War, Chronology, and Causality in the Titicaca Basin

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Quispe Pacco Sandro.Pdf

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN SECUNDARIA COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE MAUKA LLACTA DEL DISTRITO DE NUÑOA TESIS PRESENTADA POR: SANDRO QUISPE PACCO PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO DE LICENCIADO EN EDUCACIÓN CON MENCIÓN EN LA ESPECIALIDAD DE CIENCIAS SOCIALES PROMOCIÓN 2016- II PUNO- PERÚ 2017 1 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA EDUCACIÓN ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE EDUCACIÓN SEUNDARIA COMPLEJO ARQUEOLÓGICO DE MAUKA LLACTA DEL D ���.r NUÑOA SANDRO QUISPE PACCO APROBADA POR EL SIGUIENTE JURADO: PRESIDENTE e;- • -- PRIMER MIEMBRO --------------------- > '" ... _:J&ª··--·--••__--s;; E • Dr. Jorge Alfredo Ortiz Del Carpio SEGUNDO MIEMBRO --------M--.-S--c--. --R--e-b-�eca Alano�ca G�u�tiérre-z-- -----�--- f DIRECTOR ASESOR ------------------ , M.Sc. Lor-- �VÍlmore Lovón -L-o--v-ó--n-- ------------- Área: Disciplinas Científicas Tema: Patrimonio Histórico Cultural DEDICATORIA Dedico este informe de investigación a Dios, a mi madre por su apoyo incondicional, durante estos años de estudio en el nivel pregrado en la UNA - Puno. Para todos con los que comparto el día a día, a ellos hago la dedicatoria. 2 AGRADECIMIENTO Mi principal agradecimiento a la Universidad Nacional del Altiplano – Puno primera casa superior de estudios de la región de Puno. A la Facultad de Educación, en especial a los docentes de la especialidad de Ciencias Sociales, que han sido parte de nuestro crecimiento personal y profesional. A mi familia por haberme apoyado económica y moralmente en -

Bulletin De L'institut Français D'études Andines 34 (1) | 2005

Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines 34 (1) | 2005 Varia Edición electrónica URL: http://journals.openedition.org/bifea/5562 DOI: 10.4000/bifea.5562 ISSN: 2076-5827 Editor Institut Français d'Études Andines Edición impresa Fecha de publicación: 1 mayo 2005 ISSN: 0303-7495 Referencia electrónica Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines, 34 (1) | 2005 [En línea], Publicado el 08 mayo 2005, consultado el 08 diciembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/bifea/5562 ; DOI : https:// doi.org/10.4000/bifea.5562 Les contenus du Bulletin de l’Institut français d’études andines sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Olivier Dollfus, una pasión por los Andes Bulletin de l’Institut Français d’Études Andines / 2005, 34 (1): 1-4 IFEA Olivier Dollfus, una pasión por los Andes Évelyne Mesclier* Henri Godard** Jean-Paul Deler*** En la sabiduría aymara, el pasado está por delante de nosotros y podemos verlo alejarse, mientras que el futuro está detrás nuestro, invisible e irreversible; Olivier Dollfus apreciaba esta metáfora del hilo de la vida y del curso de la historia. En el 2004, marcado por las secuelas físicas de un grave accidente de salud pero mentalmente alerta, realizó su más caro sueño desde hacía varios años: regresar al Perú, que iba a ser su último gran viaje. En 1957, el joven de 26 años que no hablaba castellano, aterrizó en Lima por vez primera, luego de un largo sobrevuelo sobre América del Sur con un magnífico clima, atravesando la Amazonía y los Andes —de los que se enamoró inmediatamente— hasta el desierto costero del Pacífico. -

