The Political and Ecclesiastical Extent of Scottish Dalriada Pamela O’Neill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notice of a Celtic Cross-Shaft in Rothesay Churchyard

410 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY, APRIL 13, 1891. IV. NOTICE OF A CELTIC CROSS-SHAFT IN ROTHESAY CHURCHYARD. BY REV. J. KING HEWISON, M.A., F.S.A. SCOT. For many years there lay almost unnoticed, except by those who had a patrimonial interest in it, covering a grave in the Parish Churchyard of Kothesay rudela , y carved tombstone. Up till the present time an interesting vestige of the clan system lingere custoth n i sm whic nativd hol e familie f Buto s e retai havinn ni g their relatives buried in sections of the churchyard allocated to their names, such as the Neills (Macneils), Stewarts, MacAlisters, Mackurdys, MacGilchiarans, MacConachys, Bannatynes, McGilchatans, McGilmuns, othed an r families whose antique interesting names have unfortunately been Anglicised; and even incomers bearing any of these names have maintained some traditional righ sepulturf o t e with their clans there. Oe cla familyr nth n(o )e MacAlistergravth f o e e slalyings th sbwa , amid e profusioan th d worw no f grasno n e s beautifutraceth it s f o s l interlaced ornamentation were scarcely visible t I appeare. onle b yo t d a rough, crooked, silver-grey stone split froe finely-grainemth d mica- schis whicn i t northere hth e nIsl th f Butpare o f o te abounds faro S , . fortunately, it was the reverse, or less carved side of the slab which lay exposed to the weather, and thus left it unnoticed; but when I had it cleaned and turned over, its elaborately sculptured face indicated that it. -

View Preliminary Assessment Report Appendix C

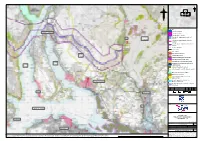

N N ? ? d c b a Legend Corrid or 4 e xte nts GARELOCHHEAD Corrid or 5 e xte nts Corrid or 4 & 5 e xte nts Corrid or 4 – ap p roxim ate c e ntre of A82 LOCH c orrid or LOMOND Corrid or 5 – ap p roxim ate c e ntre of c orrid or Corrid or 4 & 5 – ap p roxim ate c e ntre of c orrid or G A L iste d Build ing Gre at T rails Core Paths Sc he d ule d Monum e nt GLEN Conse rvation Are a FRUIN Gard e n and De signe d L and sc ap e Sp e c ial Prote c tion Are a (SPA) Sp e c ial Are a of Conse rvation (SAC) GARE LOCH W e tland s of Inte rnational Im p ortanc e LOCH (Ram sar Site s) LONG Anc ie nt W ood land Inve ntory Site of Sp e c ial Sc ie ntific Inte re st (SSSI) Marine Prote c te d Are a (MPA) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! National Sc e nic Are a L oc h L om ond and the T rossac hs National Park Flood Map p ing Coastal Exte nts – HELENSBURGH Me d ium L ike lihood Flood Map p ing Rive r Exte nts – Me d ium L ike lihood P01 12/02/2021 For Information TS RC SB DR Re v. Re v. Date Purp ose of re vision Orig/Dwn Che c kd Re v'd Ap p rv'd COVE BALLOCH Clie nt Proje c t A82 FIRTH OF CLYDE Drawing title FIGU RE C.2A PREL IMINARY ASSESSMENT CORRIDORS 4, 5 DUNOON She e t 01 of 04 Drawing Status Suitab ility FOR INFORMATION S2 Sc ale 1:75,000 @ A3 DO NOT SCALE Jac ob s No. -

