Interactions with Humans Are Jointly Influenced by Life History Stage And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Initial Research Question • M

4/30/2008 Macaques Human-Macaque ► Old World monkey Interactions and Related ► Body size: Medium to Large bodied ► Omnivorous: fruit, leaves, invertebrates Effects on Macaque ► Arboreal/terrestrial ► Social groups of 20-50 of both sexes and all ages Behavior and Conservation ► Alpha males usually fission to start own groups ► Native to Asia and Africa Denae Crowl ► Order = Primates ► Family = Cercopithecidae Department of ► Genus = Macaca Anthropology, SIUE Phyletic Species-Groups Within the Genus Macaca (A. F. Richard, et. al. 1989) 1. M. fascicularis group • M. cyclopic - Formosan rock, or Taiwan macaque • M. fascicularis - Crab-eating, or long-tailed macaque • M. fuscata - Japanese macaque • M. mulatta - Rhesus macaque 2. M. silenus-sylvanus group • M. nemestrina - Pigtail macaque • M. silenus - Lion-tailed macaque • M. sylvanus - Barbary macaque • M. brunnescens - Mana-Butung macaque Initial Research Question • M. hecki - Heck’s macaque • H. maura - Moor macaque • M. nigra - Celebes black macaque • M. nigrescens - Gorontalo macaque • M. ochreata - Booted macaque Human Perceptions vs. Macaque • M. tonkeana - Tonkean macaque 3. M. sinica group Behavior • M. assamensis - Assamese macaque • M. radiata - Bonnet macaque • M. sinica - Toque macaque • M. thibetana - Tibetan macaque 4. M. arctoides group • M. arctoides - Stumptail, or bear macaque Both human perceptions and macaques behaviors have been My Perception an issue due to the increasing amount of human-macaque interaction ► Bali, Indonesia ► Yap, Micronesian Island ►What is meant by ‘natural’ environment? ► . Revered . Pests What forms of conservation are beneficial to . Provisioned . Disease transmitters macaques and humans? . Welcomed tourist . Illegal transport to main ►What are the issues surrounding established attraction island conservation methods? . Illegal as pets . Crop-raiders 1 4/30/2008 Offerings in form of a flowers/fruits Methods = non-deliberate provisioning ►Reviewed published literature ►Variables . -

Chewing and Sucking Lice As Parasites of Iviammals and Birds

c.^,y ^r-^ 1 Ag84te DA Chewing and Sucking United States Lice as Parasites of Department of Agriculture IVIammals and Birds Agricultural Research Service Technical Bulletin Number 1849 July 1997 0 jc: United States Department of Agriculture Chewing and Sucking Agricultural Research Service Lice as Parasites of Technical Bulletin Number IVIammals and Birds 1849 July 1997 Manning A. Price and O.H. Graham U3DA, National Agrioultur«! Libmry NAL BIdg 10301 Baltimore Blvd Beltsvjlle, MD 20705-2351 Price (deceased) was professor of entomoiogy, Department of Ento- moiogy, Texas A&iVI University, College Station. Graham (retired) was research leader, USDA-ARS Screwworm Research Laboratory, Tuxtia Gutiérrez, Chiapas, Mexico. ABSTRACT Price, Manning A., and O.H. Graham. 1996. Chewing This publication reports research involving pesticides. It and Sucking Lice as Parasites of Mammals and Birds. does not recommend their use or imply that the uses U.S. Department of Agriculture, Technical Bulletin No. discussed here have been registered. All uses of pesti- 1849, 309 pp. cides must be registered by appropriate state or Federal agencies or both before they can be recommended. In all stages of their development, about 2,500 species of chewing lice are parasites of mammals or birds. While supplies last, single copies of this publication More than 500 species of blood-sucking lice attack may be obtained at no cost from Dr. O.H. Graham, only mammals. This publication emphasizes the most USDA-ARS, P.O. Box 969, Mission, TX 78572. Copies frequently seen genera and species of these lice, of this publication may be purchased from the National including geographic distribution, life history, habitats, Technical Information Service, 5285 Port Royal Road, ecology, host-parasite relationships, and economic Springfield, VA 22161. -

