Anne R Johnston Phd Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Argyll & Bute M&G

Argyll & Bute M&G 15/09/2017 09:54 Page 1 A to Tarbert to Port Bannatyne Frequency in minutes Campbeltown 8 3 Ring and Ride Campbeltown Rothesay T operates throughout A 443 BUS and COACH SERVICES Mondays R this map B 449 90 . E L 0 250 500 metres Rothesay P R 477 Guildford Square Y Service to Fridays Saturdays Sundays T 926 Bay R E Please note that the frequency of services generally applies to school terms. During school holidays T to H terminating: T ILL R 0 200 400 yards 479 A A S O B Ascog, Number Operator Route Days Eves Days Eves ID A R E A 490 G 90.477.479.488 .491.492 some services are reduced and these frequencies are shown in brackets, for example "4(2) jnys" CRAIG K C . Mount Stuart D G NO A Y T ROA OW CK D L calling: S Calton SC E 493 and Kilchattan D RD AL M E S . BE Y E shows that there are 4 journeys during school terms and 2 journeys during school holidays. R S 490.493 C Bay 471 TSS Tighnabruaich - Kames (Tues & Thurs only) 4(5) jnys - - - - VE T R 90 A . W D T N 100 I D W 100 A EST . R R . L LAND E 488 R AR 440 A S ROA E P E D Tighnabruaich - Portavadie (Tues & Thurs only) 2 jnys - - - - A UA Y T T 440 N S V Frequency in minutes A ST 100. A 490 V D . E A 300 A A . -

Mull, Iona and Ulva Core Paths 2015

Argyll & Bute Council: Mull, Iona and Ulva Core Paths 2015 English Gaelic Ardmore costal path, Mishnish Ceum-Oirthir na h-Àirde Mòire, Maoisnis Ardtun to Bunessan link, Mull Àird Tunna do cheangal Bhun Easain, Muile Ballie Mhor to Culbuirg dunes, Iona Am Baile Mòr do dhùin-ghainmhich Chùl Bhuirg, Eilean Ì Breadalbane Street, School - Middle Brae Sràid Bhràghaid Albainn, Sgoil - Bruthach Meadhanach Bunessan Shore Road, Mull Rathad Cladach Bhun Easain, Muile Bunessan to Ardtun, Mull Bun Easain do dh'Àird Tunna, Muile Bunessan to Uisken, Mull Bun Easain do dh'Uisgean, Muile Burg Walk, Mull Ceum Bhuirg, Muile Calgary Pier Walk Ceum Cidhe Chalgairidh Carsaig Arches, Carsaig Bay, Mull Boghachan Chàrsaig, Camas Chàrsaig, Muile Carsaig Arches, Mull Boghachan Chàrsaig, Muile Coille an Fhraoich Mhoir, Craignure Coille an Fhraoich Mhòir, Creag an Iubhair Coille na Sroine, Salen, Mull Coille na Sròine, An Sàilean, Muile Craignure Pier to Java House Cidhe Chreag an Iubhair do Thaigh Java Croggan to Portfield, Loch Spelvie An Crògan do dh'Achadh a' Phuirt, Loch Speilbh Cuilbuirg Dunes to Port na Curaich, Iona Dùn-ghainmhich Chùl Bhùirg do Phort a' Churaich, Eilean Ì Dun Ara Castle, Glen Gorm Càisteal Dùn Àra, An Gleann Gorm Eas Brae, Main Street, Tobermory Bruthach an Eas, Prìomh Shràid, Tobar Mhoire Erray House to Rairaig, Tobermory, Mull Taigh na h-Eirbhe do Rèaraig, Tobar Mhoire, Muile Garmony Coastal Path Ceum-Oirthir a' Gharbh-Mhòine Glen Aros, Mull Gleann Àrois, Muile Killiechronan to Glenaros Farm, Mull Coille Chrònain do Thuathanas Ghlinn Àrois, Muile Killiechronan to Salen, Mull Coille Chrònain don t-Sàilean, Muile Ceangal Loch Frìosa, a’ Ghlinne Ghuirm, na h-Àirde Mòire, Lochfrisa, glengorm, ardmore, Tobermory link Thobar Mhoire North Beach Walk Iona Ceum na Tràghad a Tuath, Eilean Ì Pottie Circular, Fionnphort Cuairt-rathad Phoit Ì, Fionnphort 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. -