James III and VIII

Gale Primary Sources Start at the source. James III and VIII Professor Edward Corp Université de Toulouse Bonnie Prince Charlie Entering the Ballroom at Holyroodhouse before 30 Apr 1892. Royal Collection Trust/ ©Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2018 EMPOWER™ RESEARCH The life story of James III and VIII is mainly contained Germain-en-Laye in France, James had good reason to within the Stuart Papers in the Royal Archives at be confident that he would one day be restored to the Windsor Castle. They contain thousands of documents thrones of his father. In the second (1719-66), when he in hundreds of volumes giving details of his political mainly lived at Rome, he increasingly doubted and and personal correspondence, of his finances, and of eventually knew that he would never be restored. The the management of his court. Yet it is important to turning point came during the five years from the recognise that the Stuart Papers provide a summer of 1714 to the summer of 1719, when James comprehensive account of the king's life only from the experienced a series of major disappointments and beginning of 1716, when he was 27 years old. They tell reverses which had a profound effect on his us very little about the period from his birth at personality. Whitehall Palace in June 1688 until he reached the age He had a happy childhood at Saint-Germain, where he of 25 in 1713, and not much about the next two years was recognised as the Prince of Wales and then, after from 1713 to the end of 1715. -

Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

;<>?3 ?3@@8393;@ 6; @53 6;;3> 530>623? 1/# *%%"&(%%- B6@5 ?=316/8 >343>3;13 @< @53 6?8/;2? <4 9A88! 1<88 /;2 @6>33 /OOG ># 7PJOSTPO / @JGSKS ?UDNKTTGF HPR TJG 2GIRGG PH =J2 CT TJG AOKVGRSKTY PH ?T# /OFRGWS &++& 4UMM NGTCFCTC HPR TJKS KTGN KS CVCKMCDMG KO >GSGCREJ.?T/OFRGWS,4UMM@GXT CT, JTTQ,$$RGSGCREJ"RGQPSKTPRY#ST"COFRGWS#CE#UL$ =MGCSG USG TJKS KFGOTKHKGR TP EKTG PR MKOL TP TJKS KTGN, JTTQ,$$JFM#JCOFMG#OGT$&%%'($'+)% @JKS KTGN KS QRPTGETGF DY PRKIKOCM EPQYRKIJT Norse settlement in the Inner Hebrides ca 800-1300 with special reference to the islands of Mull, Coll and Tiree A thesis presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Anne R Johnston Department of Mediaeval History University of St Andrews November 1990 IVDR E A" ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS None of this work would have been possible without the award of a studentship from the University of &Andrews. I am also grateful to the British Council for granting me a scholarship which enabled me to study at the Institute of History, University of Oslo and to the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs for financing an additional 3 months fieldwork in the Sunnmore Islands. My sincere thanks also go to Prof Ragni Piene who employed me on a part time basis thereby allowing me to spend an additional year in Oslo when I was without funding. In Norway I would like to thank Dr P S Anderson who acted as my supervisor. Thanks are likewise due to Dr H Kongsrud of the Norwegian State Archives and to Dr T Scmidt of the Place Name Institute, both of whom were generous with their time. -

Historic Arts and Crafts House with Separate Cottage and Views Over the Gare Loch

Historic Arts and Crafts house with separate cottage and views over the Gare Loch Ferry Inn, Rosneath, By Helensburgh, G84 0RS Lower ground floor: Sitting room, bedroom/gym, WC. Ground floor: Reception hall, drawing room, dining room, kitchen, study, morning room, pantry First floor: Principal bedroom with en suite bathroom, 3 further bedrooms, 2 further bathrooms. Ferry Inn Cottage: Detached cottage with living room/bedroom/bedroom, kitchen and shower room Garden & Grounds of around 4 acres. Local Information and both local authority and Ferry Inn is set in around 4 acres private schools. of its own grounds on the Rosneath Peninsula. The grounds The accessibility of the Rosneath form the corner of the promontory Peninsula has been greatly on the edge of Rosneath which improved by the opening of the juts out into the sea loch. There new Ministry of Defence road are magnificent views from the over the hills to Loch Lomond. house over the loch and to the The journey time to Loch marina at Rhu on the opposite. Lomond, the Erskine Bridge and Glasgow Airport has been The Rosneath Peninsula lies to significantly reduced by the new the north of the Firth of Clyde. road which bypasses Shandon, The peninsula is reached by the Rhu and Helensburgh on the road from Garelochhead in its A814 on the other side of the neck to the north. The peninsula loch. is bounded by Loch Long to the northwest, Gare Loch to the east About this property and the Firth of Clyde to the south The original Ferry Inn stood next and is connected to the mainland to the main jetty for the ferry by a narrow isthmus at its which ran between Rosneath and northern end. -

