Japan: an Attempt at Interpretation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Taking Care of the Dead in Japan, a Personal View from an European Perspective Natacha Aveline

Taking care of the dead in Japan, a personal view from an European perspective Natacha Aveline To cite this version: Natacha Aveline. Taking care of the dead in Japan, a personal view from an European perspective. Chiiki kaihatsu, 2013, pp.1-5. halshs-00939869 HAL Id: halshs-00939869 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00939869 Submitted on 31 Jan 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Taking care of the dead in Japan, a personal view from an European perspective Natacha Aveline-Dubach Translation of the paper : N. Aveline-Dubach (2013) « Nihon no sôsôbijinesu to shisha no kûkan, Yoroppajin no me kara mite », Chiiki Kaihatsu (Regional Development) Chiba University Press, 8, pp 1-5. I came across the funeral issue in Japan in early 1990s. I was doing my PhD on the ‘land bubble’ in Tokyo, and I had the opportunity to visit one of the first —if not the first – large- scale urban renewal project involving the reconstruction of a Buddhist temple and its adjacent cemetery, the Jofuji temple 浄風寺 nearby the high-rise building district of West Shinjuku. The old outdoor cemetery of the Buddhist community had just been moved into the upper floors of the new multistory temple. -

2019 Autumn JAPAN

2019 Autumn JAPAN Eikando Zenrin-ji Temple P.10 ▶ Buffet P.23 ▶ Biei Blue Pond - Autumn Leaf Season P. 6 ▶ Kuju Flower Park P.13 ▶ Kegon Falls P.22 ▶ Hitachi Seaside Park P. 4 ▶ Maple Tree Tunnel 写真提供:叡山電車 P.10 ▶ Dinner (image) P.23▶ 鶴ヶ城(麟閣) Shirakawago 写真提供:岐阜県白川村役場 P. 8・9 ▶ 写真提供:(公財)福島県観光物産交流協会 P. 7 ▶ Sunrise Tours Product Categories Information Regarding All Tours Regarding Deadlines for Reservations Bus Company Please refer to “RSV. UNTIL” on each tour page. This will be the last day of application when the tour is decided Bus company used will be one of the following. to be as scheduled. If the deadline falls during Dec. 27th to Jan. 4th, the deadline will become Dec. 26th. P12 - 13 Kyushu Sanko Bus Co. Ltd., Sanko Bus Co. Ltd., Nishitetsu Kanko Bus Terms of Tour Conduction Co. Ltd., Fukuoka Nishitetsu Taxi Co. Ltd. Tours will not be conducted if the minimum number of participants indicated for each tour is not reached by a set date. The minimum P8 - 9, 24 must be reached 4 days prior to departure for one-day tours, and 20 days prior to departure for tours including accommodation. Meitetsu Kanko Bus Co. Ltd., Gifu Bus Co. Ltd., Meihan Kintetsu Bus Symbols Co. Ltd., or Shachi Bus Co. Ltd., P3 - 5, 8, 10 - 11, 14 - 17, 20 Place of Departure Fuji Kyuko Kanko Co. Ltd., Fuji Express Co. Ltd., KM Kanko Bus Co. From Tokyo Ltd., Hato Bus Co. Ltd., Tokyo Yasaka Sightseeing Bus Co. Ltd., Heisei Enterprise Co. Ltd., Amore Kotsu Ltd., Tokyo Bus Co. -