DE HUAMANGA LOS PUEBLOS DE LA Cuenea DE QARACHA

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DE SAN CRISTÓBAL · DE HUAMANGA Facultad de Ciencias Sociales Escue!i~fde Formación Profesional de Arqueología e Historia LOS PUEBLOS DE LA CUENeA DE QARACHA (XV-XVII) Tesis para optar el título profesional de Licenciado en Historia Presentado por: DAVID QUICHUA CHAICO Asesor: JEFREY GAMARRA CARRILLO Ayacucho, Diciembre de 2013 Para Zósima Chaico, mi madre; e Isaac T. Quispe mi compañero. Recordados en su ausencia , ·.C~ :4>\ ~ 'Ct. •a... 1 ,;;; .'; .t.H~p&ntina. 2 ÍNDICE INTRODUCCIÓN 10 CAPfTULO 1 GEOGRAFÍA Y PUEBLOS PREHISPÁNICOS DE LA CUENCA DE QARACHA 1.1 Geografía de la cuenca de Qaracha 14 1.2. Curacazgo de la cuenca de Qaracha antes del dominio Inca 16 1.3. La incorporación de la cuenca de Qaracha y el control del Estado Inca 20 CAPITUL02 LAS ENCOMIENDAS EN LA CUENCA DE QARACHA 2.1. La encomienda indiana 30 2.2. Las encomiendas de la cuenca de Qaracha 32 CAPÍTUL03 LAS REDUCCIONES EN LA CUENCA DE QARACHA Y EL SURGIMIENTO DEL PUEBLO DE SACSAMARCA Y TAULLI 3.1. Los fundamentos de la reducción española 40 3.2. LA REDUCCIÓN DE SACSAMARCA 45 3.2.1. La delimitación territorial de Sac.samarca y sus reconocimientos 47 3.3. LA REDUCCIÓN DEL PUEBLO DE SAN JERÓNIMO DE TAULLI 50 3.3.1. El surgimiento del pueblo de Taulli 50 3.3.2. Sus posesiones territoriales 51 3.3.3. Economfa y autoridades del pueblo de Taulli 53 3.3.4. Taulli y sus conflictos territoriales con los pueblos vecinos 54 CAPITUL04 SURGIK~IENTO DEL PUEBLO DE SARHUA y SANCOS 4.1. -

Conocimiento Local Cultivo De La Papa

Publicación realizada en conmemoración al Año Internacional de la Papa - 2008 Freddy Canqui Eddy Morales Instituciones Financiadoras Conocimiento Local Instituciones Responsables en el Cultivo de la Papa Presentación El cultivo de la papa es una actividad milenaria que ha sido, es y seguirá siendo, parte fundamental de la vida de las comunidades andinas. Haciendo un recorrido por la región del Altiplano Norte, el libro de Freddy Canqui y Eddy Morales se acerca a la cadena productiva de la papa a través de la vivencia cotidiana de 10 familias productoras de este milenario tubérculo. Es importante reconocer que el cultivo de la papa está íntimamente sujeto a la cosmovisión andina y a lo sagrado, haciendo parte relevante la relación del ser humano con su tierra y su comunidad. El libro revela el conocimiento local que mujeres y hombres del Altiplano Norte fueron construyendo año tras año, siendo éste transmitido de generación en generación. “Conocimiento Local en el Cultivo de la Papa” es un libro de gran aporte al presentar panoramas de la vida de productores, mostrando la estructura, roles y funciones de los miembros de las familias alrededor del cultivo de la papa. El libro visibiliza la gran importancia de los saberes locales y del apoyo de instituciones ligadas al desarrollo para el progreso de sus comunidades, ello a través de la implementación de tecnologías que mejoran los sistemas de producción en torno al cultivo de la papa. Por todo lo descrito, la Embajada Real de Dinamarca (DANIDA) y la Agencia Suiza para el Desarrollo y la Cooperación (COSUDE) se sienten complacidos por contribuir a tan interesante documento. -

Searching for the 'True Process of Change'

Searching for the ‘True Process of Change’ Consent and Discord Among Indigenous Peasant Movements in Northern Potosí, Bolivia Monika Hess, Sabino Ruiz Flores NCCR North-South Dialogue, no. 50 2014 dialogue The present study was carried out at the following partner institutions of the NCCR North-South: Postgrado en Ciencias del Desarrollo (CIDES), Universidad mayor de San Andrés (UMSA), La Paz, Bolivia Development Study Group Department of Geography University of Zurich The NCCR North-South (Research Partnerships for Mitigating Syndromes of Global Change) is one of 27 National Centres of Competence in Research established by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF). It is implemented by the SNSF and co- funded by the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC), and the participating institutions in Switzerland. The NCCR North-South carries out disciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary research on issues relating to sustainable development in developing and transition countries as well as in Switzerland. http://www.north-south.unibe.ch Searching for the ‘True Process of Change’ Consent and Discord Among Indigenous Peasant Movements in Northern Potosí, Bolivia Monika Hess, Sabino Ruiz Flores NCCR North-South Dialogue, no. 50 2014 Citation Hess M, Ruiz Flores S. 2014. Searching for the ‘True Process of Change’: Consent and Discord Among Indigenous Peasant Move- ments in Northern Potosí, Bolivia. NCCR North-South Dialogue 50 (Working Paper, Research Project 1 – Contested Rural Development). Bern and Zurich, Switzerland: NCCR North-South. A Working Paper for the Research Project on: “Contested Rural Development – new perspectives on ‘non-state actors and movements’ and the politics of livelihood-centered policies”, coordi- nated by Urs Geiser and R. -

