SFU Thesis Template Files

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Honourable Marc Garneau P.C., M.P. Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Global Affairs Canada 125 Sussex Drive Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0G2

The Honourable Marc Garneau P.C., M.P. Minister of Foreign Affairs of Canada Global Affairs Canada 125 Sussex Drive Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0G2 Tuesday, June 22nd 2021 Object: Audit of the financial and personal connections of Hong Kong officials in Canada Dear Minister, We the undersigned, are writing to raise our concern about the deteriorating human rights situation in Hong Kong and to urge the Canadian Government to undertake an audit of the financial and personal connections Hong Kong officials have in Canada. In the recent months, we have seen Beijing continue its crackdown on the pro-democracy movement in Hong Kong with the mass arrest and charging of 47 pro-democracy activists under the National Security Law, the introduction of electoral reform which would prevent pro- democracy parties from standing for election, the freezing of the owner of Apple Daily Jimmy Lai’s assets, the passing of an Immigration Bill which would give the Chinese Government the power to restrict freedom of movement into and out of the city, and the banning of the June 4 Tiananmen Square vigil. In the middle of Beijing’s destruction of Hong Kong’s autonomy, rule of law, and way of life, stand thousands of Canadian citizens who are fearful of their future in the city. They are desperately waiting on the Canadian Government and its allies to act. With nearly every prominent pro-democracy voice in Hong Kong in jail, awaiting trial, or overseas in exile, it is clear that there is an increased need for a robust and coordinated response against the Hong Kong officials who are responsible for human rights abuses and the crackdown on the pro- democracy movement in the city. -

Core 1..39 Journalweekly (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

HOUSE OF COMMONS OF CANADA CHAMBRE DES COMMUNES DU CANADA 40th PARLIAMENT, 3rd SESSION 40e LÉGISLATURE, 3e SESSION Journals Journaux No. 2 No 2 Thursday, March 4, 2010 Le jeudi 4 mars 2010 10:00 a.m. 10 heures PRAYERS PRIÈRE DAILY ROUTINE OF BUSINESS AFFAIRES COURANTES ORDINAIRES TABLING OF DOCUMENTS DÉPÔT DE DOCUMENTS Pursuant to Standing Order 32(2), Mr. Lukiwski (Parliamentary Conformément à l'article 32(2) du Règlement, M. Lukiwski Secretary to the Leader of the Government in the House of (secrétaire parlementaire du leader du gouvernement à la Chambre Commons) laid upon the Table, — Government responses, des communes) dépose sur le Bureau, — Réponses du pursuant to Standing Order 36(8), to the following petitions: gouvernement, conformément à l’article 36(8) du Règlement, aux pétitions suivantes : — Nos. 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, — nos 402-1109 to 402-1111, 402-1132, 402-1147, 402-1150, 402- 402-1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 1185, 402-1222, 402-1246, 402-1259, 402-1321, 402-1336, 402- 402-1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 and 402-1513 1379, 402-1428, 402-1485, 402-1508 et 402-1513 au sujet du concerning the Employment Insurance Program. — Sessional régime d'assurance-emploi. — Document parlementaire no 8545- Paper No. 8545-403-1-01; 403-1-01; — Nos. 402-1129, 402-1174 and 402-1268 concerning national — nos 402-1129, 402-1174 et 402-1268 au sujet des parcs parks. — Sessional Paper No. 8545-403-2-01; nationaux. — Document parlementaire no 8545-403-2-01; — Nos. -

