254 07 308 0351 [email protected] Eastland P.O. Box 216 Whakatane 3158 Anne Tolley MP National Party 07 573 7125 07 573 9125 [email protected] Bay of Plenty 68 Jellicoe Street Te Puke 3119 Anne Tolley MP National Party 07 323 6487 [email protected] Eastland Shop 1, 35 Islington Street Kawerau 3127 Annette King MP Labour Party 04 389 0989 [email protected] Wellington PO Box 7071 Newtown Wellington 6242 Barbara Kuriger MP National Party 07 870 1005 07 870 3904 [email protected] Waikato P.O. -

House of Representatives List of Members

FORTY-EIGHTH PARLIAMENT OF NEW ZEALAND ___________ HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ____________ LIST OF MEMBERS 1 September 2008 MEMBERS OF PARLIAMENT Member Electorate/List Party Postal Address and E-mail Address Phone and Fax Anderton, Hon Jim Freepost Parliament, (04) 470 6550 Leader, Progressive Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 495 8441 Minister of Agriculture Wellington 6160 Minister for Biosecurity Minister of Fisheries Wigram Progressive [email protected] Minister of Forestry Minister responsible for the 296 Selwyn St, Spreydon, Christchurch (03) 365 5459 Public Trust PO Box 33 164, Barrington, Christchurch Fax (03) 365 6173 Associate Minister of Health [email protected] Associate Minister for Tertiary Education Freepost Parliament (04) 471 9357 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 437 6447 Ardern MP, Shane Taranaki – King Country National Wellington 6160 [email protected] Freepost Parliament (04) 470 6936 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) 439 6445 Auchinvole, Chris List National Wellington 6160 [email protected] (04) 470 6572 Barker, Hon Rick Freepost Parliament Fax (04) 472 8036 Minister of Internal Affairs Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Minister of Civil Defence Wellington 6160 Minister for Courts List Labour [email protected] Minister of Veterans’ Affairs Associate Minister of Justice PO Box 1245, Hastings (06) 876 8966 Fax (06) 876 4908 Freepost Parliament (04) 471 9906 Private Bag 18 888, Parliament Buildings Fax (04) -

New Zealand Hansard Precedent Manual

IND 1 NEW ZEALAND HANSARD PRECEDENT MANUAL Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 2 ABOUT THIS MANUAL The Precedent Manual shows how procedural events in the House appear in the Hansard report. It does not include events in Committee of the whole House on bills; they are covered by the Committee Manual. This manual is concerned with structure and layout rather than text - see the Style File for information on that. NB: The ways in which the House chooses to deal with procedural matters are many and varied. The Precedent Manual might not contain an exact illustration of what you are looking for; you might have to scan several examples and take parts from each of them. The wording within examples may not always apply. The contents of each section and, if applicable, its subsections, are included in CONTENTS at the front of the manual. At the front of each section the CONTENTS lists the examples in that section. Most sections also include box(es) containing background information; these boxes are situated at the front of the section and/or at the front of subsections. The examples appear in a column format. The left-hand column is an illustration of how the event should appear in Hansard; the right-hand column contains a description of it, and further explanation if necessary. At the end is an index. Precedent Manual: Index 16 July 2004 IND 3 INDEX Absence of Minister see Minister not present Amendment/s to motion Abstention/s ..........................................................VOT3-4 Address in reply ....................................................OP12 Acting Minister answers question.........................