9 the British Alliance of 1812–14

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

DOCUMENT RESUME AUTHOR Sayers, Evelyn M., Ed. Indiana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 288 803 SO 018 629 AUTHOR Sayers, Evelyn M., Ed. TITLE Indiana: A Handbook for U.S. History Teachers. INSTITUTION Indiana State Dept. of Public Instruction, Indianapolis. SPONS AGENCY Indiana Committee for the Humanities, Indianapolis.; National Endowment for the Humanities (NFAH), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE 87 NOTE 228p. PUB TYPE Guides - Classroom Use Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS American Indian History; Archaeology; *Citizenship Education; Cultural Education; Curriculum Development; Curriculum Guides; Geography Instruction; Instructional Materials; Middle Schools; *Social Studies; State Government; *State History; *United States History IDENTIFIERS *Indiana; Northwest Territories ABSTRACT This handbook was developed to encourage more effective state citizenship through the teaching of state history. Attention is given to geographical factors, politics, government, social and economic changes, and cultural development. The student is introduced to the study of Indiana history with a discussion of the boundaries, topography, and geologic processes responsible for shaping the topography of the state. The handbook contains 16 chapters, each written by an expert in the field. The chapters are: (1) Indiana Geography; (2) Archaeology and Prehistory; (3) The Indians: Early Residents of Indiana, to 1679; (4) Indiana as Part of the French Colonial Domain, 1679-1765; (5) The Old Northwest under British Control, 1763-1783; (6) Indiana: A Part of the Old Northwest, 1783-1800; (7) The Old Northwest: Survey, Sale and Government; (8) Indiana Territory and Early Statehood, 1800-1825; (9) Indiana: The Nineteenth State, 1820-1877; (10) Indiana Society, 1865-1920; (11) Indiana Lifestyle, 1865-1920; (12) Indiana: 1920-1960; (13) Indiana since 1960; (14) Indiana Today--Manufacturing, Agriculture, and Recreation; (15) Indiana Government; and (16) Indiana: Economic Development Toward the 21st Century. -

War and Legitimacy: the Securement of Sovereignty in the Northwest Indian War

i ABSTRACT WAR AND LEGITIMACY: THE SECUREMENT OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE NORTHWEST INDIAN WAR During the post-revolution period, the newfound constitutional government of the United States faced a crisis of sovereignty and legitimacy. The Old Northwest region, encompassing what is now Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, was disputed between several groups. The U.S. government under George Washington claimed the region and sought to populate the land with white settlers, British officials in North America wished to reestablish British hegemony in the Ohio River valley and Native-Americans wished to protect their ancestral homeland from foreign invasion. In the 1790s, war broke out between a British backed alliance of Native tribes and the United States of America. Historians have named this conflict the Northwest Indian War. Examining government records, personal correspondences between Washington administration officials and military commanders, as well as recollections of soldiers, officials and civilians this thesis explores the geopolitical causes and ramifications of the Northwest Indian War. These sources demonstrate how the war was a reflection of a crisis which threatened the legitimacy to American sovereignty in the West. Furthermore, they also demonstrate how the use of a professional federal standing army was used by Washington’s government to secure American legitimacy. Michael Anthony Lipe August 2019 ii WAR AND LEGITIMACY: THE SECUREMENT OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE NORTHWEST INDIAN WAR by Michael Anthony Lipe A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno August 2019 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. -

Anthony Wayne M Em 0 R· I a L

\ I ·I ANTHONY WAYNE M EM 0 R· I A L 'I ' \ THE ANTHONY WAYNE MEMORIAL PARKWAY PROJECT . in OHIO -1 ,,,, J Compiled al tlze Request of the ANTHONY WAYNE MEMO RIAL LEGISLATIVE COMMITTEE by lhr O..H. IO STATE ARCHAEOLOGICAL and H ISTORICAL SOCIETY 0 00 60 4016655 2 I• Columbus, Ohio 1944 ' '.'-'TnN ~nd MONTGOMERY COt Jt-rt"-' =J1UC llBR.APV Acknowledgments . .. THE FOLLOWING ORGANIZATIONS ass isted lll the compilation of this booklet : The A nthony Wayne Memo ri al J oint L egislative Cammi ttee The Anthony \Vayne Memori al Associati on The! Toledo-Lucas County Planning Commiss ions The Ohio D epa1 rtment of Conservation and Natural Resources The Ohio Department of Highways \ [ 4 J \ Table of Contents I Anthony Wayne Portrait 1794_ ·---···-· ·--· _____ . ----------- ·----------------- -------------------. _____ Cover Anthony Wayne Portrait in the American Revolution ____________________________ F rrm I ispiece Ii I I The Joint Legislative Committee_______ --------····----------------------------------------------------- 7 i· '#" j The Artthony Wayne Memorial Association ___________________________________ .-------------------- 9 I· The Ohio Anthony Wayne Memorial Committee _____________________________________ ---------- 11 I I I Meetings of the Joint Legislative Committee·------·--------- -·---------------------------------- 13 I I "Mad Anthony" Wayne a'dd the Indian \Vars, 1790-179.'---------------------------------- 15 lI The Military Routes of Wa.yne, St. Clair, and Harmar, 1790-179-t- ___________ . _______ 27 I The Anthony Wayne Memorial -