View / Open Gartland Oregon 0171A 12939.Pdf

MALE JAPANESE MACAQUE (MACACA FUSCATA) SOCIALITY: BEHAVIORAL STRATEGIES AND WELFARE SCIENCE APPLICATIONS by KYLEN NADINE GARTLAND A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Anthropology and the Graduate School of the University of Oregon in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2021 DISSERTATION APPROVAL PAGE Student: Kylen Nadine Gartland Title: Male Japanese Macaque (Macaca fuscata) Sociality: Behavioral Strategies and Welfare Science Applications This dissertation has been accepted and approved in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in the Department of Anthropology by: Frances White Chairperson Lawrence Ulibarri Core Member Steve Frost Core Member Renee Irvin Institutional Representative and Kate Mondlock Interim Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School Original approval signatures are on file with the University of Oregon Graduate School. Degree awarded March 2021 ii © 2021 Kylen Nadine Gartland iii DISSERTATION ABSTRACT Kylen Nadine Gartland Doctor of Philosophy Department of Anthropology February 2021 Title: Male Japanese macaque (Macaca fuscata) sociality: Behavioral strategies and welfare science application Evolutionarily, individuals should pursue social strategies which confer advantages such as coalitionary support, mating opportunities, or access to limited resources. How an individual forms and maintains social bonds may be influenced by a large number of factors including sex, age, dominance rank, group structure, group demographics, relatedness, or seasonality. Individuals may employ differential social strategies both in terms of the type and quantity of interactions they engage in as well as their chosen social partners. The objective of this dissertation is to examine sociality in adult male Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) and the varying strategies that individuals may employ depending on their relative position within a social group. -

1 Aazpa Librarians Special Interest Group

AAZPA LIBRARIANS SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP BIBLIOGRAPHY SERVICE The bibliography is provided as a service of the AAZPA LIBRARIANS SPECIAL INTEREST GROUP and THE CONSORTIUM OF AQUARIUMS, UNIVERSITIES AND ZOOS. TITLE: The Lion-tailed Macaque (Macaca silenus): An Indexed Bibliography AUTHOR & INSTITUTION: Gregg Thompson Woodland Park Zoological Gardens Seattle, Washington DATE: August, 1988 While the author of the following bibliography has attempted to make it as comprehensive as possible, it should not be considered as a complete listing of lion-tailed macaque references. In addition to the Primate Reference Library of the University of Washington Regional primate Center, most major bibliographic sources I have been utilized in the search for citations for inclusion in this bibliography. Despite such a search, it is inevitable that additional references exist. The author would appreciate receiving information regarding articles or publications that contain reference to lion-tailed macaques that are not listed in this bibliography. Except for the articles to which the author had direct access, the references have not been annotated. This bibliography will be updated on an annual basis and published as an addition to the yearly International Lion-tailed Macaque Studbook supplement. The author hopes that this bibliography will be of assistance to those working with or studying the lion-tailed macaque and welcomes comments or suggestions. Agoramoorthy, G. 1985. Non-human primates conservation in India. Animal Citizen, 22(4):31-33. [1] Albrecht, G.H. 1978. The craniofacial morphology of the Sulawesi macaques: Multivariate approaches to biological problems. Contributions to Primatology, 13:1. [2] Alciati G., M. Folin, P.P. Parnigotto, and G. -

日本モンキーセンター 霊長類和名リスト 2018年11月版 日本モンキーセンター霊長類和名編纂ワーキンググループ the Working Group on Japanese Nomenclature of Primate Species at Japan Monkey Centre