Argyll Bird Report with Sstematic List for the Year

ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Volume 15 (1999) PUBLISHED BY THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB Cover picture: Barnacle Geese by Margaret Staley The Fifteenth ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Edited by J.C.A. Craik Assisted by P.C. Daw Systematic List by P.C. Daw Published by the Argyll Bird Club (Scottish Charity Number SC008782) October 1999 Copyright: Argyll Bird Club Printed by Printworks Oban - ABOUT THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 19x5. Its main purpose is to play an active part in the promotion of ornithology in Argyll. It is recognised by the Inland Revenue as a charity in Scotland. The Club holds two one-day meetings each year, in spring and autumn. The venue of the spring meeting is rotated between different towns, including Dunoon, Oban. LochgilpheadandTarbert.Thc autumn meeting and AGM are usually held in Invenny or another conveniently central location. The Club organises field trips for members. It also publishes the annual Argyll Bird Report and a quarterly members’ newsletter, The Eider, which includes details of club activities, reports from meetings and field trips, and feature articles by members and others, Each year the subscription entitles you to the ArgyZl Bird Report, four issues of The Eider, and free admission to the two annual meetings. There are four kinds of membership: current rates (at 1 October 1999) are: Ordinary E10; Junior (under 17) E3; Family €15; Corporate E25 Subscriptions (by cheque or standing order) are due on 1 January. Anyonejoining after 1 Octoberis covered until the end of the following year. -

Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish History1

The Scottish Historical Review, Volume LXXXV, 1: No. 219: April 2006, 1–27 MATTHEW H. HAMMOND Ethnicity and the Writing of Medieval Scottish history1 ABSTRACT Historians have long tended to define medieval Scottish society in terms of interactions between ethnic groups. This approach was developed over the course of the long nineteenth century, a formative period for the study of medieval Scotland. At that time, many scholars based their analysis upon scientific principles, long since debunked, which held that medieval ‘peoples’ could only be understood in terms of ‘full ethnic packages’. This approach was combined with a positivist historical narrative that defined Germanic Anglo-Saxons and Normans as the harbingers of advances in Civilisation. While the prejudices of that era have largely faded away, the modern discipline still relies all too often on a dualistic ethnic framework. This is particularly evident in a structure of periodisation that draws a clear line between the ‘Celtic’ eleventh century and the ‘Norman’ twelfth. Furthermore, dualistic oppositions based on ethnicity continue, particu- larly in discussions of law, kingship, lordship and religion. Geoffrey Barrow’s Robert Bruce and the Community of the Realm of Scotland, first published in 1965 and now available in the fourth edition, is proba- bly the most widely read book ever written by a professional historian on the Middle Ages in Scotland.2 In seeking to introduce the thirteenth century to such a broad audience, Barrow depicted Alexander III’s Scot- land as fundamentally -

Kilchattan Bay - Rhubodach Via Rothesay from 21 October 2019

Kilchattan Bay - Rhubodach via Rothesay from 21 October 2019 490/90 Kilchattan Bay - Rhubodach Monday to Friday Winter Note: NSch Sch Sch NSch Sch NSch Sch Sch NSch Sch Sch Sch Sch Sch Notes: b Service: 490 490 490 490 90 90 490 490 490 90 490 490 90 90 90 90 Kilchattan Bay 0800 0800 0825 Kingarth 0805 0805 0829 Kerrycroy 0812 0812 0836 Ascog 0814 0814 0838 Montford 0740 0740 0816 0816 0840 Craigmore Pier 0742 0742 0819 0818 0842 Guildford Square, Arr (arr) - - 0825 - 0845 Joint Campus - - 0830 0832 - 0853 0854 0904 Victoria Annexe - - 0833 - 0855 0905 Guildford Square, Arr (arr) 0745 0745 0840 0821 0859 0909 Guildford Square, Dep (dep) 0615 0700 0745 0745 0815 0819 0819 0840 0845 0903 0910 Outside Depot 0622 0707 0752 0752 0802 0822 0826 0826 0847 0852 0910 0914 Port Bannatyne 0624 0709 0754 0754 0804 0824 0828 0828 0849 0854 Ettrick Bay - 0810 - - Rhubodach 0804 0838 0838 Note: Sch NSch Sch NSch Sch Service: 90 490 490 90 490 90 490 90 490 90 490 90 490 490 90 490 Kilchattan Bay 0912 1012 1112 1216 1316 1416 Kingarth 0917 1017 1117 1221 1321 1421 Kerrycroy 0926 1026 1126 1230 1330 1430 Ascog 0928 1028 1128 1232 1332 1432 Montford 0930 1030 1130 1234 1334 1434 Craigmore Pier 0932 1032 1132 1236 1336 1436 Joint Campus - - - - - - 1510 1540 Victoria Annexe - - - - - - 1511 1541 Guildford Square, Arr (arr) 0935 1035 1135 1239 1339 1439 1515 1545 Guildford Square, Dep (dep) 0915 0945 0945 1015 1045 1117 1150 1224 1250 1325 1350 1430 1445 1515 1517 1545 Outside Depot 0922 0952 0952 1022 1052 1124 1157 1231 1257 1332 1357 1437 1452 1522 1524 -