River Raisin National Battlefield Park Lesson Plan Template

River Raisin National Battlefield Park 3rd to 5th Grade Lesson Plans Unit Title: “It’s Not My Fault”: Engaging Point of View and Historical Perspective through Social Media – The War of 1812 Battles of the River Raisin Overview: This collection of four lessons engage students in learning about the War of 1812. Students will use point of view and historical perspective to make connections to American history and geography in the Old Northwest Territory. Students will learn about the War of 1812 and study personal stories of the Battles of the River Raisin. Students will read and analyze informational texts and explore maps as they organize information. A culminating project will include students making a fake social networking page where personalities from the Battles will interact with one another as the students apply their learning in fun and engaging ways. Topic or Era: War of 1812 and Battles of River Raisin, United States History Standard Era 3, 1754-1820 Curriculum Fit: Social Studies and English Language Arts Grade Level: 3rd to 5th Grade (can be used for lower graded gifted and talented students) Time Required: Four to Eight Class Periods (3 to 6 hours) Lessons: 1. “It’s Not My Fault”: Point of View and Historical Perspective 2. “It’s Not My Fault”: Battle Perspectives 3. “It’s Not My Fault”: Character Analysis and Jigsaw 4. “It’s Not My Fault”: Historical Conversations Using Social Media Lesson One “It’s Not My Fault!”: Point of View and Historical Perspective Overview: This lesson provides students with background information on point of view and perspective. -

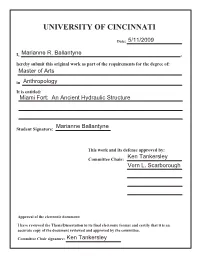

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5/11/2009 I, Marianne R. Ballantyne , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in Anthropology It is entitled: Miami Fort: An Ancient Hydraulic Structure Marianne Ballantyne Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Ken Tankersley Vern L. Scarborough Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Ken Tankersley Miami Fort: An Ancient Hydraulic Structure A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology of the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences 2009 Marianne R. Ballantyne B.A., University of Toledo 2007 Committee: Kenneth B. Tankersley, Chair Vernon L. Scarborough ABSTRACT Miami Fort, located in southwestern Ohio, is a multicomponent hilltop earthwork approximately nine kilometers in length. Detailed geological analyses demonstrate that the earthwork was a complex gravity-fed hydraulic structure, which channeled spring waters and surface runoff to sites where indigenous plants and cultigens were grown in a highly fertile but drought prone loess soil. Drill core sampling, x-ray diffractometry, high-resolution magnetic susceptibility analysis, and radiocarbon dating demonstrate that the earthwork was built after the Holocene Climatic Optimum and before the Medieval Warming Period. The results of this study suggest that these and perhaps other southern Ohio hilltop earthworks are hydraulic structures rather than fortifications. -

Northwest Ohio Quarterly Volume 16 Issue 2

Northwest Ohio Quarterly Volume 16 Issue 2 Toledo and Fort Miami UR general interest in the site of Fort Miami, located on the west bank of the Maumee River in Lucas County. wi thin the O corporate limits of the Village of Maumee, goes hack at least two generations. In the 1880's a movement was commenced by citizens of j\·faumcc Valley wh ich foreshadowed the activities of the present vigorous Maumee Scenic and H istoric Highway Association. At that time it was thought that solution lay in federal d evelopment of this and the other historic sites of northwestern Ohio. Surveys of these sites were made by U. S, Army engineers, pursuant to legis lation sponsored by Jacob Romcis of 'Toledo. The survey o f Fort "Miami in 1888 is reproduced in th is issue. Nothing came of this movement, however, and little was apparently done to reclaim lhe site from the pastoral scenes pictured in the illustrated section of this issue until the first World War. T h is movement subsided u nder the inflated realty prices of the times. The acti"e story, the begin· ning of the movement which finally saved the site for posterity, commences with the organization of the Maumee River Scenic and Historic Highway Association in 1939. The details of this fi ght are given in the October, 1942, issue of our Q UARTERLY, and can only be summarized here. The fo llowing names appear in the forefront: T he organizers of the Maumee River group, l\ofr. Ralph Peters, of the Defian ce Crescent·News, Mr. -