Dealing with Crisis

Briefing on the New Parliament December 12, 2019 CONFIDENTIAL – FOR INTERNAL USE ONLY Regional Seat 8 6 ON largely Flip from NDP to Distribution static 33 36 Bloc Liberals pushed out 10 32 Minor changes in Battleground B.C. 16 Liberals lose the Maritimes Goodale 1 12 1 1 2 80 10 1 1 79 1 14 11 3 1 5 4 10 17 40 35 29 33 32 15 21 26 17 11 4 8 4 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 2015 2019 BC AB MB/SK ON QC AC Other 2 Seats in the House Other *As of December 5, 2019 3 Challenges & opportunities of minority government 4 Minority Parliament In a minority government, Trudeau and the Liberals face a unique set of challenges • Stable, for now • Campaign driven by consumer issues continues 5 Minority Parliament • Volatile and highly partisan • Scaled back agenda • The budget is key • Regulation instead of legislation • Advocacy more complicated • House committee wild cards • “Weaponized” Private Members’ Bills (PMBs) 6 Kitchen Table Issues and Other Priorities • Taxes • Affordability • Cost of Living • Healthcare Costs • Deficits • Climate Change • Indigenous Issues • Gender Equality 7 National Unity Prairies and the West Québéc 8 Federal Fiscal Outlook • Parliamentary Budget Officer’s most recent forecast has downgraded predicted growth for the economy • The Liberal platform costing projected adding $31.5 billion in new debt over the next four years 9 The Conservatives • Campaigned on cutting regulatory burden, review of “corporate welfare” • Mr. Scheer called a special caucus meeting on December 12 where he announced he was stepping -

Core 1..186 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 10.50)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 141 Ï NUMBER 051 Ï 1st SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, September 22, 2006 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) 3121 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, September 22, 2006 The House met at 11 a.m. Foreign Affairs, the actions of the minority Conservative govern- ment are causing the Canadian business community to miss the boat when it comes to trade and investment in China. Prayers The Canadian Chamber of Commerce is calling on the Conservative minority government to bolster Canadian trade and investment in China and encourage Chinese companies to invest in STATEMENTS BY MEMBERS Canada. Business leaders are not alone in their desire for a stronger Ï (1100) economic relationship with China. The Asia-Pacific Foundation [English] released an opinion poll last week where Canadians named China, not the United States, as the most important potential export market CANADIAN FORCES for Canada. Mr. Pierre Lemieux (Glengarry—Prescott—Russell, CPC): Mr. Speaker, I recently met with a special family in my riding. The The Conservatives' actions are being noticed by the Chinese Spence family has a long, proud tradition of military service going government, which recently shut down negotiations to grant Canada back several generations. The father, Rick Spence, is a 27 year approved destination status, effectively killing a multi-million dollar veteran who serves in our Canadian air force. opportunity to allow Chinese tourists to visit Canada. His son, Private Michael Spence, is a member of the 1st Battalion China's ambassador has felt the need to say that we need mutual of the Royal Canadian Regiment. -

The Honourable Christian Paradis, Canadian Minister of Industry and Minister of State to Ring the NASDAQ Stock Market Closing Bell

The Honourable Christian Paradis, Canadian Minister of Industry and Minister of State to Ring The NASDAQ Stock Market Closing Bell ADVISORY, Nov. 30, 2011 (GLOBE NEWSWIRE) -- What: The Honourable Christian Paradis, Canadian Minister of Industry and Minister of State (Agriculture), will visit the NASDAQ MarketSite in New York City's Times Square to officially ring The NASDAQ Stock Market Closing Bell. Where: NASDAQ MarketSite — 4 Times Square — 43rd & Broadway — Broadcast Studio When: Thursday, December 1st, 2011 — 3:45 p.m. to 4:00 p.m. ET Contact: Richard Walker Director of Communications Office of the Honourable Christian Paradis Minister of Industry (613) 995-9001 NASDAQ MarketSite: Jen Knapp (212) 401-8916 [email protected] Feed Information: Fiber Line (Encompass Waterfront): 4463 Gal 3C/06C 95.05 degrees West 18 mhz Lower DL 3811 Vertical FEC 3/4 SR 13.235 DR 18.295411 MOD 4:2:0 DVBS QPSK Facebook and Twitter: For multimedia features such as exclusive content, photo postings, status updates and video of bell ceremonies please visit our Facebook page at: http://www.facebook.com/nasdaqomx For news tweets, please visit our Twitter page at: http://twitter.com/nasdaqomx Webcast: A live webcast of the NASDAQ Closing Bell will be available at: http://www.nasdaq.com/about/marketsitetowervideo.asx or http://social.nasdaqomx.com. Photos: To obtain a hi-resolution photograph of the Market Close, please go to http://www.nasdaq.com/reference/marketsite_events.stm and click on the market close of your choice. About Christian Paradis: Christian Paradis was named Minister of Industry and Minister of State (Agriculture) on May 18, 2011. -