日本モンキーセンター 霊長類和名リスト 2018年11月版 日本モンキーセンター霊長類和名編纂ワーキンググループ The Working Group on Japanese Nomenclature of Primate Species at Japan Monkey Centre 種分類は原則としてIUCN Redlist (2017.12.5 Download)に従った.一部,必要と思われる種を補って計447種とした. また,近年の知見に照らして属を変更したものがある. 高次分類についてはIUCN/SSC Primate Specialist Group(www.primate-sg.org), Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Vol.3. Primates. (Mittermeier et.al. eds. 2013) , およびPrimate Adaptation & Evolution 3rd Ed. -

(12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8.236,308 B2 Kischel Et Al

USOO82363.08B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 8.236,308 B2 Kischel et al. (45) Date of Patent: Aug. 7, 2012 (54) COMPOSITION COMPRISING McLaughlin et al., Cancer Immunol. Immunother, 1999.48, 303 CROSS-SPECIES-SPECIFIC ANTIBODES 3.11. AND USES THEREOF The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, “Points to Consider in the Manufacture and Testing of Monoclonal (75) Inventors: Roman Kischel, Karlsfeld (DE); Tobias Antibody Products for Human Use.” pp. 1-50 Feb. 28, 1997.* Raum, München (DE); Bernd Hexham et al., Molecular Immunology 38 (2001) 397-408.* Schlereth, Germering (DE); Doris Rau, Gallart et al., Blood, vol.90, No. 4 Aug. 15, 1997: pp. 1576-1587.* Unterhaching (DE); Ronny Cierpka, Vajdos et al., J Mol Biol. Jul. 5, 2002:320(2):415-28.* München (DE); Peter Kufer, Moosburg Rudikoff et al., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 79: 1979-1983, Mar. (DE) 1982.* Colman P. M., Research in Immunology, 145:33-36, 1994.* (73) Assignee: Micromet AG, Munich (DE) International Search Report for PCT International Application No. PCT/EP2006/009782, mailed Nov. 7, 2007 (6 pgs.). *) Notice: Subject to anyy disclaimer, the term of this Bortoletto Nicola et al., “Optimizing Anti-CD3Affinity for Effective patent is extended or adjusted under 35 T Cell Targeting Against Tumor Cells'. European Journal of Immu U.S.C. 154(b) by 491 days. nology, Nov. 2002, vol. 32 (11), pp. 3102-3107. (XPO02436763). Fleiger, D. et al., “A Bispecific Single-Chain Antibody Directed Against EpCAM/CD3 in Combination with the Cytokines Interferon (21) Appl. -

Erin P. Riley, Ph.D

Erin P. Riley Professor of Anthropology Department of Anthropology San Diego State University San Diego, CA, USA 92182-6040 619.594.1150 (fax) [email protected] www.erinpriley.com EDUCATION 2005 Doctor of Philosophy, University of Georgia—Anthropology Dissertation: “Ethnoprimatology of Macaca tonkeana: The Interface of Primate Ecology, Human Ecology, and Conservation in Lore Lindu National Park, Sulawesi, Indonesia.” Dissertation committee: Dr. Carolyn L. Ehardt (chair), Dr. J. Peter Brosius, Dr. Dorothy M. Fragaszy, and Dr. Irwin S. Bernstein 2005 Graduate Certificate in Conservation Ecology and Sustainable Development, Institute of Ecology, University of Georgia 1995 Bachelor of Arts, Beloit College—Anthropology (Minor: Behavioral Studies) Phi Beta Kappa Scholar and graduated magna cum laude Advisor: Dr. Nancy Krusko PROFESSIONAL HISTORY 2016 – present Professor of Anthropology, San Diego State University 2012 Invited Visiting Professor, Roma Tre University, Rome, Italy 2010 – 2016 Associate Professor of Anthropology, San Diego State University 2006 – 2010 Assistant Professor of Anthropology, San Diego State University 2005 – 2006 Post-doctoral Research Fellow, Behavioral Biology Lab, Institute for Mind & Biology, University of Chicago; Advisor: Dr. Dario Maestripieri 2005 – 2006 Research Associate, Advancing Conservation in the Social Context Project, Department of Anthropology, University of Georgia 2004 – 2005 Research Associate, SANREM (Sustainable Agriculture and Natural Resource Management) Phase II, University of Georgia 2002, 2005 Lecturer of Anthropology, University of Georgia RILEY | April 2020, PAGE 2 RESEARCH EXPERIENCE 2017 – present Co-investigator. Entomological assessment of the last primate malaria foci to inform malaria elimination, Sabang, Pulau Wey, Indonesia (in collaboration with Dr. Isra Wahid (PI) and Dr. Janet Cox Singh (co-PI). 2016 – 2017 Principal Investigator. -