Wolves and Humans in Glen Affric: Public Attitudes and Knowledge by Kevin Cummings

The Newsletter of The Wolves and Humans Foundation No. 29, Summer 2013 Wolves and Humans in Glen Affric: Public attitudes and knowledge by Kevin Cummings Glen Affric, Scotland Photo: R Morley Kevin Cummings is Conservation Officer at Glamis Apart from the ecological impact of such a Castle Estate in Angus, Scotland. Having reintroduction, there is also the question of how the previously worked as a volunteer at the Scottish local communities would react. Seeking an answer Deer Centre, he completed his MSc in is what took me 130 miles to the Glen Affric area Conservation and Management of Protected Areas of the Highlands, to a small village called Cannich. in January 2013, with a thesis on public attitudes I would call a dilapidated caravan there my home and knowledge about wolves in the Glen Affric for a spell during one of the wettest summers on area of the Scottish Highlands. Here Kevin record while I conducted the research for my outlines some of the main findings of his research Master of Science degree in Conservation and and recounts his experiences carrying out Management at Edinburgh Napier University. interviews with local people. It is widely accepted that when the subject of he reintroduction of large predators to an reintroducing a predator to an area is raised, area where they have become extirpated is livestock farmers and hunting estate owners tend to Ta very complex issue. The Highlands of have a negative opinion towards it. I decided I Scotland is an area where the possibility of would try and discover how those not directly reintroducing a predator such as wolf or lynx has involved in farming and hunting feel a wolf been tentatively raised from time to time. -

2020 Cruise Directory Directory 2020 Cruise 2020 Cruise Directory M 18 C B Y 80 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−− 17 −−−−−−−−−−−−−−−

2020 MAIN Cover Artwork.qxp_Layout 1 07/03/2019 16:16 Page 1 2020 Hebridean Princess Cruise Calendar SPRING page CONTENTS March 2nd A Taste of the Lower Clyde 4 nights 22 European River Cruises on board MS Royal Crown 6th Firth of Clyde Explorer 4 nights 24 10th Historic Houses and Castles of the Clyde 7 nights 26 The Hebridean difference 3 Private charters 17 17th Inlets and Islands of Argyll 7 nights 28 24th Highland and Island Discovery 7 nights 30 Genuinely fully-inclusive cruising 4-5 Belmond Royal Scotsman 17 31st Flavours of the Hebrides 7 nights 32 Discovering more with Scottish islands A-Z 18-21 Hebridean’s exceptional crew 6-7 April 7th Easter Explorer 7 nights 34 Cruise itineraries 22-97 Life on board 8-9 14th Springtime Surprise 7 nights 36 Cabins 98-107 21st Idyllic Outer Isles 7 nights 38 Dining and cuisine 10-11 28th Footloose through the Inner Sound 7 nights 40 Smooth start to your cruise 108-109 2020 Cruise DireCTOrY Going ashore 12-13 On board A-Z 111 May 5th Glorious Gardens of the West Coast 7 nights 42 Themed cruises 14 12th Western Isles Panorama 7 nights 44 Highlands and islands of scotland What you need to know 112 Enriching guest speakers 15 19th St Kilda and the Outer Isles 7 nights 46 Orkney, Northern ireland, isle of Man and Norway Cabin facilities 113 26th Western Isles Wildlife 7 nights 48 Knowledgeable guides 15 Deck plans 114 SuMMER Partnerships 16 June 2nd St Kilda & Scotland’s Remote Archipelagos 7 nights 50 9th Heart of the Hebrides 7 nights 52 16th Footloose to the Outer Isles 7 nights 54 HEBRIDEAN -