Your Guide to Indiana History

What’s A Hoosier? Your Guide to Indiana History Distributed by: State Rep. Karen Engleman [email protected] www.IndianaHouseRepublicans.com 1-800-382-9841 Table of Contents 3 Indiana Facts 4 Native American Heritage 5 Early Hoosiers and Statehood 7 Agriculture and the Hoosier Economy 8 Hoosier Contributions 9 Famous Hoosiers 10 History Scramble 11 Indiana History Quiz 12 Indiana History Quiz Continued 13 Answers to Quizzes Information for this booklet made possible from: www.indianahistory.org, IN.gov and Indiana: The World Around Us MacMillian/McGraw - Hill, 1991 Indiana Facts STATE FLAG STATE SEAL POPULATION The star above the torch The State Seal depicts a Indiana is the 15th stands for Indiana, which pioneer scene portraying largest state. According was the 19th state to how the early people of to the 2010 U.S. join the Union. The state Indiana overcame the Census, 6,483,802 colors are blue and gold. wilderness. The seal has Hoosiers live here. been in use since 1801, adopted until 1963. but it was not officially STATE BIRD STATE CAPITAL STATE FLOWER In 1933, the The capital of Indiana From 1931 to 1957, cardinal was is Indianapolis. The the zinnia was the selected as the state Statehouse is located bird by the Indiana in Indianapolis. In 1957, the Indiana General Assembly. stateGeneral flower Assembly of Indiana. Indiana capital from adopted the peony as Corydon1813 wasto 1825. the first the state flower. 3 Our Native American Heritage Indiana means “the land of the Indians.” Early Native Americans lived like nomads. A nomad is a person who moves from place to place in search of food. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE November 16, 1999 Here on This Floor

29838 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD—HOUSE November 16, 1999 here on this Floor. If we give China Gates and his company were applauded ory of tying. Now, if some competitor most-favored-nation status on a perma- for bringing yet more new wonderful comes along with a better browser, nent basis, then we will not be able to technology that will benefit all people frankly Microsoft can rapidly find react in any meaningful way. in this world. itself at the losing end of that competi- Madam Speaker, I have come to this Mr. Gates is a man who had a dream, tion, and there is no reason or ration- Floor three times, to vote in favor of a focus, a passion, an intelligence, and ale to apply the theory of tying one giving China most-favored-nation sta- the savvy which for 25 short years has product with another in the computer tus one more year, and a second year, revolutionized the computer industry. world; as Professor George Priest has and a third year, because I am not Today, because of Bill Gates and his so aptly stated. As such, the tradi- ready to use our most powerful weapon colleagues in the computer industry, tional tying theory, Professor Priest in the Chinese-U.S. trade relationship people like me, my family, my grand- argues, may be irrelevant in this case at this time. But it is a long way be- mother, my wife’s father, Hoosiers all because it simply did not apply to com- tween saying we are not willing to use over Indiana, and Americans every- puters. -

Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Electronic Theses and Dissertations Fogler Library Spring 5-8-2020 "The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812 Joseph R. Miller University of Maine, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd Part of the Canadian History Commons, Military History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Miller, Joseph R., ""The Men Were Sick of the Place" : Soldier Illness and Environment in the War of 1812" (2020). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 3208. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/etd/3208 This Open-Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “THE MEN WERE SICK OF THE PLACE”: SOLDIER ILLNESS AND ENVIRONMENT IN THE WAR OF 1812 By Joseph R. Miller B.A. North Georgia University, 2003 M.A. University of Maine, 2012 A DISSERTATION Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (in History) The Graduate School The University of Maine May 2020 Advisory Committee: Scott W. See, Professor Emeritus of History, Co-advisor Jacques Ferland, Associate Professor of History, Co-advisor Liam Riordan, Professor of History Kathryn Shively, Associate Professor of History, Virginia Commonwealth University James Campbell, Professor of Joint, Air War College, Brigadier General (ret) Michael Robbins, Associate Research Professor of Psychology Copyright 2020 Joseph R. -

