Loss of Color Terms Not Demonstrated Supporting Details for Letter to Appear in PNAS Accepted 22 August 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kurtjar Placenames PAUL BLACK

CHAPTER 19 Kurtjar placenames PAUL BLACK Introduction This is a study of placenames recorded during research on the Kurtjar language of south-western Cape York Peninsula in the late 1970s. After introducing the language and its speakers’ knowledge of placenames (see below), the paper discusses those names for which etymologies can be proposed, including ones which are homophonous to common nouns (see ‘Names from common nouns’) as well as those formed by compounding and/or affixation (see under headings ‘Names formed as compounds’ to ‘Descriptive clauses’). Especially numerous are ones involving the many allomorphs of the locative suffix, including one found only fossilised in placenames (see ‘Names formed with a locative suffix’). Descriptive clauses used to designate a few sites are also discussed, whether or not they represent proper names (see ‘Descriptive clauses’). The nature of the names is quite similar to that in nearby languages, as will be illustrated by the occasional citation of names from Koko-Bera, to the north, although the unusual phonological development of Kurtjar poses special problems for the analysis of some names (see ‘Notes on phonology and transcription’). The language and the data The traditional territory of the Kurtjar is in south-western Cape York Peninsula, along the Gulf of Carpentaria coast from near the Staaten River to south of the Smithburn River; the accompanying map (Figure 19.1) is a modified version of one in a manuscript by Black and Gilbert (1996). The data discussed here was gathered during a general study of the Kurtjar language between 1974 and 1979. At this time it seemed that the language was no longer in general use, although there were still about a dozen people, mostly elderly, who could speak it with some fluency. -

Computational Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Pama-Nyungan Verb Conjugation Classes

Abstract Computational Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Pama-Nyungan Verb Conjugation Classes Parker Lorber Brody 2020 The Pama-Nyungan language family comprises some 300 Indigenous languages, span- ning the majority of the Australian continent. The varied verb conjugation class systems of the modern Pama-Nyungan languages have been the object of contin- ued interest among researchers seeking to understand how these systems may have changed over time and to reconstruct the verb conjugation class system of the com- mon ancestor of Pama-Nyungan. This dissertation offers a new approach to this task, namely the application of Bayesian phylogenetic reconstruction models, which are employed in both testing existing hypotheses and proposing new trajectories for the change over time of the organization of the verbal lexicon into inflection classes. Data from 111 Pama-Nyungan languages was collected based on features of the verb conjugation class systems, including the number of distinct inflectional patterns and how conjugation class membership is determined. Results favor reconstructing a re- stricted set of conjugation classes in the prehistory of Pama-Nyungan. Moreover, I show evidence that the evolution of different parts of the conjugation class sytem are highly correlated. The dissertation concludes with an excursus into the utility of closed-class morphological data in resolving areas of uncertainty in the continuing stochastic reconstruction of the internal structure of Pama-Nyungan. Computational Phylogenetic Reconstruction of Pama-Nyungan Verb Conjugation Classes A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Yale University in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Parker Lorber Brody Dissertation Director: Dr. Claire Bowern December 2020 Copyright c 2020 by Parker Lorber Brody All rights reserved. -

Salvage Studies of Western Queensland Aboriginallanguages

PACIFIC LINGUISTICS Series B-1 05 SALVAGE STUDIES OF WESTERN QUEENSLAND ABORIGINALLANGUAGES Gavan Breen Department of Linguistics Research School of Pacific Studies THE AUSTRALIAN NATIONAL UNIVERSITY Breen, G. Salvage studies of a number of extinct Aboriginal languages of Western Queensland. B-105, xii + 177 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 1990. DOI:10.15144/PL-B105.cover ©1990 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. PACIFIC LINGUISTICS is issued through the Linguistic Circle of Canberra and consists of four series: SERIES A: Occasional Papers SERIES C: Books SERIES B: Monographs SERIES D: Special Publications FOUNDING EDITOR: S.A. Wurrn EDITORIAL BOARD: K.A. Adelaar, T.E. Dutton, A.K. Pawley, M.D. Ross, D.T. Tryon EDITORIAL ADVISERS: BW. Be nder K.A. McElha no n Univers ity ofHa waii Summer Institute of Linguis tics David Bra dle y H. P. McKaughan La Trobe Univers ity Unive rsityof Hawaii Mi chael G.Cl yne P. Miihlhll usler Mo nash Univers ity Bond Univers ity S.H. Elbert G.N. O' Grady Uni ve rs ity ofHa waii Univers ity of Victoria, B.C. KJ. Frank li n K. L. Pike SummerIn stitute ofLingui s tics SummerIn s titute of Linguis tics W.W. Glove r E. C. Po lo me SummerIn stit ute of Linguis tics Unive rsity ofTe xas G.W. Grace Gillian Sa nkoff University ofHa wa ii Universityof Pe nns ylvania M.A.K. Halliday W.A. L. -