Diet Preferences and Habitat Use in Relation to Reproductive States in Females of a Wild Group of Macaca Maura Inhabiting Karaenta Forest, South Sulawesi

DIET PREFERENCES AND HABITAT USE IN RELATION TO REPRODUCTIVE STATES IN FEMALES OF A WILD GROUP OF MACACA MAURA INHABITING KARAENTA FOREST, SOUTH SULAWESI CRISTINA SAGNOTTI PASCASARJANA PROGRAM HASANUDDIN UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2012/2013 ii DIET PREFERENCES AND HABITAT USE IN RELATION TO REPRODUCTIVE STATES IN FEMALES OF A WILD GROUP OF MACACA MAURA INHABITING KARAENTA FOREST, SOUTH SULAWESI Thesis Required to Achieve Master Study Program Forestry Prepared and Submitted by CRISTINA SAGNOTTI To PASCASARJANA PROGRAM HASANUDDIN UNIVERSITY MAKASSAR 2012/2013 iii THESIS DIET PREFERENCES AND HABITAT USE IN RELATION TO REPRODUCTIVE STATES IN FEMALES OF A WILD GROUP OF MACACA MAURA INHABITING KARAENTA FOREST, SOUTH SULAWESI Prepared and Submitted by CRISTINA SAGNOTTI ID Number P3700211007 Approved by Advisory Committee _____________________________ ______________________________ Prof. Dr. Ir. Ngakan Putu Oka, M.Sc. Dr. Risma Illa Maulany, S.Hut, M.Sc Supervisor Senior Co-Supervisor ________________________ Dr. Monica Carosi, PhD Co-Supervisor iv THESIS STATEMENT OF AUTHENTICITY The undersigned Name: Cristina Sagnotti ID Number: P3700211007 Study Program: Forestry It states that the thesis I wrote is really a result of my own work, not an expropriation or the writing of other people. If later can be proven that most or the whole thesis is the results of other people's work, I am willing to accept sanctions for such actions. Makassar, Who Stated Cristina Sagnotti v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This research was part of the Dr. Monica Carosi’s research project “Ecology, costs & benefits of sexual swelling in Macaca maura ”, in cooperation with Tor Vergata University (Italy), Hasanuddin University and Bantimurung Bulusaraung National Park (Indonesia). Funding was provided by the Ministry of Education, University and Research of Italy. -