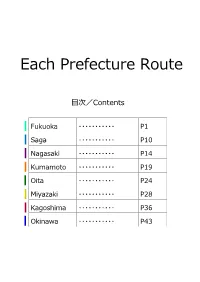

Each Prefecture Route

Each Prefecture Route 目次/Contents Fukuoka ・・・・・・・・・・・ P1 Saga ・・・・・・・・・・・ P10 Nagasaki ・・・・・・・・・・・ P14 Kumamoto ・・・・・・・・・・・ P19 Oita ・・・・・・・・・・・ P24 Miyazaki ・・・・・・・・・・・ P28 Kagoshima ・・・・・・・・・・・ P36 Okinawa ・・・・・・・・・・・ P43 福岡県/Fukuoka 福岡県ルート① 福岡の食と自然を巡る旅~インスタ映えする自然の名所と福岡の名産を巡る~(1 泊 2 日) Fukuoka Route① Around tour Local foods and Nature of Fukuoka ~Around tour Local speciality and Instagrammable nature sightseeing spot~ (1night 2days) ■博多駅→(地下鉄・JR 筑肥線/約 40 分)→筑前前原駅→(タクシー/約 30 分) □Hakata sta.→(Subway・JR Chikuhi line/about 40min.)→Chikuzenmaebaru sta.→(Taxi/about 30min.) 【糸島市/Itoshima city】 ・桜井二見ヶ浦/Sakurai-futamigaura (Scenic spot) ■(タクシー/約 30 分)→筑前前原駅→(地下鉄/約 20 分)→下山門駅→(徒歩/約 15 分) □(Taxi/about 30min.)→Chikuzenmaebaru sta.→(Subway/about 20min.)→Shimoyamato sta.→(About 15min. on foot) 【福岡市/Fukuoka city】 ・生の松原・元寇防塁跡/Ikino-matsubara・Genkou bouruiato ruins (Stone wall) ■(徒歩/約 15 分)→下山門駅→(JR 筑肥線/約 5 分)→姪浜駅→(西鉄バス/約 15 分)→能古渡船場→(市営渡船/約 15 分)→ 能古島→(西鉄バス/約 15 分)→アイランドパーク 1 □(About 15min. on foot)→Shimoyamato sta.→(JR Chikuhi line/about 5min.)→Meinohama sta.→ (Nishitetsu bus/about 15min.)→Nokotosenba→(Ferry/about 15min.)→Nokonoshima→(Nishitetsu bus/about 15min.)→ Island park 【福岡市/Fukuoka city】 ・能古島アイランドパーク/Nokonoshima island Park ■アイランドパーク→(西鉄バス/約 15 分)→能古島→(市営渡船/約 15 分)→能古渡船場→(西鉄バス/約 30 分)→天神 □Island park→(Nishitetsu bus/about 15min.)→Nokonoshima→(Ferry/about 15min.)→Nokotosenba→ (Nishitetsu bus/about 30min.)→Tenjin 【天神・中州/Tenjin・Nakasu】 ・屋台/Yatai (Food stall) (宿泊/Accommodation)福岡市/Fukuoka city ■博多駅→(徒歩/約 5 分)→博多バスターミナル→(西鉄バス/約 80 分)→甘木駅→(甘木観光バス/約 20 分)→秋月→(徒歩/約 15 分) □Hakata sta.→(About 5min. on foot)→Hakata B.T.→(Nishitetsu bus/about 80min)→Amagi sta.→ (Amagi kanko bus/about 20min.)→Akizuki→(About 15min. -

Japan: an Attempt at Interpretation

Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation Lafcadio Hearn Project Gutenberg's Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation, by Lafcadio Hearn #3 in our series by Lafcadio Hearn Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: Japan: An Attempt at Interpretation Author: Lafcadio Hearn Release Date: June, 2004 [EBook #5979] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on October 5, 2002] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK JAPAN *** [Transcriber's Note: Page numbers are retained in square brackets.] JAPAN AN ATTEMPT AT INTERPRETATION BY LAFCADIO HEARN 1904 Contents CHAPTER PAGE I. DIFFICULTIES.........................1 II. STRANGENESS AND CHARM................5 III. THE ANCIENT CULT....................21 IV. THE RELIGION OF THE HOME............33 V. -