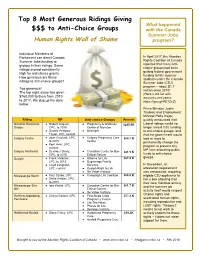

Top 8 Most Generous Ridings Giving $$$ to Anti-Choice Groups

Top 8 Most Generous Ridings Giving What happened $$$ to Anti-Choice Groups with the Canada Summer Jobs Human Rights Wall of Shame program? Individual Members of Parliament can direct Canada In April 2017, the Abortion Summer Jobs funding to Rights Coalition of Canada groups in their ridings. Some reported that many anti- ridings scored consistently choice groups had been getting federal government high for anti-choice grants. funding to hire summer How generous are these students under the Canada ridings to anti-choice groups? Summer Jobs (CSJ) program – about $1.7 Too generous! million since 2010! The top eight alone has given (Here’s the list with $760,000 to them from 2010 amounts and years: to 2017. We dug up the data https://goo.gl/4C1ZsC) below. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and Employment Minister Patty Hajdu Riding MP Anti-choice Groups Amount quickly announced that Moncton-Riverview- ● Robert Goguen, ● Pregnancy & Wellness $285.6K Liberal ridings would no Dieppe CPC, to 2015 Centre of Moncton longer award CSJ funding ● Ginette Petitpas- ● Birthright to anti-choice groups, and Taylor, LPC, current that the government would Calgary Centre ● Joan Crockatt, CPC, ● Calgary Pregnancy Care $84.7 K look at ways to to 2015 Centre permanently change the ● Kent Hehr, LPC, program to prevent any current MP from allocating public Calgary Northeast ● Devinder Shory, ● Canadian Centre for Bio- $81.5 K CPC, to 2015 Ethical Reform funds to anti-choice groups. Guelph ● Frank Valeriote, ● Alliance for Life $67.9 K LPC, to 2015 ● Beginnings Family -

BACKBENCHERS So in Election Here’S to You, Mr

Twitter matters American political satirist Stephen Colbert, host of his and even more SPEAKER smash show The Colbert Report, BACKBENCHERS so in Election Here’s to you, Mr. Milliken. poked fun at Canadian House Speaker Peter politics last week. p. 2 Former NDP MP Wendy Lill Campaign 2011. p. 2 Milliken left the House of is the writer behind CBC Commons with a little Radio’s Backbenchers. more dignity. p. 8 COLBERT Heard on the Hill p. 2 TWITTER TWENTY-SECOND YEAR, NO. 1082 CANADA’S POLITICS AND GOVERNMENT NEWSWEEKLY MONDAY, APRIL 4, 2011 $4.00 Tories running ELECTION CAMPAIGN 2011 Lobbyists ‘pissed’ leaner war room, Prime Minister Stephen Harper on the hustings they can’t work on focused on election campaign, winning majority This campaign’s say it’s against their This election campaign’s war room Charter rights has 75 to 90 staffers, with the vast majority handling logistics of about one man Lobbying Commissioner Karen the Prime Minister’s tour. Shepherd tells lobbyists that working on a political By KRISTEN SHANE and how he’s run campaign advances private The Conservatives are running interests of public office holder. a leaner war room and a national campaign made up mostly of cam- the government By BEA VONGDOUANGCHANH paign veterans, some in new roles, whose goal is to persuade Canadi- Lobbyists are “frustrated” they ans to re-elect a “solid, stable Con- can’t work on the federal elec- servative government” to continue It’s a Harperendum, a tion campaign but vow to speak Canada’s economic recovery or risk out against a regulation that they a coalition government headed by national verdict on this think could be an unconstitutional Liberal Leader Michael Ignatieff. -

