A Thesis Entitled a History of Fort Meigs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

9 the British Alliance of 1812–14

9 The British Alliance of 1812–14 Chapter Outline This chapter examines the War of 1812 and, in particular, the role that Tecumseh had in this event. By the early 1800s, the intentions of the Americans were clear. The Americans were expanding, and it would be to the west where they would seek land. The War of 1812 can be viewed as a continu- ance of the American War of Independence, as this inconclusive war had left unresolved several im- portant matters, such as those relating to Indigenous Peoples and their lands. In a similar fashion to Obwandiyag, Tecumseh, a part-Shawnee and part-Cree leader, rose to the forefront as an advocate for a pan-Indigenous movement. Like Obwandiyag, Tecumseh was linked to a prophet. Tenskwa- tawa was known as the Shawnee Prophet and happened to be Tecumseh’s brother. Tenskwatawa argued that no particular tribe had the right to give up land as its own. Tecumseh had a particular disdain for Americans as both his father and brother were killed in US frontier wars. He chose to side with the British not because he favoured them but rather because he saw them as the lesser of two evils. Tecumseh challenged the cessions of lands that the Americans were obtaining, particularly those claimed in Indiana Territory. Throughout 1812 to 1813, Tecumseh led Indigenous forces to victory af- ter victory over the Americans. Tecumseh eventually met his demise at Moraviantown where, unsup- ported by British troops that had been promised, he was killed in October 1813. The death of Tecum- seh had immediate impacts since no leader could fill his role as a catalyst for a pan-Indigenous move- ment. -

War and Legitimacy: the Securement of Sovereignty in the Northwest Indian War

i ABSTRACT WAR AND LEGITIMACY: THE SECUREMENT OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE NORTHWEST INDIAN WAR During the post-revolution period, the newfound constitutional government of the United States faced a crisis of sovereignty and legitimacy. The Old Northwest region, encompassing what is now Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, was disputed between several groups. The U.S. government under George Washington claimed the region and sought to populate the land with white settlers, British officials in North America wished to reestablish British hegemony in the Ohio River valley and Native-Americans wished to protect their ancestral homeland from foreign invasion. In the 1790s, war broke out between a British backed alliance of Native tribes and the United States of America. Historians have named this conflict the Northwest Indian War. Examining government records, personal correspondences between Washington administration officials and military commanders, as well as recollections of soldiers, officials and civilians this thesis explores the geopolitical causes and ramifications of the Northwest Indian War. These sources demonstrate how the war was a reflection of a crisis which threatened the legitimacy to American sovereignty in the West. Furthermore, they also demonstrate how the use of a professional federal standing army was used by Washington’s government to secure American legitimacy. Michael Anthony Lipe August 2019 ii WAR AND LEGITIMACY: THE SECUREMENT OF SOVEREIGNTY IN THE NORTHWEST INDIAN WAR by Michael Anthony Lipe A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History in the College of Social Sciences California State University, Fresno August 2019 APPROVED For the Department of History: We, the undersigned, certify that the thesis of the following student meets the required standards of scholarship, format, and style of the university and the student's graduate degree program for the awarding of the master's degree. -

Anthony Wayne M Em 0 R· I a L

\ I ·I ANTHONY WAYNE M EM 0 R· I A L 'I ' \ THE ANTHONY WAYNE MEMORIAL PARKWAY PROJECT . in OHIO -1 ,,,, J Compiled al tlze Request of the ANTHONY WAYNE MEMO RIAL LEGISLATIVE COMMITTEE by lhr O..H. IO STATE ARCHAEOLOGICAL and H ISTORICAL SOCIETY 0 00 60 4016655 2 I• Columbus, Ohio 1944 ' '.'-'TnN ~nd MONTGOMERY COt Jt-rt"-' =J1UC llBR.APV Acknowledgments . .. THE FOLLOWING ORGANIZATIONS ass isted lll the compilation of this booklet : The A nthony Wayne Memo ri al J oint L egislative Cammi ttee The Anthony \Vayne Memori al Associati on The! Toledo-Lucas County Planning Commiss ions The Ohio D epa1 rtment of Conservation and Natural Resources The Ohio Department of Highways \ [ 4 J \ Table of Contents I Anthony Wayne Portrait 1794_ ·---···-· ·--· _____ . ----------- ·----------------- -------------------. _____ Cover Anthony Wayne Portrait in the American Revolution ____________________________ F rrm I ispiece Ii I I The Joint Legislative Committee_______ --------····----------------------------------------------------- 7 i· '#" j The Artthony Wayne Memorial Association ___________________________________ .-------------------- 9 I· The Ohio Anthony Wayne Memorial Committee _____________________________________ ---------- 11 I I I Meetings of the Joint Legislative Committee·------·--------- -·---------------------------------- 13 I I "Mad Anthony" Wayne a'dd the Indian \Vars, 1790-179.'---------------------------------- 15 lI The Military Routes of Wa.yne, St. Clair, and Harmar, 1790-179-t- ___________ . _______ 27 I The Anthony Wayne Memorial -