A Japanese View of “The Other World” Reflected in the Movie “Departures

13. A Japanese view of the Other World reflected in the movie “Okuribito (Departures)” Keiko Tanita Introduction Religion is the field of human activities most closely related to the issue of death. Japan is considered to be a Buddhist country where 96 million people support Buddhism with more than 75 thousands temples and 300 thousands Buddha images, according to the Cultural Affaires Agency in 2009. Even those who have no particular faith at home would say they are Buddhist when asked during their stay in other countries where religion is an important issue. Certainly, a great part of our cultural tradition is that of Buddhism, which was introduced into Japan in mid-6th century. Since then, Buddhism spread first among the aristocrats, then down to the common people in 13th century, and in the process it developed a synthesis of the traditions of the native Shintoism. Shintoism is a religion of the ancient nature and ancestor worship, not exactly the same as the present-day Shintoism which was institutionalized in the late 19th century in the course of modernization of Japan. Presently, we have many Buddhist rituals especially related to death and dying; funeral, death anniversaries, equinoctial services, the Bon Festival similar to Christian All Souls Day, etc. and most of them are originally of Japanese origin. Needless to say, Japanese Buddhism is not same as that first born in India, since it is natural for all religions to be influenced by the cultures specific to the countries/regions where they develop. Japanese Buddhism, which came from India through the Northern route of Tibet and China developed into what is called Mahayana Buddhism which is quite different from the conservative Theravada traditions found in Thai, Burmese, and Sri Lankan Buddhism, which spread through the Southern route. -

Ecology, Behavior and Conservation of the Japanese Mamushi Snake, Gloydius Blomhoffii: Variation in Compromised and Uncompromised Populations

ECOLOGY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE JAPANESE MAMUSHI SNAKE, GLOYDIUS BLOMHOFFII: VARIATION IN COMPROMISED AND UNCOMPROMISED POPULATIONS By KIYOSHI SASAKI Bachelor of Arts/Science in Zoology Oklahoma State University Stillwater, OK 1999 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2006 ECOLOGY, BEHAVIOR AND CONSERVATION OF THE JAPANESE MAMUSHI SNAKE, GLOYDIUS BLOMHOFFII: VARIATION IN COMPROMISED AND UNCOMPROMISED POPULATIONS Dissertation Approved: Stanley F. Fox Dissertation Adviser Anthony A. Echelle Michael W. Palmer Ronald A. Van Den Bussche A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I sincerely thank the following people for their significant contribution in my pursuit of a Ph.D. degree. I could never have completed this work without their help. Dr. David Duvall, my former mentor, helped in various ways until the very end of his career at Oklahoma State University. This study was originally developed as an undergraduate research project under Dr. Duvall. Subsequently, he accepted me as his graduate student and helped me expand the project to this Ph.D. research. He gave me much key advice and conceptual ideas for this study. His encouragement helped me to get through several difficult times in my pursuit of a Ph.D. degree. He also gave me several books as a gift and as an encouragement to complete the degree. Dr. Stanley Fox kindly accepted to serve as my major adviser after Dr. Duvall’s departure from Oklahoma State University and involved himself and contributed substantially to this work, including analysis and editing. -

Baffelli, Erica, and Ian Reader. "Transcending Death: the Birth And

Baffelli, Erica, and Ian Reader. "Transcending Death: The Birth and Spiritual Messages of the Second Buddha." Dynamism and the Ageing of a Japanese ‘New’ Religion: Transformations and the Founder. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2019. 125–156. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 6 Oct. 2021. <http://dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781350086548.ch-005>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 6 October 2021, 16:51 UTC. Copyright © Erica Baffelli and Ian Reader 2019. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 1 25 5 Transcending Death: Th e Birth and Spiritual Messages of the Second Buddha Introduction: dealing with the death of a founder Th e death of Kiriyama in August 2016 represented a major rite of passage for Agonsh ū . It was already facing a dilemma that confronts movements when their charismatic founder ages and appears less able to perform the roles or show the dynamism they previously did. Even if they can still make use of the founder’s presence, as Agonsh ū did in Kiriyama’s later years when, although visibly weak, he continued to appear at ritual events, the loss of visible vitality may cause problems. Death presents an even greater dilemma. What happens when the fi gure whose insights and communications with spiritual realms provide the foundations of the movement’s truth claims is no longer physically present to provide a direct link with the spiritual realm? Once the founder dies, the movement has to deal both with the loss of physical presence and the problem of how to regard the deceased fi gure. -