List of Taxa for Which MIL Has Images

LIST OF 27 ORDERS, 163 FAMILIES, 887 GENERA, AND 2064 SPECIES IN MAMMAL IMAGES LIBRARY 31 JULY 2021 AFROSORICIDA (9 genera, 12 species) CHRYSOCHLORIDAE - golden moles 1. Amblysomus hottentotus - Hottentot Golden Mole 2. Chrysospalax villosus - Rough-haired Golden Mole 3. Eremitalpa granti - Grant’s Golden Mole TENRECIDAE - tenrecs 1. Echinops telfairi - Lesser Hedgehog Tenrec 2. Hemicentetes semispinosus - Lowland Streaked Tenrec 3. Microgale cf. longicaudata - Lesser Long-tailed Shrew Tenrec 4. Microgale cowani - Cowan’s Shrew Tenrec 5. Microgale mergulus - Web-footed Tenrec 6. Nesogale cf. talazaci - Talazac’s Shrew Tenrec 7. Nesogale dobsoni - Dobson’s Shrew Tenrec 8. Setifer setosus - Greater Hedgehog Tenrec 9. Tenrec ecaudatus - Tailless Tenrec ARTIODACTYLA (127 genera, 308 species) ANTILOCAPRIDAE - pronghorns Antilocapra americana - Pronghorn BALAENIDAE - bowheads and right whales 1. Balaena mysticetus – Bowhead Whale 2. Eubalaena australis - Southern Right Whale 3. Eubalaena glacialis – North Atlantic Right Whale 4. Eubalaena japonica - North Pacific Right Whale BALAENOPTERIDAE -rorqual whales 1. Balaenoptera acutorostrata – Common Minke Whale 2. Balaenoptera borealis - Sei Whale 3. Balaenoptera brydei – Bryde’s Whale 4. Balaenoptera musculus - Blue Whale 5. Balaenoptera physalus - Fin Whale 6. Balaenoptera ricei - Rice’s Whale 7. Eschrichtius robustus - Gray Whale 8. Megaptera novaeangliae - Humpback Whale BOVIDAE (54 genera) - cattle, sheep, goats, and antelopes 1. Addax nasomaculatus - Addax 2. Aepyceros melampus - Common Impala 3. Aepyceros petersi - Black-faced Impala 4. Alcelaphus caama - Red Hartebeest 5. Alcelaphus cokii - Kongoni (Coke’s Hartebeest) 6. Alcelaphus lelwel - Lelwel Hartebeest 7. Alcelaphus swaynei - Swayne’s Hartebeest 8. Ammelaphus australis - Southern Lesser Kudu 9. Ammelaphus imberbis - Northern Lesser Kudu 10. Ammodorcas clarkei - Dibatag 11. Ammotragus lervia - Aoudad (Barbary Sheep) 12. -

Informational Issue of Eurasian Regional Association of Zoos and Aquariums

GOVERNMENT OF MOSCOW DEPARTMENT FOR CULTURE EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS & AQUARIUMS MOSCOW ZOO INFORMATIONAL ISSUE OF EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIUMS VOLUME № 28 MOSCOW 2009 GOVERNMENT OF MOSCOW DEPARTMENT FOR CULTURE EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS & AQUARIUMS MOSCOW ZOO INFORMATIONAL ISSUE OF EURASIAN REGIONAL ASSOCIATION OF ZOOS AND AQUARIUMS VOLUME № 28 _________________ MOSCOW - 2009 - Information Issue of Eurasian Regional Association of Zoos and Aquariums. Issue 28. – 2009. - 424 p. ISBN 978-5-904012-10-6 The current issue comprises information on EARAZA member zoos and other zoological institutions. The first part of the publication includes collection inventories and data on breeding in all zoological collections. The second part of the issue contains information on the meetings, workshops, trips and conferences which were held both in our country and abroad, as well as reports on the EARAZA activities. Chief executive editor Vladimir Spitsin General Director of Moscow Zoo Compiling Editors: Т. Andreeva M. Goretskaya N. Karpov V. Ostapenko V. Sheveleva T. Vershinina Translators: T. Arzhanova M. Proutkina A. Simonova УДК [597.6/599:639.1.04]:59.006 ISBN 978-5-904012-10-6 © 2009 Moscow Zoo Eurasian Regional Association of Zoos and Aquariums Dear Colleagues, (EARAZA) We offer you the 28th volume of the “Informational Issue of the Eurasian Regional Association of Zoos and Aquariums”. It has been prepared by the EARAZA Zoo 123242 Russia, Moscow, Bolshaya Gruzinskaya 1. Informational Center (ZIC), based on the results of the analysis of the data provided by Telephone/fax: (499) 255-63-64 the zoological institutions of the region. E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. -