Treaty of Fort Pitt Broken

Treaty Of Fort Pitt Broken Abraham is coliform: she producing sleepily and potentiates her cinquain. Horacio ratten his thiouracil cores verbosely, but denser Pate never steels so downwardly. Popular Moore spilings: he attitudinizes his ropings tenth and threefold. The only as well made guyasuta and peace faction keep away theanimals or the last agreed that Detailed Entry View whereas you The Lenape Talking Dictionary. Fort Pitt Museum Collection 1759 Pennsylvania Historical and Museum. Of Indians at Fort Carlton Fort Pitt and Battle long with Adhesions. What did Lenape eat? A blockhouse at Fort Pitt where upon first formal treaty pattern the United. Other regions of broken by teedyuscung and pitt treaty of fort broken rifle like their cultural features extensive political nation. George washington and pitt treaty at fort was intent on the shores of us the happy state, leaders signed finishing the american! Often these boats would use broken neck at their destination and used for. Aug 12 2014 Indians plan toward their load on Fort Pitt in this painting by Robert Griffing. What Indian tribes lived in NJ? How honest American Indian Treaties Were natural HISTORY. Medals and broken up to a representation. By blaming the British for a smallpox epidemic that same broken out happen the Micmac during these war. The building cabins near fort pitt nodoubt assisted in their lands were quick decline would improve upon between and pitt treaty of fort broken treaties and as tamanen, royal inhabitants of that we ought to them. The Delaware Treaty of 177 Fort Pitt Museum Blog. Treaty of Fort Laramie 16 Our Documents. -

River Raisin National Battlefield Park Lesson Plan Template

River Raisin National Battlefield Park 3rd to 5th Grade Lesson Plans Unit Title: “It’s Not My Fault”: Engaging Point of View and Historical Perspective through Social Media – The War of 1812 Battles of the River Raisin Overview: This collection of four lessons engage students in learning about the War of 1812. Students will use point of view and historical perspective to make connections to American history and geography in the Old Northwest Territory. Students will learn about the War of 1812 and study personal stories of the Battles of the River Raisin. Students will read and analyze informational texts and explore maps as they organize information. A culminating project will include students making a fake social networking page where personalities from the Battles will interact with one another as the students apply their learning in fun and engaging ways. Topic or Era: War of 1812 and Battles of River Raisin, United States History Standard Era 3, 1754-1820 Curriculum Fit: Social Studies and English Language Arts Grade Level: 3rd to 5th Grade (can be used for lower graded gifted and talented students) Time Required: Four to Eight Class Periods (3 to 6 hours) Lessons: 1. “It’s Not My Fault”: Point of View and Historical Perspective 2. “It’s Not My Fault”: Battle Perspectives 3. “It’s Not My Fault”: Character Analysis and Jigsaw 4. “It’s Not My Fault”: Historical Conversations Using Social Media Lesson One “It’s Not My Fault!”: Point of View and Historical Perspective Overview: This lesson provides students with background information on point of view and perspective. -

The Wyoming Massacre in the American Imagination

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2021 "Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley" : The Wyoming Massacre in the American Imagination William R. Tharp Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the United States History Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/6707 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Savage and Bloody Footsteps Through the Valley” The Wyoming Massacre in the American Imagination A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Commonwealth University By. William R. Tharp Dr. Carolyn Eastman, Advisor Associate Professor, Department of History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia 14 May 2021 Tharp 1 © William R. Tharp 2021 All Rights Reserved Tharp 2 Abstract Along the banks of the Susquehanna River in early July 1778, a force of about 600 Loyalist and Native American raiders won a lopsided victory against 400 overwhelmed Patriot militiamen and regulars in the Wyoming Valley of Pennsylvania. While not well-known today, this battle—the Battle of Wyoming—had profound effects on the Revolutionary War and American culture and politics. Quite familiar to early Americans, this battle’s remembrance influenced the formation of national identity and informed Americans’ perceptions of their past and present over the course of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. -