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY of Macdhubhsith

THE MYTHOLOGY, TRADITIONS and HISTORY OF MacDHUBHSITH ― MacDUFFIE CLAN (McAfie, McDuffie, MacFie, MacPhee, Duffy, etc.) VOLUME 2 THE LANDS OF OUR FATHERS PART 2 Earle Douglas MacPhee (1894 - 1982) M.M., M.A., M.Educ., LL.D., D.U.C., D.C.L. Emeritus Dean University of British Columbia This 2009 electronic edition Volume 2 is a scan of the 1975 Volume VII. Dr. MacPhee created Volume VII when he added supplemental data and errata to the original 1792 Volume II. This electronic edition has been amended for the errata noted by Dr. MacPhee. - i - THE LIVES OF OUR FATHERS PREFACE TO VOLUME II In Volume I the author has established the surnames of most of our Clan and has proposed the sources of the peculiar name by which our Gaelic compatriots defined us. In this examination we have examined alternate progenitors of the family. Any reader of Scottish history realizes that Highlanders like to move and like to set up small groups of people in which they can become heads of families or chieftains. This was true in Colonsay and there were almost a dozen areas in Scotland where the clansman and his children regard one of these as 'home'. The writer has tried to define the nature of these homes, and to study their growth. It will take some years to organize comparative material and we have indicated in Chapter III the areas which should require research. In Chapter IV the writer has prepared a list of possible chiefs of the clan over a thousand years. The books on our Clan give very little information on these chiefs but the writer has recorded some probable comments on his chiefship. -

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-Names and Society: Analysis of the Medieval Districts of Forsa and Moloros in the Parish of Torosay, Mull

Whyte, Alasdair C. (2017) Settlement-names and society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. PhD thesis. http://theses.gla.ac.uk/8224/ Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten:Theses http://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Settlement-Names and Society: analysis of the medieval districts of Forsa and Moloros in the parish of Torosay, Mull. Alasdair C. Whyte MA MRes Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Celtic and Gaelic | Ceiltis is Gàidhlig School of Humanities | Sgoil nan Daonnachdan College of Arts | Colaiste nan Ealain University of Glasgow | Oilthigh Ghlaschu May 2017 © Alasdair C. Whyte 2017 2 ABSTRACT This is a study of settlement and society in the parish of Torosay on the Inner Hebridean island of Mull, through the earliest known settlement-names of two of its medieval districts: Forsa and Moloros.1 The earliest settlement-names, 35 in total, were coined in two languages: Gaelic and Old Norse (hereafter abbreviated to ON) (see Abbreviations, below). -

Download the .Pdf

Regional Archaeological Research Framework for Argyll: Chapter 7 http://www.scottishheritagehub.com/rarfa/ironage Appendix 1: Excavated Forts, Duns and Brochs in Argyll (ordered by date of first excavation) Site Name Type NMRS No. Location First Other References Excavated Years Dun Mac Sniachan fort NM93NW 2 Lorn 1873 1874 Smith 1875 Dun Boraige Mor broch NL94NW 1 Tiree 1880 Piggot 1952 Dun Mor Vaul broch NM04NW 3 Tiree 1880 1962-4 MacKie 1974, 1997 Suidhe Chennaidh dun NN02SW 1 Lorn 1890 Christison 1891 Leccamore/South dun NM171SE 2 Lorn 1890 1892 MacNaughton; 1891, 1893 Dun an Fheurain dun NM82NW 9 Lorn 1895 1950, Anderson 1895a; Ritchie 1974 1963 Dun Nighean dun NL94SE 1 Tiree 1881 Sands 1882 Dun na Cleite dun NL93NE 5 Tiree 1881 Sands 1882 Ardifuir dun NR79NE 2 Mid Argyll 1904 Christison 1905 Druim and Duin dun NR79SE 1 Mid Argyll 1904 Christison 1905 Duntroon fort NR89NW 10 Mid Argyll 1904 Christison 1905; Craw 1930; Lane and Campbell 2000 Dunadd fort NR89SW 1 Mid Argyll 1904 1905, Christison 1905 1929, Dunagoil fort NS056SE 4 Bute 1913 19801914-1 Mann 1915; Mann 1925; Harding 2004b 15, 1919, 1925 Section 7: The Iron Age Page 1 Regional Archaeological Research Framework for Argyll: Chapter 7 http://www.scottishheritagehub.com/rarfa/ironage Site Name Type NMRS No. Location First Other References Excavated Years Dun Breac dun NR85NE 17 Kintyre 1914 Graham 1915 Clachan Ard dun NS05NW 3 Bute 1933 MacCallum; 1959, 1963 Eilean Buidhe dun NS07NW 4 Bute 1936 Maxwell 1941 Kildonan Bay dun NR72NE 5 Kintyre 1936 1937-38 Fairhurst 1939; Peltonberg -