Kingdom of Strathclyde from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Kingdom of Strathclyde From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Strathclyde (lit. "Strath of the Clyde"), originally Brythonic Ystrad Clud, was one of the early medieval kingdoms of the Kingdom of Strathclyde Celtic people called the Britons in the Hen Ogledd, the Teyrnas Ystrad Clut Brythonic-speaking parts of what is now southern Scotland and northern England. The kingdom developed during the ← 5th century–11th → post-Roman period. It is also known as Alt Clut, the Brythonic century name for Dumbarton Rock, the medieval capital of the region. It may have had its origins with the Damnonii people of Ptolemy's Geographia. The language of Strathclyde, and that of the Britons in surrounding areas under non-native rulership, is known as Cumbric, a dialect or language closely related to Old Welsh. Place-name and archaeological evidence points to some settlement by Norse or Norse–Gaels in the Viking Age, although to a lesser degree than in neighbouring Galloway. A small number of Anglian place-names show some limited settlement by incomers from Northumbria prior to the Norse settlement. Due to the series of language changes in the area, it is not possible to say whether any Goidelic settlement took place before Gaelic was introduced in the High Middle Ages. After the sack of Dumbarton Rock by a Viking army from Dublin in 870, the name Strathclyde comes into use, perhaps reflecting a move of the centre of the kingdom to Govan. In the same period, it was also referred to as Cumbria, and its inhabitants as Cumbrians. During the High Middle Ages, the area was conquered by the Kingdom of Alba, becoming part of The core of Strathclyde is the strath of the River Clyde. -

Historic Argyll

HISTORIC ARGYLL Past editions are available, price £4 including postage. Please email [email protected] for details We are in the process of scanning older journals and making them available online. Contents of Past Editions 2015 The origins of some of the Kintyre McConachys Estates & their management in the nineteenth century Scottish Highlands & Islands The Lorn Combination Poorhouse The River that flows to Australia St Conan’s Kirk, Lochawe New evidence for the earliest inhabitants of Argyll Carn Mhic Dhonnchaidh 2014 The Inverary herring fleet of 1799 Archaeology in the Udal, North Uist Shipwreck at Connel Ferry Rev Gregor McGregor (1797 – 1885) – Lismore & Appin David Livingstone & his picture of Africa The kirkton of Muckairn Place names & folk tales of mid Lorn Carnasserie castle, Ardsceodnish, Argyll Clan Historian, Genealogist or Spin Doctor? 2013 LAHS – the first 50 years Bronze Age domestric settlements in Argyll Excavation of deserted settlement at Morlaggan Possible oban runes Delving into Dunollie The Rise & Fall of the Slate industry on the Slate islands 2012 Glenshallach through the ages Haakon’s expedition, 1263 Archaeology & the battle of Culloden The Scottish kelp industry Keeping the peace on Lismore Our postal past A cartographic journey through Lorn over 4 centuries 2011 (available online) 2. The Committee and office bearers 3. A Voyage in Search of Hinba. Robert Rae 12. Stirling Castle Palace Project. Kirsty Owen 17. A Factor's Lot. Martin Petrie 21. Medieval Kilbride. Catherine Gilles 27. The Brandystone. Lake Falconer 31. Book Review. Charles Hunter 33. Another one gone! Martin Petrie 35. 'Between the Burn and the Turning Sea' The story of Cadderlie. -