Línea Base De Conocimientos Sobre Los Recursos Hidrológicos E Hidrobiológicos En El Sistema TDPS Con Enfoque En La Cuenca Del Lago Titicaca ©Roberthofstede

Línea base de conocimientos sobre los recursos hidrológicos e hidrobiológicos en el sistema TDPS con enfoque en la cuenca del Lago Titicaca ©RobertHofstede Oficina Regional para América del Sur La designación de entidades geográficas y la presentación del material en esta publicación no implican la expresión de ninguna opinión por parte de la UICN respecto a la condición jurídica de ningún país, territorio o área, o de sus autoridades, o referente a la delimitación de sus fronteras y límites. Los puntos de vista que se expresan en esta publicación no reflejan necesariamente los de la UICN. Publicado por: UICN, Quito, Ecuador IRD Institut de Recherche pour Le Développement. Derechos reservados: © 2014 Unión Internacional para la Conservación de la Naturaleza y de los Recursos Naturales. Se autoriza la reproducción de esta publicación con fines educativos y otros fines no comerciales sin permiso escrito previo de parte de quien detenta los derechos de autor con tal de que se mencione la fuente. Se prohíbe reproducir esta publicación para venderla o para otros fines comerciales sin permiso escrito previo de quien detenta los derechos de autor. Con el auspicio de: Con la colaboración de: UMSA – Universidad UMSS – Universidad Mayor de San André Mayor de San Simón, La Paz, Bolivia Cochabamba, Bolivia Citación: M. Pouilly; X. Lazzaro; D. Point; M. Aguirre (2014). Línea base de conocimientos sobre los recursos hidrológicos en el sistema TDPS con enfoque en la cuenca del Lago Titicaca. IRD - UICN, Quito, Ecuador. 320 pp. Revisión: Philippe Vauchel (IRD), Bernard Francou (IRD), Jorge Molina (UMSA), François Marie Gibon (IRD). Editores: UICN–Mario Aguirre; IRD–Marc Pouilly, Xavier Lazzaro & DavidPoint Portada: Robert Hosfstede Impresión: Talleres Gráficos PÉREZ , [email protected] Depósito Legal: nº 4‐1-196-14PO, La Paz, Bolivia ISBN: nº978‐99974-41-84-3 Disponible en: www.uicn.org/sur Recursos hidrológicos e hidrobiológicos del sistema TDPS Prólogo Trabajando por el Lago Más… El lago Titicaca es único en el mundo. -

Community Formation and the Emergence of the Inca

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2019 Assembling States: Community Formation And The meE rgence Of The ncI a Empire Thomas John Hardy University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Art, Architecture, and Archaeology Commons Recommended Citation Hardy, Thomas John, "Assembling States: Community Formation And The meE rgence Of The ncaI Empire" (2019). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3245. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3245 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3245 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Assembling States: Community Formation And The meE rgence Of The Inca Empire Abstract This dissertation investigates the processes through which the Inca state emerged in the south-central Andes, ca. 1400 CE in Cusco, Peru, an area that was to become the political center of the largest indigenous empire in the Western hemisphere. Many approaches to this topic over the past several decades have framed state formation in a social evolutionary framework, a perspective that has come under increasing critique in recent years. I argue that theoretical attempts to overcome these problems have been ultimately confounded, and in order to resolve these contradictions, an ontological shift is needed. I adopt a relational perspective towards approaching the emergence of the Inca state – in particular, that of assemblage theory. Treating states and other complex social entities as assemblages means understanding them as open-ended and historically individuated phenomena, emerging from centuries or millennia of sociopolitical, cultural, and material engagements with the human and non-human world, and constituted over the longue durée. -