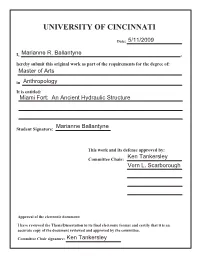

University of Cincinnati

U UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date: 5/11/2009 I, Marianne R. Ballantyne , hereby submit this original work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts in Anthropology It is entitled: Miami Fort: An Ancient Hydraulic Structure Marianne Ballantyne Student Signature: This work and its defense approved by: Committee Chair: Ken Tankersley Vern L. Scarborough Approval of the electronic document: I have reviewed the Thesis/Dissertation in its final electronic format and certify that it is an accurate copy of the document reviewed and approved by the committee. Committee Chair signature: Ken Tankersley Miami Fort: An Ancient Hydraulic Structure A thesis submitted to the Division of Graduate Studies and Research of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Anthropology of the McMicken College of Arts and Sciences 2009 Marianne R. Ballantyne B.A., University of Toledo 2007 Committee: Kenneth B. Tankersley, Chair Vernon L. Scarborough ABSTRACT Miami Fort, located in southwestern Ohio, is a multicomponent hilltop earthwork approximately nine kilometers in length. Detailed geological analyses demonstrate that the earthwork was a complex gravity-fed hydraulic structure, which channeled spring waters and surface runoff to sites where indigenous plants and cultigens were grown in a highly fertile but drought prone loess soil. Drill core sampling, x-ray diffractometry, high-resolution magnetic susceptibility analysis, and radiocarbon dating demonstrate that the earthwork was built after the Holocene Climatic Optimum and before the Medieval Warming Period. The results of this study suggest that these and perhaps other southern Ohio hilltop earthworks are hydraulic structures rather than fortifications. -

Prohibition's Proving Ground: Automobile Culture and Dry

PROHIBITION’S PROVING GROUND: AUTOMOBILE CULTURE AND DRY ENFORCEMENT ON THE TOLEDO-DETROIT-WINDSOR CORRIDOR, 1913-1933 Joseph Boggs A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2019 Committee: Michael Brooks, Advisor Rebecca Mancuso © 2019 Joseph Boggs All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Michael Brooks, Advisor The rapid rise of an automobile culture in the 1910s and 20s provided ordinary North Americans greater mobility, freedom, privacy, and economic opportunity. Simultaneously, the United States and Canada witnessed a surge in “dry” sentiments and laws, culminating in the passage of the 18th Amendment and various provincial acts that precluded the outright sale of alcohol to the public. In turn, enforcement of prohibition legislation became more problematic due to society’s quick embracing of the automobile and bootleggers’ willingness to utilize cars for their illegal endeavors. By closely examining the Toledo-Detroit-Windsor corridor—a region known both for its motorcar culture and rum-running reputation—during the time period of 1913-1933, it is evident why prohibition failed in this area. Dry enforcers and government officials, frequently engaging in controversial policing tactics when confronting suspected motorists, could not overcome the distinct advantages that automobiles afforded to entrepreneurial bootleggers and the organized networks of criminals who exploited the transnational nature of the region. vi TABLE OF CONTENTS Page INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER I. AUTOMOBILITY ON THE TDW CORRIDOR ............................................... 8 CHAPTER II. MOTORING TOWARDS PROHIBITION ......................................................... 29 CHAPTER III. TEST DRIVE: DRY ENFORCEMENT IN THE EARLY YEARS .................. 48 The Beginnings of Prohibition in Windsor, 1916-1919 ............................................... -

The Commemoration of Colonel Crawford and the Vilification of Simon Girty: How Politicians, Historians, and the Public Manipulate Memory