Along the Ohio Trail

Along The Ohio Trail A Short History of Ohio Lands Dear Ohioan, Meet Simon, your trail guide through Ohio’s history! As the 17th state in the Union, Ohio has a unique history that I hope you will find interesting and worth exploring. As you read Along the Ohio Trail, you will learn about Ohio’s geography, what the first Ohioan’s were like, how Ohio was discovered, and other fun facts that made Ohio the place you call home. Enjoy the adventure in learning more about our great state! Sincerely, Keith Faber Ohio Auditor of State Along the Ohio Trail Table of Contents page Ohio Geography . .1 Prehistoric Ohio . .8 Native Americans, Explorers, and Traders . .17 Ohio Land Claims 1770-1785 . .27 The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 . .37 Settling the Ohio Lands 1787-1800 . .42 Ohio Statehood 1800-1812 . .61 Ohio and the Nation 1800-1900 . .73 Ohio’s Lands Today . .81 The Origin of Ohio’s County Names . .82 Bibliography . .85 Glossary . .86 Additional Reading . .88 Did you know that Ohio is Hi! I’m Simon and almost the same distance I’ll be your trail across as it is up and down guide as we learn (about 200 miles)? Our about the land we call Ohio. state is shaped in an unusual way. Some people think it looks like a flag waving in the wind. Others say it looks like a heart. The shape is mostly caused by the Ohio River on the east and south and Lake Erie in the north. It is the 35th largest state in the U.S. -

Laura Secord

THE CANADIAN ATLAS ONLINE NUNAVUT – GRADE 9 www.canadiangeographic.ca/atlas The Role of Women in the War of 1812: Laura Secord Lesson Overview In this lesson, students will investigate the role of Laura Secord in the War of 1812. They will explore the vital roles women played on the battlefields and assess the ways in which female participants have been compensated and remembered. Grade Level Grade 9 (can be modified for higher grades) Time Required Teachers should be able to conduct the lesson in one class. Curriculum Connection (Province/Territory and course) Nunavut -- Social Studies: Grade 9 • Students will demonstrate knowledge of the names of various British and French colonies and the conflicts between them. • Students will demonstrate knowledge of the essence of conflicts between colonial people and the British government. Additional Resources, Materials and Equipment Required • Access to a blackboard/whiteboard, data projector or chart paper and markers • Appendix A: Women and War (attached) • Appendix B: Laura Secord (attached) • Canadian Geographic War of 1812 poster-map • Access to the internet Websites: Historica Minute: Laura Secord http://www.histori.ca/minutes/minute.do?id=10118 Main Objective Students will understand the vital role that women played in the campaigns of the War of 1812. They will realize that victory would not have been possible without the women who worked behind the scenes. Learning Outcomes By the end of the lesson, students will be able to: • recognize and value the role of women in the War of 1812; • understand the lack of recognition and compensation many female participants encountered; • characterize and define the word ‘hero’; • indicate and locate the geographic area of the War of 1812. -

Download a Map Template at Brief Descriptions of Key Events That Took Place on the Major Bodies of Water

Table of Contents INTRODUCTION Message to Teachers In this guide, borders are defined in geographic, political, national, linguistic and cultural terms. and Introduction Page 2 Sometimes they are clearly defined and other times they are abstract, though still significant to the populations affected by them. During the War of 1812, borders were often unclear as Canada, the United States and the War of 1812 Today Page 2 no proper survey had been done to define the boundaries. Border decisions were made by government leaders and frequently led to decades of disagreements. When borders changed, Borders Debate Page 4 they often affected the people living on either side by determining their nationality and their ability to trade for goods and services. Integrating Geography and History Page 5 When Canadians think of the border today, they might think of a trip to the United States on War on the Waves Page 5 vacation, but the relationship between these bordering countries is the result of over 200 Battles and Borders in Upper and Lower Canada Page 6 years of relationship-building. During the War of 1812 the border was in flames and in need of defence, but today we celebrate the peace and partnership that has lasted since then. Post-War: The Rush-Bagot Agreement Page 6 CANADA, THE UNITED STATES AND the WaR OF TeachersMessage to This guide is designed to complement “Just two miles up the road, there’s a border crossing. Through it, thousands of people pass18 to and 12 from The Historica-Dominion Institute’s the United States every day.