The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

Core 1..186 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 141 Ï NUMBER 051 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, September 22, 2006 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 3121 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, September 22, 2006 The House met at 11 a.m. Foreign Affairs, the actions of the minority Conservative govern- ment are causing the Canadian business community to miss the boat when it comes to trade and investment in China. Prayers The Canadian Chamber of Commerce is calling on the Conservative minority government to bolster Canadian trade and investment in China and encourage Chinese companies to invest in STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS Canada. Business leaders are not alone in their desire for a stronger Ï (1100) economic relationship with China. The Asia-Pacific Foundation [English] released an opinion poll last week where Canadians named China, not the United States, as the most important potential export market CANADIAN FORCES for Canada. Mr. Pierre Lemieux (Glengarry—Prescott—Russell, CPC): Mr. Speaker, I recently met with a special family in my riding. The The Conservatives' actions are being noticed by the Chinese Spence family has a long, proud tradition of military service going government, which recently shut down negotiations to grant Canada back several generations. The father, Rick Spence, is a 27 year approved destination status, effectively killing a multi-million dollar veteran who serves in our Canadian air force. opportunity to allow Chinese tourists to visit Canada. His son, Private Michael Spence, is a member of the 1st Battalion China's ambassador has felt the need to say that we need mutual of the Royal Canadian Regiment. -

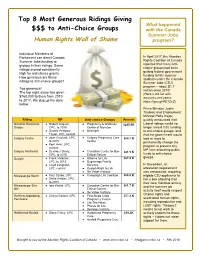

Top 8 Most Generous Ridings Giving $$$ to Anti-Choice Groups

Top 8 Most Generous Ridings Giving What happened $$$ to Anti-Choice Groups with the Canada Summer Jobs Human Rights Wall of Shame program? Individual Members of Parliament can direct Canada In April 2017, the Abortion Summer Jobs funding to Rights Coalition of Canada groups in their ridings. Some reported that many anti- ridings scored consistently choice groups had been getting federal government high for anti-choice grants. funding to hire summer How generous are these students under the Canada ridings to anti-choice groups? Summer Jobs (CSJ) program – about $1.7 Too generous! million since 2010! The top eight alone has given (Here’s the list with $760,000 to them from 2010 amounts and years: to 2017. We dug up the data https://goo.gl/4C1ZsC) below. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Employment Minister Patty Hajdu Riding MP Anti-choice Groups Amount quickly announced that Moncton-Riverview- ● Robert Goguen, ● Pregnancy & Wellness $285.6K Liberal ridings would no Dieppe CPC, to 2015 Centre of Moncton longer award CSJ funding ● Ginette Petitpas- ● Birthright to anti-choice groups, and Taylor, LPC, current that the government would Calgary Centre ● Joan Crockatt, CPC, ● Calgary Pregnancy Care $84.7 K look at ways to to 2015 Centre permanently change the ● Kent Hehr, LPC, program to prevent any current MP from allocating public Calgary Northeast ● Devinder Shory, ● Canadian Centre for Bio- $81.5 K CPC, to 2015 Ethical Reform funds to anti-choice groups. Guelph ● Frank Valeriote, ● Alliance for Life $67.9 K LPC, to 2015 ● Beginnings Family -

The Incorporation of Human Cremation Ashes Into Objects and Tattoos in Contemporary British Practices

Ashes to Art, Dust to Diamonds: The incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos in contemporary British practices Samantha McCormick A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Department of Sociology August 2015 Declaration I declare that the work in this thesis was carried out in accordance with the requirements of the University’s regulations and Code of Practice for Research Degree Programmes and all the material provided in this thesis are original and have not been published elsewhere. I declare that while registered as a candidate for the University’s research degree, I have not been a registered candidate or enrolled student for another award of the University or other academic or professional institution. A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Manchester Metropolitan University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy SINGED ………………………………… i ii Abstract This thesis examines the incorporation of human cremated remains into objects and tattoos in a range of contemporary practices in British society. Referred to collectively in this study as ‘ashes creations’, the practices explored in this research include human cremation ashes irreversibly incorporated or transformed into: jewellery, glassware, diamonds, paintings, tattoos, vinyl records, photograph frames, pottery, and mosaics. This research critically analyses the commissioning, production, and the lived experience of the incorporation of human cremation ashes into objects and tattoos from the perspective of two groups of people who participate in these practices: people who have commissioned an ashes creations incorporating the cremation ashes of a loved one and people who make or sell ashes creations. -

Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship

INFORMATION, ANALYSIS AND ADVICE FOR THE PARLIAMENT INFORMATION AND RESEARCH SERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship DEPARTMENT OF THE PARLIAMENTARY LIBRARY ISSN 1328-7478 Copyright Commonwealth of Australia 2003 Except to the extent of the uses permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means including information storage and retrieval systems, without the prior written consent of the Department of the Parliamentary Library, other than by Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament in the course of their official duties. This paper has been prepared for general distribution to Senators and Members of the Australian Parliament. While great care is taken to ensure that the paper is accurate and balanced, the paper is written using information publicly available at the time of production. The views expressed are those of the author and should not be attributed to the Information and Research Services (IRS). Advice on legislation or legal policy issues contained in this paper is provided for use in parliamentary debate and for related parliamentary purposes. This paper is not professional legal opinion. Readers are reminded that the paper is not an official parliamentary or Australian government document. IRS staff are available to discuss the paper's contents with Senators and Members and their staff but not with members of the public. Published by the Department of the Parliamentary Library, 2003 I NFORMATION AND R ESEARCH S ERVICES Research Paper No. 4 2002–03 Politician Overboard: Jumping the Party Ship Sarah Miskin Politics and Public Administration Group 24 March 2003 Acknowledgments I would like to thank Martin Lumb and Janet Wilson for their help with the research into party defections in Australia and Cathy Madden, Scott Bennett, David Farrell and Ben Miskin for reading and commenting on early drafts. -

Proactive Release

Proactive Release Date: 5 August 2019 The following Cabinet paper and related Cabinet minutes have been proactively released by the Minister of Foreign Affairs: First Voluntary National Review on New Zealand’s Progress Towards the Sustainable Development Goals: (CAB-19-MIN-223) He Waka Eke Noa Towards a Better Future, Together – New Zealand’s Progress Towards the SDGs 2019 – Draft Report: (GOV-19-MIN-024 refers) He Waka Eke Noa Towards a Better Future, Together – New Zealand’s Progress Towards the SDGs 2019 – Design templates Please note the delays in releasing these papers were owing to agency processes to finalise the documents for release. © Crown Copyright, Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) CAB-19-MIN-0223 Cabinet Minute of Decision This document contains information for the New Zealand Cabinet. It must be treated in confidence and handled in accordance with any security classification, or other endorsement. The information can only be released, including under the Official Information Act 1982, by persons with the appropriate authority. Report of the Cabinet Government Administration and Expenditure Review Committee: Period Ended 10 May 2019 Affairs On 13 May 2019, Cabinet made the following decisions on the work of the Cabinet Government Administration and Expenditure Review Committee for the period ended 10 May 2019: GOV-19-MIN-0024 First Voluntary National Review on New Zealand’s CONFIRMED Progress Toward the Sustainable Development GoalsForeign Portfolio: Foreign Affairs of Out of scope Minister the by -

Stakeholder Engagement Strategies for Designating New Zealand Marine Reserves

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Stakeholder engagement strategies for designating New Zealand marine reserves: A case study of the designation of the Auckland Islands (Motu Maha) Marine Reserve and marine reserves designated under the Fiordland (Te Moana o Atawhenua) Marine Management Act 2005 Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Development Studies at Victoria University of Wellington By James Mize Victoria University of Wellington 2007 "The use of sea and air is common to all; neither can a title to the ocean belong to any people or private persons, forasmuch as neither nature nor public use and custom permit any possession thereof." -Elizabeth I of England (1533-1603) "It is a curious situation that the sea, from which life first arose should now be threatened by the activities of one form of that life. But the sea, though changed in a sinister way, will continue to exist; the threat is rather to life itself." - Rachel Carson , (1907-1964) The Sea Around Us , 1951 ii Abstract In recent years, marine reserves (areas of the sea where no fishing is allowed) have enjoyed increased popularity with scientists and agencies charged with management of ocean and coastal resources. Much scientific literature documents the ecological and biological rationale for marine reserves, but scholars note the most important consideration for successful establishment reserves is adequate involvement of the relevant stakeholders in their designation. Current guidance for proponents of marine reserves suggests that to be successful, reserves should be designated using “bottom-up” processes favouring cooperative management by resource-dependent stakeholders, as opposed to “top-down” approaches led by management agencies and international conservation organizations. -