New Age Tourism and Evangelicalism in the 'Last

NEGOTIATING EVANGELICALISM AND NEW AGE TOURISM THROUGH QUECHUA ONTOLOGIES IN CUZCO, PERU by Guillermo Salas Carreño A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Anthropology) in The University of Michigan 2012 Doctoral Committee: Professor Bruce Mannheim, Chair Professor Judith T. Irvine Professor Paul C. Johnson Professor Webb Keane Professor Marisol de la Cadena, University of California Davis © Guillermo Salas Carreño All rights reserved 2012 To Stéphanie ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This dissertation was able to arrive to its final shape thanks to the support of many throughout its development. First of all I would like to thank the people of the community of Hapu (Paucartambo, Cuzco) who allowed me to stay at their community, participate in their daily life and in their festivities. Many thanks also to those who showed notable patience as well as engagement with a visitor who asked strange and absurd questions in a far from perfect Quechua. Because of the University of Michigan’s Institutional Review Board’s regulations I find myself unable to fully disclose their names. Given their public position of authority that allows me to mention them directly, I deeply thank the directive board of the community through its then president Francisco Apasa and the vice president José Machacca. Beyond the authorities, I particularly want to thank my compadres don Luis and doña Martina, Fabian and Viviana, José and María, Tomas and Florencia, and Francisco and Epifania for the many hours spent in their homes and their fields, sharing their food and daily tasks, and for their kindness in guiding me in Hapu, allowing me to participate in their daily life and answering my many questions. -

El Gran Pago De Mulsina O El Arte De Mover Las Montañas

Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines 34 (2) | 2005 Varia El gran pago de Mulsina o el arte de mover las montañas Le grand rituel d’offrandes à Mulsina ou l’art de déplacer les montagnes The great ritual at Mulsina or the art of moving mountains Xavier Bellenger Edición electrónica URL: http://journals.openedition.org/bifea/5506 DOI: 10.4000/bifea.5506 ISSN: 2076-5827 Editor Institut Français d'Études Andines Edición impresa Fecha de publicación: 1 agosto 2005 Paginación: 235-249 ISSN: 0303-7495 Referencia electrónica Xavier Bellenger, « El gran pago de Mulsina o el arte de mover las montañas », Bulletin de l'Institut français d'études andines [En línea], 34 (2) | 2005, Publicado el 08 agosto 2005, consultado el 10 diciembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/bifea/5506 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/bifea. 5506 Les contenus du Bulletin de l’Institut français d’études andines sont mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. ElBulletin antiguo de gran l’Institut pago Français de Mulsina d’Études o el arte Andines de mover / 2005, las 34montañas (2): 235- 249 El gran pago de Mulsina o el arte de mover las montañas Xavier Bellenger* Resumen La aprehensión de la geografía, tal como es enfocada durante las prácticas rituales profilácticas realizadas en Taquile, pequeña isla peruana del lago Titicaca, aporta importantes datos sobre la disposición y la percepción del espacio sagrado por parte de los miembros de esta comunidad insular agraria de lengua quechua. -

Presentación De Powerpoint

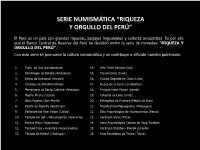

SERIE NUMISMÁTICA “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ” El Perú es un país con grandes riquezas, paisajes inigualables y culturas ancestrales. Es por ello que el Banco Central de Reserva del Perú ha decidido emitir la serie de monedas: “RIQUEZA Y ORGULLO DEL PERÚ”. Con esta serie se promueve la cultura numismática y se contribuye a difundir nuestro patrimonio. 1. Tumi de Oro (Lambayeque) 14. Arte Textil Paracas (Ica) 2. Sarcófagos de Karajía (Amazonas) 15. Tunanmarca (Junín) 3. Estela de Raimondi (Ancash) 16. Ciudad Sagrada de Caral (Lima) 4. Chullpas de Sillustani (Puno) 17. Huaca de la Luna (La Libertad) 5. Monasterio de Santa Catalina (Arequipa) 18. Antiguo Hotel Palace (Loreto) 6. Machu Picchu (Cusco) 19. Catedral de Lima (Lima) 7. Gran Pajatén (San Martín) 20. Petroglifos de Pusharo (Madre de Dios) 8. Piedra de Saywite (Apurimac) 21. Arquitectura Moqueguana (Moquegua) 9. Fortaleza del Real Felipe (Callao) 22. Sitio Arqueológico de Huarautambo (Pasco) 10. Templo del Sol – Vilcashuamán (Ayacucho) 23. Cerámica Vicús (Piura) 11. Kuntur Wasi (Cajamarca) 24. Zona Arqueológica Cabeza de Vaca Tumbes) 12. Templo Inca - Huaytará (Huancavelica) 25. Cerámica Shipibo – Konibo (Ucayali) 13. Templo de Kotosh (Huánuco) 26. Arco Parabólico de Tacna (Tacna) 1 TUMI DE ORO Especificaciones Técnicas En el reverso se aprecia en el centro el Tumi de Oro, instrumento de hoja corta, semilunar y empuñadura escultórica con la figura de ÑAYLAMP ícono mitológico de la Cultura Lambayeque. Al lado izquierdo del Tumi, la marca de la Casa Nacional de Moneda sobre un diseño geométrico de líneas verticales. Al lado derecho del Tumi, la denominación en números, el nombre de la unidad monetaria sobre unas líneas ondulantes, debajo la frase TUMI DE ORO, S. -