The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C

Formulating a Regulatory Stance: The Comparative Politics of E-Cigarette Regulation in Australia, Canada and New Zealand by Alex C. Liber A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Health Services Organizations and Policy) in The University of Michigan 2020 Doctoral Committee: Professor Scott Greer, Co-Chair Assistant Professor Holly Jarman, Co-Chair Professor Daniel Béland, McGill University Professor Paula Lantz Alex C. Liber [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0001-7863-3906 © Alex C. Liber 2020 Dedication For Lindsey and Sophia. I love you both to the ends of the earth and am eternally grateful for your tolerance of this project. ii Acknowledgments To my family – Lindsey, you made the greatest sacrifices that allowed this project to come to fruition. You moved away from your family to Michigan. You allowed me to conduct two months of fieldwork when you were pregnant with our daughter. You helped drafts come together and were a constant sounding board and confidant throughout the long process of writing. This would not have been possible without you. Sophia, Poe, and Jo served as motivation for this project and a distraction from it when each was necessary. Mom, Dad, Chad, Max, Julian, and Olivia, as well as Papa Ernie and Grandma Audrey all, helped build the road that I was able to safely walk down in the pursuit of this doctorate. You served as role models, supports, and friends that I could lean on as I grew into my career and adulthood. Lisa, Tony, and Jessica Suarez stepped up to aid Lindsey and me with childcare amid a move, a career transition, and a pandemic. -

The Victims of Substantive Representation: How "Women's Interests" Influence the Career Paths of Mps in Canada (1997-2011)

The Victims of Substantive Representation: How "Women's Interests" Influence the Career Paths of MPs in Canada (1997-2011) by Susan Piercey A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Arts Department of Political Science Memorial University September, 2011 St. John's Newfoundland Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r&tirence ISBN: 978-0-494-81979-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-81979-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

BANC Issue35 1..104

First Session Première session de la Forty-first Parliament, 2011-12-13 quarante et unième législature, 2011-2012-2013 Proceedings of the Standing Délibérations du Comité Senate Committee on sénatorial permanent des Banking, Trade and Banques et Commerce du commerce Chair: Président : The Honourable IRVING GERSTEIN L'honorable IRVING GERSTEIN Wednesday, May 29, 2013 Le mercredi 29 mai 2013 Thursday, May 30, 2013 Le jeudi 30 mai 2013 Issue No. 35 Fascicule no 35 Third and fourth meetings on: Troisième et quatrième réunions concernant : Bill C-377, An Act to amend Le projet de loi C-377, Loi modifiant la the Income Tax Act Loi de l'impôt sur le revenu (requirements for labour organizations) (exigences applicables aux organisations ouvrières) WITNESSES: TÉMOINS : (See back cover) (Voir à l'endos) 50179-50186 STANDING SENATE COMMITTEE ON COMITÉ SÉNATORIAL PERMANENT DES BANKING, TRADE AND COMMERCE BANQUES ET DU COMMERCE The Honourable Irving Gerstein, Chair Président : L'honorable Irving Gerstein The Honourable Céline Hervieux-Payette, P.C., Deputy Chair Vice-présidente : L'honorable Céline Hervieux-Payette, C.P. and et The Honourable Senators: Les honorables sénateurs : Black Maltais Black Maltais Campbell Massicotte Campbell Massicotte * Cowan Moore * Cowan Moore (or Tardif) Oliver (ou Tardif) Oliver Greene Ringuette Greene Ringuette * LeBreton, P.C. Segal * LeBreton, C.P. Segal (or Carignan) Tkachuk (ou Carignan) Tkachuk * Ex officio members * Membres d'office (Quorum 4) (Quorum 4) Changes in membership of the committee: Modifications de la composition du comité : Pursuant to rule 12-5, membership of the committee was Conformément à l'article 12-5 du Règlement, la liste des membres amended as follows: du comité est modifiée, ainsi qu'il suit : The Honourable Senator Segal replaced the Honourable Senator L'honorable sénateur Segal a remplacé l'honorable sénatrice Nancy Ruth (May 30, 2013). -