Ghenko, the Mongol Invasion of Japan

1 GHENKO THE MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN HOJO TOKIMUNE. GHENKO THE MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN BY NAKABA YAMADA, B.A. (Cantab.) WITH AN INTRODUCTION BY LORD ARMSTRONG WITH ILLUSTRATIONS AND MAPS LONDON SMITH, ELDER & CO., 15 WATERLOO PLACE 1916 [All rights reserved] *L\ 3 Y PREFACE evening in the summer before last, I ONEwas sitting in the reading-room of my College in Cambridge, when a small " " book entitled Westward Ho ! caught my eye. I was greatly attracted by its contents. In the mellowing light of the sun, I perused the book page after page, until my attention was diverted by the dining-bell from the hall. Ending my perusal, however, I stood a while with the pleasant memory of what I had read. One of my friends told me at table that that book was one of the great works of Charles Kingsley, and well worth reading. Having ob- tained a new copy, I finished the reading before long. It was from this reading that I acquired the idea of writing this book. My first intention was " to describe the historical event of the Mongol " " Invasion of Japan in such a novel as Westward " Ho ! But I have found it better to write an authentic, straightforward history rather than to use the medium of fiction. For the facts, which v 348467 PREFACE would be used as the basis of an historical novel, are not known to our Western friends as a whole, as the Chino-Japanese war or the Russo- war has been this is Japanese ; probably owing both to the remoteness of the events and the difficulties of research work, in a field so far removed in time and place. -

A POPULAR DICTIONARY of Shinto

A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto A POPULAR DICTIONARY OF Shinto BRIAN BOCKING Curzon First published by Curzon Press 15 The Quadrant, Richmond Surrey, TW9 1BP This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to http://www.ebookstore.tandf.co.uk/.” Copyright © 1995 by Brian Bocking Revised edition 1997 Cover photograph by Sharon Hoogstraten Cover design by Kim Bartko All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 0-203-98627-X Master e-book ISBN ISBN 0-7007-1051-5 (Print Edition) To Shelagh INTRODUCTION How to use this dictionary A Popular Dictionary of Shintō lists in alphabetical order more than a thousand terms relating to Shintō. Almost all are Japanese terms. The dictionary can be used in the ordinary way if the Shintō term you want to look up is already in Japanese (e.g. kami rather than ‘deity’) and has a main entry in the dictionary. If, as is very likely, the concept or word you want is in English such as ‘pollution’, ‘children’, ‘shrine’, etc., or perhaps a place-name like ‘Kyōto’ or ‘Akita’ which does not have a main entry, then consult the comprehensive Thematic Index of English and Japanese terms at the end of the Dictionary first. -

Chapter One Introduction

CHAPTER ONE INTRODUCTION 1.1.Background of Study Japan has so many traditions of folklore that had inherited for generation whether in story form or in tradition form. With some creativity and existing technology that they had, some Japanese filmmaker has succeeded by making some Japanese folklore into more interesting form and well known by people whether inside Japan or outside Japan. According to Kitayama “Folklore is a stories shared by folk people from the past and these stories are similar to myths, except that they are related more to human matters than to supernatural beings” (Kitayama 2005: 85) By this quotation the writer argue that folklore is cultural product which is produced by people in the past and it is contained of myth and usually, the society will connect the folklore to supernatural even more to human matters. As emphasized by Lindahl, Although many people regard a “folktale” as a fictional form, I use the term here to apply to any traditional tale, whether its tellers consider it true, or false, or both. Thus, the scope of the tale extends far beyond fiction to encompass belief tales, personal experience stories, and accounts of major historical events (Lindahl, 2004: 200). Based on the quotation above, the writer argues that folklore acknowledges the practice of labeling narratives based on the element of belief, he also realizes the inherent story within each and the tendency of storytellers to use a little fiction and a little nonfiction in crafting their stories. Lindahl uses this terminology to put the focus on the storytellers themselves and help the reader to recognize the relationship between tale and teller. -