Speaking Kunjen: an Ethnography of Oykangand Kinship and Communication

Speaking Kunjen: an ethnography of Oykangand kinship and communication Pacific Linguistics 582 Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board. FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: John Bowden, Malcolm Ross and Darrell Tryon (Managing Editors), I Wayan Arka, David Nash, Andrew Pawley, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Karen Adams, Arizona State University Lillian Huang, National Taiwan Normal Alexander Adelaar, University of Melbourne University Peter Austin, School of Oriental and African Bambang Kaswanti Purwo, Universitas Atma Studies Jaya Byron Bender, University of Hawai‘i Marian Klamer, Universiteit Leiden Walter Bisang, Johannes Gutenberg- Harold Koch, The Australian National Universität Mainz University Robert Blust, University of Hawai‘i Frantisek Lichtenberk, University of David Bradley, La Trobe University Auckland Lyle Campbell, University of Utah John Lynch, University of the South Pacific James Collins, Universiti Kebangsaan Patrick McConvell, Australian Institute of Malaysia Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Bernard Comrie, Max Planck Institute for Studies Evolutionary Anthropology William McGregor, Aarhus Universitet Soenjono Dardjowidjojo, Universitas Atma Ulrike Mosel, Christian-Albrechts- Jaya Universität zu Kiel Matthew Dryer, State University of New York Claire Moyse-Faurie, Centre National de la at Buffalo Recherche Scientifique Jerold A. -

Talk About Jan 2021

Talk-About The official newsletter for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Health Leadership Team January 2021 Cadetship Program preparing our future Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander workforce A collaboration between the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Leadership Team (A&TSILT), Metro North Allied Health and the Metro North Office of the Chief Executive has seen an Indigenous Cadetship Program successfully rolled out across Metro North. Continued page 5 > Give us Contact information feedback Royal Brisbane and Women’s Hospital We welcome your feedback, Indigenous Hospital Liaison Officer Ph: 3646 4154 / 0408 472 385 contributions, story ideas and details on any upcoming events. Please After hours Ph: 3646 5106 / 0408 472 385 contact Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Leadership Team at A_TSIHU_ The Prince Charles Hospital [email protected] or phone Indigenous Hospital Liaison Officer Ph: 3139 5165 / 0436 690 306 (07) 3139 3231. After Hours Ph: 3139 6429 / 0429 897 982 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Leadership Team Redcliffe Hospital If you have any feedback regarding the Indigenous Hospital Liaison Officer Ph: 3049 6791 Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Leadership Team services, programs and After Hours Ph: 3049 9734 initiatives, you can contact the following: Caboolture/Kilcoy Hospital Mail to: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Indigenous Hospital Liaison Officer Ph: 5433 8249 Leadership Team, Building 26, Chermside After Hours Ph: 5316 5481 Community Health Centre, 490 Hamilton Road, Chermside QLD 4032. Community Indigenous Primary Health Team Email to: Manager Ph: 3360 4758 / 0419 856 253 [email protected] Alternatively, call and ask for our Safety Indigenous Sexual Health Team and Quality Officer on 3647 9531. -

Arthur Capell Papers MS 4577 Finding Aid Prepared by J.E

Arthur Capell papers MS 4577 Finding aid prepared by J.E. Churches, additional material added by C. Zdanowicz This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit May 04, 2016 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library March 2010 1 Lawson Crescent Acton Peninsula Acton Canberra, ACT, 2600 +61 2 6246 1111 [email protected] Arthur Capell papers MS 4577 Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................. 4 Biographical note ........................................................................................................................................... 6 Scope and Contents note ............................................................................................................................... 6 Arrangement note .......................................................................................................................................... 7 Administrative Information ......................................................................................................................... 8 Related Materials ......................................................................................................................................... 8 Controlled Access Headings ......................................................................................................................... 9 Physical Characteristics -

Phonotactics in Historical Linguistics: Quantitative Interrogation of a Novel Data Source