30 March 2012 Page 1 of 17

Radio 4 Listings for 24 – 30 March 2012 Page 1 of 17 SATURDAY 24 MARCH 2012 SAT 06:57 Weather (b01dc94s) The Scotland Bill is currently progressing through the House of The latest weather forecast. Lords, but is it going to stop independence in its tracks? Lord SAT 00:00 Midnight News (b01dc948) Forsyth Conservative says it's unlikely Liberal Democrat Lord The latest national and international news from BBC Radio 4. Steel thinks it will. Followed by Weather. SAT 07:00 Today (b01dtd56) With John Humphrys and James Naughtie. Including Yesterday The Editor is Marie Jessel in Parliament, Sports Desk, Weather and Thought for the Day. SAT 00:30 Book of the Week (b01dnn41) Tim Winton: Land's Edge - A Coastal Memoir SAT 11:30 From Our Own Correspondent (b01dtd5j) SAT 09:00 Saturday Live (b01dtd58) Afghans enjoy New Year celebrations but Lyse Doucet finds Episode 5 Mark Miodownik, Luke Wright, literacy champion Sue they are concerned about what the months ahead may bring Chapman, saved by a Labradoodle, Chas Hodges Daytrip, Sarah by Tim Winton. Millican John James travels to the west African state of Guinea-Bissau and finds unexpected charms amidst its shadows In a specially-commissioned coda, the acclaimed author Richard Coles with materials scientist Professor Mark describes how the increasingly threatened and fragile marine Miodownik, poet Luke Wright, Sue Chapman who learned to The Burmese are finding out that recent reforms in their ecology has turned him into an environmental campaigner in read and write in her sixties, Maurice Holder whose life was country have encouraged tourists to return. -

Debates of the Senate

Debates of the Senate 1st SESSION . 42nd PARLIAMENT . VOLUME 150 . NUMBER 52 OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, June 17, 2016 The Honourable GEORGE J. FUREY Speaker CONTENTS (Daily index of proceedings appears at back of this issue). Debates Services: D'Arcy McPherson, National Press Building, Room 906, Tel. 613-995-5756 Publications Centre: Kim Laughren, National Press Building, Room 926, Tel. 613-947-0609 Published by the Senate Available on the Internet: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1207 THE SENATE Friday, June 17, 2016 The Senate met at 9 a.m., the Speaker in the chair. quarantine of Iranian society so that they may more firmly hold it in their grip. Prayers. Honourable senators, newspaper reports suggest that our federal government is ``actively engaged'' in this case and SENATORS' STATEMENTS working closely with allies to assist Homa Hoodfar. It is my hope that their efforts to free both Saeed Malekpour and Homa Hoodfar from the malign and criminal Iranian regime IRAN will be successful. DETENTION OF HOMA HOODFAR In the meantime, I know that all honourable senators will continue to follow their cases with deep concern as we continue to Hon. Linda Frum: Honourable senators, as I rise today, I note condemn the brutal regime that has seen fit to take them hostage. that it has been almost exactly one month to this day since the Senate of Canada conducted its inquiry into the plight of innocently detained political prisoners in Iran. Today, I wish to remind us all that holding Iran accountable for PAUL G. KITCHEN its flagrant abuses of human rights cannot solely take place during a two-day inquiry, or even an annual Iran Accountability Week; it ROTHESAY NETHERWOOD SCHOOL— must take place every single day, because, sadly, there is great CONGRATULATIONS ON RETIREMENT cause for vigilance on this matter. -