Sound of Gigha Proposed Special Protection Area (Pspa) NO

Sound of Gigha Proposed Special Protection Area (pSPA) NO. UK9020318 SPA Site Selection Document: Summary of the scientific case for site selection Document version control Version and Amendments made and author Issued to date and date Version 1 Formal advice submitted to Marine Scotland on Marine draft SPA. Nigel Buxton & Greg Mudge. Scotland 10/07/14 Version 2 Updated to reflect change in site status from draft Marine to proposed and addition of SPA reference Scotland number in preparation for possible formal 30/06/15 consultation. Shona Glen, Tim Walsh & Emma Philip Version 3 Creation of new site selection document. Emma Susie Whiting Philip 17/05/16 Version 4 Document updated to address requirements of Greg revised format agreed by Marine Scotland. Mudge Kate Thompson & Emma Philip 17/06/16 Version 5 Quality assured Emma Greg Mudge Philip 17/6/16 Version 6 Final draft for approval Andrew Emma Philip Bachell 22/06/16 Version 7 Final version for submission to Marine Scotland Marine Scotland, 24/06/16 Contents 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Site summary ........................................................................................................ 2 3. Bird survey information ....................................................................................... 5 4. Assessment against the UK SPA Selection Guidelines .................................... 6 5. Site status and boundary ................................................................................. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

The Norse Influence on Celtic Scotland Published by James Maclehose and Sons, Glasgow

i^ttiin •••7 * tuwn 1 1 ,1 vir tiiTiv^Vv5*^M òlo^l^!^^ '^- - /f^K$ , yt A"-^^^^- /^AO. "-'no.-' iiuUcotettt>tnc -DOcholiiunc THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND PUBLISHED BY JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS, GLASGOW, inblishcre to the anibersitg. MACMILLAN AND CO., LTD., LONDON. New York, • • The Macmillan Co. Toronto, • - • The Mactnillan Co. of Canada. London, • . - Simpkin, Hamilton and Co. Cambridse, • Bowes and Bowes. Edinburgh, • • Douglas and Foults. Sydney, • • Angus and Robertson. THE NORSE INFLUENCE ON CELTIC SCOTLAND BY GEORGE HENDERSON M.A. (Edin.), B.Litt. (Jesus Coll., Oxon.), Ph.D. (Vienna) KELLY-MACCALLUM LECTURER IN CELTIC, UNIVERSITY OF GLASGOW EXAMINER IN SCOTTISH GADHELIC, UNIVERSITY OF LONDON GLASGOW JAMES MACLEHOSE AND SONS PUBLISHERS TO THE UNIVERSITY I9IO Is buaine focal no toic an t-saoghail. A word is 7nore lasting than the world's wealth. ' ' Gadhelic Proverb. Lochlannaich is ànnuinn iad. Norsemen and heroes they. ' Book of the Dean of Lismore. Lochlannaich thi'eun Toiseach bhiir sgéil Sliochd solta ofrettmh Mhamiis. Of Norsemen bold Of doughty mould Your line of oldfrom Magnus. '' AIairi inghean Alasdair Ruaidh. PREFACE Since ever dwellers on the Continent were first able to navigate the ocean, the isles of Great Britain and Ireland must have been objects which excited their supreme interest. To this we owe in part the com- ing of our own early ancestors to these isles. But while we have histories which inform us of the several historic invasions, they all seem to me to belittle far too much the influence of the Norse Invasions in particular. This error I would fain correct, so far as regards Celtic Scotland. -