Phonotactics in historical linguistics: Quantitative interrogation of a novel data source Jayden Macklin-Cordes BA (Hons) 0000-0003-1910-3969 A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2021 School of Languages and Cultures Abstract Historical linguistics has been uncovering historical patterns of shared linguistic descent with consid- erable success for nearly two centuries. In recent decades, historical linguistics has been augmented with quantitative phylogenetic methods, increasing the scope and scale of linguistic phylogenetic trees that can be inferred and, by extension, the kinds of historical questions that can be investigated. Throughout this period of rapid methodological development, lexical cognate data has remained the main currency of interest. However, there is an immense array of structural variation throughout the world’s languages—the outcome of thousands of years of linguistic evolution—raising the prospect of additional sources of historical signal which could help infer shared linguistic pasts. This thesis investigates the prospect of making linguistic phylogenetic inferences using quantitative phonotactic data, semi-automatically extracted from wordlists. The primary research question moti- vating the study is as follows. Can a linguistic phylogeny be inferred with greater confidence when lexical cognate data is combined with phonotactic data? Underlying this is the more general question of how to approach and evaluate novel empirical data sources in linguistic phylogenetic research. I begin with a literature review, situating current linguistic phylogenetic research within historical linguistics broadly and elucidating the motivations for looking further into phonotactics as a data source. I also introduce Australian languages and their phonological profiles, as these provide the language sample for the rest of the thesis. -

Guide to Sound Recordings Collected by Ken Hale, 1958-1960

Finding aid HALE_K06 Sound recordings collected by Ken Hale, 1958-1960 Prepared November 2014 by SL Last updated 8 December 2017 ACCESS Availability of copies Listening copies are available. Contact the AIATSIS Audiovisual Access Unit by completing an online enquiry form or phone (02) 6261 4212 to arrange an appointment to listen to the recordings or to order copies. Restrictions on listening This collection is open for listening. Restrictions on use Copies of this collection may be made for private research. Permission must be sought from the relevant Indigenous individual, family or community for any publication or quotation of this material. Any publication or quotation must be consistent with the Copyright Act (1968). SCOPE AND CONTENT NOTE Date: 1958-1960 Extent: 124 audiotape reels ; 5 in. 2 audiotape reels ; 10 1/2 in. Production history These recordings were collected 1958 1nd 1960 by linguist Ken Hale during fieldwork in Gunbalanya, NT, Borroloola, NT, Gurungu, NT, Brunette Downs, NT, Anthony Lagoon, NT, Alice Springs, NT, Oodnadatta, SA, Papunya, NT, Roebourne, WA, Areyonga, NT, Yuendumu, NT, Warrabri, NT, Bidyadanga, WA, Nicholson, WA, Wave Hill, NT, Tennant Creek, NT, Barrow Creek, NT, Murray Downs, NT, Hermannsburg, NT, Santa Teresa, NT, Bond Springs, NT, Port Augusta, NT, Dajarra, Qld, Woree, Qld, Cooktown, Qld, Mitchell River, Qld, Yarrabah, Qld, Holroyd, Qld, Aurukun, Qld, Portland Roads, Qld, Weipa, Qld and Normanton, Qld. The purpose of the field trips was to document the languages and occasionally songs of Indigenous peoples of these areas. The language groups of the speakers and performers are indicated in parentheses after their names. -

J Gavan Breen

AIATSIS Collections Catalogue Finding Aid index Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies Library Language collections deposited at AIATSIS by J Gavan Breen 1967-1979 CONTENTS COLLECTION SUMMARY 3 CULTURAL SENSITIVITY STATEMENT 4 ACCESS TO COLLECTION 4 COLLECTION OVERVIEW 5 BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE 8 SERIES DESCRIPTION 9 Series 1 C12 Antekerrepenhe 9 Series 2 G12.1 Bularnu 11 Series 3 N155 Garrwa and G23 Waanyi 12 Series 4 D30 Kullilli 13 Series 5 G8 Yalarnnga 13 Series 6 G13 Kalkatungu and G16 Mayi-Thakurti/Mitakoodi 14 Series 7 G49: Kok Narr 15 Series 8 L38 Kungkari and L36 Pirriya 15 Composite Finding Aid: Language collections; Gavan Breen Series 9 G31 Gkuthaarn and G28 Kukatj 16 Series 10 D42 Margany and D43 Gunya 17 Series 11 D33 Kooma/Gwamu 18 Series 12 E39 Wadjigu 18 Series 13 E32 Gooreng Gooreng 18 Series 14 E60 Gudjal 19 Series 15 E40 Gangulu 19 Series 16 E56 Biri 19 Series 17 D31 Budjari/Badjiri 19 Series 18 D37 Gunggari 20 Series 19 D44 Mandandanji 20 Series 20 G21 Mbara and Y131 Yanga 20 Series 21 L34 Mithaka 21 Series 22 G17 Ngawun 21 Series 23 G6 Pitta Pitta 22 Series 24 C16 Wakaya 23 Series 25 L25 Wangkumara and L26 Punthamara 24 Series 26 G10 Warluwarra 25 Series 27 L18 Yandruwandha 25 Series 28 L23 Yawarrawarrka 26 Series 29 L22 Ngamini 27 Series 30 Reports to AIAS on Field Trips 27 Annex A A "Never say die: Gavan Breen’s life of service to the documentation of Australian Indigenous languages” 29 Annex B Gavan Breen Language Collections Without Finding Aids 50 2 Composite Finding Aid: Language collections; -