Arquitetura E Tática Militar: Fortalezas Japonesas Dos Séculos XVI-XVII

1 Universidade de Brasília Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo Programa de Pós-graduação (PPG-FAU) Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo Arquitetura e tática militar: Fortalezas japonesas dos séculos XVI-XVII Dissertação de Mestrado Brasília, 2011 2 3 Joanes da Silva Rocha Arquitetura e tática militar: Fortalezas japonesas dos séculos XVI-XVII Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-graduação da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial para obtenção do grau de Mestre em Arquitetura e Urbanismo. Orientadora: Prof.ª Dr.ª Sylvia Ficher. Brasília, 2011 4 5 Joanes da Silva Rocha Arquitetura e tática militar: Fortalezas japonesas dos séculos XVI-XVII Esta dissertação foi julgada e aprovada no dia 9 de fevereiro de 2011 para a obtenção do grau de Mestre em Arquitetura e Urbanismo no Programa de Pós-graduação da Universidade de Brasília (PPG-FAU-UnB) BANCA EXAMINADORA Prof.ª Dr.ª Sylvia Ficher (Orientadora) Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo FAU/UnB Prof. Dr. Pedro Paulo Palazzo Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo FAU/UnB Prof. Dr. José Galbinski Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo UniCEUB Prof.ª Dr.ª Maria Fernanda Derntl Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo FAU/UnB Suplente 6 7 Gratidão aos meus pais Joaquim e Nelci pelo constante apoio e dedicação; Ao carinho de minha irmã Jeane; Aos professores, especialmente à Sylvia Ficher e Pedro Paulo, que guiaram-me neste jornada de pesquisa; Obrigado Dionisio França, que de Nagoya muito me auxiliou e à Kamila, parentes e amigos que me incentivaram. -

Where the Action Is Sites of Contemporary Soto Buddhism

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 31/2:357-388 © 2004 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture M ark R o w e Where the Action Is Sites of Contemporary Soto Buddhism This article considers reactions at various levels of the Soto sect to the prob lems of funerary Buddhism. There is a widening gap, not only between the necessities of mortuary practice at local temples (both rural and urban) and the doctrine of no-self ostensibly embodied in the foundational texts of Dogen and Keizan, but also within the very organizational structures of the Soto sect itself. From its official publications and regional conferences to innovative strategies being developed at individual temples, I argue that, far from being a unified body, Soto Buddhism speaks with an array of competing and often contradictory voices. The diversity of Soto responses to the “mortuary prob- lem” reveals intriguing disconnects between the research arm of the sect, those responsible for training priests, and the daily realities of local temples. k e y w o r d s : Soto Zen - genba - mortuary rites - ordination ceremony - sosai mondai Mark Rowe is currently finishing his PhD in the Religion Department at Princeton University. His dissertation explores the impact of changing Japanese burial practices on contemporary Japanese Bud dhism. 357 T he “funeral problem” (sosai mondai 葬祭問題)is a catchall term for a broad range of doctrinal, historical, social, institutional, and economic issues confronting the traditional sects of Japanese Buddhism. While these issues are clearly interrelated, this “problem” means very different things to different groups, even to those within the same organization.1 This article will explore the complexity of these issues by considering contrasting conceptions of the sosai mondai at two sites” of contemporary Soto Zen: within the activities of sectarian intellectuals and at a popular Tokyo temple.