Argyll Bird Report with Sstematic List for the Year

ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Volume 15 (1999) PUBLISHED BY THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB Cover picture: Barnacle Geese by Margaret Staley The Fifteenth ARGYLL BIRD REPORT with Systematic List for the year 1998 Edited by J.C.A. Craik Assisted by P.C. Daw Systematic List by P.C. Daw Published by the Argyll Bird Club (Scottish Charity Number SC008782) October 1999 Copyright: Argyll Bird Club Printed by Printworks Oban - ABOUT THE ARGYLL BIRD CLUB The Argyll Bird Club was formed in 19x5. Its main purpose is to play an active part in the promotion of ornithology in Argyll. It is recognised by the Inland Revenue as a charity in Scotland. The Club holds two one-day meetings each year, in spring and autumn. The venue of the spring meeting is rotated between different towns, including Dunoon, Oban. LochgilpheadandTarbert.Thc autumn meeting and AGM are usually held in Invenny or another conveniently central location. The Club organises field trips for members. It also publishes the annual Argyll Bird Report and a quarterly members’ newsletter, The Eider, which includes details of club activities, reports from meetings and field trips, and feature articles by members and others, Each year the subscription entitles you to the ArgyZl Bird Report, four issues of The Eider, and free admission to the two annual meetings. There are four kinds of membership: current rates (at 1 October 1999) are: Ordinary E10; Junior (under 17) E3; Family €15; Corporate E25 Subscriptions (by cheque or standing order) are due on 1 January. Anyonejoining after 1 Octoberis covered until the end of the following year. -

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013

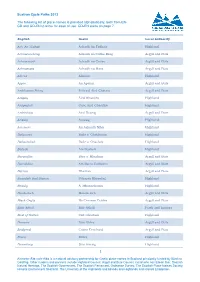

Sustran Cycle Paths 2013 The following list of place-names is provided alphabetically, both from EN- GD and GD-EN to allow for ease of use. GD-EN starts on page 7. English Gaelic Local Authority Ach' An Todhair Achadh An Todhair Highland Achnacreebeag Achadh na Crithe Beag Argyll and Bute Achnacroish Achadh na Croise Argyll and Bute Achnamara Achadh na Mara Argyll and Bute Alness Alanais Highland Appin An Apainn Argyll and Bute Ardchattan Priory Priòraid Àird Chatain Argyll and Bute Ardgay Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardgayhill Cnoc Àird Ghaoithe Highland Ardrishaig Àird Driseig Argyll and Bute Arisaig Àrasaig Highland Aviemore An Aghaidh Mhòr Highland Balgowan Baile a' Ghobhainn Highland Ballachulish Baile a' Chaolais Highland Balloch Am Bealach Highland Baravullin Bàrr a' Mhuilinn Argyll and Bute Barcaldine Am Barra Calltainn Argyll and Bute Barran Bharran Argyll and Bute Beasdale Rail Station Stèisean Bhiasdail Highland Beauly A' Mhanachainn Highland Benderloch Meadarloch Argyll and Bute Black Crofts Na Croitean Dubha Argyll and Bute Blair Atholl Blàr Athall Perth and kinross Boat of Garten Coit Ghartain Highland Bonawe Bun Obha Argyll and Bute Bridgend Ceann Drochaid Argyll and Bute Brora Brùra Highland Bunarkaig Bun Airceig Highland 1 Ainmean-Àite na h-Alba is a national advisory partnership for Gaelic place-names in Scotland principally funded by Bòrd na Gaidhlig. Other funders and partners include Highland Council, Argyll and Bute Council, Comhairle nan Eilean Siar, Scottish Natural Heritage, The Scottish Government, The Scottish Parliament, Ordnance Survey, The Scottish Place-Names Society, Historic Environment Scotland, The University of the Highlands and Islands and Highlands and Islands Enterprise.