SFU Thesis Template Files

The Right to Authentic Political Communication by Ann Elizabeth Rees M.A., Simon Fraser University, 2005 B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1980 Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the School of Communication Faculty of Arts and Social Science Ann Elizabeth Rees 2016 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Spring 2016 Approval Name: Ann Elizabeth Rees Degree: Doctor of Philosophy Title: The Right to Authentic Political Communication Examining Committee: Chair: Katherine Reilly, Assistant Professor Peter Anderson Senior Supervisor Associate Professor Catherine Murray Supervisor Professor Alison Beale Supervisor Professor Andrew Heard Internal Examiner Associate Professor Political Science Department Paul Thomas External Examiner Professor Emeritus Department of Political Studies University of Manitoba Date Defended/Approved: January 22, 2016 ii Abstract Increasingly, governments communicate strategically with the public for political advantage, seeking as Christopher Hood describes it to “avoid blame” and “claim credit” for the actions and decisions of governance. In particular, Strategic Political Communication (SPC) is becoming the dominant form of political communication between Canada’s executive branch of government and the public, both during elections and as part of a “permanent campaign” to gain and maintain public support as means to political power. This dissertation argues that SPC techniques interfere with the public’s ability to know how they are governed, and therefore undermines the central right of citizens in a democracy to legitimate elected representation by scrutinizing government and holding it to account. Realization of that right depends on an authentic political communication process that provides citizens with an understanding of government. By seeking to hide or downplay blameworthy actions, SPC undermines the legitimation role public discourse plays in a democracy. -

The Subject-Matter of Those Elements Contained in Part 5 of Bill C-74

MAY 2018 THE SUBJECT-MATTER OF THOSE ELEMENTS CONTAINED IN PART 5 OF BILL C-74: AN ACT TO IMPLEMENT CERTAIN PROVISIONS OF THE BUDGET TABLED IN PARLIAMENT ON FEBRUARY 27, 2018 AND OTHER MEASURES Report of the Standing Senate Committee on Energy, the Environment and Natural Resources The Honourable Rosa Galvez, Chair The Honourable Michael L. MacDonald, Deputy Chair For more information please contact us: by email: [email protected] by mail: The Standing Senate Committee on Energy, the Environment and Natural Resources Senate, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada, K1A 0A4 This report can be downloaded at: www.senate-senat.ca/enev The Senate is on Twitter: @SenateCA, follow the committee using the hashtag #ENEV Ce rapport est également offert en français THE SUBJECT-MATTER OF THOSE ELEMENTS CONTAINED IN PART 5 OF BILL C-74 3 TABLE OF CONTENTS THE COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP ................................................................... 5 ORDER OF REFERENCE .............................................................................. 6 INTRODUCTION........................................................................................ 9 THE GREENHOUSE GAS POLLUTION PRICING ACT: DESIGN AND IMPLEMENTATION .................................................................................... 9 GENERAL DISCUSSION FROM WITNESSES ................................................ 12 A. Carbon Pricing as an Economic Instrument ...................................... 12 B. Competitiveness .......................................................................... -

Home for Progressive Politics? an Analysis of Labour's Sucess in New

ANALYSIS • On 17 October 2020, voters in New Zealand re-elected a Labour Government in what DEMOCRACY AND HUMAN RIGHTS has been labelled an historic, landslide victory. The final count was announced on 6 Novem- ber, Labour’s share of the vote had grown to 50 per cent and HOME FOR 65 seats. PROGRESSIVE • In combination with the Green and Māori Party, these results POLITICS? indicate that 59.1 per cent of voters opted for the progressive left, which now holds 64 per An Analysis of Labour’s Success in New Zealand cent of parliamentary seats. Jennifer Curtin • December 2020 This result represents a signif- icant win for the left in New Zealand. It is the largest share of the vote won by the Labour Party in 82 years (50 per cent in 2020, compared to 55 per cent in 1938). The magnitude of Labour’s win cannot be underestimated. DEMOCRACY AND HUMAN RIGHTS HOME FOR PROGRESSIVE POLITICS? An Analysis of Labour’s Success in New Zealand Contents 1 ADVANCING PROGRESSIVE POLITICS THROUGH INCLUSIVE LEADERSHIP 2 2 LABOUR’S RECORD IN OFFICE – INCREMENTALISM OVER TRANSFOR MATION 4 3 THE FUTURE OF PROGRESSIVE POLITICS IN NEW ZEALAND 8 1 FRIEDRICH-EBERT-STIFTUNG – Home for Progressive Politics? On 17 October 2020, voters in New Zealand re-elected a power ful shift in whose voices are represented in parliament Labour Government in what has been labelled an historic, and cabinet, what implications might this have for policy landslide victory. On election night, the Labour Party had change? Second, what progressive policy wins did Labour won 49.1 per cent of the vote, and 64 seats in the 120-seat achieve in its first three years, given their unexpected gains parliament, while the Greens secured 7.6 per cent of the in 2017, and their coalition agreement with a conservative vote and 10 seats.