Pink Crude Tar Sands Supporters Criticized for Using Gay Rights to Mask Environmental Disaster

Pink Crude: Tar sands supporters criticized for using gay rights to mask... http://www.dominionpaper.ca/articles/4205 ISSUE: 79 SECTION: Canadian News GEOGRAPHY: Canada TOPICS: ethical oil , pink-washing , tar sands OCTOBER 21, 2011 Pink Crude Tar sands supporters criticized for using gay rights to mask environmental disaster by JESSE GRASS The Dominion - http://www.dominionpaper.ca MONTREAL—As the negative environmental and health impacts of the Alberta tar sands grow, defenders of the huge oil extraction project continue to try to green-wash the endeavour by leaning on arguments that make it appear more environmentally friendly than it truly is. Recently, industry backers have added "pink-washing"—brandishing queer rights to promote Alberta's oil as an ethical choice. This past September, former Conservative government aide Alykhan Velshi launched a media blitz to build on right-wing pundit Ezra Levant's push to re-brand the tar sands as “Ethical Oil.” The centrepiece of Velshi's campaign is a series of seven ads, presenting two images each: on the left, a frightening scene from PHOTO: KERRI FLANNIGAN a state in which conflict oil is produced; on the right, a polished image of a happy white DEL.ICIO SHARE Canadian worker or pristine landscape. "While working in Afghanistan I have “[Canadians] have a choice to rarely seen any reports in the mainstream make: Ethical Oil from press that truly reflect the situation here. Canada...and other liberal For journalists keen on spreading the truth, democracies, or Conflict Oil from newspapers like the Dominion are politically oppressive...regimes,” essential. They give us hope." --Chris Sands, explains Velshi in a blog entry on freelance journalist living in Afghanistan The Huffington Post. -

Core 1..192 Hansard (PRISM::Advent3b2 9.00)

CANADA House of Commons Debates VOLUME 142 Ï NUMBER 028 Ï 2nd SESSION Ï 39th PARLIAMENT OFFICIAL REPORT (HANSARD) Friday, November 30, 2007 Speaker: The Honourable Peter Milliken CONTENTS (Table of Contents appears at back of this issue.) Also available on the Parliament of Canada Web Site at the following address: http://www.parl.gc.ca 1569 HOUSE OF COMMONS Friday, November 30, 2007 The House met at 10 a.m. were able to eliminate the national deficit and pay down the national debt. The present government has inherited a very strong fiscal framework, all due to good Liberal management. Prayers The one area that the Conservative government has failed on, and I am glad to see that the minister is here today, is the urban Ï (1005) community agenda. [English] In 1983 the Federation of Canadian Municipalities proposed an CRIMINAL CODE infrastructure program to deal with decaying infrastructure in (Bill C-376. On the Order. Private Members' Bills:) Canada. However, in 1984, the new Conservative government let it lay dormant for 10 years. I know something about this because I Second reading of Bill C-376, An Act to amend the Criminal was president of the Federation of Canadian Municipalities at one Code (impaired driving) and to make consequential amendments to time. other Acts—Mr. Ron Cannan. Mr. Tom Lukiwski (Parliamentary Secretary to the Leader of There seems to be a pattern here. When we came into office, we the Government in the House of Commons and Minister for brought in a national infrastructure program. We dealt with cities and Democratic Reform, CPC): Mr.