Gare Loch Loch Eck Loch Striven Firth of Clyde Loch

N LOCH ECK N ? ? c GARELOCHHEAD GLEN b a FINART Legend Corrid or 6 e xte nts Corrid or 7 e xte nts GLEN Corrid or 6 & 7 e xte nts FRUIN Corrid or 6 – ap p roxim ate c e ntre of c orrid or Corrid or 7 – ap p roxim ate c e ntre of GARE c orrid or LOCH LOCH Corrid or 6 & 7 – ap p roxim ate c e ntre of LOCH LONG c orrid or TARSAN G A L iste d Build ing Gre at T rails Core Paths Sc he d ule d Monum e nt Conse rvation Are a Gard e n and De signe d L and sc ap e Sp e c ial Prote c tion Are a (SPA) HELENSBURGH Sp e c ial Are a of Conse rvation (SAC) W e tland s of Inte rnational Im p ortanc e (Ram sar Site s) GLEN Anc ie nt W ood land Inve ntory LEAN Site of Sp e c ial Sc ie ntific Inte re st (SSSI) COVE Marine Prote c te d Are a (MPA) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! National Sc e nic Are a L oc h L om ond and the T rossac hs National Park Flood Map p ing Coastal Exte nts – Me d ium L ike lihood Flood Map p ing Rive r Exte nts – Me d ium L ike lihood FIRTH OF CLYDE P01 12/02/2021 For Information TS RC SB DR Re v. Re v. Date Purp ose of re vision Orig/Dwn Che c kd Re v'd Ap p rv'd LOCH STRIVEN Clie nt DUNOON Proje c t GREENOCK Drawing title FIGU RE C.3A PREL IMINARY ASSESSMENT CORRIDORS 6, 7 She e t 01 of 03 Drawing Status Suitab ility FOR INFORMATION S2 Sc ale 1:75,000 @ A3 DO NOT SCALE Jac ob s No. -

Determination of the Off-Site Emergency Planning and Prior Information Areas for HM Naval Base Clyde (Faslane)

[Type text] Commodore M E Gayfer ADC Royal Navy Naval Base Commander (Clyde) Lomond Building Her Majesty’s Naval Base Clyde Redgrave Court Merton Road Helensburgh Bootle Argyll and Bute Merseyside L20 7HS G84 8HL Telephone: Email: Our Reference: TRIM Ref: 2017/22779 Unique Number: CNB70127 Date: 28th February 2017 RADIATION (EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS AND PUBLIC INFORMATION) REGULATIONS 2001 (REPPIR) – HMNB CLYDE (FASLANE) EMERGENCY PLANNING AND PRIOR INFORMATION AREAS Dear Commodore Gayfer, As you are aware, ONR has been re-determining the REPPIR off-site emergency planning area(1) and the area within which prior information shall be provided to the public(2) around the HMNB Clyde (Faslane) DNSR Authorised Site as prescribed in REPPIR regulations 9(1) and 16(1) respectively. On behalf of the Ministry of Defence (MOD), Naval Base Commander (Clyde) (NBC) has made a declaration to ONR that there is no change to the circumstances that might affect its Report of Assessment (RoA) for the naval submarine reactor plant. Our re-determination has been made in accordance with ONR’s principles and guidance for the determination(3) of such areas and this letter is to inform Navy Command, as the MOD duty-holder with responsibility under REPPIR for supplying prior information to members of the public around the HMNB Clyde (Faslane) DNSR Authorised Site, of the following: 1. ONR notes that, in accordance with the requirements of regulations 5 and 6, NBC has reviewed its Hazard Identification and Risk Evaluation (HIRE) and Report of Assessment (RoA) for the naval submarine reactor plant, and has submitted to ONR a declaration of no change of circumstances, as provided for under regulation 5(2).