Lost Ancient Technology of Peru and Bolivia

Lost Ancient Technology Of Peru And Bolivia Copyright Brien Foerster 2012 All photos in this book as well as text other than that of the author are assumed to be copyright free; obtained from internet free file sharing sites. Dedication To those that came before us and left a legacy in stone that we are trying to comprehend. Although many archaeologists don’t like people outside of their field “digging into the past” so to speak when conventional explanations don’t satisfy, I feel it is essential. If the engineering feats of the Ancient Ones cannot or indeed are not answered satisfactorily, if the age of these stone works don’t include consultation from geologists, and if the oral traditions of those that are supposedly descendants of the master builders are not taken into account, then the full story is not present. One of the best examples of this regards the great Sphinx of Egypt, dated by most Egyptologists at about 4500 years. It took the insight and questioning mind of John Anthony West, veteran student of the history of that great land to invite a geologist to study the weathering patterns of the Sphinx and make an estimate of when and how such degradation took place. In stepped Dr. Robert Schoch, PhD at Boston University, who claimed, and still holds to the theory that such an effect was the result of rain, which could have only occurred prior to the time when the Pharaoh, the presumed builders, had existed. And it has taken the keen observations of an engineer, Christopher Dunn, to look at the Great Pyramid on the Giza Plateau and develop a very potent theory that it was indeed not the tomb of an egotistical Egyptian ruler, as in Khufu, but an electrical power plant that functioned on a grand scale thousands of years before Khufu (also known as Cheops) was born. -

Proyecto: Complejo Cultural Como Potenciador Turístico En El Centro Poblado De Uros Chulluni-Puno

UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO - PUNO FACULTAD DE INGENIERIA CIVIL Y ARQUITECTURA ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE ARQUITECTURA Y URBANISMO “PROYECTO: COMPLEJO CULTURAL COMO POTENCIADOR TURÍSTICO EN EL CENTRO POBLADO DE UROS CHULLUNI-PUNO” BORRADOR DE TESIS PRESENTADO POR: Bach. Arqto. Henry Franklin Torres Paredes Bach. Arqto. Luis Rodrigo Maquera Apaza PARA OPTAR EL TÍTULO PROFESIONAL DE: ARQUITECTO Y URBANISTA PUNO – PERÚ 2018 1 UNIVERSIDAD NACIONAL DEL ALTIPLANO - PUNO FACULTAD DE INGENIERIA CIVIL Y ARQUITECTURA ESCUELA PROFESIONAL DE ARQUITECTURA Y URBANISMO BORRADOR DE TESIS PROYECTO: COMPLEJO CULTURAL COMO POTENCIADOR TURÍSTICO EN EL CENTRO POBLADO DE UROS CHULLUNI-PUNO PRESENTADO POR: Bach. Arqto. Henry Franklin Torres Paredes Bach. Arqto. Luis Rodrigo Maquera Apaza PARA OPTAR EL TITULO PROFESIONAL DE: ARQUITECTO Y URBANISTA APROBADA POR: PRESIDENTE: ____________________________________ M.Sc. Sergio Javier Casapia Ochoa PRIMER MIEMBRO: ____________________________________ Arq. Yonny Walter Chávez Perea SEGUNDO MIEMBRO: ____________________________________ Arq. Vanessa Lucila Amachi Frisancho DIRECTOR / ASESOR: ____________________________________ M.Sc. Jorge Adan Villegas Abrill Área : PROYECTO URBANO Y AMBIENTE, ENTORNO CULTURAL Y PAISAJE Tema : COMPLEJO CULTURAL COMO POTENCIADOR TURÍSTICO EN EL CENTRO POBLADO DE UROS CHULLUNI 2 ÍNDICE GENERAL ÍNDICE GENERAL .............................................................................................................. 3 INDICE DE ILUSTRACIONES .............................................................................................