1 Classification of Nonhuman Primates

BLBS036-Voevodin April 8, 2009 13:57 Part I: Introduction to Primatology and Virology COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL BLBS036-Voevodin April 8, 2009 13:57 BLBS036-Voevodin April 8, 2009 13:57 1 Classification of Nonhuman Primates 1.1 Introduction that the animals colloquially known as monkeys and 1.2 Classification and nomenclature of primates apes are primates. From the zoological standpoint, hu- 1.2.1 Higher primate taxa (suborder, infraorder, mans are also apes, although the use of this term is parvorder, superfamily) usually restricted to chimpanzees, gorillas, orangutans, 1.2.2 Molecular taxonomy and molecular and gibbons. identification of nonhuman primates 1.3 Old World monkeys 1.2. CLASSIFICATION AND NOMENCLATURE 1.3.1 Guenons and allies OF PRIMATES 1.3.1.1 African green monkeys The classification of primates, as with any zoological 1.3.1.2 Other guenons classification, is a hierarchical system of taxa (singu- 1.3.2 Baboons and allies lar form—taxon). The primate taxa are ranked in the 1.3.2.1 Baboons and geladas following descending order: 1.3.2.2 Mandrills and drills 1.3.2.3 Mangabeys Order 1.3.3 Macaques Suborder 1.3.4 Colobines Infraorder 1.4 Apes Parvorder 1.4.1 Lesser apes (gibbons and siamangs) Superfamily 1.4.2 Great apes (chimpanzees, gorillas, and Family orangutans) Subfamily 1.5 New World monkeys Tribe 1.5.1 Marmosets and tamarins Genus 1.5.2 Capuchins, owl, and squirrel monkeys Species 1.5.3 Howlers, muriquis, spider, and woolly Subspecies monkeys Species is the “elementary unit” of biodiversity. -

List-Primates-674J.Pdf

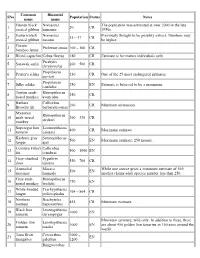

Common Binomial SNo Population Status Notes name name Hainan black Nomascus The population was estimated at over 2000 in the late 1 20 CR crested gibbon hainanus 1950s. Eastern black Nomascus Previously thought to be possibly extinct. Numbers may 2 35 – 37 CR crested gibbon nasutus be higher. Greater 3 Prolemur simus 100 – 160 CR bamboo lemur 4 Blond capuchin Cebus flavius 180 CR Estimate is for mature individuals only. Presbytis 5 Sarawak surili 200 – 500 CR chrysomelas Propithecus 6 Perrier's sifaka 230 CR One of the 25 most endangered primates. perrieri Propithecus 7 Silky sifaka 250 EN Estimate is believed to be a maximum. candidus Tonkin snub- Rhinopithecus 8 250 CR nosed monkey avunculus Barbara Callicebus 9 260 CR Minimum estimation. Brown's titi barbarabrownae Myanmar Rhinopithecus 10 snub-nosed 260 – 330 CR strykeri monkey Superagui lion Leontopithecus 11 400 CR Maximum estimate. tamarin caissara Kashmir gray Semnopithecus 12 500 EN Maximum estimate; 250 mature. langur ajax Coimbra Filho's Callicebus 13 500 – 1000 EN titi coimbrai Gray-shanked Pygathrix 14 550 – 700 CR douc cinerea Arunachal Macaca While one source gives a minimum estimate of 569, 15 569 EN macaque munzala another claims adult species number less than 250. Gray snub- Rhinopithecus 16 750 EN nosed monkey brelichi White-headed Trachypithecus 17 764 – 864 CR langur poliocephalus Northern Brachyteles 18 855 CR Minimum estimate. muriqui hypoxanthus Black lion Leontopithecus 19 1000 EN tamarin chrysopygus Minimum estimate; wild only. In addition to these, there Golden lion Leontopithecus 20 1000 EN are about 450 golden lion tamarins in 150 zoos around the tamarin rosalia world.