National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005 National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005

National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005 National Indigenous Languages Survey Report 2005 Report submitted to the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts by the Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies in association with the Federation of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages Front cover photo: Yipirinya School Choir, Northern Territory. Photo by Faith Baisden Disclaimer The Commonwealth, its employees, officers and agents are not responsible for the activities of organisations and agencies listed in this report and do not accept any liability for the results of any action taken in reliance upon, or based on or in connection with this report. To the extent legally possible, the Commonwealth, its employees, officers and agents, disclaim all liability arising by reason of any breach of any duty in tort (including negligence and negligent misstatement) or as a result of any errors and omissions contained in this document. The views expressed in this report and organisations and agencies listed do not have the endorsement of the Department of Communications, Information Technology and the Arts (DCITA). ISBN 0 642753 229 © Commonwealth of Australia 2005 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the Commonwealth. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the: Commonwealth Copyright Administration Attorney-General’s Department Robert Garran Offices National Circuit CANBERRA ACT 2600 Or visit http://www.ag.gov.au/cca This report was commissioned by the former Broadcasting, Languages and Arts and Culture Branch of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Services (ATSIS). -

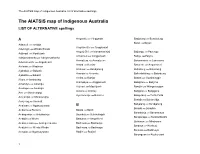

The AIATSIS Map of Indigenous Australia, List of Alternative Spellings

The AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia, list of alternative spellings The AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia LIST OF ALTERNATIVE spellings A Angardie see Yinggarda Badjulung see Bundjalung Baiali see Bayali Adawuli see Iwaidja Angkamuthi see Anggamudi Adetingiti see Winda Winda Angutj Giri see Marramaninjsji Baijungu see Payungu Adjinadi see Mpalitjanh Ankamuti see Anggamudi Bailgu see Palyku Adnjamathanha see Adnyamathanha Anmatjera see Anmatyerre Bakanambia see Lamalama Adumakwithi see Anguthimri Araba see Kurtjar Bakwithi see Anguthimri Airiman see Wagiman Arakwal see Bundjalung Balladong see Balardung Ajabakan see Bakanh Aranda see Arrernte Ballerdokking see Balardung Ajabatha see Bakanh Areba see Kurtjar Banbai see Gumbainggir Alura see Jaminjung Atampaya see Anggamudi Bandjima see Banjima Amandyo see Amangu Atjinuri see Mpalitjanh Bandjin see Wargamaygan Amangoo see Amangu Awara see Warray Bangalla see Banggarla Ami see Maranunggu Ayerrerenge see Bularnu Bangerang see Yorta Yorta Amijangal see Maranunggu Banidja see Bukurnidja Amurrag see Amarak Banjalang see Bundjalung Anaiwan see Nganyaywana B Barada see Baradha Anbarra see Burarra Baada see Bardi Baranbinja see Barranbinya Andagirinja see Antakarinja Baanbay see Gumbainggir Baraparapa see Baraba Baraba Andajin see Worla Baatjana see Anguthimri Barbaram see Mbabaram Andakerebina see Andegerebenha Badimaia see Badimaya Bardaya see Konbudj Andyinit see Winda Winda Badimara see Badimaya Barmaia see Badimaya Anewan see Nganyaywana Badjiri see Budjari Barunguan see Kuuku-yani 1 The -

AIATSIS Lan Ngua Ge T Hesaurus

AIATSIS Language Thesauurus November 2017 About AIATSIS – www.aiatsis.gov.au The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) is the world’s leading research, collecting and publishing organisation in Australian Indigenous studies. We are a network of council and committees, members, staff and other stakeholders working in partnership with Indigenous Australians to carry out activities that acknowledge, affirm and raise awareness of Australian Indigenous cultures and histories, in all their richness and diversity. AIATSIS develops, maintains and preserves well documented archives and collections and by maximising access to these, particularly by Indigenous peoples, in keeping with appropriate cultural and ethical practices. AIATSIS Thesaurus - Copyright Statement "This work is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only (retaining this notice) for your personal, non-commercial use within your organisation. All other rights are reserved. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to The Library Director, The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies, GPO Box 553, Canberra ACT 2601." AIATSIS Language Thesaurus Introduction The AIATSIS thesauri have been made available to assist libraries, keeping places and Indigenous knowledge centres in indexing / cataloguing their collections using the most appropriate terms. This is also in accord with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Library and Information Research Network (ATSILIRN) Protocols - http://aiatsis.gov.au/atsilirn/protocols.php Protocol 4.1 states: “Develop, implement and use a national thesaurus for describing documentation relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and issues” We trust that the AIATSIS Thesauri will serve to assist in this task.