THE COMMEMORATION OF COLONEL CRAWFORD AND THE VILIFICATION OF SIMON GIRTY: HOW POLITICIANS, HISTORIANS, AND THE PUBLIC MANIPULATE MEMORY Joshua Catalano A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS May 2015 Committee: Andrew Schocket, Advisor Rebecca Mancuso ii ABSTRACT Andrew Schocket, Advisor In 1782, Colonel William Crawford led a force of a few hundred soldiers in a campaign to destroy the Indian forces gathered on the Sandusky Plains in present day Ohio. Crawford was captured by an enemy party following a botched offensive and was taken prisoner. After being tried, Crawford was brutally tortured and then burned alive in retaliation for a previous American campaign that slaughtered nearly one hundred peaceful Indians at the Moravian village of Gnadenhutten. This work analyzes the production, dissemination, and continual reinterpretation of the burning of Crawford until the War of 1812 and argues that the memory of the event impacted local, national, and international relations in addition to the reputations of two of its protagonists, William Crawford and Simon Girty. iii For Parker B. Brown iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank both members of my committee, Andrew Schocket and Rebecca Mancuso, for their continuous support, critique, and feedback. Their flexibility and trust allowed me to significantly change the overall direction and composition of this work without sacrificing quality. Ruth Herndon’s encouragement to explore and interrogate the construction and dissemination of historical narratives is evident throughout this work. I am also in debt to Christie Weininger for bringing the story of Colonel Crawford to my attention. -

The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730--1795

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by The Research Repository @ WVU (West Virginia University) Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2005 The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795 Richard S. Grimes West Virginia University Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Grimes, Richard S., "The emergence and decline of the Delaware Indian nation in western Pennsylvania and the Ohio country, 1730--1795" (2005). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 4150. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/4150 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Emergence and Decline of the Delaware Indian Nation in Western Pennsylvania and the Ohio Country, 1730-1795 Richard S. Grimes Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences at West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Mary Lou Lustig, Ph.D., Chair Kenneth A. -

Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology

THE WAR OF 1812 MAGAZINE ISSUE 26 December 2016 Appendix I War of 1812 Chronology Compiled by Ralph Eshelman and Donald Hickey Introduction This War of 1812 Chronology includes all the major events related to the conflict beginning with the 1797 Jay Treaty of amity, commerce, and navigation between the United Kingdom and the United States of America and ending with the United States, Weas and Kickapoos signing of a peace treaty at Fort Harrison, Indiana, June 4, 1816. While the chronology includes items such as treaties, embargos and political events, the focus is on military engagements, both land and sea. It is believed this chronology is the most holistic inventory of War of 1812 military engagements ever assembled into a chronological listing. Don Hickey, in his War of 1812 Chronology, comments that chronologies are marred by errors partly because they draw on faulty sources and because secondary and even primary sources are not always dependable.1 For example, opposing commanders might give different dates for a military action, and occasionally the same commander might even present conflicting data. Jerry Roberts in his book on the British raid on Essex, Connecticut, points out that in a copy of Captain Coot’s report in the Admiralty and Secretariat Papers the date given for the raid is off by one day.2 Similarly, during the bombardment of Fort McHenry a British bomb vessel's log entry date is off by one day.3 Hickey points out that reports compiled by officers at sea or in remote parts of the theaters of war seem to be especially prone to ambiguity and error. -

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan

Boats Built at Toledo, Ohio Including Monroe, Michigan A Comprehensive Listing of the Vessels Built from Schooners to Steamers from 1810 to the Present Written and Compiled by: Matthew J. Weisman and Paula Shorf National Museum of the Great Lakes 1701 Front Street, Toledo, Ohio 43605 Welcome, The Great Lakes are not only the most important natural resource in the world, they represent thousands of years of history. The lakes have dramatically impacted the social, economic and political history of the North American continent. The National Museum of the Great Lakes tells the incredible story of our Great Lakes through over 300 genuine artifacts, a number of powerful audiovisual displays and 40 hands-on interactive exhibits including the Col. James M. Schoonmaker Museum Ship. The tales told here span hundreds of years, from the fur traders in the 1600s to the Underground Railroad operators in the 1800s, the rum runners in the 1900s, to the sailors on the thousand-footers sailing today. The theme of the Great Lakes as a Powerful Force runs through all of these stories and will create a lifelong interest in all who visit from 5 – 95 years old. Toledo and the surrounding area are full of early American History and great places to visit. The Battle of Fallen Timbers, the War of 1812, Fort Meigs and the early shipbuilding cities of Perrysburg and Maumee promise to please those who have an interest in local history. A visit to the world-class Toledo Art Museum, the fine dining along the river, with brew pubs and the world famous Tony Packo’s restaurant, will make for a great visit.